a-si active matrix tft lcd h-ips free sample

TT169RAN11A is a color-active matrix LCD touch module, which includes amorphous silicon TFT (thin-film transistor) It is composed of a color TFT-LCD panel, driver IC, FPC, and a backlight unit. The module display area contains 240X280 pixels and can display up to 262K colors. This product accords with RoHS environmental criteria.

Display model TT085RAN10A is a color-active matrix thin-film transistor(TFT)liquid crystal display(LCD)that uses amorphous silicon TFT as a switching device. This TFT LCD has a 0.85 inch diagonally measured active display area with (128 horizontal by 128vertical pixels)resolution. This module is composed of a TFT LCD Panel, driver ICs, FPC and a Backlight unit.

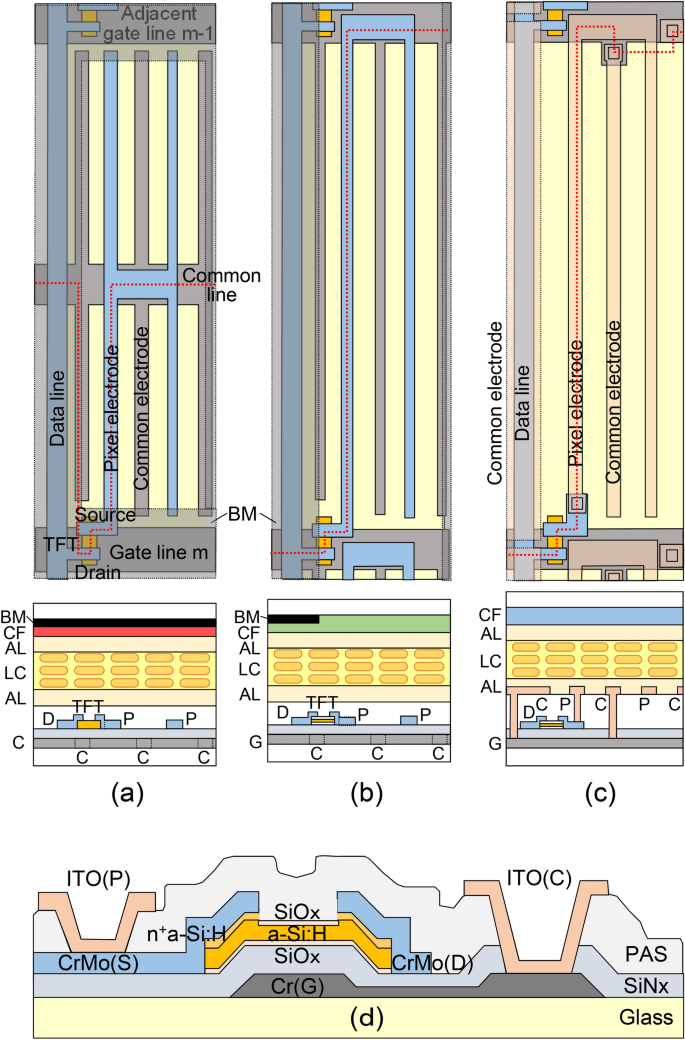

IPS (In-Plane Switching) lcd is still a type of TFT LCD, IPS TFT is also called SFT LCD (supper fine tft ),different to regular tft in TN (Twisted Nematic) mode, theIPS LCD liquid crystal elements inside the tft lcd cell, they are arrayed in plane inside the lcd cell when power off, so the light can not transmit it via theIPS lcdwhen power off, When power on, the liquid crystal elements inside the IPS tft would switch in a small angle, then the light would go through the IPS lcd display, then the display on since light go through the IPS display, the switching angle is related to the input power, the switch angle is related to the input power value of IPS LCD, the more switch angle, the more light would transmit the IPS LCD, we call it negative display mode.

The regular tft lcd, it is a-si TN (Twisted Nematic) tft lcd, its liquid crystal elements are arrayed in vertical type, the light could transmit the regularTFT LCDwhen power off. When power on, the liquid crystal twist in some angle, then it block the light transmit the tft lcd, then make the display elements display on by this way, the liquid crystal twist angle is also related to the input power, the more twist angle, the more light would be blocked by the tft lcd, it is tft lcd working mode.

A TFT lcd display is vivid and colorful than a common monochrome lcd display. TFT refreshes more quickly response than a monochrome LCD display and shows motion more smoothly. TFT displays use more electricity in driving than monochrome LCD screens, so they not only cost more in the first place, but they are also more expensive to drive tft lcd screen.The two most common types of TFT LCDs are IPS and TN displays.

This type is a 10.25 inch TFT LCD module, with a backlight unit, 2-port LVDS interface (DE Mode), with a control board, the resolution of this type is 1920*3(RGB)*720. This product accords with RoHS.

Shenzhen SLS Industrial Co.,ltd established in 2003, is a professional LCD module manufacturer and solution provider. We have 1 full-auto COG assembly line, 2 semi-auto assembly line, backlight assembly line, no dust TP bonding line and manufacturing tech support, we can provide unique, innovative and cost effective LCD module development and manufacturing. Our product range includes: middle-small size TFT LCD, industrial capacitive touch panel... Our LCD products have been widely used in communications, GPS, Equipment, electronic audio-visual, instrumentation, household appliances, PDA and other industries.

A thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD) is a variant of a liquid-crystal display that uses thin-film-transistor technologyactive matrix LCD, in contrast to passive matrix LCDs or simple, direct-driven (i.e. with segments directly connected to electronics outside the LCD) LCDs with a few segments.

In February 1957, John Wallmark of RCA filed a patent for a thin film MOSFET. Paul K. Weimer, also of RCA implemented Wallmark"s ideas and developed the thin-film transistor (TFT) in 1962, a type of MOSFET distinct from the standard bulk MOSFET. It was made with thin films of cadmium selenide and cadmium sulfide. The idea of a TFT-based liquid-crystal display (LCD) was conceived by Bernard Lechner of RCA Laboratories in 1968. In 1971, Lechner, F. J. Marlowe, E. O. Nester and J. Tults demonstrated a 2-by-18 matrix display driven by a hybrid circuit using the dynamic scattering mode of LCDs.T. Peter Brody, J. A. Asars and G. D. Dixon at Westinghouse Research Laboratories developed a CdSe (cadmium selenide) TFT, which they used to demonstrate the first CdSe thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD).active-matrix liquid-crystal display (AM LCD) using CdSe TFTs in 1974, and then Brody coined the term "active matrix" in 1975.high-resolution and high-quality electronic visual display devices use TFT-based active matrix displays.

The circuit layout process of a TFT-LCD is very similar to that of semiconductor products. However, rather than fabricating the transistors from silicon, that is formed into a crystalline silicon wafer, they are made from a thin film of amorphous silicon that is deposited on a glass panel. The silicon layer for TFT-LCDs is typically deposited using the PECVD process.

Polycrystalline silicon is sometimes used in displays requiring higher TFT performance. Examples include small high-resolution displays such as those found in projectors or viewfinders. Amorphous silicon-based TFTs are by far the most common, due to their lower production cost, whereas polycrystalline silicon TFTs are more costly and much more difficult to produce.

The twisted nematic display is one of the oldest and frequently cheapest kind of LCD display technologies available. TN displays benefit from fast pixel response times and less smearing than other LCD display technology, but suffer from poor color reproduction and limited viewing angles, especially in the vertical direction. Colors will shift, potentially to the point of completely inverting, when viewed at an angle that is not perpendicular to the display. Modern, high end consumer products have developed methods to overcome the technology"s shortcomings, such as RTC (Response Time Compensation / Overdrive) technologies. Modern TN displays can look significantly better than older TN displays from decades earlier, but overall TN has inferior viewing angles and poor color in comparison to other technology.

The transmittance of a pixel of an LCD panel typically does not change linearly with the applied voltage,sRGB standard for computer monitors requires a specific nonlinear dependence of the amount of emitted light as a function of the RGB value.

Less expensive PVA panels often use dithering and FRC, whereas super-PVA (S-PVA) panels all use at least 8 bits per color component and do not use color simulation methods.BRAVIA LCD TVs offer 10-bit and xvYCC color support, for example, the Bravia X4500 series. S-PVA also offers fast response times using modern RTC technologies.

TFT dual-transistor pixel or cell technology is a reflective-display technology for use in very-low-power-consumption applications such as electronic shelf labels (ESL), digital watches, or metering. DTP involves adding a secondary transistor gate in the single TFT cell to maintain the display of a pixel during a period of 1s without loss of image or without degrading the TFT transistors over time. By slowing the refresh rate of the standard frequency from 60 Hz to 1 Hz, DTP claims to increase the power efficiency by multiple orders of magnitude.

Due to the very high cost of building TFT factories, there are few major OEM panel vendors for large display panels. The glass panel suppliers are as follows:

External consumer display devices like a TFT LCD feature one or more analog VGA, DVI, HDMI, or DisplayPort interface, with many featuring a selection of these interfaces. Inside external display devices there is a controller board that will convert the video signal using color mapping and image scaling usually employing the discrete cosine transform (DCT) in order to convert any video source like CVBS, VGA, DVI, HDMI, etc. into digital RGB at the native resolution of the display panel. In a laptop the graphics chip will directly produce a signal suitable for connection to the built-in TFT display. A control mechanism for the backlight is usually included on the same controller board.

The low level interface of STN, DSTN, or TFT display panels use either single ended TTL 5 V signal for older displays or TTL 3.3 V for slightly newer displays that transmits the pixel clock, horizontal sync, vertical sync, digital red, digital green, digital blue in parallel. Some models (for example the AT070TN92) also feature input/display enable, horizontal scan direction and vertical scan direction signals.

New and large (>15") TFT displays often use LVDS signaling that transmits the same contents as the parallel interface (Hsync, Vsync, RGB) but will put control and RGB bits into a number of serial transmission lines synchronized to a clock whose rate is equal to the pixel rate. LVDS transmits seven bits per clock per data line, with six bits being data and one bit used to signal if the other six bits need to be inverted in order to maintain DC balance. Low-cost TFT displays often have three data lines and therefore only directly support 18 bits per pixel. Upscale displays have four or five data lines to support 24 bits per pixel (truecolor) or 30 bits per pixel respectively. Panel manufacturers are slowly replacing LVDS with Internal DisplayPort and Embedded DisplayPort, which allow sixfold reduction of the number of differential pairs.

Backlight intensity is usually controlled by varying a few volts DC, or generating a PWM signal, or adjusting a potentiometer or simply fixed. This in turn controls a high-voltage (1.3 kV) DC-AC inverter or a matrix of LEDs. The method to control the intensity of LED is to pulse them with PWM which can be source of harmonic flicker.

The bare display panel will only accept a digital video signal at the resolution determined by the panel pixel matrix designed at manufacture. Some screen panels will ignore the LSB bits of the color information to present a consistent interface (8 bit -> 6 bit/color x3).

Kawamoto, H. (2012). "The Inventors of TFT Active-Matrix LCD Receive the 2011 IEEE Nishizawa Medal". Journal of Display Technology. 8 (1): 3–4. Bibcode:2012JDisT...8....3K. doi:10.1109/JDT.2011.2177740. ISSN 1551-319X.

K. H. Lee; H. Y. Kim; K. H. Park; S. J. Jang; I. C. Park & J. Y. Lee (June 2006). "A Novel Outdoor Readability of Portable TFT-LCD with AFFS Technology". SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers. AIP. 37 (1): 1079–82. doi:10.1889/1.2433159. S2CID 129569963.

From the MOSFET, the TFT was born. The TFT varies from standard MOSFETs, or bulk MOSFETs, because, as the name implies, it uses thin films. The TFT began a new era of electronics. In 1968, just six years after the first TFT development, Bernard J. Lechner of RCA shared his idea of the TFT Liquid Crystal Display (LCD), something that would boom in popularity in our modern times. The TFT LCD was then first created in 1973 at the Westinghouse Research Laboratories. These LCDs were composed of pixels controlled by transistors. In FETs, substrates were just the semiconductor material, but in manufacturing TFT LCDs, glass substrates were used so that the pixels could be displayed.

But that was not the end of TFT developments. Soon after, in 1974, T. Peter Brody, one of the developers of the TFT LCD, and Fang-Chen Luo created the first active-matrix LCD (AM LCD). An active matrix controls each pixel individually, meaning that each pixel’s respective TFT had its signal actively preserved. This opened doors to better performance and speed as displays became more complex.

Though TFTs can use a variety of materials for their semiconductor layers, silicon has become the most popular, creating the silicon-based TFT, abbreviated as Si TFT. As a semiconductor device, the TFT, as well as all FETs, use solid-state electronics, meaning that electricity flows through the structure of the semiconductor layer rather than vacuum tubes.

Due to the variety in silicon’s possible structures, the Si TFT’s characteristics can vary as well. The most common form is amorphous silicon (A-Si), which is deposited during the first step of the semiconductor fabrication process onto the substrate in low temperatures. It is most usable when hydrogenated into the form A-Si:H. This then significantly alters the properties of A-Si; without the hydrogen, the material struggles with doping (the introduction of impurities to increase mobility of charges); in the form A-Si:H, however, the semiconductor layer becomes much more photoconductive and dopable. The A-Si:H TFT was first developed in 1979 which is stable at room temperature and became the best option for AM LCDs which consequently began rising in popularity after this breakthrough.

A second potential form of silicon is the microcrystalline silicon. Though it retains a similar form to A-Si, this type of silicon also has grains of what is known as crystalline structures. Amorphous structures have a more random, less geometric shape to their network-like structures, but crystalline, on the other hand, is more structured and organized. If grown correctly, microcrystalline silicon has better electron mobility than A-Si:H and greater stability too, as it has less hydrogen within its structure. It is deposited in a similar fashion to A-Si’s deposition.

And lastly, there is polycrystalline silicon, also known as polysilicon and poly-Si. Microcrystalline silicon is the middle between A-Si and poly-Si since poly-Si’s structure is composed of many crystallites. This specific form is made by annealing the silicon material which means adding heat to alter the properties of the structure. With poly-Si, the atoms in the crystal lattice shift and move when heated, and when cooled, the structure recrystallizes.

The biggest difference between these forms, notably A-Si and poly-Si, is that charge carriers are much more mobile and the material is much more stable when it comes to using poly-Si over A-Si. When creating complicated and high-speed TFT-based displays, poly-Si’s characteristics allow for this. Yet, A-Si is still very important due to its low-leakage nature, meaning that leakage current is not lost as heavily when a dielectric insulator is not totally non-conductive.

As TFTs began to increase their presence in display technology, transparent semiconductors and electrodes became more appealing to the manufacturers. Indium tin oxide (ITO) is an example of a popular transparent oxide used for its appearance, good conductivity, and ease of deposition.

Research of the TFT with different materials has led to the application of threshold voltage, or how much voltage is needed to turn on the device. This value is greatly dependent on thickness and choice of the oxide. When it comes to the oxide, this relates back to the idea of leakage current. With thinner layers and certain types of oxide, the leakage current may be greater, but this in turn could lower threshold voltage, as leakage into the device will also increase. In order to tap into the TFT’s potential for low power consumption, the lower the threshold voltage, the better the device’s appeal.

Another branch of development that stemmed from the TFT is that of organic TFTs (OTFT). First created in 1986, OTFTs usually use solution-casting of polymers, or macromolecules. This device made people hesitant, as it tended to have a slow carrier mobility, meaning slow response times. However, researchers have carried out experimentation with the OTFT because it has potential to be applied to displays different from those that traditional TFTs are used for, such as flexible, plastic displays. This research still continues today. With its simpler processing than traditional silicon technology, the OTFT holds much potential for modern day and future technologies.

As the key component behind liquid crystal displays (LCD), these materials change light polarization to create vibrant, high-resolution images on digital screens. The growth of LCD technology has helped propel the larger display panel market enormously, with industry valuation projected to reach $178.20 billion by 2026.

A prolific variety of LCD types has been developed to best meet their exact use-cases and end-environments. Displays may be optimized for power consumption, contrast ratio, color reproduction, optimal viewing angle, temperature range, cost, and more.

Passive Matrix LCDs are addressed with common and segment electrodes. A pixel or an icon is formed at the intersection where a common and a segment electrode overlap. Common electrodes are addressed one-at-a-time in a sequence. Segment electrodes are addressed simultaneously with the information corresponding to all pixels or icons connected to the current common electrode. This method is referred to as multiplexing.

Passive Matrix LCDs offer a cost advantage (both parts and tooling) and are highly customizable. The counterpart to Passive Matrix displays are Active Matrix displays.

Active-Matrix LCDs were developed to overcome some of the limitations of Passive Matrix LCDs – namely resolution, color, and size. Within an Active-Matrix LCD, an “active element” is added to each pixel location (the intersection between a horizontal row and vertical column electrode). These active elements, which can be diodes or transistors, create a threshold and allow control of the optical response of the liquid crystal structure to the applied voltage. Transistors are used as switches to charge a capacitor, which then provides the voltage to the pixel. Whenever a row is turned on, one at a time, all transistor switches in that row are closed and all pixel capacitors are charged with the appropriate voltage. The capacitor then keeps the voltage applied to the pixel after the row is switched off until the next refresh cycle.

Furthermore, the processes used for manufacturing Active-Matrix LCDs can create much finer details on the electrode structure. This allows splitting each pixel in three sub-pixels with different color. This together with the better voltage control allows full color displays.

The transistor switches used in Active Matrix Displays must not protrude significantly above the surface of the display substrates lest they might interfere with a uniform liquid crystal layer thickness. They must be implemented in thin films of suitable materials. Hence, the name Thin Film Transistors (TFT). While AM and TFT have a different meaning, they are often used interchangeably to indicate a higher performance display.

TFTs can be formed by amorphous silicon (denoted α-Si TFT), by poly-crystalline silicon (LTPS for Low Temperature Poly Silicon), or by semiconducting metal oxides (Ox-TFT or IGZO-TFT for Indium Gallium Zinc Oxide).

Currently the most common Electronics Display Technology on the market is LCD technology and among LCD technologies, TFT display technology is the most widely used across consumer applications (laptops, tablets, TVs, Mobile phones, etc.) as well as many industrial, automotive, and medical applications.

As the first commercially successful LCD technology, Passive Matrix Twisted Nematic (TN) LCDs use a 90° twist of the nematic LC fluid between two polarizers to display information. The twist of the LC fluid either blocks light from passing through the LCD cell or allows light to pass, depending on the applied voltage. The applied voltage changes the twisted nematic orientation into an orientation that does not change the polarization of tight. This is called the TN effect.

Initially, Passive TN LCDs were used in segmented, icon, or character displays where an image element was turned “on” and “off” depending on how the fluid was driven. Improvements were made along the way to address the limited viewing angle of TN technology, which can suffer from contrast loss or even inversion at shallow angles.

The numbers of rows or icons that can be addressed in a TN display without Active Matrix addressing is very limited. This is related to how strongly the liquid crystal responds to the applied voltage. Twisting the LC nematic fluid more than 180 degrees (typically between 210 and 270 degrees) causes the display to require a much smaller voltage difference between on and off pixels. This in turn allows addressing of many more rows without an active matrix. Displays with a twist between 210 and 270 degrees are called Super Twisted Nematic displays.

The birefringence of an STN display can be approximated with a stretched transparent plastic film. Adding such a film to an STN display instead of the 2nd STN display is a lot more attractive and has almost the same performance. This is referred to as a Film Compensated STN display (FSTN, or sometimes if two films are used as FFSTN).

The advantage of these technologies is a much wider and more symmetrical viewing angle along with the elimination of the contrast inversion (or color shift) seen in TN TFT LCDs when viewed from various angles. IPS and FFS displays also are less sensitive to pressure, which is a big advantage in touchscreen displays.

Throughout the development of these technologies, there were the initial type, super, advanced, pro, etc. versions, which led to a lot of acronyms like (S-IPS, AS-IPS, H-IPS, FFS-Pro)

Legacy LCDs normally have the driver ICs (integrated circuit) mounted on a printed circuit board (PCBA) which consists of a flat sheet of insulating material used to mount and connect the driver IC and electronic periphery to the LCD. PCBs can be a single-sided, double-sided or multi-layer.

TN Film panels are the mostly widely used in the desktop display market and have been for many years since LCD monitors became mainstream. Smaller sized screens (15″, 17″ and 19″) are almost exclusively limited to this technology in fact and it has also extended into larger screen sizes over the last 7 years or so, now being a popular choice in the 20 – 28″ bracket as well. The TN Film panels are made by many different manufacturers, with the big names all having a share in the market (Samsung, LG.Display, AU Optronics) and being backed up by the other companies including most notably Innolux and Chunghwa Picture Tubes (CPT). You may see different generations of TN Film being discussed, but over the years the performance characteristics have remained similar overall.

The other main reason for using TN Film is that it is fundamentally a responsive technology in terms of pixel latency, something which has always been a key consideration for LCD buyers. It has long been the choice for gaming screens and response times have long been, and still are today, the lowest out of all the technologies overall. Response times typically reach a limit of around 5ms at the ISO quoted black > white > black transition, and as low as 1ms across grey to grey transitions where Response Time Compensation (overdrive) is used. TN Film has also been incorporated into true 120Hz+ refresh rate desktop displays, pairing low response times with high refresh rates for even better moving picture and gaming experiences, improved frame rates and adding 3D stereoscopic content support. Modern 120Hz+ refresh rate screens normally also support NVIDIA 3D Vision 2 and their LightBoost system which brings about another advantage for gaming. You can use the LightBoost strobed backlight system in 2D gaming to greatly reduce the perceived motion blur which is a significant benefit. Some screens even include a native blur reduction mode instead of having to rely on LightBoost ‘hacks’, providing better support for strobing backlights and improving gaming experiences when it comes to perceived motion blur. As a result, TN Film is still the choice for gamer screens because of the low response times and 120Hz+ refresh rate support.

In MVA panels, the crystals in the domains are oriented differently, so if one domain lets light pass through, the neighboring domain will have the crystals at an angle and will shutter the light (of course, save for the display of white color, in which case all the crystals are placed almost in parallel to the matrix plane).

AU Optronics have more recently (around 2005) been working on their latest generation of MVA panel technology, termed ‘Advanced Multi Domain Vertical Alignment’ (AMVA). This is still produced today although a lot of their focus has moved to the similarly named, and not to be confused AHVA (Advanced Hyper Viewing Angle, IPS-type) technology. Compared with older MVA generations, AMVA is designed to offer improved performance including reduced colour washout, and the aim to conquer the significant problem of colour distortion with traditional wide viewing angle technology. This technology creates more domains than conventional multi-domain vertical alignment (MVA) LCD’s and reduces the variation of transmittance in oblique angles. It helps improve colour washout and provides better image quality in oblique angles than conventional VA LCD’s. Also, it has been widely recognized worldwide that AMVA technology is one of the few ways to provide optimized image quality through multiple domains.

We have included this technology in this section as it is a modern technology still produced by Sharp as opposed to the older generations of MVA discussed above. Sharp are not a major panel manufacturer in the desktop space, but during 2013 began to invest in new and interesting panels using their MVA technology. Of note is their 23.5″ sized MVA panel which was used in the Eizo Foris FG2421 display. This is the first MVA panel to offer a native 120Hz refresh rate, making it an attractive option for gamers. Response times had been boosted significantly on the most part, bringing this MVA technology in line with modern IPS-type panels when it comes to pixel latency. The 120Hz support finally allowed for improved frame rates and motion smoothness from VA technology, helping to rival the wide range of 120Hz+ TN Film panels on the market.

Of particular note also are the excellent contrast ratios of this technology, reaching up to an excellent 5000:1 in practice, not just on paper. Viewing angles are certainly better than TN Film and so overall these MVA panels can offer an attractive all-round option for gaming, without some of the draw-backs of the TN Film panels. Viewing angles are not as wide as IPS panel types and there is still some noticeable gamma shift at wider angles, and the characteristic VA off-centre contrast shift still exists.

The liquid crystals in a PVA matrix have the same structure as in a MVA matrix – domains with varying orientation of the crystals allow keeping the same color, almost irrespective of the user’s line of sight and viewing angle. Viewing angles are not perfect though, as like with MVA matrices when you are looking straight at the screen, the matrix “loses” some shades, which return after you deflect your line of sight from the perpendicular a little. This ‘off-centre’ contrast shift, or ‘black crush’ as it is sometimes called is the reason why some colour enthusiasts prefer IPS-type displays. The overall viewing angles are also not as wide as IPS-type panels, showing more obvious colour and contrast shifts as you change your line or sight.

Close up inspection of the pixels making up an S-PVA matrix reveals the above. The dual sub-pixels consist of two zones, A and B, with one being turned on only at high brightness. So, the first picture shows red sub-pixels of roughly rectangular shape while the second picture shows two small pieces that represent one zone of each sub-pixel, the second zone being completely turned off.

It is this two-zone structure that differentiates S-PVA from older PVA matrixes which used to have a monolithic sub-pixel divided into four domains. An S-PVA matrix has two zones with four domains in each, for a total of eight domains per each sub-pixel. This helps fight the gamma shift effect which occurs when not only the contrast ratio but also the gamma (i.e. the correlation between the video signal sent to the monitor and the resulting screen brightness) changes when the screen is viewed from a side. The pixel zones of S-PVA matrixes have such shape, position and voltage (in the most expensive matrixes that are installed into some TV-sets, the two zones of one sub-pixel can even be controlled independently) as to mutually compensate the gamma shift effect for each other. Unfortunately, the gamma shift effect is not absolutely eliminated even in S-PVA matrixes. Besides, these matrixes have one more difference from PVA. Their viewing angles are asymmetric: the gamma shift is bigger from one side.

There is very little official information about this technology but some Samsung monitors started to be labelled as having an A-PVA panel around 2012 onwards. We suspect that nothing has really changed from S-PVA / cPVA panels, but that the term “Advanced” has been added in to try and distinguish the new models, and perhaps compete with LG.Display’s successful IPS technology and AU Optronics AMVA technology where they have also added the word “Advanced” for their latest generations (see AMVA and AH-IPS).

In Plane Switching (IPS – also known as ‘Super TFT’) technology was developed by Hitachi in 1996 to try and solve the two main limitations of TN Film matrices at the time, those being small viewing angles and low-quality color reproduction. The name In-Plane Switching comes from the crystals in the cells of the IPS panel lying always in the same plane and being always parallel to the panel’s plane (if we don’t take into account the minor interference from the electrodes). When voltage is applied to a cell, the crystals of that cell all make a 90-degrees turn. By the way, an IPS panel lets the backlight pass through in its active state and shutters it in its passive state (when no voltage is applied), so if a thin-film transistor crashes, the corresponding pixel will always remain black, unlike with TN matrices.

IPS matrices differ from TN Film panels not only in the structure of the crystals, but also in the placement of the electrodes – both electrodes are on one wafer and take more space than electrodes of TN matrices. This leads to a lower contrast and brightness of the matrix. IPS was adopted for colour professional displays due to its wide viewing angles, good colour reproduction and stable image quality. However, response times were very slow originally, making IPS unsuitable for dynamic content.

In 1998 production started for Super-IPS panels, and were mostly produced by LG.Philips (now LG.Display). They have gone through several generations since their inception. Initially S-IPS built upon the strengths of IPS by employing an advanced “multi-domain” liquid crystal alignmentt. The term S-IPS is actually still widely used in modern screens, but technically there may be subtle differences making them S-IPS, e-IPS, H-IPS, or p-IPS (etc) generations for example. See the following sections for more information.

Since their initial production in 1998 S-IPS panels have gained the widest recognition, mostly due to the efforts of LG.Philips LCD (now known as LG.Display), who were outputting rather inexpensive and high-quality 19″ – 30″ matrices. The response time was among the serious drawbacks of the IPS technology – first panels were as slow as 60ms on the “official” black-to-white-to-back transitions (and even slower on grey-to-grey ones!) Fortunately, the engineers dragged the full response time down to 25 ms and then 16ms later, and this total is equally divided between pixel rise and pixel fall times. Moreover, the response time doesn’t greatly grow up on black-to-gray transitions compared to the specification, so some older S-IPS matrices at the time could challenge TN Film panels in this parameter.

In 2006 – 2007 LG.Display IPS panels have altered the pixel layout giving rise to ‘Horizontal-IPS’ (H-IPS) panels. In simple terms, the manufacturer has reportedly reduced the electrode width to reduce light leakage, and this has in turn created a new pixel structure. This structure features vertically aligned sub-pixels in straight lines as opposed to the arrow shape of older S-IPS panels.

In practice, it can be quite hard to spot the difference, but close examination can reveal a less ‘sparkly’ appearance and a slightly improved contrast ratio. Some users find a difference in text appearance as well relating to this new pixel structure but text remains clear and sharp. H-IPS will also often show a white glow from a wide angle when viewing black images, as opposed to the purple tint from S-IPS matrices. This is actually more noticeable than the S-IPS purple tint and is referred to as “IPS glow”. Some IPS panels in high end displays are coupled with an Advanced True Wide (A-TW) polarizer which helps improve blacks from wide viewing angles, and reduces some of the pale glow you can normally see. However, this A-TW polarizer is not included in every model featuring H-IPS and this should not be confused. It is very rarely used nowadays unfortunately. H-IPS panels from around this time are sometimes criticized for their Anti-Glare (AG) coating, which can appear quite grainy and dirty looking, especially when viewing white backgrounds in office applications.

Close inspection of modern IPS panels can show this new H-IPS pixel structure, although not all manufacturers refer to their models as featuring an H-IPS panel. Indeed, LG.Display don’t really make reference to this H-IPS version, although from a technical point of view, most modern IPS panels are H-IPS in format. As an example of someone who has referred to this new generation, NEC have used the H-IPS name in their panel specs for models such as the LCD2690WXUi2 and LCD3090WUXi screens.

The following technical report has feedback from the LG.Philips LCD laboratory workers: “Wedesigned a new pixel layout to improve the aperture ratioof IPS mode TFT-LCD (H-IPS). This H-IPS pixel layout design has reducedthe width of side common electrode used to minimize thecross talk and light leakage which is induced by interferencebetween data bus line and side common electrode of conventionalIPS mode. The side common electrodes of a pixel canbe reduced by horizontal layout of inter-digital electrode pattern whereconventional IPS pixel designs have vertical layout of inter-digital electrodes.We realized 15 inch XGA TFT LCD of H-IPS structurewhich has aperture ratio as much as 1.2 times ofcorresponding conventional IPS pixel design.” ©2004 Society for Information Display.

During 2009 LG.Display began to develop a new generation of e-IPS (it is unclear what the “e” actually stands for) panels which is a sub-category of H-IPS. They simplified the sub-pixel structure in comparison with H-IPS (similar to cPVA vs. S-PVA) and increased the transparency of the matrix by producing a wider aperture for light transmission. In doing so, they have managed to reduce production costs significantly by integrating the panels with lower cost, lower power backlight units. This allowed LG.Display to compete with the low cost TN Film panels and Samsung’s new cPVA generation. Because transparency is increased, they are able to reduce backlight intensity as you need less light to achieve the same luminance now.

The drawback of e-IPS in comparison with S-IPS is that the viewing angles are slightly smaller. When you take a look at an e-IPS matrix from a side, the image will lose its contrast as black turns into grey. On the other hand, there is no tonal shift (as with TN and cPVA matrixes) and the viewing angles, especially vertical ones, are still much larger than with TN Film. Many e-IPS panels are actually 6-bit + AFRC modules (as opposed to true 8-bit) which might explain how the costs are kept very low in some cases, although in practice the FRC algorithm is very well implemented and you are unlikely to see any obvious side affects. Like H-IPS panels from years prior, e-IPS panels are sometimes criticized for their Anti-Glare (AG) coating, which can appear quite grainy and dirty looking, especially when viewing white backgrounds in office applications.

These are new names which some manufacturers seem to promote a little around 2009 – 2010. It has been stated that these ‘new’ panels offer improved energy efficiency, but it’s unclear what the new letters stand for. Perhaps the ‘UH-IPS’ stands for ‘Ultra Horizontal-IPS’? It certainly seems these are just slightly updated versions of H-IPS panels as was e-IPS. It’s possible as well that UH-IPS is just the same thing as e-IPS, with different manufacturers using different terminology to try and separate their displays. We suspect that UH-IPS is either the same thing as e-IPS, or a sub-category of that development, which in turn is a sub-category of H-IPS.

Some spec sheets from LG.Display give some clues as to the differences. The lines separating the sub-pixels are smaller than with H-IPS and therefore the UH-IPS technology has an 18% higher aperture ratio. The drive for increased LCD panel transmissivity is not for the purpose specifically of increasing on screen brightness, but rather to maintain brightness and reduce backlight lamps, inverters, and optical films in order to lower panel costs. LG have used this terminology with some of their LED backlight monitors.

Another term used by some manufacturers around 2010 with the launch of their IPS screens. This “S-IPS II” reportedly has an even higher aperture ratio than UH-IPS (11.6% higher), further improving brightness and contrast and helping save energy. It looks also from the information available (above) that the pixel structure has been altered and is no longer vertical as with H-IPS, but more like the traditional S-IPS / AS-IPS “arrow” layout. This looks more like an e-IPS type development, but returning to the older S-IPS pixel layout as opposed to developing H-IPS.

This was a new name which NEC introduced in early 2010 with their new PA series of screens. Thankfully they’ve been kind enough to tell us what the ‘p’ stands for in their marketing, giving rise to the generation of ‘Performance IPS’ panels. This new panel name is being used in the new 24″ – 30″ sized screens (PA241W, PA271W and PA301W). In fact the p-IPS name is just a sub-category of H-IPS technology, being created as a way for NEC to distinguish their new “10-bit” models from the rest of their range. In addition, when you look into the details of it the panels are actually an 8-bit module with 10-bit receiver, giving you an 8-bit + FRC module. This is capable of producing a 1.07 billion colour palette (10-bit) through FRC technology but it is not a true 10-bit colour depth.

This term was introduced by LG.Display in 2011 and primarily used when talking about their smaller panels, used in tablets and mobile devices. The term “Retina” (introduced by Apple) has also been used to describe these new panels, offering increased resolution and PPI. That seemed to be the main focus of AH-IPS panels when first introduced although they also offered an increased aperture size, allowing for greater light transmission and lower power consumption as a result. In the desktop monitor market the term “AH-IPS” has been used by several manufacturers in an effort to try and distinguish their new models, when in fact many could equally be described as H-IPS or e-IPS. With the high resolution aspect in mind, the modern 27″ 2560 x 1440 IPS panels could sensibly be referred to as AH-IPS and the term has been used for some of the very recent panels. In fact there have been a couple of other changes in IPS based screens at around the same time (2012) with the introduction of wide gamut GB-r-LED backlighting, and the change in the Anti-Glare (AG) coating being used. With older S-IPS / H-IPS panels often being criticised for their grainy AG coating, this new lighter coating offers improved picture quality and sharpness.

The term AH-IPS seems to be widely used now in 2014/2015 for modern IPS panels, and with the arrival of other ultra-high res panels we expect it to be used for some time. Performance characteristics remain very similar to older H-IPS and e-IPS panel generations overall. Response times are generally very good nowadays, with quoted specs as low as 5ms G2G common. They aren’t quite as fast as modern TN Film panels still in most cases. Only very recently (2015) have high refresh rate IPS-type panels been introduced, although not by LG.Display (see AHVA section). At the time of writing there is no native support for 120Hz+ refresh rates at this time from LG.Display manufactured IPS-variants. Some Korean manufactured displays featuring IPS panels are capable of being “over-clocked” to 100Hz+ but this is not officially supported by the panel, and can really vary from one screen to another. Furthermore, response times are not adequate to provide optimum gaming experience in most cases, despite the improved refresh rate.

Response times are very comparable to IPS matrices, with 5ms G2G being the current lowest spec on paper. There is currently no support for refresh rates above 60Hz from Samsung PLS panels, although there are some Korean manufactured screens which can be over-clocked to 100Hz refresh rates. This is not natively or officially supported though. Contrast ratios are typically around 700 – 900:1 in practice, although can reach up to 1000:1 in some cases as per their spec. Viewing angles are very comparable to IPS as well with wide fields of view and freedom from the off-centre contrast shifts you see from VA panels. From a wide angle dark content has a pale / white glow to it like modern IPS panels, again leading to a fair amount of so-called “PLS-glow” which can be distracting to some users. AG coating is also light, much like the light coating used on modern AH-IPS panels from LG.Display.

All in all, PLS is very comparable in practice to IPS. It should be noted that some display manufacturers market their screens as using an IPS panel, whereas underneath the hood the panel is actually a Samsung PLS matrix. Testament to how close these technologies are really considered although somewhat mis-leading. Samsung have largely moved away from their focus on PVA panels and are concentrating on PLS (and TN Film still) now instead. At the time of writing PLS panels are typically available in sizes between 23 and 27″ with resolutions up to 2560 x 1440. They do also have a 31.5″ panel with Ultra HD 3840 x 2160 available which is currently their largest. They do not currently manufacturer any ultra-wide 21:9 aspect ratio of curved format panels.

In 2012 some PLS based screens started to be marketed using the “AD-PLS” name. It is unclear what is supposed to have changed, if anything, with these recent panel variants. We suspect this is just a marketing name designed to keep up with LG.Display’s change to the “Advanced High-Performance IPS (AH-IPS)” name from the same time. Performance characteristics remain as described in the PLS section above.

Response time specs reach as low as 4ms G2G on paper but in reality the matrix does not perform any better than the faster IPS or PLS panel versions. Contrast ratios can reach up to the advertised 1000:1 and viewing angles are also very comparable to IPS. There is no off-centre contrast shift like you see on normal VA panels, but a pale glow is visible on dark content from an angle like with IPS/PLS. The AG coating is very light, often semi-glossy.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey