stm32 blue pill wires with 1.8 tft lcd display quotation

The Serial Peripheral Interface is a synchronous serial communication interface for short-distance communication, it is typically used in embedded systems. The interface was developed by Motorola in the mid 1980’s and has become a very popular standard.

It is used with many kinds of sensors, LCD’s and also SD-Cards. SPI operates in a Master-Slave model, with a possibility of multiple slave devices, each selected in turn by a SS (slave select) or CS (chip select) pin that is usually pulled low by the master.

You should also note the SPI slave devices that do not have a tri-state mode on their MISO pins, should not be used on the same bus as devices that have without using an external tri-state buffer circuit between the non-tristate device and the rest of the devices on the MISO bus.

To begin communication, the bus master configures the clock, using a frequency supported by the slave device, typically up to a few MHz. The master then selects the slave device with a logic level 0 on the select line. If a waiting period is required, such as for an analog-to-digital conversion, the master must wait for at least that period of time before issuing clock cycles.

Transmissions normally involve two shift registers of some given word-size, such as eight bits, one in the master and one in the slave; they are connected in a virtual ring topology. Data is usually shifted out with the most significant bit first. On the clock edge, both master and slave shift out a bit and output it on the transmission line to the counterpart. On the next clock edge, at each receiver the bit is sampled from the transmission line and set as a new least-significant bit of the shift register. After the register bits have been shifted out and in, the master and slave have exchanged register values. If more data needs to be exchanged, the shift registers are reloaded and the process repeats. Transmission may continue for any number of clock cycles. When complete, the master stops toggling the clock signal, and typically deselects the slave.

In addition to setting the clock frequency, the master must also configure the clock polarity and phase with respect to the data. Motorola SPI Block Guide names these two options as CPOL and CPHA (for clock polarity and phase) respectively, a convention most vendors have also adopted.

An alternative way of considering it is to say that a CPHA=0 cycle consists of a half cycle with the clock idle, followed by a half cycle with the clock asserted.

An alternative way of considering it is to say that a CPHA=1 cycle consists of a half cycle with the clock asserted, followed by a half cycle with the clock idle.

The combinations of polarity and phases are often referred to as modes which are commonly numbered according to the following convention, with CPOL as the high order bit and CPHA as the low order bit:

Note that in Full Duplex operation, the Master device could transmit and receive with different modes. For instance, it could transmit in Mode 0 and be receiving in Mode 1 at the same time.

Pull-up resistors between the power source and chip select lines are recommended for systems where the master’s chip select pins may default to an undefined state. When separate software routines initialize each chip select and communicate with its slave, pull-up resistors prevent other uninitialized slaves from responding.

Since the MISO pins of the slaves are connected together, they are required to be tri-state pins (high, low or high-impedance), where the high-impedance output must be applied when the slave is not selected. Slave devices not supporting tri-state may be used in independent slave configuration by adding a tri-state buffer chip controlled by the chip select signal. (Since only a single signal line needs to be tri-stated per slave, one typical standard logic chip that contains four tristate buffers with independent gate inputs can be used to interface up to four slave devices to an SPI bus.)

Some products that implement SPI may be connected in a daisy chain configuration, the first slave output being connected to the second slave input, etc. The SPI port of each slave is designed to send out during the second group of clock pulses an exact copy of the data it received during the first group of clock pulses. The whole chain acts as a communication shift register; daisy chaining is often done with shift registers to provide a bank of inputs or outputs through SPI. Each slave copies input to output in the next clock cycle until the active low SS line goes high. Such a feature only requires a single SS line from the master, rather than a separate SS line for each slave.

Some slave devices are designed to ignore any SPI communications in which the number of clock pulses is greater than specified. Others do not care, ignoring extra inputs and continuing to shift the same output bit. It is common for different devices to use SPI communications with different lengths, as, for example, when SPI is used to access the scan chain of a digital IC by issuing a command word of one size (perhaps 32 bits) and then getting a response of a different size (perhaps 153 bits, one for each pin in that scan chain).

Below is an example of bit-banging the SPI protocol as an SPI master with CPOL=0, CPHA=0, and eight bits per transfer. The example is written in the C programming language. Because this is CPOL=0 the clock must be pulled low before the chip select is activated. The chip select line must be activated, which normally means being toggled low, for the peripheral before the start of the transfer, and then deactivated afterwards. Most peripherals allow or require several transfers while the select line is low; this routine might be called several times before deselecting the chip.

For any microcontroller project, interfacing a display unit with it would make the project a lot easier and appealing for the user to interact with. The most commonly used display unit for microcontrollers is the 16×2 Alpha numeric displays. These types of displays are not only useful to display vital information to the user but can also act as a debugging tool during the initial developmental stage of the project. So, in this tutorial we will learn how we can interface a 16×2 LCD display with the STM32F103C8T6 STM32 Development board and program it using the Arduino IDE. For people who are familiar with Arduino this tutorial will just be a cake walk since they both are very similar. Also to learn more about STM32 Blue Pill Board follow our getting started tutorial.

As told earlier the Energia IDE provides a beautiful library which makes the interfacing a piece of cake and hence it’s not mandatory to know anything about the display module. But, would didn’t it be interesting to show what we are using!!

The name 16×2 implies that the display has 16 Columns and 2 Rows, which together (16*2) forms 32 boxes. One single box would look something like this in the picture below

A single box has 40 pixels (dots) with a matrix order of 5 Rows and 8 columns, these 40 pixels together forms one character. Similarly, 32 characters can be displayed using all the boxes. Now lets take a look at the pinouts.

Out of all these 16 pins, only 10 pins are to be used mandatory for the proper working of the LCD if you want to know more about these LCD display jump to this 16x2 LCD article.

As you can see the complete connection is made over a breadboard. We need a FTDI board to program the STM32 Microcontroller. So similar to our previous tutorial, we have wired the FTDI board to STM32, the Vcc and ground pin of the FDTI programmer is connected to the 5V pin and ground pin of the STM32 respectively. This is used to power the STM32 board and the LCD since both can accept can +5V. The Rx and Tx pin of the FTDI board is connected to the A9 and A10 pin of the STM32 so that we can program the board directly without the boot loader.

Next the LCD has to be connected to the STM32 board. We are going to use the LCD in 4-bit mode, so we have to connect the 4 data bit pins (DB4 to DB7) and the two control pin (RS and EN) to the STM32 board as shown in the STM32F103C8T6 LCD interfacing circuit diagram above. Further the table below will help you in making the connection.

As told in this tutorial we will be using the Arduino IDE to program our STM32 Microcontroller. But, the Arduino IDE by default will not have the STM32 board installed, hence we have to download a package and prepare the Arduino IDE for the same. This is exactly what we did in our previous tutorial getting started with STM32F103C8T6 using Arduino IDE. So if you have not installed the required packages fall back to this tutorial and follow it before you continue here.

Once the STM32 Board is installed in the Arduino IDE, we can start programming. The program is very similar to that of an Arduino board, the only thing that will change are the pin names since the notations are different for STM32 and Arduino. The complete program is given at the end of this page, but to explain the program I have split it into small meaningful snippets as shown below.

One noticeable advantage of using Arduino for programming our microcontrollers is that Arduino has readymade libraries for almost every famous sensors and actuators. So here we start our program by including the LCD library which makes the programming a lot easier.

In the next line we have to specify to which GPIO pins of the STM32 we have connected the LCD display control and data lines. To do this we have to check our hardware, for ease you can also refer to the table given at the top which lists the pin names of LCD against the GPIO pin of STM32. After mentioning the pins we can initialise the LCD using the LiquidCrystal function. We also name our LCD as “lcd” as shown below.

Next we step inside the setup function. Here first we have mention what type of LCD we are using. Since it is a 16*2 LCD we use the line lcd.begin(16,2). The code inside the void setup function gets executed only once. So we use it to display an intro text which comes on the screen for 2 seconds and then gets cleared. To mention the position where the text has to appear we use the function lcd.setcursor and to print the text we use the lcd.print function. For instance lcd.setCursor(0,0) will set the cursor at first row and first column where we print “Interfacing LCD” and the function lcd.setCursor (0,1) moves the cursor to second row first column where we print the line “CircuitDigest”.

After displaying the intro text we hold the program for 2 seconds by creating a delay so that the user the can read the intro message. This delay is created by the line delay(2000) where 2000 is the delay value in mill seconds. After the delay we clear the LCD using the lcd.clear() function which clears the LCD by removing all the text on LCD.

Finally inside the void loop, we display “STM32 –Blue Pill” on the first line and the value of seconds on the second line. The value of second can be obtained from the millis() function. The millis() is a timer which gets incrementing right from the time the MCU is powered. The value is in form of milli seconds so we divide it by 1000 before displaying it on our LCD.

Make the connections as show in the circuit diagram and use the code given below on Arduino IDE. Go to tools and make sure the right board is selected as done in getting started tutorial. Also, before uploading the program make sure the boot 0 jumper is set to 1as shown in the image below and press the reset button. When the upload button is pressed is code should get uploaded and the message will be shown on LCD as show in the image below.

As discussed in the above paragraph you should be able to notice the output as soon as the code is uploaded. But this program will not work the next time when you power up the board, since the board is still in programming mode. So once the program is uploaded the jumper on boot 0 should be changed back to 0 positions as show below. Also now since the program is uploaded to the STM32 board already we do not need the FTDI board and the whole set-up can be powered by the micro-USB port of the STM32 board as well as shown below.

This is just a simple interfacing project to help use the LCD display with STM32 board, but further you can use this to build cool projects. Hope you understood the tutorial and learnt something useful from it. If you had faced any problem in getting it to work, please use the comment section to post the problem or use the forums for other technical questions. The complete working of LCD display with STM32 can also be found as a video given below.

Since it’s inception the Arduino IDE has demonstrated the desire to support all kind of platforms, from Arduino clones and variations of different manufacturers to third party boards like the ESP32 and ESp8266. As more people get familiar with the IDE, they are beginning to support more boards that are not based on ATMEL chips and for today’s tutorial we will look on one of such boards. We will examine how to program the STM32 based, STM32F103C8T6 development board with the Arduino IDE.

The STM32 board to be used for this tutorial is none other than the STM32F103C8T6 chip based STM32F1 development board commonly referred to as “Blue Pill” in line with the blue color of its PCB. Blue Pill is powered by the powerful 32-bit STM32F103C8T6 ARM processor, clocked at 72MHz. The board operates on 3.3v logic levels but its GPIO pins have been tested to be 5v tolerant. While it does not come with WiFi or Bluetooth like the ESP32 and Arduino variants, it offers 20KB of RAM and 64KB of flash memory which makes it adequate for large projects. It also possesses 37 GPIO pins, 10 of which can be used for Analog sensors since they have ADC enabled, along with others which are enabled for SPI, I2C, CAN, UART, and DMA. For a board which costs around $3, you will agree with me that these are impressive specs. A summarized version of these specifications compared with that of an Arduino Uno is shown in the image below.

Based on the specs above, the frequency at which Blue pill operates is about 4.5 times higher than an Arduino UNO, for today’s tutorial, as an example on how to use the STM32F1 board, we will connect it to a 1.44″ TFT display and program it to calculate the “Pi” constant. We will note how long it took the board to obtain the value an compare it with the time it takes an Arduino Uno to perform the same task.

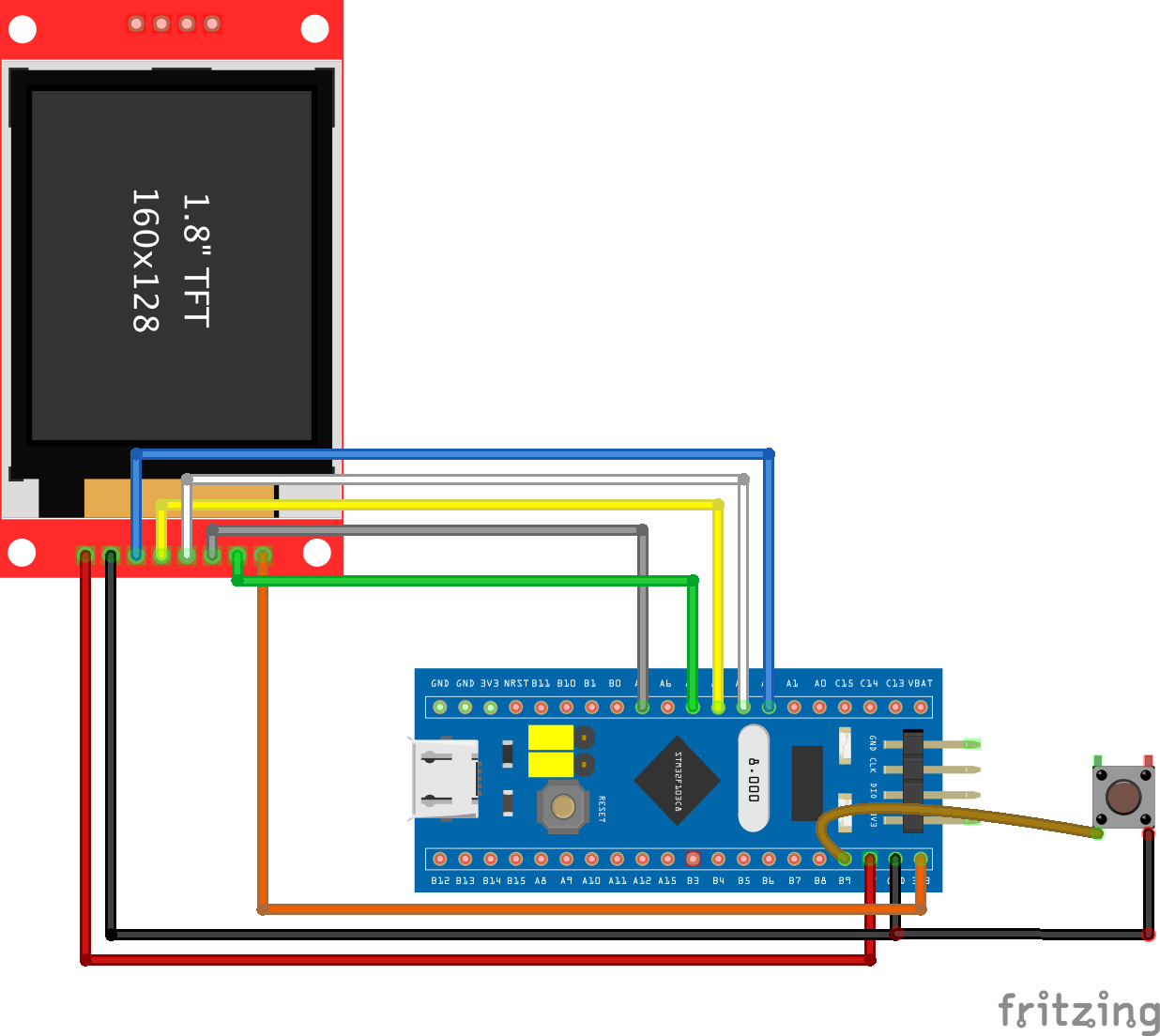

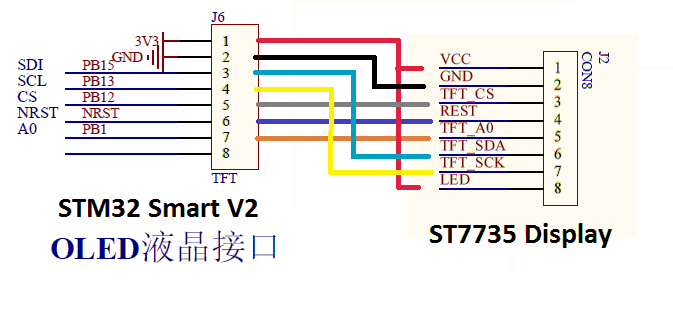

As mentioned earlier, we will connect the STM32F1 board to the1.8″ ST7735 based colored TFT Display along with a push button. The push button will be used to instruct the board to start the calculation.

Go over the connections once again to be sure everything is as it should be as it tends to get a little bit tricky. With this done, we proceed to set up the STM32 board to be programmed with the Arduino IDE.

As with most boards not made by Arduino, a bit of setup needs to be done before the board can be used with the Arduino IDE. This involves installing the board file either via the Arduino Board manager or downloading from the internet and copy the files into the hardware folder. The Board Manager route is the less tedious one and since the STM32F1 is among the listed boards, we will go that route.

Start by adding the link for the STM32 board to the Arduino preference lists. Go to File -> Preferences, then enter this URL ( http://dan.drown.org/stm32duino/package_STM32duino_index.json ) in the box as indicated below and click ok.

The code will be written the same way we’d write any other sketch for an Arduino project, with the only difference being the way the pins are referenced.

To be able to easily develop the code for this project, we will use two libraries which are both modifications of standard Arduino Libraries to make them compatible for the STM32. We will use the modified version of the Adafruit GFX and the Adafruit ST7735 libraries. Both libraries can be downloaded via the links attached to them.

With this done, we create an object of the ST7735 library which will be used to reference the display all through the entire project. We also indicate the pin of the STM32 to which the pushbutton is connected and create a variable to hold its state.

Next, we initialize serial communication and the screen, setting the background of the display to black and calling the printUI() function to display the interface.

We start by reading the state of the push button. If the button has been pressed, we remove the current message on the screen using the removePressKeyText() and draw the changing progress bar using the drawBar() function. We then call the start calculation function to obtain and display the value of Pi along with the time it took to calculate it.

The remaining part of the code are the functions called to achieve the tasks from drawing the bar to calculating the Pi. Most of these functions have been covered in several other tutorials that involve the use of the ST7735 display.

Uploading sketches to the STM32f1 is a little bit complex compared to standard Arduino compatible boards. To upload code to the board, we need an FTDI based, USB to Serial converter.

With this done, we then change the position of the board’s state jumper to position one (as shown in the gif below), so as to put the board in programming mode. Press the reset button on the board once after this and we are ready to upload the code.

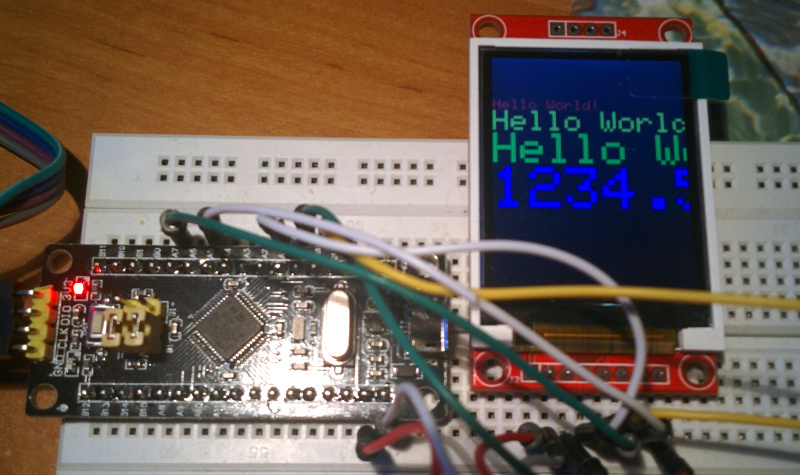

With the code complete, follow the upload process described above to upload the code to your setup. You should see the display come up as shown in the Image below.

Press the pushbutton to start the calculation. You should see the progress bar slide gradually until the end. At the end of the process, the value of Pi is displayed along with the time which the calculation took.

Comparing these two values, we see that “Blue Pill” is over 7 times faster than the Arduino Uno. This makes it ideal for projects which involves heavy processing and time constraints. The small size of the Blue pill also serves as an advantage here as it is only a bit bigger than the Arduino nano and it can be used in place where the Nano won’t be fast enough.

That’s it for today’s tutorial guys. What will you be building with the Blue Pill? feel free to share along with any questions you might have, under the comment section.

Hi guys, welcome to today’s tutorial. Today, we will look on how to use the 1.8″ ST7735 colored TFT display with Arduino. The past few tutorials have been focused on how to use the Nokia 5110 LCD display extensively but there will be a time when we will need to use a colored display or something bigger with additional features, that’s where the 1.8″ ST7735 TFT display comes in.

The ST7735 TFT display is a 1.8″ display with a resolution of 128×160 pixels and can display a wide range of colors ( full 18-bit color, 262,144 shades!). The display uses the SPI protocol for communication and has its own pixel-addressable frame buffer which means it can be used with all kinds of microcontroller and you only need 4 i/o pins. To complement the display, it also comes with an SD card slot on which colored bitmaps can be loaded and easily displayed on the screen.

The schematics for this project is fairly easy as the only thing we will be connecting to the Arduino is the display. Connect the display to the Arduino as shown in the schematics below.

Due to variation in display pin out from different manufacturers and for clarity, the pin connection between the Arduino and the TFT display is mapped out below:

We will use two libraries from Adafruit to help us easily communicate with the LCD. The libraries include the Adafruit GFX library which can be downloaded here and the Adafruit ST7735 Library which can be downloaded here.

We will use two example sketches to demonstrate the use of the ST7735 TFT display. The first example is the lightweight TFT Display text example sketch from the Adafruit TFT examples. It can be accessed by going to examples -> TFT -> Arduino -> TFTDisplaytext. This example displays the analog value of pin A0 on the display. It is one of the easiest examples that can be used to demonstrate the ability of this display.

The second example is the graphics test example from the more capable and heavier Adafruit ST7735 Arduino library. I will explain this particular example as it features the use of the display for diverse purposes including the display of text and “animated” graphics. With the Adafruit ST7735 library installed, this example can be accessed by going to examples -> Adafruit ST7735 library -> graphics test.

The first thing, as usual, is to include the libraries to be used after which we declare the pins on the Arduino to which our LCD pins are connected to. We also make a slight change to the code setting reset pin as pin 8 and DC pin as pin 9 to match our schematics.

Next, we create an object of the library with the pins to which the LCD is connected on the Arduino as parameters. There are two options for this, feel free to choose the most preferred.

Next, we move to the void setup function where we initialize the screen and call different test functions to display certain texts or images. These functions can be edited to display what you want based on your project needs.

All the functions called under the void setup function, perform different functions, some draw lines, some, boxes and text with different font, color and size and they can all be edited to do what your project needs.

Uploading the code to the Arduino board brings a flash of different shapes and text with different colors on the display. I captured one and its shown in the image below.

That’s it for this tutorial guys, what interesting thing are you going to build with this display? Let’s get the conversation started. Feel free to reach me via the comment section if you have any questions as regards this project.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey