display screens for memory impared free sample

Executive Functioning – Where is it Controlled and How Does it Develop? / Remediation Techniques for Deficits and Dysfunction [Internet]. Rainbow Rehabilitation Centers. 2017 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.rainbowrehab.com/executive-functioning/

Jahn H. Memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. Les Laboratoires Servier; 2013 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3898682/

Kirova, Anna-Mariya, B. R, Sarita. Working Memory and Executive Function Decline across Normal Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease [Internet]. BioMed Research International. Hindawi; 2015 [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2015/748212/

Memory (Encoding, Storage, Retrieval) [Internet]. Noba. [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://nobaproject.com/modules/memory-encoding-storage-retrieval

Welcome to the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America’s Memory Screening Test [Internet]. AFA Online Memory Screening Test RSS. [cited 2019Aug6]. Available from: https://afamemorytest.com/

The PMIS is a quick and reliable screen for dementia that can be used in older adults with little or no education. It discriminated cognitively normal older adults from those with dementia regardless of age, sex, education, severity of dementia, or presence of depression. All participants completed the PMIS, which took approximately 4 minutes including the interference task. High interrater reliability was demonstrated between administration of PMIS by the clinician and the nurse. The high alternate-forms reliability supports use of different PMIS sets for repeated testing. Professionals and nonprofessionals successfully administered the PMIS in urban and rural clinic settings. The PMIS was administered on a computer screen and using cards. These findings support the feasibility of using the PMIS in various settings and by personnel with different levels of expertise.

Pictures are remembered better than words. The visual component of the PMIS involves deeper or additional layers of cognitive processing; enhancing learning and recall. Poor visual memory predicts dementia,

Table 2 shows sensitivity and specificity based on the sample and PPV and NPV at hypothetical dementia base rates that can guide choice of cut-scores. A sensitive PMIS cut-score can be used to monitor cognitive function in older adults and guide timing of follow-up visits, whereas a specific cut-score with high PPV can be used to avoid false-positive cases when recruiting candidates for clinical trials involving potentially toxic medications.

The initial step in evaluating older adults presenting with cognitive complaints is to detect or exclude dementia regardless of subtype. Because the PMIS is a cognitive screening test, individuals who fail it should be referred for definitive diagnostic assessment. Alternatively, individuals scoring in the normal range could be asked to return for a repeat screen at a longer interval.

JEM Research Institute conducts clinical trials for Memory Loss, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, Vaccine studies for COVID-19, RSV, and Flu. We also offer treatment trials for Nephrology/Kidney disorders. All services are at no cost to the patient and/or their health insurance.

Screening for dementia, much like screening for other diseases or chronic conditions, is a good way to detect the changes that can be signs of the onset of disease or other change in cognition. Memory screening and early detection provide:The ability to make lifestyle and other beneficial changes earlier in the disease process when they have the greatest potential for positive effect.

Time to connect with community-based information and supportive services prior to a potential crisis situation related to the needs of the person with dementia or the caregiver.

To enable people with dementia and their caregivers to benefit from memory screening and early detection, a community-based memory screening program was developed by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services and the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute using the Animal Naming Screen, the Mini-cog, and the AD8.

The Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools were selected after a pilot study in Portage County in 2009. The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute, the Aging and Disability Resource Center (ADRC) of Portage County, and DHS demonstrated the acceptability and effectiveness of using the Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens in a community setting. The Animal Naming screen is attached as Appendix C (PDF) and the Mini-cog as Appendix D (PDF)

Results from the pilot demonstrated ADRC customers’ high level of acceptance of screening. The offer of a memory screen was accepted by 243 out of 254 people, a 96% acceptance rate. This result contradicts the idea that people do not want to be screened for dementia. The tools were also effective in detecting cognitive issues. Of the 243 people who were screened, 150 (63%) had results that indicated they should follow up with their physician. This result may seem surprisingly high, but screens were only offered to individuals who expressed a concern about their memory, so those with cognitive issues self-selected into the study. Of those 150 people, 120 or 80% agreed to have the results sent to their physician.

The Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens were selected not only for their acceptability and effectiveness, but also because they are brief, easy to administer and score, and are sensitive to early cognitive changes. Some screens must be administered by physicians or psychologists and can take more than an hour. The minimum level of training required and the short length of time necessary to administer the screens was a critical component in their acceptance for use by ADRC staff.

The screens were also selected because they have documented utility as dementia screens and tap key skills likely to be affected in mild to moderate dementia. The Animal Naming screen involves retrieval from semantic memory and executive function, two areas of cognition that reliably decline in people with Alzheimer’s disease. In a study of memory clinic clients with a high base rate of dementia, the Animal Naming screen was shown to have 85% sensitivity and 88% specificity for differentiating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia from normal cognition. The Mini-cog screen tests memory as well as visuoconstruction and executive function, with studies showing sensitivity for dementia of 76% to 99% and specificity of 83% to 93% in analyses that excluded patients with mild cognitive impairment.

Memory screens are voluntary, so there will be individuals who decline to participate. On these occasions, if family caregivers are uncertain whether their concerns about the person they are caring for are valid, the AD8 screen can help determine whether a visit to the doctor is recommended. The AD8 (PDF) tool is available in both English and Spanish. This screen is intended to help the caregiver think through the changes they see in a family member, and may help them to realize it is time to take action. The screen can be provided to the family caregiver to complete on their own, or the questions can be asked by the screener in a private setting. The AD8 has sensitivity for dementia of greater than 84% and a specificity of greater than 80%.

In 2020, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool was added to the approved tools for use by dementia care specialists (DCS). This tool is not for use by ADRC staff other than the DCS. The intention behind the addition of the MoCA screen is to give DCS an additional tool for situations that are more complex. While the Mini-cog and the Animal Naming screens are more sensitive to earlier changes than other screens, they are limited to a few areas of cognition. The MoCA covers a wider variety of cognitive tasks and provides additional insight into possible cognitive impairment when the Animal Naming and Mini-cog results do not reflect the changes in cognition and behavior reported by the individual or their family.

New dementia care specialists should become very familiar with the Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools prior to adding the MoCA to their toolkit. There are some similarities and some differences between the activities of the Animal Naming and Mini-cog and those in MoCA. Learning all the screens at the same time can be confusing, so it is advised for new staff to focus on the Animal Naming and Mini-cog screens, as well as the AD8, prior to becoming certified to provide the MoCA screen. Training and certification for the MoCA, and the approved form, are available from the official MoCA website. There is a cost to the training and certification for the MoCA. The MoCA is not required to be provided as a part of this program but is available as a supplemental tool.

The primary intent of this memory screening protocol is to enable and enhance conversations about memory concerns. The screens are not diagnostic tools and do not make any determinations about mental status. The screens are similar to a blood pressure check, in that a high blood pressure reading does not mean an individual has cardiovascular disease, but is a signal to talk to a physician about the results. The screens can be a reason to bring up the topic of memory issues because they can be offered in the moment. A referral to the physician can be more meaningful if an objective tool verifies that an individual’s concerns with memory and cognition should be further assessed.

It is appropriate to offer a memory screen when one is requested, or when working with a customer who displays signs of possible memory loss or confusion. ADRC specialists are able to offer the screening program during a visit for another purpose, if time allows. It is preferable to address the concerns around memory at the time, rather than putting off the discussion for another appointment. Memory screening is always voluntary.

Staff members may feel uncomfortable offering a memory screen if they are not used to asking and answering questions about memory and dementia. It is important that staff who are offering the screens understand why screening is important and helpful to the customer. Practicing offering the screen to coworkers and family members can be a good way to become more comfortable. Staff must be trained to follow the guidance in this manual before performing memory screens with the public.

If other people are present for the screening, let them know they will need to remain quiet and not help the person answer the questions. Ensure the participant cannot easily view and copy a clock in the room.

Begin with Animal Naming. It is critical to read the instructions for each task on both screens exactly as they are written. Do not explain how the screen is scored prior to performing the screen, and only afterwards if the individual asks you to do so. To adhere to the fidelity of the tools, they must be performed exactly the same way every time to ensure the results are valid. Read the instructions to the participant: “Please name as many animals as you can think of as quickly as possible.” Be prepared for the person to start listing animals immediately or, if they do not, prompt them with “Go.”

Once the person begins to name animals, start the timer and record all the animals named within 60 seconds in the spaces provided on the worksheet. If the person is speaking quickly, write as much of the word as needed to remember what was said and fill in the remaining letters afterward. If the person falls silent, follow the prompting instructions. Once the Animal Naming screen is done, administer the Mini-cog, even if the score of the Animal Naming screen was very high. The two screens should always be used together.

The Memory Screening in the Community program is intended for the Animal Naming tools and the Mini-cog tool to be used in combination. In this non-clinical program, the standard Mini-cog tool available online has been adapted to work in concert with the Animal Naming Tools. Refer to Appendix D to access the form to record results.

Begin the Mini-cog by telling the participant, “I am going to say three words I want you to remember,” and repeat the three words listed on the worksheet. Be sure to read the instructions exactly as they are written. It is important to the fidelity of the screen to use the same three words every time the screen is performed. Give the participant three chances to repeat the words back. If the participant does not repeat the words, or does not repeat them correctly, the screener can repeat the words up to three times until the words are repeated correctly. If they are not correct after the third time, move on to the clock draw.

Provide a blank, standard, letter-size sheet of paper for the participant to draw on and a writing utensil. This can be the back of the Animal Naming worksheet or another blank sheet. Allow the participant time to adjust to the new task, pick up the writing utensil, and adjust the paper. Once the participant is settled, read the instructions for the clock draw exactly as they are written, pausing when indicated to allow the participant to complete the task. Move on from this task if the clock is not complete within three minutes.

There will be individuals that frequently request to be screened. If they express the desire for an alternate set of words used for the three-word recall portion, refer to the words listed in the Health Equity section for Hmong translation. The need for an alternative set of words was first identified in the need for the translation of the words into Hmong. they do not easily translate into that language, so an alternative set of words was identified for that purpose. That substitution can also be applied for individuals who request frequent screening.

The AD8 can be administered to the person with possible memory loss, but often individuals with dementia lose insight into their condition and are not reliable self-reporters. The questions on the screen can either be read aloud or a caregiver can fill out the form on their own. In situations where the person with possible memory loss is together with the caregiver, allowing the caregiver to fill out the questionnaire silently may be less upsetting for the person with possible memory loss than if the questions are asked aloud. The caregiver may also provide different answers if the person with possible memory loss is listening to the answers.

The MoCA tool, including training, certification, and the downloadable version of the paper tool can be found on the MoCA website. The MoCA is also available to be used digitally. Instructions for how the MoCA tool is scored are a part of the training and certification process.

The Memory Screening in the Community program was adapted in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic for use when screening was required to be completed virtually. The ability to provide screening virtually for dementia risk has been identified as an ongoing need. Please consult Section IV: Accessibility and Health Equity Considerations for a description of the adaptation for virtual access.

The use of the Animal Naming and Mini-cog tools in the Memory Screening in the Community Program is different than as a part of Wisconsin’s Long-Term Care Functional Screen (LTCFS). The purposes for the use of these tools in the Memory Screening in the Community Program are to enable a conversation and assist in determining whether speaking to a physician is advisable. The LTCFS uses the tools to represent “memory loss” if the individual being screened states that they have memory loss but do not have an accompanying diagnosis of dementia. The LTCFS is used to determine functional eligibility for long-term care programming and uses the results of the screens independently. The scoring key for the Memory Screening in the Community Program to determine if a referral is recommended is attached in Appendix E.

The Animal Naming tool is a categorical fluency test. The person is asked to recall specific labels for items in a specified category, such as animals. The tool is scored by tallying the number of correct responses. If the person names fewer than 14 correct animals, that is considered “not passing.”

The Mini-cog has two areas that are scored. Three points are awarded for recalling the three words correctly, and a score of either zero or two is awarded for the clock draw. For the three- word recall, one point is given for each word remembered. The words do not have to be in the same order in which they were presented.

The clock draw test requires some interpretation by the screener. The rules for scoring the clock draw are attached inAppendix G. There are examples of clocks drawn by participants in the pilot study that can be used to practice interpreting results in Appendix H. It is important not to overthink the interpretation of the clock; the clock is only one piece of the screening program. If a clock drawing looks correct but there are some questionable features, use your best professional judgment to make a decision and then move on.

The screens are conversation tools and do not provide a diagnosis; they are used to determine the need for an appropriate referral to a physician. If the scores from the screens do not indicate the need to make a referral to a physician, but the conversation about the individual’s memory concerns suggests that a referral would be helpful, a referral should still be offered.

The AD8 is scored by tallying the number of items noted as “Yes, a change.” If the score is two or more, a referral to the physician is appropriate. The instructions for determining the score of the AD8 can be found after the screening questions on the AD8 tool.

Training for the scoring of the MoCA tool can be found on the MoCA website. The MoCA is available to be used digitally, which can assist in scoring the results.

The screener can also offer to send in screening results for individuals whose scores do not fall into the range where a referral is recommended for the purposes of providing a baseline screen for their medical records. A baseline score is useful in detecting change over time. If an individual has several years of baseline scores in his or her record, detecting a change in cognitive abilities is easier to track and therefore easier to detect and respond accordingly.

If the person who was screened chooses to have the screening results shared with a physician, the screener must first obtain a signed ‘release of confidential information’ form giving permission to the screener to share the information. An example of this type of form is located in Appendix I, although most agencies will have their own form that must be used for this purpose.

Sending the screening results to the physician is also an opportunity to make the physician aware of the agency and its services as well as the community screening program. Cover letters should include information about the person who was screened, a short explanation of the screening process, information about the agency and a statement encouraging the physician to refer patients who receive a diagnosis back to the agency for ongoing support. A sample letter to the physician is attached in Appendix J.

The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute (WAI) and the dementia care specialist from Eau Claire County developed additional resources for use after the tools have been completed. For individuals whose screening results show they should talk to their doctor, Dr. Cindy Carlsson at the WAI developed a one-page document to accompany screening results sent to the physician by the screener. The document includes best practices around evaluation for possible dementia and when to refer a patient to the WAI Memory Diagnostic Clinics network. This resource can be found inAppendix K. Appendix L is the Memory Screening Results and Recommendations form available to provide the person after screening and is optional. Having the results and recommendations written in one place can be helpful to the person. Additional information and resources can be provided at the time or sent in a follow-up correspondence.

Once the tools are completed and a physician referral is recommended, the screener should ask permission to follow up after two to six months, even if the individual does not want the results sent to the physician. Agreeing to a follow-up call indicates openness to additional support in the future. If the person who was screened does indeed have dementia, they will need information and support in the future, and following up after a screen can allow that to happen in a planful way and not in crisis.

The Memory Screening in the Community Program can be provided in a variety of settings. Typically, screens are available whenever a customer requests a screen, or when a trained ADRC specialist or dementia care specialist identifies a customer that would benefit from the program. They are also usually performed in person. This can be during a home visit or office visit scheduled for another purpose. However, there are many possible locations for memory screening to be performed in the community. Partnering with municipal and other local governmental agencies to offer screens is one option. For example, public libraries are welcoming places free from the stigma associated with dementia and are often willing to host screening events in a private study room or other private space. Community or large employer health fairs also offer opportunities to screen, and to normalize screening for cognitive decline along with other health conditions.

County-based programs, healthy aging programs, public health departments, and other community-based partner agencies may also have staff trained and supported by the dementia care specialist at the ADRC to provide the Memory Screening in the Community Program. The same requirements for fidelity, oversight, and yearly refresher training apply to all screeners trained by the DCS.

The Memory Screening in the Community Program was adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic to be available virtually. When the program cannot be provided in person, there is a substitute protocol for use of the program virtually. Please consult Section IV: Accessibility and Health Equity Considerations for a description of the adaptation for virtual access.

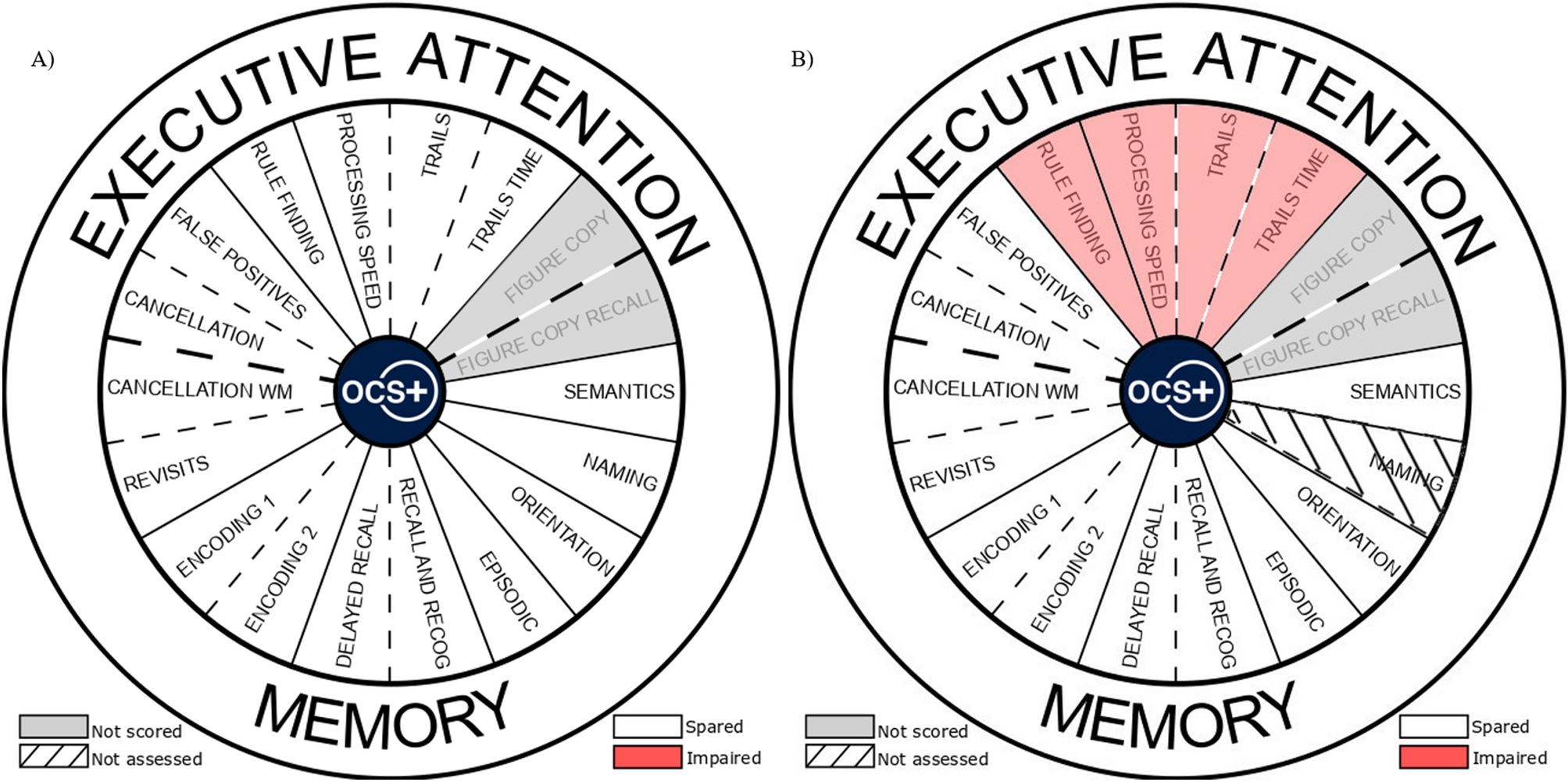

To determine how close the patient’s cognitive abilities are to a sub-group with similar educational backgrounds, the patient’s abilities are measured in eight ways. These results are then compared against the distribution of test results for others having similar education.

Taking into account test scores, longitudinal patterns, and other background information (e.g., age, education, depression, pain medication, solvent exposure, alcohol use, head injuries, and exercise), Screen develops an overall probability that if the patient were tested by the “gold standard” of a full neuropsychological evaluation, it would confirm the presence or absence of MCI. (Note: the “gold standard” referenced here is the full battery of neuropsychological tests that Screen measured itself against in a major study: it was administered by a completely independent neuropsychologist, took hours of face-to-face time, and cost approximately $2,000 per subject).

Also, in a separate study(2), Screen explicitly evaluated its test battery against an actual, independent, full neuropsychological exam (the “gold standard” costing $2,000 per patient report) to see if the CANS-MCI could accurately predict the people who, when given the full neuropsychological exam, would be classified as having MCI. Although Screen’s test battery only cost a small fraction of the amount for a full, in-person battery, it predicted nearly identically which people would be classified by the gold standard as having MCI or as normal-functioning.

Although this may sound like the obvious and simple solution, my friends who are primary care providers remind me that they barely have time to do the basics — like blood pressure and diabetes management — and that they have no time to administer fancy cognitive tests. Even a simple test like the Mini-Cog (clock drawing and three words to remember) is too long for them. So how are we going to diagnose the increasing numbers of individuals with Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the next few decades?

In 2010, clinicians at the division of cognitive neurology in The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center developed a cognitive test to screen for memory loss that individuals can self-administer. This concept of a self-administered cognitive test can solve the problem of the time-crunched primary care provider. Individuals can take this test in the privacy of their own home and bring the results with them to the office. The results can then be used to determine whether additional work up and/or referral to a specialist is indicated.

To answer this question, the authors performed a retrospective chart review on 655 individuals seen in their memory disorders clinic, with a follow-up of up to 8.8 years. They compared their SAGE test to the MMSE.

Based on both initial and follow-up clinic visits, they divided their clinic population into four groups. Before I describe the groups, let me explain a few terms:

Even a self-administered test that individuals can do at home will still require training for primary care providers, to understand how the test should be used and how to interpret the results. There is no question, however, that such training will be worthwhile. Once the training is complete, the knowledge gained should be able to save literally thousands of hours of clinician time, in addition to missed — or improper — diagnoses.

Another question is how individuals will react when they are told that they need to perform a 10-to-15-minute cognitive test at home and bring the results to their doctor. Will they do it? Or will the ones who need the test the most avoid doing it — or cheat on it? My suspicion is that people who are concerned will do the test, as will people who generally follow their doctor’s instructions. Some individuals who would benefit from the information that the test provides may not do it, but many of those individuals wouldn’t do the "regular" pencil-and-paper testing with the doctor or clinic staff either.

The memory impairment screen (MIS) is a brief screening tool to assess memory. It is often used as a preliminary test, along with other screening tools, to evaluate the cognition of someone who seems to display some possible impairment in their ability to think and recall.

The MIS is one of three tools recommended for use in the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit by the Alzheimer"s Association. The other two are the GPCOG and the Mini-Cog.

Four words in large print (24 font or larger) are shown to Maude and she is asked to read each item aloud. For example, the four words may be checkers, saucer, telegram, and Red Cross.

Maude is then given a category and asked to identify which word fits that category. For example, the category of "games" is provided and she must be able to identify that the word "checkers" fits that category. After completing this task for all four words on the paper, the paper is removed from sight and Maude is told that she will have to remember these words in a few minutes.

Next, Madue is asked to perform a task that distracts her from the four words she just learned, such as counting to 20 forwards and backwards or counting backwards by sevens starting at 100.

If more than 10 seconds have passed with no words recalled, Maude is then given the categorical clue for each word and asked to recall the word. For example, the test administrator will say that one of the items was a game and this might prompt Maude to remember the word "checkers." This is the cued recall section of the test.

For each word recalled without any clues (free recall), Maude will receive two points. For each word recalled with the categorical clue, Maude will receive one point.

Performance on the MIS shows little effect from education level. (Someone who has gone to school through 6th grade should be able to perform just as well as someone with a college education.)

Remember that the MIS is a screening tool, not a definitive diagnostic tool. Poor performance on the MIS indicates that there may be a reason to be concerned, but a full physician assessment is necessary to evaluate cognition and eventually diagnose dementia. Keep in mind that there are some causes of memory impairment that can be at least partially reversible with diagnosis and appropriate treatment, such as vitamin B12 deficiency, medication interactions, delirium, and normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Memory loss can disrupt your daily life and may be a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia. Are you or a loved one feeling concerned about memory loss?

Grayline Research Center is proud to offer free confidential memory screens for individuals who have concerns about their memory or want to check their memory now for future comparison.

All memory screens are performed by staff who are trained in identifying problems with memory or thinking. The screening is non-invasive, consists of a series of questions and tasks, and takes around 30 minutes to administer.

Memory screenings are used as an indicator of whether a person might benefit from an extensive medical exam, but they are not used to diagnose any illness and in no way replace an exam by a qualified healthcare professional. We encourage medical follow up.

Encourage those with memory problems to follow up with an exam by a physician or other qualified healthcare professional for an accurate diagnosis, treatment, social services, and community resources

*Because we are screening for memory concerns, we recommend you attend the Free Memory Screen with a trusted individual. If you are scheduling a memory screen appointment for someone other than yourself, please indicate this when you call to schedule an appointment.

By default, the RAZ Memory Phone displays up to six pictures of contacts. If memory loss is more severe, the phone can display only one or two pictures.

When the phone rings, two big buttons will appear. A green one that says “Answer” and a red one that says, “Hang up”. If the caller is a contact, a large picture and name of the caller will be displayed.

The RAZ Memory Cell Phone is the only cell phone specifically designed for seniors with dementia or Alzheimer’s, although it is also a good choice for some seniors who just want a very simple experience. The cell phone is based on 3 design principles: (1) it is incredibly easy to use for the senior, (2) the phone can be managed from afar through a feature called Remote Manage, and (3) every additional capability offered by the phone is optional.

The RAZ Memory Cell Phone has one primary screen. The screen accommodates up to 6 contacts with an option for up to 30, with contact pictures and names underneath. The pictures help individuals with dementia who cannot always remember the names of their contacts or who may have difficulty reading. There is also a button to call 911; the user does not have to enter the digits. To make calls, the senior taps and holds the picture of the person they want to call. That’s it! There is no menu system, no apps, no ability to access settings …etc.

With simplicity in mind, the phone’s volume button is disabled and is always set to maximum, the screen does not lock or go to “sleep” (the display is always on), and even the power button can be disabled. Here is a demonstration video of the RAZ Memory Cell Phone.

Normally a cell phone’s features are managed in device settings or in individual applications. In the case of the RAZ Memory Cell Phone, to maximize simplicity and to accommodate the fact that many caregivers do not live with their loved ones, the cell phone is managed through a feature called Remote Manage. Remote Manage allows caregivers to manage all aspects of the RAZ Memory Cell Phone from afar, using a mobile application or an online portal.

Receive text message alert when battery is low –The care partner will receive a text message when the battery of the RAZ Memory Cell Phone decreases to a specified level.

Reminders –Remind your senior about events or things they should do. A sticky note will appear on the RAZ Memory Cell Phone, and there is an option for an audio message, as well.

RAZ Emergency Service – The RAZ Memory Cell Phone includes a dedicated 9-1-1 button. The senior simply presses the button to contact emergency services. If the senior has the habit of repetitively calling 9-1-1, which is not uncommon for individuals with more advanced dementia or Alzheimer’s, the care partner can subscribe to the RAZ Emergency Service for $79.99 per year. Calls are routed to a private dispatch service and the dispatch agents know that the caller suffers from memory loss. Also, care partners are notified of emergency calls by text message and can “cancel” the emergency.

The RAZ Memory Cell Phone is a smartphone with a 6.5-inch display, which provides a lot of real estate for contacts and their pictures. The large display also helps people with vision loss. It has a modern “tear-drop” design with minimal bezels. Nobody can tell from the design that the phone is for seniors with dementia or Alzheimer’s, which means that users will not feel self-conscious that they have a “special” phone.

The display itself is very bright. It dims a little when it has not been used for 2 minutes in order to save battery power. Even in this dimmed state, it can be seen easily by seniors. As soon as the user touches the dimmed display, it brightens.

The price of the RAZ Memory Cell Phone is $349.00 and works on all major wireless providers, including Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, Consumer Cellular, Mint Mobile, Affinity Cellular, and other compatible networks. The phone is unlocked. In other words, the user can select his or her wireless provider and plan. Currently, the phone comes with a free SIM card and three (3) free months of service from either MINT Mobile or Affinity Cellular.

The KidsConnect KC2 Phone is designed for children. The company website describes the phone as a parent’s “All In One Security Solution”. Nevertheless, the phone is sometimes purchased for individuals with dementia or Alzheimer’s as a result of its simplicity.

The senior can call up to three (3) contacts with the physical speed dial buttons. There are no pictures displayed on the cell phone, so the user must remember which contact is associated with each number. To place a call, the senior must press and hold the speed dial button for three (3) seconds. An additional twelve (12) people can be contacted with the touch screen. To make calls with the touch screen, the senior must tap “Phone” and then tap the number that they wish to call. Again, there are no pictures. Depending on the user’s level of dementia or Alzheimer’s, navigating this menu system may or may not be possible. Watch a video to see the basic operation of KidsConnect.

The phone cannot dial 911, but it does have an SOS button that will call and send text messages to up to three numbers. The text message will say that an SOS has been triggered. The inability to call 911 may be a deal-breaker for some.

The phone offers GPS tracking and geo-fencing, which may be very useful features for finding a wandering senior with dementia. The phone also offers text messaging, a stopwatch, and access to settings through the touchscreen menu system. These additional features add some complexity to the device and may be confusing to individuals with dementia or Alzheimer’s.

Unlike with the RAZ Memory Cell Phone, the volume button is not locked down, so the user can inadvertently lower the volume without realizing it. Further, like many cell phones, the KidsConnect locks after a certain period of time. Some users may have difficulty unlocking their cell phone.

The price of the KidsConnect phone on the KidsConnect website is $199.95. Wireless plans are purchased through the KidsConnect website and cost $45/month for unlimited service with T-Mobile coverage and $60/month for unlimited service with AT&T coverage.

Unlike the RAZ Memory Cell Phone or the KidsConnect KC2, incoming calls cannot be limited to contacts. Thus, if you are concerned about the senior being taken advantage of by predatory telemarketers, the Jitterbug Flip2 is probably not a good option.

The Jitterbug Flip2 is really all about the health services. It advertises itself as a “personal safety device.” The Basic health and safety package is priced at $19.99 per month (on top of the cost of your cell phone service), and most notably includes a private emergency dispatch service, as well as a service that sends medication reminders. There is also a Preferred package for $24.99 and an Ultimate package for $34.99. The Preferred package includes access to a board-certified doctor or nurse without an appointment. The Ultimate package includes a personal operator that can help the user with tasks, such as looking up addresses or phone numbers. These services are accessed by pressing the 5Star Button.

The Jitterbug Flip2 supports other features, including text messaging, a camera, call history, a flashlight, magnifier, clock, calculator, and FM Radio. It also has Amazon Alexa, which allows the senior to ask it for information, such as the weather. It does not support video calls.

The date and location of a free “memory screening” event at the UCSD Shiley-Marcos ADRC was announced in print and on-line versions of an English language newspaper article on aging and brain health published by the San Diego Union-Tribune in early January 2017 and again in early January 2018. The announcements noted that screening was available for any adult 65 years of age or older with concerns about his or her memory. A phone number was provided for contacting the ADRC to schedule a screening appointment. Due to the enthusiastic response (e.g., over 150 calls on the day after the first article), three separate “Memory Screening Day” events were scheduled each year to accommodate the demand. These events occurred in January, April, and July 2017, and January, May, and September 2018. Each event occurred during a single day that could accommodate up to 120 participants. Screening appointments were made on a first-come, first-served basis with the appointments rolling to the next event once the first event of the year was fully scheduled (although we scheduled 132 individuals for one of the events with anticipation of “no shows”). The overflow events continued to be advertised through the ADRC newsletter and ADRC website. Three events were able to accommodate all of those who expressed a desire to be screened in a given year. Screening required 30 min and was carried out individually. Eight screens were simultaneously performed by eight raters in separate testing rooms, with each rater completing 13 to 15 screens during the event. This accommodated a total of 104 to 120 participants during each event.

When participants called to inquire or make an appointment, an ADRC staff member answered general questions, obtained their age and contact information, and scheduled a specific time for screening. A map with detailed directions to the screening location at the UCSD ADRC and instructions for free parking were sent to the participant. The staff member called the participant close to their appointment date (2–3 days before) to remind them of the time and place.

Prior to cognitive testing, informed consent was obtained from each participant for use of screening data for research purposes. Consent was obtained by the rater who performed cognitive testing. During the consent process, participants were made aware that their data would be de-identified and kept confidential and that they could withdraw consent for research at any time. They were also informed that the results and information provided through screening were preliminary and educational in nature and intended to provide information to facilitate a meaningful discussion with their physician or other qualified healthcare professional. They were told that the results were not intended to provide a diagnosis or recommendation for treatment or rehabilitation and do not and should not take the place of talking with their physician or other qualified healthcare professional. They were also told that if they declined to consent to have their memory screening data used for research purposes, they would still be screened and given the results, but the data would not be saved or used in any analyses. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the UCSD Human Research Protection Program (HRPP)/Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Participants then completed screening cognitive testing and a demographics questionnaire (i.e., date of birth, years of education, gender), a language history questionnaire, and a brief, 10-point self-report scale of memory concerns (i.e., Memory Concerns Questionnaire; MCQ). Finally, participants were offered the opportunity to receive additional debriefing about their screening results, information about resources for those with memory concerns, and information about opportunities for participation in research related to memory disorders and aging. They were also asked to complete additional questionnaires about their potential willingness to participate in various types of research and research procedures.

Raters included ADRC psychometrists and designated research assistants from local scientific collaborators who draw on ADRC research participants for their studies. All raters completed a 4-h training session with a senior psychometrist that involved a discussion of general testing protocol, strategies to reassure and encourage participants who are anxious, a review of Health Insurance Portability and Assurance Act (HIPAA) requirements, and detailed administration and scoring training on the neuropsychological tests used in the screening process. There was also detailed training on the use of the algorithm needed to complete the feedback letter (see below). Bilingual staff members with demonstrated Spanish-English fluency were available to provide testing in either language, depending on the participant’s self-reported preference.

Each participant was tested in a quiet, well-lit room at the Shiley-Marcos ADRC by a trained rater. The screening battery consisted of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scale [16] and the immediate and delayed recall conditions of Story A from the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) [17]. The MoCA is a brief mental status exam that assesses attention, concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visual constructional skills, conceptual thinking, calculations, and orientation. Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better performance. An education adjustment is built into the MoCA so that 1 point is added to the total score for those with 12 years of education or less. The WMS-R Logical Memory, Story A is a measure of verbal episodic memory. A short, one-paragraph story that consists of 25 elements of information is read aloud to the participant who must then immediately recall as many elements of the story as possible. The participant is told to remember the story for later recall and 20 to 30 min later is asked to recall the story again (a cue is given if necessary). The number of story elements recalled immediately and after the delay interval is recorded. One point is awarded for each element recalled for a maximum total score of 25 for each condition (immediate, delay). The delay interval is filled with a demographic survey and administration of the MoCA.

For those who preferred to be tested in Spanish, the screening battery consisted of Spanish translations of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE [18];) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Memory Test [19]. Different tests were used for Spanish and English speakers based on the availability of appropriate translations and normative data. The MMSE is a global mental status test that briefly assesses orientation to time and place, word list registration, attention, word list recall, and language. Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better performance. The CERAD Memory Test is a list learning test in which a participant is asked to read aloud and remember 10 common words as they are visually presented one by one, and then to immediately recall as many of the words as possible. This read-and-recall procedure is repeated across three learning trials. After a 5-min delay (filled with a drawing task), the participant is again asked to recall as many words as possible. Finally, a yes-no recognition test is presented for the 10 words randomly interspersed with 10 distractor words.

Immediately after cognitive testing, the rater scored the two test measures (e.g., MoCA, story recall), determined z-scores using formulas based on age- and education-adjusted normative data, and used the z-scores with the algorithm shown in Table 1 to determine the participant’s cognitive classification. An education-adjusted MoCA score less than 24 was used to differentiate abnormal from normal performance based on normative data from general community populations [20, 21]. A Logical Memory delayed recall score at least 1.5 standard deviations below the expected age and education normative score was used to differentiate abnormal from normal performance. Normative data used for this calculation was from the large National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC UDS) normal sample [22]. Cutoff scores for the MMSE and CERAD Memory Test used for Spanish language testing were 1.5 standard deviations below the expected age- and education-adjusted scores derived from longitudinal data from the UCSD Shiley-Marcos ADRC [23].

Table 1 Classification algorithms used for English and Spanish screening procedures. Classification was determined by a combination of performance on a test of delayed recall and a test of global mental status

Based on application of the algorithm, the participant received immediate written feedback from the rater that stated: “Normal, Age-Appropriate Cognition,” “Possible Decline in Cognition that is greater than expected,” or “Likely Decline in Cognition that is greater than expected.” It was emphasized that this was not a “diagnosis” but simply information that could be used by the participant to prompt interaction with his/her physician.

At the completion of testing, each participant was invited to visit a conference room with refreshments where they could meet with ADRC staff members to ask questions about their testing feedback, receive educational brochures about memory loss and potential causes of memory decline (including AD), and discuss local resources for those with memory concerns (e.g., Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s San Diego). Staff members reiterated that the screening result was not a “diagnosis” but simply information that should prompt interaction with their physician to determine “next steps.” The importance of further evaluation to verify memory decline and better understand its causes was emphasized, as was the importance of gaining knowledge about health/lifestyle factors that might reduce dementia risk.

Opportunities to participate in research on memory loss and dementia at the ADRC or affiliated studies were described by staff members. Those interested were invited to review and sign the UCSD IRB approved consent and HIPAA forms that allowed them to be contacted in the future about participating in specific ADRC-affiliated research projects, and permitted their demographic information and screening data to be added to a Research Registry maintained by the ADRC. The Research Registry is used to match participants’ research study preferences and eligibility with specific study requirements. These forms could be completed immediately or taken home so the participant could spend additional time considering whether research participation was an option they would like to pursue. If participants consented to taking part in additional research, they were asked to complete a research interest form which asked about their health history, the likely availability of a study partner (i.e., someone who knows them well enough to provide information about their activities of daily living), and their attitudes towards potential research procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lumbar puncture (LP), and autopsy.

Age and education, MCQ scores, and scores on the cognitive tests were compared across groups (Normal, Possible Decline, or Likely Decline) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s least-significant difference (LSD) tests for post hoc pair-wise comparisons when ANOVA results were significant. Distributions of the binary categorical variables sex, ethnicity (non-Hispanic, Hispanic), and family history (positive, negative) were compared using 2 × 3 (Normal, Possible Decline, or Likely Decline) chi-square (χ2) tests followed by 2 × 2 χ2 tests for post hoc pair-wise comparisons when the 2 × 3 results were significant. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 21.

Diagnosing Alzheimer"s: How Alzheimer"s is diagnosedTo diagnose Alzheimer"s dementia, doctors conduct tests to assess memory impairment and other thinking skills, judge functional abilities, and identify behavior changes. They also perform a series of tests to rule out other possible causes of impairment.By Mayo Clinic Staff

It"s important to get an accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer"s, the most common type of dementia. The correct diagnosis is an important first step toward getting the appropriate treatment, care, family education and plans for the future.

To diagnose Alzheimer"s dementia, your primary doctor, a doctor trained in brain conditions (neurologist) or a doctor trained to treat older adults (geriatrician) will review your symptoms, medical history, medication history and interview someone who knows you well such as a close friend or family member. Your doctor will also perform a physical examination and conduct several tests.

Doctors may order additional laboratory tests, brain-imaging tests or send you for detailed memory testing. These tests can provide doctors with useful information for diagnosis, including ruling out other conditions that cause similar symptoms.

Doctors will perform a physical evaluation and check that you don"t have other health conditions that could be causing or contributing to your symptoms, such as signs of past strokes, Parkinson"s disease, depression, sleep apnea or other medical conditions.

To assess your symptoms, your doctor may ask you to answer questions or perform tasks associated with your cognitive skills, such as your memory, abstract thinking, problem-solving, language usage and related skills.

Mental status testing. Your doctor may conduct mental status tests to test your thinking (cognitive) and memory skills. Doctors use the scores on these tests to evaluate your degree of cognitive impairment.

Neuropsychological tests. You may be evaluated by a specialist trained in brain conditions and mental health conditions (neuropsychologist). The evaluation can include extensive tests to evaluate your memory and thinking (cognitive) skills.

These tests help doctors determine if you have dementia, and if you"re able to safely conduct daily tasks such as taking medications as scheduled and managing your finances. They provide information on what you can still do as well as what you may have lost. These tests can also evaluate if depression may be causing your symptoms.

Doctors look for details that don"t fit with your former level of function. Your family member or friend often can explain how your thinking (cognitive) skills, functional abilities and behaviors have changed over time.

This series of clinical assessments, the physical exam and the setting (age and duration of progressive symptoms) often provide doctors with enough information to make a diagnosis of Alzheimer"s dementia. However, when the diagnosis isn"t clear, doctors may need to order additional tests.

Researchers are working on new ways to diagnose Alzheimer"s dementia earlier. New tests might be able to diagnose the disease when symptoms are very mild or even before symptoms start. Currently, researchers are developing tests that measure amyloid or tau in the blood. These tests are promising and may be used to determine who is at risk of Alzheimer"s dementia, and whether Alzheimer"s is the cause of one"s dementia.

You may feel nervous about seeing a health care provider when you or a family member has memory problems. Some people hide their symptoms, or family members cover for them. It can be difficult to deal with the losses that Alzheimer"s dementia can bring. These can include losing independence and driving abilities.

While there"s no cure for Alzheimer"s, an early diagnosis can still be helpful. Knowing what you can do is just as important as knowing what you can"t do. If another treatable condition is causing the memory problems, health care providers can start treatments.

For those with Alzheimer"s dementia, doctors can offer drug and nondrug interventions to manage symptoms. Doctors often prescribe drugs that may slow the decline in memory and other cognitive skills. You may also be able to participate in clinical trials.

An early diagnosis also helps you, your family and caregivers plan for the future. You"ll have the chance to make informed decisions on a number of issues, such as:

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

Medical tests for diagnosing Alzheimer"s. Alzheimer"s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/diagnosis/medical_tests. Accessed March 17, 2022.

The technology reads out loud what is on the screen and users can adapt them to their needs, for example you can decrease the speed of speech or change the language. Screen readers allow people to navigate through websites and applications via the speech output. Some screen readers can also be used with a Braille display.

When starting out with a screen reader, you need to learn some shortcut keys or touch gestures. While it is possible to master the basic interaction after learning just a few commands, becoming an advanced user able to interact confidently does require a bit of time and effort to get familiar with their advanced features. Training can help.

There are different screen readers available. Nearly all computers, tablets and smartphones have a screen reader function built in. The most popular programs are JAWS and NVDA for Windows computers, VoiceOver for the Mac and iPhone, and TalkBack on Android. The best choice for you depends on:The type of computer and or mobile phone that you have.

JAWS (Job Access With Speech) is a desktop screen reader for Windows and works well with Internet Explorer, Chrome or FireFox browsers. Jaws was one of the first screen readers and was launched for Windows 1.0 in 1995. Jaws is extremely popular and, as it can be scripted to work with applications, is widely used in the workplace. This is a paid-for screen reader but you can download a JAWS trial which will run for 40 minutes.

NVDA (Non Visual Desktop Access) is a free, open source screen reader for Windows computers. It is the second most used desktop screen reader and, like Jaws, also works well with all popular browsers. Being a free, very proficient screen reader on the web, NVDA has become increasingly popular as apps move into the browser. Download NVDA.

Narrator is the screen reader built into Windows. This works well with Microsoft Office and the Edge Browser. Press the Windows Logo key + Control + Enter to turn Narrator on and off (Windows Logo key + Enter for Windows 10 versions older than 1903 – released in the spring of 2018). The Microsoft training guide for narrator can be found on their website. While Narrator has a low up-take historically, there has been considerable development in recent months and, since the spring 2019 update to Windows 10, is now a very viable screen reader.

VoiceOveris the screen reader for Apple devices; Mac computers, iPads, iPhones, the Apple Watch and the Apple TV. It is particularly popular on the iPhone – working well with millions of apps and the internet (using Apple’s Safari browser). You don’t need to do anything to install VoiceOver. On your Apple device, simply go to settings and click or tap on Accessibility to find VoiceOver and a wealth of other powerful options.

TalkBack is also a very widely used screen reader. Found on Android devices, it works well with the majority of apps and the internet (Chrome being the default browser). No download is required on most Android devices – although on some it must be installed from the Google Play Store. To enable TalkBack, go to settings and tap on Accessibility (note that on some models of phone it may instead be called VoiceAssistantorAccessibility Suite). Performance of TalkBackcan vary between manufacturers - with best performance on those phones from Google and Samsung.

Other screen readers include SuperNova, System Access and Thunder. There is also an excellent screen reader built into Chromebooks called ChromeVox. We are not, however, including more information on these here.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey