display screens for memory impared in stock

Task Oriented: Most people always have something to do. Even if they don"t, they create something to keep their hands and brain busy. People with Alzheimer"s relive their former lives and leave their home believing they are going to a job or shopping.

Pain, discomfort and agitation: Emotions can be reason to wander. They are not happy in their present situation so if they move to another location maybe those symptoms will not come with them. But in actuality, they are wandering.

Loss of Memory: When people become disoriented due to their present thoughts disappearing, their reality being blurred or seeking places that were once familiar to them, they wander looking to go back to those comforting and safe places. They are searching for their past.

2) Prepare the home or facility by using products that can lessen the possibility of an occurrence and its effect on all involved. Make it harder for them to wander and if they do, make it safer.

Fire Rated Door Mural that is approved for commercial facilities. It consists of a picture of a bookshelf that is so real, you have to touch it to know that it is a mural! The disoriented person no longer sees a door to go through. This is great for hiding utility closets or basement doors.

4) GPS devices are the newest technology for wandering. The Alzheimer"s Store distributes devices that are locked on the wanderer"s wrist, such as the

medical alert bracelet is an ID bracelet with the international scanning icon. All emergency responders carry scanning devices. It is also equipped with a url address with the wanderer"s personal pin number. This pin number allows the caregiver/responder access to all medical records or contact information that has been preloaded into it from a computer.

Many of our alert products are monitored by an emergency response center with personnel who are experienced and have specific training to respond to those with Alzheimer’s, Dementia and Memory Loss. This type of experience is crucial in a time of emergency.

I can’t thank you enough for working me to get the phone up & running for my mom. She’s starting to adjust to using it. This phone will help her as she gets flustered with all the options even on a basic cell phone.

I am so grateful for this phone & the wonderful support staff that helped me with my questions & missteps. Tried out the phone with family members & are anxious to give it to her on Monday, her 92nd birthday. This will be a godsend for her to be able to communicate with her family during these difficult times. Usually there are only 5 stars but would give 10! Thank you for making this a very bright moment. Thank you again.

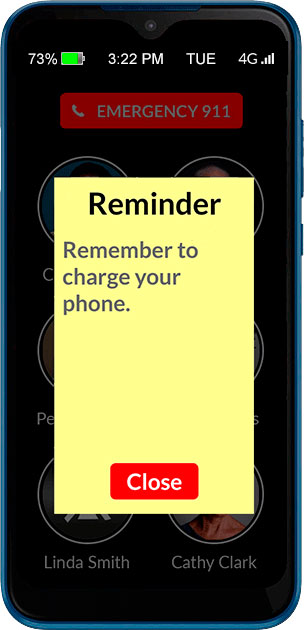

I have been looking for a phone that would not confuse my Mother with her dementia. I have not found a phone that would work for her until I found this one. Having the ability to set up and control the phone from the caregiver portal has greatly reduced the time I have to spend dealing with phone issues. My Mother lets me know if she needs to add a number to her list and I can do the from anywhere without having to physically change it on her phone. I also like being able to check the battery level from the portal adn let her know if she needs to charger her phone if she forgets. No more assuming the phone is just dead. The GPS feature also gives me peace of mind to know were she is or if her phone was left somewhere. This is a great solution if you are looking for a phone for your family member with dementia.

I am so very thankful for this phone. It has given my father a sense of freedom again. His confidence in using the phone is phenomenal and we haven’t been able to say that in a while. I am wondering if there is a case that can be recommended that has a cover for the front that will stop accidental calls. PLEASE LOOK AT THIS PHONE FOR YOUR LOVED ONE, YOU WON’T REGRET IT.

I purchased this phone for my mom who has dementia and was having great difficulty using even her simple flip phone. It is very easy to use and wonderful that I can manage the phone from the portal. I would rate “5” except 1) I assume there is no way to disable the 911 function due to legal issues, but it would be nice if I could since she is in a nursing home and help is always nearby; 2) would be nice to get rid of the message that says “individual’s voicemail has not been set up” since there is no voicemail option (I get calls from my mother’s family asking why she has no voicemail); 3) would be nice to be able to increase the number of rings. It only rings four times and it usually takes her longer than that to get across her room to answer since she doesn’t carry the phone around with her. All in all, though, very happy with this purchase.

As for 2) the voicemail message and 2) the number of rings – these are control day the wireless provider. The number of rings / ring duration can bu adjusted by some of the carriers. Please contact the carrier and request it to be changed.

This phone is very nice to look at and easy to use. I love that we can limit the calls that my mom receives. She was always so confused by the spam calls about the extended warranty for her car. It’s great that she doesn’t get those anymore. It’s also really nice that she can see photos of my sisters and me to decide who she wants to call.

However, there are a couple of things I do not like. One, the volume is fixed, and it is too loud for certain situations. Secondly, there is no way to track missed calls, or voice mail.

This phone solved our conundrum with needing a simple phone for our older guy who now feels reconnected without the barrage of incomprehensible scammers. The tech support and customer service is responsive, efficient and superb.

I just wanted to say thank you for this product. My mom, who has dementia, broke her hip, got COVID while in the hospital and ended up recovering from both in isolation in a nursing facility. She has been struggling to understand what is happening to her and not being able to be there with her has been a challenge for all of us. This phone has helped her tremendously. She had forgotten how to use a cell phone a long time ago but she can use this phone and it has lifted her spirits to stay in touch and she likes looking at our pictures. It’s such a well designed product and the customer support you offer is very appreciated as well. The staff at the Verizon store wrote down the information because they said they get requests for senior-friendly phones all the time and they don’t sell anything like this phone. The therapy staff at the nursing home commented that they love the phone as well and will be recommending it to other families in the facility.

This phone has been a godsend to me as the caretaker of my mother from three states away. I love how I can manage the phone via the portal. There are so many things I love about this phone and its ease of use for my mother. Other reviews talked about the default ringtone volume being very loud and unable to change. The ringtone volume was super loud! I called RazMobility Support and they walked me through how to lower the ring volume (but you can only do it when having the phone physically with you and they walk you through all of the steps). I’m sure there are other changes RazMobility support can help you with. Just call them and ask, “Can _____ be adjusted on the phone?” They have been super helpful. I love how simple the portal is to manage and how I can see the battery life, and GPS location of my mother’s phone. The MintMobile cell service did not do too well in my mother’s nursing home, but it was easy to switch out the SIM cards to another carrier. But make sure you purchase the more expensive Raz phone so you can easily switch carriers if you need to. I would have stayed with MintMobile if the reception was better as their website is super easy to navigate. So this review doesn’t go on forever, I’ll focus on some features I would like to see in the future: recent call list, ability to adjust the ringtone volume, voice volume from portal. One glitch I’ve found is that when my mother presses the “Hang Up” button too long, she accidentally calls the contacts listed in the #5 & 6 spots. To avoid her accidentally calling someone a lot, I added my contact info into slots 5 & 6. So if it happens, she is just calling me. We also bought the wireless charger (which comes with the protective phone case). That way my mom does not have to struggle to plug in the regular phone charger. The wireless charger charges super slow to avoid wearing out the battery. This phone is awesome. Raz, if you created an affiliate program, I think you could get the word out even more about this phone. I would be a huge cheerleader of the phone!

I purchased this phone for my Dad who we just moved into a nursing home due to dementia. He became unable to remember how to work his old cell phone or the regular telephone. The RAZ has been a Godsend. It’s so easy for him to use and he is absolutely thrilled to be re-connected with his family. I had a little trouble activating it, ( a senior citizen setting up a phone for a senior citizen…what could go wrong???). But I called customer service and the rep that helped me was amazing. Patient and knowledgable and even emailed me pictures of what things should look like along the way. She made sure I knew how to add names and pictures to the phone and even offered to do it for me if I emailed her the pictures. I’ve called a few times with questions and I reach a human being quickly and they always know the answer to my questions. Customer service of the highest caliber. So far the only downside is that when the phone is in the case the volume of the ringtone is very low and my Dad doesn’t always hear it. I’ve called customer service and they told me that I have to be near the phone to adjust the volume, so the next time I am there I will give them a call. The RAZ is the absolute perfect cell phone for any senior but especially one who has impaired mental capabilities.

My 92 year old father loves this phone. I love not worrying that someone is scamming him over the phone. He loves showing it off to his friends at the retirement community. I love not spending hours trying to talk him through getting him back on his phone. He loves not calling the wrong person because he touched the wrong line in his contacts. I love updating new phone numbers for his contacts without having to have his phone in hand. For us it’s a win/win/win

My Dad doesn’t have dementia but is 87. We got the Raz phone and it’s like a long, cool drink of water. We tried Jitterbug and Jethro “senior friendly” phones and they were a JOKE. Raz is the first truly SIMPLE phone – no menus, God bless them, and remotely configurable. The only thing I would criticize, and I hope Raz is listening… About once or twice a day, the Raz phone makes an outgoing call while in my Dad’s pants pocket. I have witnessed this first-hand. He’s puttering around the kitchen, not bending over, not with his hands in his pocket, and his phone calls me. If he were allowed to “turn off” the screen before he puts the phone in his pocket, I believe the problem would be fixed. We did try a belt holster, but with his posture, his belt is too close to his armpits and it takes so long to get the phone out of the holster that the phone stops ringing before he can answer.

I purchased this phone for my brother who has rapid arm and hand tremors due to Parkinson’s Disease. He also has early Dementia. He is not tech savvy at all. The Raz phone is truly a blessing to him and my family not only because it’s simple and easy to use, but it eliminates the clutter he would have to navigate through using the traditional smart phone. He is proud that he has a device that is fully simplistic and streamlined to his need, but also instills his dignity just by the phone’s impressive appearance. Raz mobility technical support is Fantastic! I have dismissed products from other companies just on the premise of customer support alone, regardless of the quality of product. I was helped by Alex at Raz Tech support. He was extremely knowledgeable, methodical, courteous, and above all, patient. I enjoyed one of the best customer experiences I have had in many months. Kudos to Alex.

I found the RAZ Phone easy to get set up and it works as advertised. This will be a big help as my wife has memory problems. Now I feel comfortable being away from her for a while. Thanks.

Great phone for those with dementia. Easy to set up from the caregiver portal. Customer Service is great. An improvement would have the phone shut off automatically if not being used since the battery goes down and the phone has to be charged daily.

I recently returned my mother’s Memory Cell Phone because someone at her care facility had inadvertently exited the app and did a factory reset. Within a week, I had the phone back with the app reinstalled. Not only that, you installed the new version which has great new options AND sent a complimentary wireless charging platform because she had damaged the charger port trying to put the charger in the wrong way. That is customer service above and beyond.

This is close to being the perfect phone for those with dementia and those of us who care for them. It is so very well thought-out, anticipating all the problems. For the first time in months, my husband can call me when he’s feeling anxious or worried from his memory care facility. It has been such a relief for both of us.

The Memory Phone has been a wonderful solution to our parent’s dementia challenges. What a relief to have the confidence that they can call when they want and not be discouraged by the complexity of a smart phone.

The RAZ is a great phone. Customer service is outstanding. I bought this for my Mom who has Alzheimer’s. Unfortunately we waited a little to long to make the change. She was not able to make the adjustment to the phone and I had to return it. With that being said, this is a wonderful cell phone, I am super impressed with how it works and the options for the caregiver from the portal. I will be telling anyone I know who needs this service. We did the T-Mobile version and had zero problems. Just put the SIM card in and it worked perfectly. Thanks for a great product!

RAZ MEMORY phone is exceptional for my father in law age 94. He has some age related dementia combined with macular degeneration. Especially helpful are the auto answer to speaker phone options. He is able to call us usig the limited photo buttons. And, NO MORE JUNK CALLS. Wish we were aware of this earlier. We are showing it off at his new Assisted Living Community. We also love the optional charging cradle which is home for the phone most of the time.

This phone is fabulous for my mom who has dementia. We tried several ‘easy’ and ‘senior’ phones before finding this one. This is the only one she’s been able to use reliably. Being able to control the phone settings from my phone is great; no more deleted contacts or turning her phone off then wondering why it wasn’t working. The phone works well on the T-Mobile network. I had to contact customer service and was shocked to be connected to a person right away. He immediately identified the issue and walked me though how to fix it. The call lasted maybe 5 minutes and there have been zero issues since. I wish we’d found this phone a couple years ago. It would have saved both mom and family members a lot of frustration.

Easy for my non-tech husband to use. We set it to auto answer and speaker phone, so he doesn’t even need to pick it up. Makes us feel more secure for those times when I need to leave him alone for short periods.

This unique High Resolution GREEK LANGUAGE digital day clock clearly spells out the full DAY of the Week, MONTH and DATE in large, BOLD LETTERS - with no confusing abbreviations. Many seniors suffering from memory loss due to dementia, stroke, Alzheimer"s or just advancing years, often have difficulty processing abbreviated words.

The Clock is Preset to GREEK. Ideal clock for people of all ages! Great for Home, Office or even Classroom use. The clock can also be set to display in ENGLISH. The words Dementia, Alzheimer"s or Memory Loss are ‘not’ printed on the clock itself, so it makes a great gift for those special loved ones, especially Grandparents. The clock’s internal menu is in GREEK, and the instruction card is written in English.

The DATE FORMAT display can be switched from the EUROPEAN DATE FORMAT (Day/Month/Year) to display in the AMERICAN DATE FORMAT (Month/Day/Year) via the internal menu. The Display can also be easily set to 12 hour or 24 hour (Military Time). This clock is perfect for people with macular degeneration. It has a bright and clear display that can be seen from across the room. It"s bold, sharp & non-glare display is invaluable for the visually impaired and the elderly.

Overall Dimensions: 8.5" wide x 6.75" high x 1" deep (4.5" deep with Kickstand) 8" diagonal display screen. Can be used as a Desk clock or Wall clock. The clock requires an A/C adapter (US adapter included) to operate. Does not run on batteries. The clock is shipped with a removable thin plastic screen protector, to protect the screen during transit. One Year US warranty - void when used outside USA.

This unique High Resolution RUSSIAN LANGUAGE digital day clock clearly spells out the full DAY of the Week, MONTH and DATE in large, BOLD LETTERS - with no confusing abbreviations. Many seniors suffering from memory loss due to dementia, stroke, Alzheimer"s or just advancing years, often have difficulty processing abbreviated words.

The Clock is Preset to RUSSIAN. Ideal clock for people of all ages! Great for Home, Office or even Classroom use. The clock can also be set to display in ENGLISH. The words Dementia, Alzheimer"s or Memory Loss are ‘not’ printed on the clock itself, so it makes a great gift for those special loved ones, especially Grandparents. The clock’s internal menu is in RUSSIAN, and the instruction card is written in English.

The DATE FORMAT display can be switched from the EUROPEAN DATE FORMAT (Day/Month/Year) to display in the AMERICAN DATE FORMAT (Month/Day/Year) via the internal menu. The Display can also be easily set to 12 hour or 24 hour (Military Time). This clock is perfect for people with macular degeneration. It has a bright and clear display that can be seen from across the room. It"s bold, sharp & non-glare display is invaluable for the visually impaired and the elderly.

Overall Dimensions: 8.5" wide x 6.75" high x 1" deep (4.5" deep with Kickstand) 8" diagonal display screen. Can be used as a Desk clock or Wall clock. The clock requires an A/C adapter (US adapter included) to operate. Does not run on batteries. The clock is shipped with a removable thin plastic screen protector, to protect the screen during transit. One Year US warranty - void when used outside USA.

When the phone rings, two big buttons will appear. A green one that says “Answer” and a red one that says, “Hang up”. If the caller is a contact, a large picture and name of the caller will be displayed. A new feature called Auto-Answer can also be enabled. Incoming calls will be answered automatically, without pressing “Answer”.

No need to remember 911 digits. User can simply press, and hold dedicated 911 button. If your loved-one repetitively calls 911 for false or imagined emergencies, an optional Emergency Call Service is available to help screen 911 calls once the phone is activated and set up. This service has multiple plans all under $8/mo.

The volume rocker is disabled. For both regular and speakerphone calls. Volume is always on maximum and ideal for those who are hard of hearing. The ringtone and ringtone volume can be set via the caregiver portal to make sure a call is never missed.

The RAZ Memory Cell Phone can be limited to receiving calls. In advanced stages of memory loss, users may forget their contacts or forget that they made a call just minutes ago. The ability to limit calls to incoming calls only, addresses this challenge, while ensuring that the person can be reached by their loved ones and call 911 in case of an emergency.

The RAZ Memory Cell Phone has a long lasting 4,000 mAh battery. A low battery alert can also be sent to the caregiver via text message to be sure their loved-one is keeping their phone charged!

The list below shows the carriers supported by this phone. You can bring your own carrier as a new line or add the phone to a family plan. Make sure you get a strong signal from the carrier of your choice in your area to ensure optimal performance!

The PMIS is a quick and reliable screen for dementia that can be used in older adults with little or no education. It discriminated cognitively normal older adults from those with dementia regardless of age, sex, education, severity of dementia, or presence of depression. All participants completed the PMIS, which took approximately 4 minutes including the interference task. High interrater reliability was demonstrated between administration of PMIS by the clinician and the nurse. The high alternate-forms reliability supports use of different PMIS sets for repeated testing. Professionals and nonprofessionals successfully administered the PMIS in urban and rural clinic settings. The PMIS was administered on a computer screen and using cards. These findings support the feasibility of using the PMIS in various settings and by personnel with different levels of expertise.

Pictures are remembered better than words. The visual component of the PMIS involves deeper or additional layers of cognitive processing; enhancing learning and recall. Poor visual memory predicts dementia,

Table 2 shows sensitivity and specificity based on the sample and PPV and NPV at hypothetical dementia base rates that can guide choice of cut-scores. A sensitive PMIS cut-score can be used to monitor cognitive function in older adults and guide timing of follow-up visits, whereas a specific cut-score with high PPV can be used to avoid false-positive cases when recruiting candidates for clinical trials involving potentially toxic medications.

The initial step in evaluating older adults presenting with cognitive complaints is to detect or exclude dementia regardless of subtype. Because the PMIS is a cognitive screening test, individuals who fail it should be referred for definitive diagnostic assessment. Alternatively, individuals scoring in the normal range could be asked to return for a repeat screen at a longer interval.

Screening for dementia, much like screening for other diseases or chronic conditions, is a good way to detect the changes that can be signs of the onset of disease or other change in cognition. Memory screening and early detection provide:The ability to make lifestyle and other beneficial changes earlier in the disease process when they have the greatest potential for positive effect.

Time to connect with community-based information and supportive services prior to a potential crisis situation related to the needs of the person with dementia or the caregiver.

To enable people with dementia and their caregivers to benefit from memory screening and early detection, a community-based memory screening program was developed by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute using the Animal Naming Screen, the Mini-cog, and the AD8.

The Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools were selected after a pilot study in Portage County in 2009. The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute, the Aging and Disability Resource Center (ADRC) of Portage County, and DHS demonstrated the acceptability and effectiveness of using the Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens in a community setting. The Animal Naming screen is attached as Appendix C (PDF) and the Mini-cog as Appendix D (PDF)

Results from the pilot demonstrated ADRC customers’ high level of acceptance of screening. The offer of a memory screen was accepted by 243 out of 254 people, a 96% acceptance rate. This result contradicts the idea that people do not want to be screened for dementia. The tools were also effective in detecting cognitive issues. Of the 243 people who were screened, 150 (63%) had results that indicated they should follow up with their physician. This result may seem surprisingly high, but screens were only offered to individuals who expressed a concern about their memory, so those with cognitive issues self-selected into the study. Of those 150 people, 120 or 80% agreed to have the results sent to their physician.

The Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens were selected not only for their acceptability and effectiveness, but also because they are brief, easy to administer and score, and are sensitive to early cognitive changes. Some screens must be administered by physicians or psychologists and can take more than an hour. The minimum level of training required and the short length of time necessary to administer the screens was a critical component in their acceptance for use by ADRC staff.

The screens were also selected because they have documented utility as dementia screens and tap key skills likely to be affected in mild to moderate dementia. The Animal Naming screen involves retrieval from semantic memory and executive function, two areas of cognition that reliably decline in people with Alzheimer’s disease. In a study of memory clinic clients with a high base rate of dementia, the Animal Naming screen was shown to have 85% sensitivity and 88% specificity for differentiating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia from normal cognition. The Mini-cog screen tests memory as well as visuoconstruction and executive function, with studies showing sensitivity for dementia of 76% to 99% and specificity of 83% to 93% in analyses that excluded patients with mild cognitive impairment.

Memory screens are voluntary, so there will be individuals who decline to participate. On these occasions, if family caregivers are uncertain whether their concerns about the person they are caring for are valid, the AD8 screen can help determine whether a visit to the doctor is recommended. The AD8 (PDF) tool is available in both English and Spanish. This screen is intended to help the caregiver think through the changes they see in a family member, and may help them to realize it is time to take action. The screen can be provided to the family caregiver to complete on their own, or the questions can be asked by the screener in a private setting. The AD8 has sensitivity for dementia of greater than 84% and a specificity of greater than 80%.

In 2020, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool was added to the approved tools for use by dementia care specialists (DCS). This tool is not for use by ADRC staff other than the DCS. The intention behind the addition of the MoCA screen is to give DCS an additional tool for situations that are more complex. While the Mini-cog and the Animal Naming screens are more sensitive to earlier changes than other screens, they are limited to a few areas of cognition. The MoCA covers a wider variety of cognitive tasks and provides additional insight into possible cognitive impairment when the Animal Naming and Mini-cog results do not reflect the changes in cognition and behavior reported by the individual or their family.

New dementia care specialists should become very familiar with the Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools prior to adding the MoCA to their toolkit. There are some similarities and some differences between the activities of the Animal Naming and Mini-cog and those in MoCA. Learning all the screens at the same time can be confusing, so it is advised for new staff to focus on the Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens, as well as the AD8, prior to becoming certified to provide the MoCA screen. Training and certification for the MoCA, and the approved form, are available from the official MoCA website. There is a cost to the training and certification for the MoCA. The MoCA is not required to be provided as a part of this program but is available as a supplemental tool.

The primary intent of this memory screening protocol is to enable and enhance conversations about memory concerns. The screens are not diagnostic tools and do not make any determinations about mental status. The screens are similar to a blood pressure check, in that a high blood pressure reading does not mean an individual has cardiovascular disease, but is a signal to talk to a physician about the results. The screens can be a reason to bring up the topic of memory issues because they can be offered in the moment. A referral to the physician can be more meaningful if an objective tool verifies that an individual’s concerns with memory and cognition should be further assessed.

It is appropriate to offer a memory screen when one is requested, or when working with a customer who displays signs of possible memory loss or confusion. ADRC specialists are able to offer the screening program during a visit for another purpose, if time allows. It is preferable to address the concerns around memory at the time, rather than putting off the discussion for another appointment. Memory screening is always voluntary.

Staff members may feel uncomfortable offering a memory screen if they are not used to asking and answering questions about memory and dementia. It is important that staff who are offering the screens understand why screening is important and helpful to the customer. Practicing offering the screen to coworkers and family members can be a good way to become more comfortable. Staff must be trained to follow the guidance in this manual before performing memory screens with the public.

If other people are present for the screening, let them know they will need to remain quiet and not help the person answer the questions. Ensure the participant cannot easily view and copy a clock in the room.

Begin with Animal Naming. It is critical to read the instructions for each task on both screens exactly as they are written. Do not explain how the screen is scored prior to performing the screen, and only afterwards if the individual asks you to do so. To adhere to the fidelity of the tools, they must be performed exactly the same way every time to ensure the results are valid. Read the instructions to the participant: “Please name as many animals as you can think of as quickly as possible.” Be prepared for the person to start listing animals immediately or, if they do not, prompt them with “Go.”

Once the person begins to name animals, start the timer and record all the animals named within 60 seconds in the spaces provided on the worksheet. If the person is speaking quickly, write as much of the word as needed to remember what was said and fill in the remaining letters afterward. If the person falls silent, follow the prompting instructions. Once the Animal Naming screen is done, administer the Mini-cog, even if the score of the Animal Naming screen was very high. The two screens should always be used together.

The Memory Screening in the Community program is intended for the Animal Naming tools and the Mini-cog tool to be used in combination. In this non-clinical program, the standard Mini-cog tool available online has been adapted to work in concert with the Animal Naming Tools. Refer to Appendix D to access the form to record results.

Begin the Mini-cog by telling the participant, “I am going to say three words I want you to remember,” and repeat the three words listed on the worksheet. Be sure to read the instructions exactly as they are written. It is important to the fidelity of the screen to use the same three words every time the screen is performed. Give the participant three chances to repeat the words back. If the participant does not repeat the words, or does not repeat them correctly, the screener can repeat the words up to three times until the words are repeated correctly. If they are not correct after the third time, move on to the clock draw.

Provide a blank, standard, letter-size sheet of paper for the participant to draw on and a writing utensil. This can be the back of the Animal Naming worksheet or another blank sheet. Allow the participant time to adjust to the new task, pick up the writing utensil, and adjust the paper. Once the participant is settled, read the instructions for the clock draw exactly as they are written, pausing when indicated to allow the participant to complete the task. Move on from this task if the clock is not complete within three minutes.

There will be individuals that frequently request to be screened. If they express the desire for an alternate set of words used for the three-word recall portion, refer to the words listed in the Health Equity section for Hmong translation. The need for an alternative set of words was first identified in the need for the translation of the words into Hmong. they do not easily translate into that language, so an alternative set of words was identified for that purpose. That substitution can also be applied for individuals who request frequent screening.

The AD8 can be administered to the person with possible memory loss, but often individuals with dementia lose insight into their condition and are not reliable self-reporters. The questions on the screen can either be read aloud or a caregiver can fill out the form on their own. In situations where the person with possible memory loss is together with the caregiver, allowing the caregiver to fill out the questionnaire silently may be less upsetting for the person with possible memory loss than if the questions are asked aloud. The caregiver may also provide different answers if the person with possible memory loss is listening to the answers.

The MoCA tool, including training, certification, and the downloadable version of the paper tool can be found on the MoCA website. The MoCA is also available to be used digitally. Instructions for how the MoCA tool is scored are a part of the training and certification process.

The Memory Screening in the Community program was adapted in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic for use when screening was required to be completed virtually. The ability to provide screening virtually for dementia risk has been identified as an ongoing need. Please consult Section IV: Accessibility and Health Equity Considerations for a description of the adaptation for virtual access.

The use of the Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools in the Memory Screening in the Community Program is different than as a part of Wisconsin’s Long-Term Care Functional Screen (LTCFS). The purposes for the use of these tools in the Memory Screening in the Community Program are to enable a conversation and assist in determining whether speaking to a physician is advisable. The LTCFS uses the tools to represent “memory loss” if the individual being screened states that they have memory loss but do not have an accompanying diagnosis of dementia. The LTCFS is used to determine functional eligibility for long-term care programming and uses the results of the screens independently. The scoring key for the Memory Screening in the Community Program to determine if a referral is recommended is attached in Appendix E.

The Animal Naming tool is a categorical fluency test. The person is asked to recall specific labels for items in a specified category, such as animals. The tool is scored by tallying the number of correct responses. If the person names fewer than 14 correct animals, that is considered “not passing.”

The Mini-cog has two areas that are scored. Three points are awarded for recalling the three words correctly, and a score of either zero or two is awarded for the clock draw. For the three- word recall, one point is given for each word remembered. The words do not have to be in the same order in which they were presented.

The clock draw test requires some interpretation by the screener. The rules for scoring the clock draw are attached inAppendix G. There are examples of clocks drawn by participants in the pilot study that can be used to practice interpreting results in Appendix H. It is important not to overthink the interpretation of the clock; the clock is only one piece of the screening program. If a clock drawing looks correct but there are some questionable features, use your best professional judgment to make a decision and then move on.

The screens are conversation tools and do not provide a diagnosis; they are used to determine the need for an appropriate referral to a physician. If the scores from the screens do not indicate the need to make a referral to a physician, but the conversation about the individual’s memory concerns suggests that a referral would be helpful, a referral should still be offered.

The AD8 is scored by tallying the number of items noted as “Yes, a change.” If the score is two or more, a referral to the physician is appropriate. The instructions for determining the score of the AD8 can be found after the screening questions on the AD8 tool.

Training for the scoring of the MoCA tool can be found on the MoCA website. The MoCA is available to be used digitally, which can assist in scoring the results.

The screener can also offer to send in screening results for individuals whose scores do not fall into the range where a referral is recommended for the purposes of providing a baseline screen for their medical records. A baseline score is useful in detecting change over time. If an individual has several years of baseline scores in his or her record, detecting a change in cognitive abilities is easier to track and therefore easier to detect and respond accordingly.

If the person who was screened chooses to have the screening results shared with a physician, the screener must first obtain a signed ‘release of confidential information’ form giving permission to the screener to share the information. An example of this type of form is located in Appendix I, although most agencies will have their own form that must be used for this purpose.

Sending the screening results to the physician is also an opportunity to make the physician aware of the agency and its services as well as the community screening program. Cover letters should include information about the person who was screened, a short explanation of the screening process, information about the agency and a statement encouraging the physician to refer patients who receive a diagnosis back to the agency for ongoing support. A sample letter to the physician is attached in Appendix J.

The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute (WAI) and the dementia care specialist from Eau Claire County developed additional resources for use after the tools have been completed. For individuals whose screening results show they should talk to their doctor, Dr. Cindy Carlsson at the WAI developed a one-page document to accompany screening results sent to the physician by the screener. The document includes best practices around evaluation for possible dementia and when to refer a patient to the WAI Memory Diagnostic Clinics network. This resource can be found inAppendix K. Appendix L is the Memory Screening Results and Recommendations form available to provide the person after screening and is optional. Having the results and recommendations written in one place can be helpful to the person. Additional information and resources can be provided at the time or sent in a follow-up correspondence.

Once the tools are completed and a physician referral is recommended, the screener should ask permission to follow up after two to six months, even if the individual does not want the results sent to the physician. Agreeing to a follow-up call indicates openness to additional support in the future. If the person who was screened does indeed have dementia, they will need information and support in the future, and following up after a screen can allow that to happen in a planful way and not in crisis.

The Memory Screening in the Community Program can be provided in a variety of settings. Typically, screens are available whenever a customer requests a screen, or when a trained ADRC specialist or dementia care specialist identifies a customer that would benefit from the program. They are also usually performed in person. This can be during a home visit or office visit scheduled for another purpose. However, there are many possible locations for memory screening to be performed in the community. Partnering with municipal and other local governmental agencies to offer screens is one option. For example, public libraries are welcoming places free from the stigma associated with dementia and are often willing to host screening events in a private study room or other private space. Community or large employer health fairs also offer opportunities to screen, and to normalize screening for cognitive decline along with other health conditions.

County-based programs, healthy aging programs, public health departments, and other community-based partner agencies may also have staff trained and supported by the dementia care specialist at the ADRC to provide the Memory Screening in the Community Program. The same requirements for fidelity, oversight, and yearly refresher training apply to all screeners trained by the DCS.

The Memory Screening in the Community Program was adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic to be available virtually. When the program cannot be provided in person, there is a substitute protocol for use of the program virtually. Please consult Section IV: Accessibility and Health Equity Considerations for a description of the adaptation for virtual access.

modifiable factors such as educational attainment which tend to have protective effects against dementias may result in an overestimate for future decades. We

losses in white matter essential for communication between brain regions [30, 34, 35, 51, 56]. Reduced cortical thickness in the posterior cingulate gyrus is

No, many older adults live their entire lives without developing dementia. Normal aging may include weakening muscles and bones, stiffening of arteries and vessels, and some age-related memory changes that may show as:

A healthcare provider can perform tests on attention, memory, problem solving and other cognitive abilities to see if there is cause for concern. A physical exam, blood tests, and brain scans like a CT or MRI can help determine an underlying cause.

Alzheimer’s disease. This is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60 to 80 percent of cases. It is caused by specific changes in the brain. The trademark symptom is trouble remembering recent events, such as a conversation that occurred minutes or hours ago, while difficulty remembering more distant memories occurs later in the disease. Other concerns like difficulty with walking or talking or personality changes also come later. Family history is the most important risk factor. Having a first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s disease increases the risk of developing it by 10 to 30 percent.

Lewy body dementia. In addition to more typical symptoms like memory loss, people with this form of dementia may have movement or balance problems like stiffness or trembling. Many people also experience changes in alertness including daytime sleepiness, confusion or staring spells. They may also have trouble sleeping at night or may experience visual hallucinations (seeing people, objects or shapes that are not actually there).

Fronto-temporal dementia. This type of dementia most often leads to changes in personality and behavior because of the part of the brain it affects. People with this condition may embarrass themselves or behave inappropriately. For instance, a previously cautious person may make offensive comments and neglect responsibilities at home or work. There may also be problems with language skills like speaking or understanding.

Mixed dementia. Sometimes more than one type of dementia is present in the brain at the same time, especially in people aged 80 and older. For example, a person may have Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. It is not always obvious that a person has mixed dementia since the symptoms of one type of dementia may be most prominent or may overlap with symptoms of another type. Disease progression may be faster than with one kind of dementia.

Reversible causes. People who have dementia may have a reversible underlying cause such as side effect of medication, increased pressure in the brain, vitamin deficiency, and thyroid hormone imbalance. Medical providers should screen for reversible causes in patients who are concerning for dementia.

The memory impairment screen (MIS) is a brief screening tool to assess memory. It is often used as a preliminary test, along with other screening tools, to evaluate the cognition of someone who seems to display some possible impairment in their ability to think and recall.

The MIS is one of three tools recommended for use in the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit by the Alzheimer"s Association. The other two are the GPCOG and the Mini-Cog.

Four words in large print (24 font or larger) are shown to Maude and she is asked to read each item aloud. For example, the four words may be checkers, saucer, telegram, and Red Cross.

Maude is then given a category and asked to identify which word fits that category. For example, the category of "games" is provided and she must be able to identify that the word "checkers" fits that category. After completing this task for all four words on the paper, the paper is removed from sight and Maude is told that she will have to remember these words in a few minutes.

Next, Madue is asked to perform a task that distracts her from the four words she just learned, such as counting to 20 forwards and backwards or counting backwards by sevens starting at 100.

If more than 10 seconds have passed with no words recalled, Maude is then given the categorical clue for each word and asked to recall the word. For example, the test administrator will say that one of the items was a game and this might prompt Maude to remember the word "checkers." This is the cued recall section of the test.

For each word recalled without any clues (free recall), Maude will receive two points. For each word recalled with the categorical clue, Maude will receive one point.

Performance on the MIS shows little effect from education level. (Someone who has gone to school through 6th grade should be able to perform just as well as someone with a college education.)

Remember that the MIS is a screening tool, not a definitive diagnostic tool. Poor performance on the MIS indicates that there may be a reason to be concerned, but a full physician assessment is necessary to evaluate cognition and eventually diagnose dementia. Keep in mind that there are some causes of memory impairment that can be at least partially reversible with diagnosis and appropriate treatment, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, medication interactions, delirium, and normal pressure hydrocephalus.

In our later years, memory issues are common, leaving even the sharpest senior occasionally forgetful. When these issues happen more often or begin to interfere with daily tasks, it could signal something more. A simple screening tool is available that can determine if symptoms warrant a full evaluation. The screen is quick and is an annual recommendation with other checkups. When it comes to early intervention, memory screens offer insight into the unknown.

Memory screens are a brain checkup, if you will. The screen assesses memory and different types of thinking skills through a series of questions and tasks. It takes about 20 minutes to complete and is done by a qualified health professional or your doctor. While the screen cannot diagnose any condition, it can indicate if the person would benefit from a full evaluation.

Early intervention in conditions like Alzheimer’s means you get to play an active role in your care for longer and often have a better treatment response in earlier stages. A full evaluation and additional testing may also reveal if your memory issues are related to an underlying medical condition. Once treated, symptoms improve.

Anyone can develop Alzheimer’s or other dementia-related memory loss. Symptoms can begin as early as age 45, but most don’t know it till many years later. Memory screens are recommended once a year for adults 65 and older. Of course, those at higher risk or who are already experiencing memory issues should talk with their doctor about including a memory screen in their early intervention plan.

In the fight against Alzheimer’s and other dementias, hope can seemingly be as fleeting as the memories we hold dear. While there’s no cure for AD, early intervention methods help make patients’ journey a little easier. The earlier you know, the more time you have to plan, love, and ensure your legacy continues through the memories created.

Pacific Research Network offers free memory screens through our state-of-the-art neurological research facility. Set up your free screening today by calling us at (619) 294-4302 to request an appointment.

Although this may sound like the obvious and simple solution, my friends who are primary care providers remind me that they barely have time to do the basics — like blood pressure and diabetes management — and that they have no time to administer fancy cognitive tests. Even a simple test like the Mini-Cog (clock drawing and three words to remember) is too long for them. So how are we going to diagnose the increasing numbers of individuals with Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the next few decades?

In 2010, clinicians at the division of cognitive neurology in The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center developed a cognitive test to screen for memory loss that individuals can self-administer. This concept of a self-administered cognitive test can solve the problem of the time-crunched primary care provider. Individuals can take this test in the privacy of their own home and bring the results with them to the office. The results can then be used to determine whether additional work up and/or referral to a specialist is indicated.

To answer this question, the authors performed a retrospective chart review on 655 individuals seen in their memory disorders clinic, with a follow-up of up to 8.8 years. They compared their SAGE test to the MMSE.

Based on both initial and follow-up clinic visits, they divided their clinic population into four groups. Before I describe the groups, let me explain a few terms:

Even a self-administered test that individuals can do at home will still require training for primary care providers, to understand how the test should be used and how to interpret the results. There is no question, however, that such training will be worthwhile. Once the training is complete, the knowledge gained should be able to save literally thousands of hours of clinician time, in addition to missed — or improper — diagnoses.

Another question is how individuals will react when they are told that they need to perform a 10-to-15-minute cognitive test at home and bring the results to their doctor. Will they do it? Or will the ones who need the test the most avoid doing it — or cheat on it? My suspicion is that people who are concerned will do the test, as will people who generally follow their doctor’s instructions. Some individuals who would benefit from the information that the test provides may not do it, but many of those individuals wouldn’t do the "regular" pencil-and-paper testing with the doctor or clinic staff either.

Executive Functioning – Where is it Controlled and How Does it Develop? / Remediation Techniques for Deficits and Dysfunction [Internet]. Rainbow Rehabilitation Centers. 2017 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.rainbowrehab.com/executive-functioning/

Jahn H. Memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. Les Laboratoires Servier; 2013 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3898682/

Kirova, Anna-Mariya, B. R, Sarita. Working Memory and Executive Function Decline across Normal Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease [Internet]. BioMed Research International. Hindawi; 2015 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2015/748212/

Memory (Encoding, Storage, Retrieval) [Internet]. Noba. [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://nobaproject.com/modules/memory-encoding-storage-retrieval

Welcome to the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America’s Memory Screening Test [Internet]. AFA Online Memory Screening Test RSS. [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://afamemorytest.com/

Musical memory is considered to be partly independent from other memory systems. In Alzheimer’s disease and different types of dementia, musical memory is surprisingly robust, and likewise for brain lesions affecting other kinds of memory. However, the mechanisms and neural substrates of musical memory remain poorly understood. In a group of 32 normal young human subjects (16 male and 16 female, mean age of 28.0 ± 2.2 years), we performed a 7 T functional magnetic resonance imaging study of brain responses to music excerpts that were unknown, recently known (heard an hour before scanning), and long-known. We used multivariate pattern classification to identify brain regions that encode long-term musical memory. The results showed a crucial role for the caudal anterior cingulate and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area in the neural encoding of long-known as compared with recently known and unknown music. In the second part of the study, we analysed data of three essential Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in a region of interest derived from our musical memory findings (caudal anterior cingulate cortex and ventral pre-supplementary motor area) in 20 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (10 male and 10 female, mean age of 68.9 ± 9.0 years) and 34 healthy control subjects (14 male and 20 female, mean age of 68.1 ± 7.2 years). Interestingly, the regions identified to encode musical memory corresponded to areas that showed substantially minimal cortical atrophy (as measured with magnetic resonance imaging), and minimal disruption of glucose-metabolism (as measured with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography), as compared to the rest of the brain. However, amyloid-β deposition (as measured with 18F-flobetapir positron emission tomography) within the currently observed regions of interest was not substantially less than in the rest of the brain, which suggests that the regions of interest were still in a very early stage of the expected course of biomarker development in these regions (amyloid accumulation → hypometabolism → cortical atrophy) and therefore relatively well preserved. Given the observed overlap of musical memory regions with areas that are relatively spared in Alzheimer’s disease, the current findings may thus explain the surprising preservation of musical memory in this neurodegenerative disease.

Musical memory is relatively preserved in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. In a 7 Tesla functional MRI study employing multi-voxel pattern analysis, Jacobsen et al. identify brain regions encoding long-term musical memory in young healthy controls, and show that these same regions display relatively little atrophy and hypometabolism in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Musical memory entails the neural encoding of musical experiences. The relevant neuronal substrates have long been the object of research enquiry. In his seminal studies stimulating the cortex with electrodes, Wilder Penfield was the first to describe a possible role of the temporal cortex in the encoding of (episodic) musical memory (Penfield and Perot, 1963). Several more recent lesion studies support the hypothesis that temporal lobes are included in a musical memory network (Samson and Zatorre, 1991; Peretz, 1996; Samson and Peretz, 2005). However, musical memory seems not to rely solely on temporal lobe networks, a conclusion supported by evidence that recognition of a musical piece by a patient with bilateral temporal lobe lesion was enhanced by repeated exposure (Samson and Peretz, 2005).

It is likely that neural encoding of musical experiences is accomplished by more than one brain network (Baird and Samson, 2009). Attempts are often made to characterize musical memory in terms of established memory categories such as episodic/semantic, short-term/long-term, implicit/explicit, which are generally considered to be supported by different anatomical brain networks. For example it has been shown in a PET study that the underlying brain processes differ for semantic and episodic memory aspects of music, suggesting that they are based on two distinct neural networks (Platel et al., 2003). The anatomy of episodic musical memory has further been studied in a functional MRI experiment, using autobiographically relevant long-known musical pieces, which showed a crucial role for medial prefrontal and lateral prefrontal cortex, and for areas within the superior temporal sulcus and superior temporal gyrus (Janata, 2009). Several studies have investigated recognition (semantic) and recollection (episodic) during music presentation, finding distributed task involvement in temporal, prefrontal and auditory cortex. Musical memory clearly has many related aspects. Different types of music-related memory appear to involve different brain regions, for instance when lyrics of a song are remembered, or autobiographical events are recalled associated with a particular piece of music (Zatorre et al., 1996; Halpern and Zatorre, 1999; Platel et al., 2003; Satoh et al., 2006; Plailly et al., 2007; Watanabe et al., 2008; Brattico et al., 2011). The experimental design of the present study is intended to provide averaging over particular musical associations, to provide a simple comparison between unknown, recently-heard and long-known musical passages.

Musical memory may rely on distinct and task-dependent memory systems. It has been shown that memory for music can be severely damaged while other memory systems remain mostly unimpaired (Peretz, 1996). Conversely, musical memory was found to be preserved in severely amnestic patients with vast lesions of the right medial temporal lobe, the left temporal lobe and parts of left frontal and insular cortex, with similar findings in patients with bilateral temporal lobe damage (Eustache et al., 1990; McChesney-Atkins et al., 2003; Samson and Peretz, 2005; Finke et al., 2012). This strongly suggests that the network encoding musical memory is at least partly independent of other memory systems. Interestingly, it has been shown that different aspects of musical memory can remain intact while brain anatomy and corresponding cognitive functions are massively impaired (Baird and Samson, 2009; Finke et al., 2012).

Musical memory also appears to represent a special case in Alzheimer’s disease, in that it is often surprisingly well preserved (Vanstone and Cuddy, 2010), especially implicit musical memory, which may be spared until very late stages of the disease. Because these findings are mainly derived from case studies, it is not clear under what circumstances which aspect of musical memory is preserved (Baird and Samson, 2009; Johnson et al., 2011). Baird and Samson (2009) have indeed proposed that this preserved memory for music may be due to intact functioning of brain regions that are relatively spared in Alzheimer’s disease. However, this hypothesis has not yet received experimental support.

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, structural impairment typically develops along the hippocampal pathway (entorhinal cortex, hippocampus and posterior cingulate cortex) (Frisoni et al., 2010). Early degeneration is found mainly in the temporal and parietal lobes, the orbitofrontal cortex, the precuneus and in other large neocortical areas, while to a large degree the primary sensory, motor, visual, and anterior cingulate cortices are spared (Hoesen et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2003, 2007; Singh et al., 2006; Frisoni et al., 2007, 2010; Cuingnet et al., 2011; Villain et al., 2012; Lehmann et al., 2013). In vivo imaging of Alzheimer’s disease progression uses biomarkers to track anatomical changes in the human cortex. According to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, a disruption of balance between production and clearance of amyloid precursor protein leads to formation of amyloid-β plaques, development of neurofibrillary tangles, neural dysfunction, regional atrophy and finally dementia (Hardy and Higgins, 1992; Benzinger et al., 2013). Thus different in vivo imaging modalities are utilized to investigate amyloid-β deposition (18F-florbetapir PET), glucose hypometabolism [18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET] and cortical atrophy (structural MRI), which are all hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. In most parts of the brain the local development seems to consist of subsequent stages, amyloid-β accumulation, glucose hypometabolism, cortical atrophy, and finally cognitive decline (Benzinger et al., 2013). This holds for the majority of brain regions, but recent research also emphasizes that the local relationship between amyloid-β deposition and glucose hypometabolism, as well as cortical atrophy, is not consistent throughout the brain (La Joie et al., 2012; Benzinger et al., 2013).

Recent methodological developments of functional MRI analysis employing pattern classification provide a novel approach for investigating memory (Bonnici et al., 2012), by determining the coding of information in distributed patterns rather than by comparing brain activity levels in a voxel-wise fashion. This methodology is particularly effective in the analysis of ultra high-field (7 T) functional imaging data (Bode et al., 2011). As musical memory is known to be well preserved in

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey