ultra low power lcd display free sample

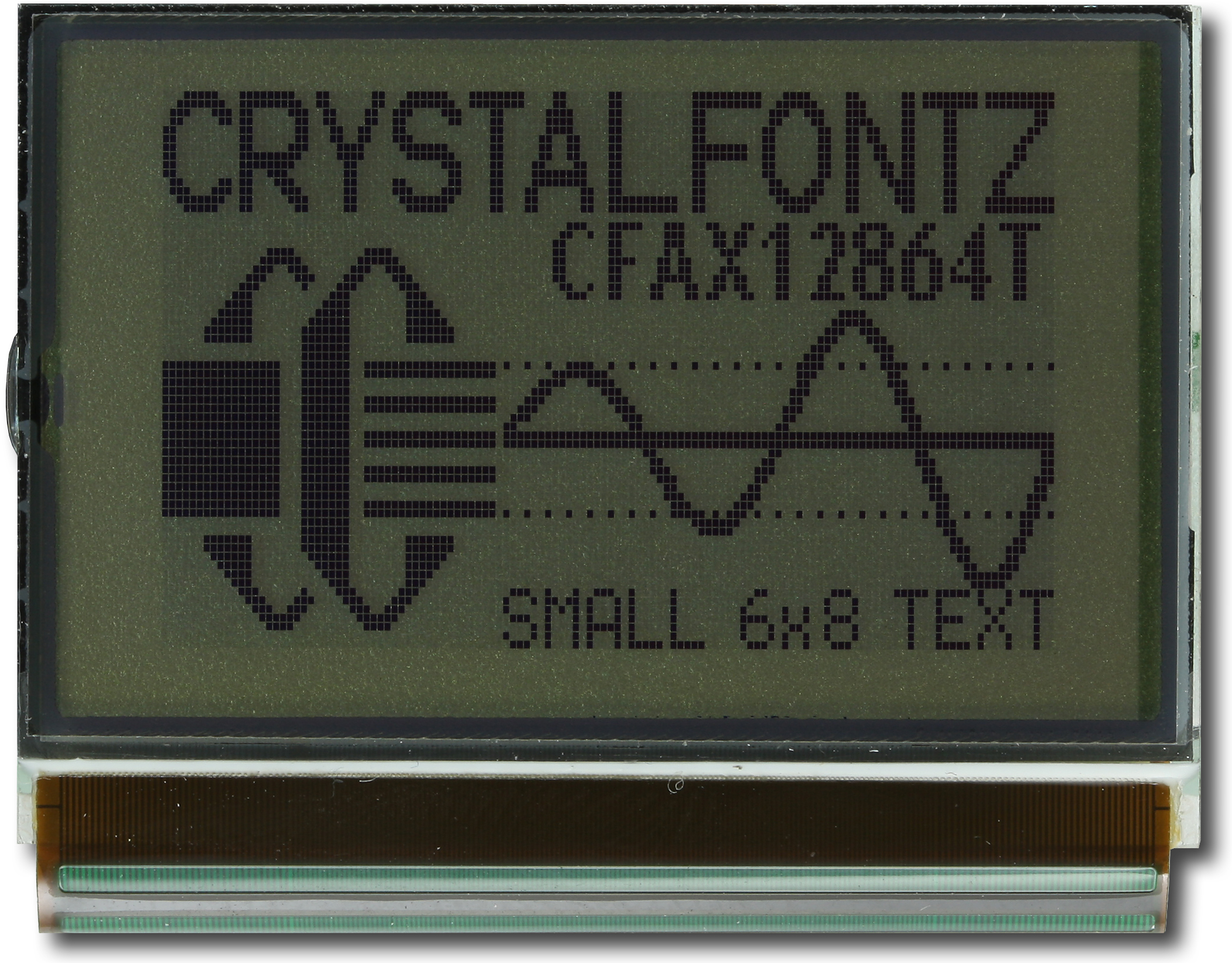

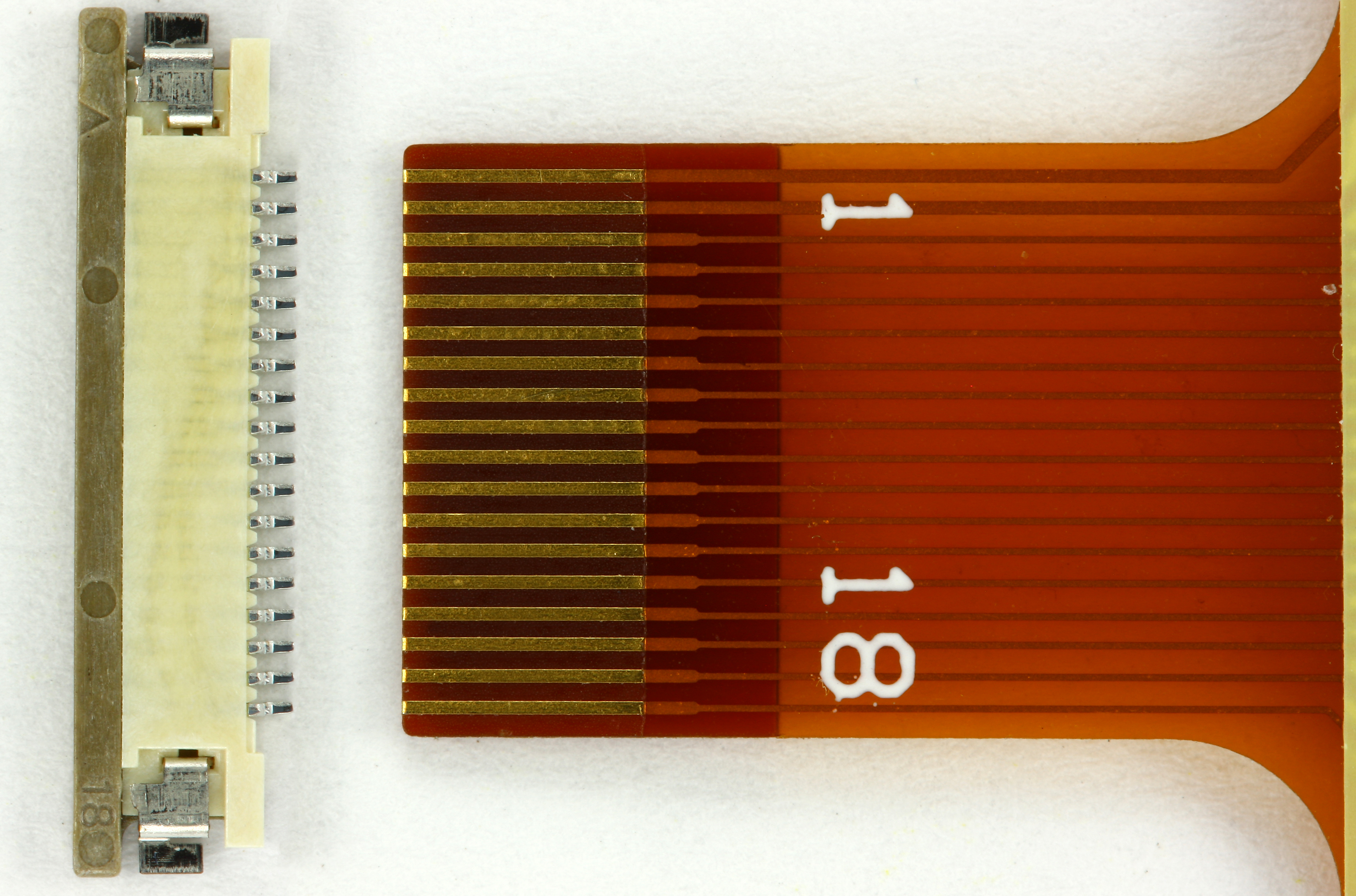

This is a thin, extremely low-power 128x64 graphic LCD display module. It has no backlight, so consumes no power illuminating the display. However, if you wanted to backlight the module, the rear polarizer is transflective, so you could add your own lighting solution there. This display is perfectly suited for hand-held or any application requiring low power consumption or a very thin display. A row of icons is shown automatically top of the display without having to be rendered. This display has an integrated controller and the tail is designed to mate with standard 18-conductor 0.5mm pitch ZIF connectors (typical would be Omron XF2L18351A/ DigiKey P/N OR754CT-ND).

At 2.2" diagonal, this transflective display is big enough to get all the information across. Plus, it"s readable in most lighting environments, from indoor light to direct sunlight. If you"re looking for a display that can be read in low-light situations, check out the backlight version of this display. This display has a 128x64 monochrome array, plus a row of addressed icons along the top edge of the display.

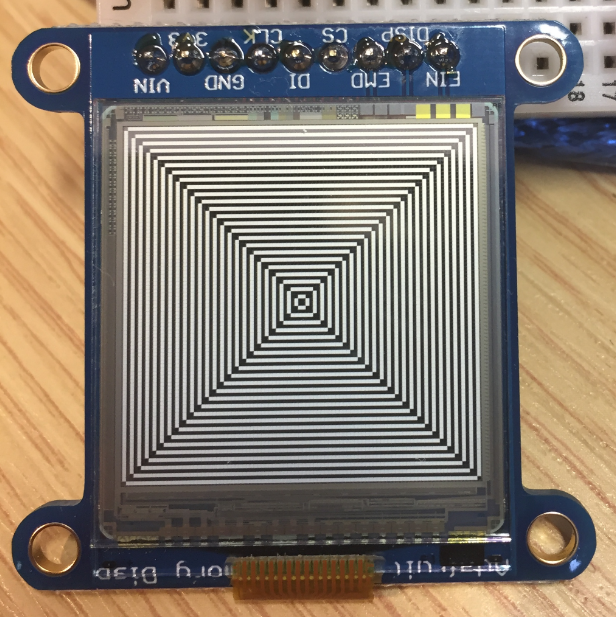

The included adapter board simplifies integrating the display into a product or bringing up a demonstration of the display. The board breaks the ZIF tail out into a 16-position 0.1" header. This makes wiring the display simple and solder-free. The 2x2-56 threaded standoffs on the adapter board enable the entire assembly to be mounted into a final design.

Ultra-low-power displays consume very little energy, and the two primary technologies used for these types of displays are bistable and low refresh rate displays. They are used when there is a need for a battery-powered device, want maximum life between charges, and the content being displayed does not change very frequently.

The common uses for ultra-low-power displays are e-readers and electronic price tags. Some of the other applications we have seen are secondary displays for handheld devices and battery-powered products like locks, remote-mounted homes, and industrial products.

Probably the most well know bi-stable low-power display is e-paper technology historically used on e-readers. This technology is available in both monochrome and color.

In a monochrome e-paper display, millions of tiny liquid-filled capsules contain black and white charged ink particles. These capsules are sandwiched between a grid of electrodes. Applying a charge to the electrodes causes the ink particles to migrate to the top of the capsule, and depending on the polarity of the charge, it changes the color of the surface of the display.

E-paper is a reflective technology and, with good ambient light, has an excellent contrast ratio. One of the characteristics of e-paper is that the background is white, whereas many reflective display technologies like LCD have a gray or greenish background. One disadvantage is that E-paper requires front lighting if used in low-light conditions.

Displaying static images on an e-paper display uses very little energy (uW). However, it can require more power (mW) to update the screen than other technologies like LCD in the same size and resolution.

The backlight uses most of the power in a standard TFT display. For example, on a 7” TFT panel, the backlight uses almost 80% of the energy consumed for an average brightness display. The digital circuitry utilizes the remaining power to sustain the picture.

The first step of building a low-power TFT is to move to a reflective or transflective display and eliminate the power consumption of the backlight when the display can use ambient light.

Choosing a Transflective display is a good trade-off since it comes with a backlight that, when turned, the display becomes reflective. However, there is some trade-off in that the reflectance of a transflective display is lower than a pure reflective display. We use an advanced LCD driver chip to reduce the power further to drive the display at different refresh rates.

We use an advanced LCD driver chip to reduce the power further, which allows the display to be driven at different refresh rates. The drivers have two modes; a standard TFT mode that enables the display to operate like a standard TFT being able to do video rate, 60Hz, updates, and a low-power mode where the display refreshes at a rate of 1Hz. This mode is excellent for holding static images and using very little energy. Figure 2.0 depicts the driving methodology. Using these drivers, you can reduce the power of the digital portion of the display by 60%.

Table 2.0 shows a comparison study that we did for a thermostat application to compare different low-power technologies. In this study, the display is active for 15 minutes, and then it shows static images for the remainder of the day.

Conclusion: Depending on your application, either low-power TFT or e-paper may be suitable. If power is critical for your application and requires maintaining an image on display for long periods, consider these great technologies.

US Micro Products has designed displays with both technologies for special low-power applications and can do the same for your product. So let us help you with your display requirements; we have expertise that spans multiple markets and technologies.

If you have a project that is considering taking advantage of any display technology, US Micro Products can provide a solution designed for your application. Send us an email at sales@usmicroproducts.com.

This is a very low-power LCD clock, based on an AVR128DA48, capable of running for over three years from a CR2032 button cell, or for ever from a solar cell:

Every minute it also briefly displays the temperature, using the AVR128DA48"s on-chip temperature sensor, and the battery voltage, by using the ADC to read its own supply voltage. There"s also an I2C connection so you can add an external sensor, for example to show the humidity in addition to the other readings.

Although liquid crystal displays (LCDs) are relatively old technology, they still offer several advantages over newer types of display, including low power, low cost, and readability.

I recently bought some Densitron LCD displays on eBay for a few pounds/dollars, and I"d been wanting to try building a low-power clock around them, to see just how low I could get the power consumption. The displays are a standard type, available with compatible pinouts from several manufacturers. They are called static (as opposed to multiplexed), which means that every segment comes to a separate pin on the edge connector. This makes 28 pins for the segments plus three decimal points, a colon, and a common pin, adding up to 33 pins altogether. The displays I"ve found usually have two common pins, and also typically have other special-purpose segments, such as a minus sign, in a 40-pin package.

The displays are usually clear, but when you apply a voltage of about 3.3V between a segment and the common line the segment turns black. The displays I"m using have a reflective backing; they are also available with a translucent backing so you can add a backlight behind them.

There"s one catch; you can"t use a DC voltage to turn on the segments, because this would cause electrolysis to occur which would slowly degrade the display. The solution is to use AC by switching the polarity across the segment at a low frequency; 32Hz is usually recommended. Fortunately this is easy to do in software

Most 40-pin, 33mm row spacing displays should be compatible with this board; here are some I"ve found. These all have 4 digits and 3 decimal points on pins 5 to 27, 29 to 32, and 34 to 37, and commons on 1 and 40, plus a few extra symbols as shown:

The circuit is less complicated than it looks. Each segment simply connects to one I/O line on the processor. All the segments for one digit go to the same port, with the decimal point going to bit 7, segment A going to bit 6, through to segment G going to bit 0 (with a couple of exceptions explained below).

Because of the number of interconnections I didn"t fancy prototyping this project by hand, but went straight to designing a PCB in Eagle, and I sent it to PCBWay for manufacture. I tried to make the PCB as general purpose as possible. It caters for any of the displays in the above table; to select which of the extra symbols you want to display you need to fit an 0Ω resistor to the board to act as a link.

The processor is an AVR128DA48 in a TQFP-48 package, but the PCB would work with a range of other 48-pin processors. The AVR128DB48 would be suitable, as would the lower memory versions of these two devices, down to the AVR32DA48 and AVR32DB48. However, you only save a few pence/cents by choosing the lower memory versions, so I don"t really see the point.

The ATmega4809 and its lower-memory siblings, down to the ATmega809, are pin compatible with the DA and DB chips in the same packages, and so could also be used on this board; the only restriction is that the pins I"ve used for I2C, PF2 and PF3, only support slave I2C on the ATmega4809.

Alternatively, if you want to power the clock from a 3V solar cell there are holes to allow you to fit a supercapacitor in place of the coin cell; I used a PowerStor 0.47F 5V one

The PCB also includes a 4-pin JST PH socket, providing an I2C interface compatible with Adafruit"s STEMMA system or the Grove system. You can use this to connect a sensor to the board, for example to show the humidity as well as the time and temperature, or you could use it to make the board an I2C slave so it can be used as an I2C display for other projects.

There"s no multiplexing, so to display a segment pattern we just need to write the appropriate value from the segment array, Char[0] to Char[11], to the port corresponding to the digit. Ports D, C, and A provide eight I/O lines each, so these map in a logical way to the seven segments and decimal point in digits 0 to 2. There"s a slight complexity with digit 3 because Port B only has six I/O lines available, so the segment corresponding to bit 6 is provided by PF5. The colon or other symbol is controlled by PF4.

The interrupt service routine first toggles all the I/O lines connected to the LCD segments, and the common connections. Every 32 calls, or every half second, it calculates the current time, and checks whether the buttons are pressed. If the MINS or HRS buttons are pressed it advances the time by a minute or an hour respectively. It then calls the routine DisplayTime() to update the time, or at the end of each minute it calls DisplayVoltage() to display the battery voltage for three seconds, followed by DisplayTemp() to display the temperature for three seconds:

DisplayTime() copies the digits representing the current time to the corresponding output ports, specified by Digit[0] to Digit[3]. It also flashes the colon:

Unlike earlier AVR microcontrollers, where you had to calibrate the temperature sensor, the AVR DA and DB series have been calibrated during manufacture and contain calibration parameters in ROM. The temperature display is therefore pretty accurate without any additional calibration.

The processor spends most of its time in power-down sleep mode, to save power, and is woken up by the 64Hz interrupt from the Real-Time Clock peripheral. I measured the average power consumption at 3.3V for four different clock frequencies:

Usually you"d expect the power consumption to increase with processor clock frequency, so at first sight these figures are puzzling. The explanation is that at higher clock frequencies the time taken to execute the interrupt service routine is shorter, allowing the processor to spend a higher proportion of the time asleep.

The 32.768kHz external crystal oscillator has a low-power mode, and selecting this reduced the average power consumption with a 24MHz clock from 9.5µA to 7.3µA. The AVR128DA48 datasheet doesn"t seem to mention any downside to choosing the low-power mode, so I used this setting.

With a 0.47F supercapacitor you can expect a current of 0.47A for 1 second. This gives an expected life of 0.47/7.3x10‑6/60/60 or about 18 hours, which I confirmed by testing it. This should be sufficient to keep the clock running overnight with a suitable solar cell providing power during daylight.

The HRS button doesn"t affect the seconds and minutes timing; this is designed to allow you to switch between Standard Time and Daylight Saving Time without affecting the clock setting.

Compile the programs using Spence Konde"s Dx Core on GitHub. Choose the AVR DA-series (no bootloader) option under the DxCore heading on the Board menu. Check that the subsequent options are set as follows (ignore any other options):

An import function allows additionally to use Windows fonts. With the FontEditor it is easy to generate for example Cyrillic, Greek and Arabic fonts. The preview function shows immediately the size and style in simulation window. When the testboard EA 9780-2USB is connected to the USB port, you can see the character (or any predefined text) live on the display which is plugged-in!

When I say ultra-low-power it is not hyperbole, the display itself uses zero power to display, the driver board electronics use about 2.1W total and the media player is ticking along at approximately 1.4W. A comparably sized sunlight readable LCD display has a power requirement of 1450W to 1850W, ie well over 400 times the power requirement.

When the display changes the image the power consumption increases to a total of approximately 18W for 6 seconds, and as image updates are typically infrequent, the average stays incredibly low.

Display: As indicated in the table above the e-paper display, made using three 42″ E Ink panels, does not use any power to show the image, it is literally zero power. The actual display only consumes power when the content is updated and we have included that in the figures for the driver board as shown above.

Controller/Driver: The E Ink driver board is our modelEPM-100, there is one for each panel. They consume about 0.7W each when idle and together with the panel consume about 14.6W when writing full screen content. I mention full screen as it is possible to write to part of the screen. Update 1 Oct 2021: We have new code to further reduce the idle power consumption and will provide revised figures on the reduced power consumption shortly.

Media Player: For this project we used a Raspberry Pi 3B+, which is very compact, low power at approximately 1.4W when idle and 3W when processing, and quite capable for this signboard application. The image is downloaded as a single image, the Pi then splits the image into three parts and writes the image to the display one panel at a time. There are three panels and each takes about 2 seconds to update.

The EPM-100 driver could sit behind a power switch so that it is only activated when needed for writing to the display. We made such a circuit board and it could be triggered by a command from the Pi.

Both the Pi and the driver board could sit behind a remotely activated power switch so both of them are only powered on when needed. This would need a suitable command passed from the modem.

With such a low power display system solar and/or wind power may be an option. Clearly there are design considerations as the positioning and size of the solar panel is important and this may conflict with the display installation. Also, solar is dependent on clear skies so cloudy environments need larger solar panels and larger batteries. Wind power clearly relies on wind and a suitably sized fan or turbine.

Thanks to being a reflective digital display technology these can be completely Dark Sky compliant, they emit zero light as a display technology. For example here is a photo of these displays, clearly very visible in sunlight but also visible purely from ambient light at night.

The photo below shows the installation of the LED strip. This also has an ambient light sensor with a delay so vehicle headlights do not turn the light off when passing.

DISPLAY VISIONS" EA-DOGS102 series graphic LCDs are available in an FSTN positive transflective, STN negative transmissive, and FSTN positive reflective version. These displays have a 2.54 mm pitch and can be soldered directly or plugged into socket strips. Therefore, cumbersome gluing procedures, the need for designing a special mounting device, and error-prone cable connections that may lose contact are no longer a concern.

This LCD family was designed for use in the German industry and will have an availability of 15+ years. The extremely efficient ratio of external dimensions to the active display area helps in designing very compact devices. Furthermore, its low-power use [single supply 2.5 V to 3.3 V (typically 250 µA)] makes it ideal for handheld applications.

The EA 9780-4USB development board and free windows simulator are all users require to evaluate pin connected chip-on-glass LCDs with and without backlight. Simply plug the 2.54 mm connector pins of the display into the socket strips of the development board. Proprietary hardware or software development is not required. Decisions can be made quickly at a minimum expense.

Recently, ‘Liquid crystal display (LCD) vs. organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display: who wins?’ has become a topic of heated debate. In this review, we perform a systematic and comparative study of these two flat panel display technologies. First, we review recent advances in LCDs and OLEDs, including material development, device configuration and system integration. Next we analyze and compare their performances by six key display metrics: response time, contrast ratio, color gamut, lifetime, power efficiency, and panel flexibility. In this section, we focus on two key parameters: motion picture response time (MPRT) and ambient contrast ratio (ACR), which dramatically affect image quality in practical application scenarios. MPRT determines the image blur of a moving picture, and ACR governs the perceived image contrast under ambient lighting conditions. It is intriguing that LCD can achieve comparable or even slightly better MPRT and ACR than OLED, although its response time and contrast ratio are generally perceived to be much inferior to those of OLED. Finally, three future trends are highlighted, including high dynamic range, virtual reality/augmented reality and smart displays with versatile functions.

Display technology has gradually but profoundly shaped the lifestyle of human beings, which is widely recognized as an indispensable part of the modern world

In this review paper, we present recent progress on LCDs and OLEDs regarding materials, device structures to final panel performances. First, in Section II, we briefly describe the device configurations and operation principles of these two technologies. Then, in Section III, we choose six key metrics: response time, contrast ratio, color gamut, lifetime, power efficiency, and panel flexibility, to evaluate LCDs and OLEDs. Their future perspectives are discussed in Section IV, including high dynamic range (HDR), virtual reality/augmented reality (VR/AR) and smart displays with versatile functions.

Liquid crystal (LC) materials do not emit light; therefore, a backlight unit is usually needed (except in reflective displays) to illuminate the display panel. Figure 1 depicts an edge-lit TFT-LCD. The incident LED passes through the light-guide plate and multiple films and is then modulated by the LC layer sandwiched between two crossed polarizers

The 90° TN mode was first published in 1971 by Schadt and HelfrichFigure 2a), introducing a so-called polarization rotation effect. As the voltage exceeds a threshold (Vth), the LC directors start to unwind and the polarization rotation effect gradually diminishes, leading to decreased transmittance. This TN mode has a high transmittance and low operation voltage (~5 Vrms), but its viewing angle is somewhat limited

IPS mode was first proposed in 1973 by SorefFigure 2c). As the voltage increases, the strong in-plane fringing electric fields between the interdigital electrodes reorient the LC directors. Such a unique mechanism makes IPS a favorable candidate for touch panels because no ripple effect occurs upon touching the panel. However, the peak transmittance of IPS is relatively low (~75%) because the LC molecules above the electrodes cannot be effectively reoriented. This low transmittance region is called a dead zone

As summarized in Table 1, these four LCD modes have their own unique features and are used for different applications. For example, TN has the advantages of low cost and high optical efficiency; thus, it is mostly used in wristwatches, signage and laptop computers, for which a wide view is not absolutely necessary. MVA mode is particularly attractive for large TVs because a fast response time, high CR and wide viewing angle are required to display motion pictures. On the other hand, IPS and FFS modes are used in mobile displays, where low power consumption for a long battery life and pressure resistance for touch screens are critical.

Abbreviations: FFS, fringe-field switching; IPS, in-plane switching; LCD, liquid crystal display; MVA, multi-domain vertical alignment; TN, twisted nematic; TV, television.

The basic structure of an OLED display, proposed by Tang and VanSlykeFigure 3a. Electrons and holes are injected from electrodes to organic layers for recombination and light emission; hence, an OLED display is an emissive display, unlike an LCD. Currently, multi-layer structures in OLEDs with different functional materials are commonly used, as shown in Figure 3b. The emitting layer (EML), which is used for light emission, consists of dopant and host materials with high quantum efficiency and high carrier mobility. Hole-transporting layer (HTL) and electron-transporting layer (ETL) between the EML and electrodes bring carriers into the EML for recombination. Hole- and electron-injection layers (HIL and EIL) are inserted between the electrodes and the HTL and ETL interface to facilitate carrier injection from the conductors to the organic layers. When applying voltage to the OLED, electrons and holes supplied from the cathode and anode, respectively, transport to the EML for recombination to give light.

Generally, each layer in an OLED is quite thin, and the total thickness of the whole device is <1 μm (substrates are not included). Thus the OLED is a perfect candidate for flexible displays. For an intrinsic organic material, its carrier mobility (<0.1 cm2 Vs−1) and free carrier concentration (1010 cm−3) are fairly low, limiting the device efficiency. Thus doping technology is commonly used

First, upon electrical excitation, 25% singlets and 75% triplets are formed with higher and lower energy, respectively. In a fluorescent OLED, only singlets decay radiatively through fluorescence with an ~ns exciton lifetime, which sets the theoretical limit of the internal quantum efficiency (IQE) to 25%, as shown in Figure 4a.

To evaluate the performance of display devices, several metrics are commonly used, such as response time, CR, color gamut, panel flexibility, viewing angle, resolution density, peak brightness, lifetime, among others. Here we compare LCD and OLED devices based on these metrics one by one.

A fast response time helps to mitigate motion image blur and boost the optical efficiency, but this statement is only qualitatively correct. When quantifying the visual performance of a moving object, motion picture response time (MPRT) is more representative, and the following equation should be used

The last finding is somehow counter to the intuition that a LCD should have a more severe motion picture image blur, as its response time is approximately 1000 × slower than that of an OLED (ms vs. μs). To validate this prediction, Chen et al.

If we want to further suppress image blur to an unnoticeable level (MPRT<2 ms), decreasing the duty ratio (for LCDs, this is the on-time ratio of the backlight, called scanning backlight or blinking backlight) is mostly adopted

As Figure 6 depicts, there are two types of surface reflections. The first one is from a direct light source, i.e., the sun or a light bulb, denoted as A1. Its reflection is fairly specular, and in practice, we can avoid this reflection (i.e., strong glare from direct sun) by simply adjusting the display position or viewing direction. However, the second reflection, denoted as A2, is quite difficult to avoid. It comes from an extended background light source, such as a clear sky or scattered ceiling light. In our analysis, we mainly focus on the second reflection (A2).

To investigate the ACR, we have to clarify the reflectance first. A large TV is often operated by remote control, so touchscreen functionality is not required. As a result, an anti-reflection coating is commonly adopted. Let us assume that the reflectance is 1.2% for both LCD and OLED TVs. For the peak brightness and CR, different TV makers have their own specifications. Here, without losing generality, let us use the following brands as examples for comparison: LCD peak brightness=1200 nits, LCD CR=5000:1 (Sony 75″ X940E LCD TV); OLED peak brightness=600 nits, and OLED CR=infinity (Sony 77″ A1E OLED TV). The obtained ACR for both LCD and OLED TVs is plotted in Figure 7a. As expected, OLEDs have a much higher ACR in the low illuminance region (dark room) but drop sharply as ambient light gets brighter. At 63 lux, OLEDs have the same ACR as LCDs. Beyond 63 lux, LCDs take over. In many countries, 60 lux is the typical lighting condition in a family living room. This implies that LCDs have a higher ACR when the ambient light is brighter than 60 lux, such as in office lighting (320–500 lux) and a living room with the window shades or curtain open. Please note that, in our simulation, we used the real peak brightness of LCDs (1200 nits) and OLEDs (600 nits). In most cases, the displayed contents could vary from black to white. If we consider a typical 50% average picture level (i.e., 600 nits for LCDs vs. 300 nits for OLEDs), then the crossover point drops to 31 lux (not shown here), and LCDs are even more favorable. This is because the on-state brightness plays an important role to the ACR, as Equation (2) shows.

Calculated ACR as a function of different ambient light conditions for LCD and OLED TVs. Here we assume that the LCD peak brightness is 1200 nits and OLED peak brightness is 600 nits, with a surface reflectance of 1.2% for both the LCD and OLED. (a) LCD CR: 5000:1, OLED CR: infinity; (b) LCD CR: 20 000:1, OLED CR: infinity.

Recently, an LCD panel with an in-cell polarizer was proposed to decouple the depolarization effect of the LC layer and color filtersFigure 7b. Now, the crossover point takes place at 16 lux, which continues to favor LCDs.

For mobile displays, such as smartphones, touch functionality is required. Thus the outer surface is often subject to fingerprints, grease and other contaminants. Therefore, only a simple grade AR coating is used, and the total surface reflectance amounts to ~4.4%. Let us use the FFS LCD as an example for comparison with an OLED. The following parameters are used in our simulations: the LCD peak brightness is 600 nits and CR is 2000:1, while the OLED peak brightness is 500 nits and CR is infinity. Figure 8a depicts the calculated results, where the intersection occurs at 107 lux, which corresponds to a very dark overcast day. If the newly proposed structure with an in-cell polarizer is used, the FFS LCD could attain a 3000:1 CRFigure 8b), corresponding to an office building hallway or restroom lighting. For reference, a typical office light is in the range of 320–500 luxFigure 8 depicts, OLEDs have a superior ACR under dark ambient conditions, but this advantage gradually diminishes as the ambient light increases. This was indeed experimentally confirmed by LG Display

Calculated ACR as a function of different ambient light conditions for LCD and OLED smartphones. Reflectance is assumed to be 4.4% for both LCD and OLED. (a) LCD CR: 2000:1, OLED CR: infinity; (b) LCD CR: 3000:1, OLED CR: infinity. (LCD peak brightness: 600 nits; OLED peak brightness: 500 nits).

For conventional LCDs employing a WLED backlight, the yellow spectrum generated by YAG (yttrium aluminum garnet) phosphor is too broad to become highly saturated RGB primary colors, as shown in Figure 9aTable 2. The first choice is the RG-phosphor-converted WLEDFigure 9b, the red and green emission spectra are well separated; still, the green spectrum (generated by β-sialon:Eu2+ phosphor) is fairly broad and red spectrum (generated by K2SiF6:Mn4+ (potassium silicofluoride, KSF) phosphor) is not deep enough, leading to 70%–80% Rec. 2020, depending on the color filters used.

aHere we only consider Cd-based quantum-dots (QDs). For heavy-metal-free QDs, e.g., InP QD, the FWHM is broader (40–50 nm) and color gamut is 70–80%. Their optical efficiency is slightly lower than that of Cd-based QDs.

Recently, a new LED technology, called the Vivid Color LED, was demonstratedFigure 9d), which leads to an unprecedented color gamut (~98% Rec. 2020) together with specially designed color filters. Such a color gamut is comparable to that of laser-lit displays but without laser speckles. Moreover, the Vivid Color LED is heavy-metal free and shows good thermal stability. If the efficiency and cost can be further improved, it would be a perfect candidate for an LCD backlight.

As mentioned earlier, TFT LCDs are a fairly mature technology. They can be operated for >10 years without noticeable performance degradation. However, OLEDs are more sensitive to moisture and oxygen than LCDs. Thus their lifetime, especially for blue OLEDs, is still an issue. For mobile displays, this is not a critical issue because the expected usage of a smartphone is approximately 2–3 years. However, for large TVs, a lifetime of >30 000 h (>10 years) has become the normal expectation for consumers.

Here we focus on two types of lifetime: storage and operational. To enable a 10-year storage lifetime, according to the analysis−6 g (m2-day)−1 and 1 × 10−5 cm3 (m2-day)−1, respectively. To achieve these values, organic and/or inorganic thin films have been developed to effectively protect the OLED and lengthen its storage lifetime. Meanwhile, it is compatible to flexible substrates and favors a thinner display profile

Power consumption is equally important as other metrics. For LCDs, power consumption consists of two parts: the backlight and driving electronics. The ratio between these two depends on the display size and resolution density. For a 55″ 4K LCD TV, the backlight occupies approximately 90% of the total power consumption. To make full use of the backlight, a dual brightness enhancement film is commonly embedded to recycle mismatched polarized light

The power efficiency of an OLED is generally limited by the extraction efficiency (ηext~20%). To improve the power efficiency, multiple approaches can be used, such as a microlens array, a corrugated structure with a high refractive index substrateFigure 11 shows the power efficiencies of white, green, red and blue phosphorescent as well as blue fluorescent/TTF OLEDs over time. For OLEDs with fluorescent emitters in the 1980s and 1990s, the power efficiency was limited by the IQE, typically <10 lm W−1(Refs. 41, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118). With the incorporation of phosphorescent emitters in the ~2000 s, the power efficiency was significantly improved owing to the materials and device engineering−1 was demonstrated in 2011 (Ref. 127), which showed a >100 × improvement compared with that of the basic two-layer device proposed in 1987 (1.5 lm W−1 in Ref. 41). A white OLED with a power efficiency >100 lm W−1 was also demonstrated, which was comparable to the power efficiency of a LCD backlight. For red and blue OLEDs, their power efficiencies are generally lower than that of the green OLED due to their lower photopic sensitivity function, and there is a tradeoff between color saturation and power efficiency. Note, we separated the performances of blue phosphorescent and fluorescent/TTF OLEDs. For the blue phosphorescent OLEDs, although the power efficiency can be as high as ~80 lm W−1, the operation lifetime is short and color is sky-blue. For display applications, the blue TTF OLED is the favored choice, with an acceptable lifetime and color but a much lower power efficiency (16 lm W−1) than its phosphorescent counterpartFigure 11 shows.

Power efficiency of white, red, green and phosphorescent blue and fluorescent/TTF blue OLEDs over time. Data are compiled from Refs. 41, 45, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133.

To compare the power consumption of LCDs and OLEDs with the same resolution density, the displayed contents should be considered as well. In general, OLEDs are more efficient than LCDs for displaying dark images because black pixels consume little power for an emissive display, while LCDs are more efficient than OLEDs at displaying bright images. Currently, a ~65% average picture level is the intersection point between RGB OLEDs and LCDs

Flexible displays have a long history and have been attempted by many companies, but this technology has only recently begun to see commercial implementations for consumer electronics

In addition to the aforementioned six display metrics, other parameters are equally important. For example, high-resolution density has become a standard for all high-end display devices. Currently, LCD is taking the lead in consumer electronic products. Eight-hundred ppi or even >1000 ppi LCDs have already been demonstrated and commercialized, such as in the Sony 5.5″ 4k Smartphone Xperia Z5 Premium. The resolution of RGB OLEDs is limited by the physical dimension of the fine-pitch shadow mask. To compete with LCDs, most OLED displays use the PenTile RGB subpixel matrix scheme

The viewing angle is another important property that defines the viewing experience at large oblique angles, which is quite critical for multi-viewer applications. OLEDs are self-emissive and have an angular distribution that is much broader than that of LCDs. For instance, at a 30° viewing angle, the OLED brightness only decreases by 30%, whereas the LCD brightness decrease exceeds 50%. To widen an LCD’s viewing angle, three options can be used. (1) Remove the brightness-enhancement film in the backlight system. The tradeoff is decreased on-axis brightness

In addition to brightness, color, grayscale and the CR also vary with the viewing angle, known as color shift and gamma shift. In these aspects, LCDs and OLEDs have different mechanisms. For LCDs, they are induced by the anisotropic property of the LC material, which could be compensated for with uniaxial or biaxial films

Cost is another key factor for consumers. LCDs have been the topic of extensive investigation and investment, whereas OLED technology is emerging and its fabrication yield and capability are still far behind LCDs. As a result, the price of OLEDs is about twice as high as that of LCDs, especially for large displays. As more investment is made in OLEDs and more advanced fabrication technology is developed, such as ink-jet printing

Currently, both LCDs and OLEDs are commercialized and compete with each other in almost every display segment. They are basically two different technologies (non-emissive vs. emissive), but as a display, they share quite similar perspectives in the near future. Here we will focus on three aspects: HDR, VR/AR and smart displays with versatile functions.

Both LCD and OLED are HDR-compatible. Currently, the best HDR LCDs can produce brighter highlights than OLEDs, but OLEDs have better overall CRs thanks to their superior black level. To enhance an LCD’s CR, a local dimming backlight is commonly used, but its dimming accuracy is limited by the number of LED segmentations

Also worth mentioning here is ultra-high brightness. Mostly, people pay more attention to the required high CR (CR>100 000:1) of HDR but fail to notice that CR is jointly determined by the dark state and peak brightness. For example, a 12-bit Perceptual Quantizer curve is generated for a range up to 10 000 nits, which is far beyond what current displays can provide

The peak brightness of LCDs could be boosted to 2000 nits or even higher by simply using a high-power backlight. OLEDs are self-emissive, so their peak brightness would trade with lifetime. As a result, more advanced OLED materials and novel structural designs are highly desirable in the future. Another reason to boost peak brightness is to increase sunlight readability. Especially for some outdoor applications, such as public displays, peak brightness is critical to ensure good readability under strong ambient light. As discussed in the section of ‘CR and ACR’, high brightness leads to a high ACR, except that the power consumption will increase.

Immersive VR/AR are two emerging wearable display technologies with great potential in entertainment, education, training, design, advertisement and medical diagnostics. However, new opportunities arise along with new challenges. VR head-mounted displays require a resolution density as high as >2000 ppi to eliminate the so-called screen door effect and generate more realistic immersive experiences.

An LCD’s resolution density is determined by the TFTs and color filter arrays. In SID 2017, Samsung demonstrated an LCD panel with a resolution of 2250 ppi for VR applications. The pitches of the sub-pixel and pixel are 3.76 and 11.28 μm, respectively. Meanwhile, field sequential color provides another promising option to triple the LCD resolution density

As for AR applications, lightweight, low power and high brightness are mainly determined by the display components. LC on silicon can generate high brightness

Currently, displays are no longer limited to traditional usages, such as TVs, pads or smartphones. Instead, they have become more diversified and are used in smart windows, smart mirrors, smart fridges, smart vending machines and so on. They have entered all aspects of our daily lives.

As these new applications are emerging, LCDs and OLEDs have new opportunities as well as new challenges. Let us take a vehicle display as an example: high brightness, good sunlight readability, and a wide working temperature range are required

We have briefly reviewed the recent progress of LCD and OLED technologies. Each technology has its own pros and cons. For example, LCDs are leading in lifetime, cost, resolution density and peak brightness; are comparable to OLEDs in ACR, viewing angle, power consumption and color gamut (with QD-based backlights); and are inferior to OLED in black state, panel flexibility and response time. Two concepts are elucidated in detail: the motion picture response time and ACR. It has been demonstrated that LCDs can achieve comparable image motion blur to OLEDs, although their response time is 1000 × slower than that of OLEDs (ms vs. μs). In terms of the ACR, our study shows that LCDs have a comparable or even better ACR than OLEDs if the ambient illuminance is >50 lux, even if its static CR is only 5000:1. The main reason is the higher brightness of LCDs. New trends for LCDs and OLEDs are also highlighted, including ultra-high peak brightness for HDR, ultra-high-resolution density for VR, ultra-low power consumption for AR and ultra-versatile functionality for vehicle display, transparent display and mirror display applications. The competition between LCDs and OLEDs is still ongoing. We believe these two TFT-based display technologies will coexist for a long time.

Chen J, Hardev V, Hartlove J, Hofler J, Lee E. A high-efficiency wide-color-gamut solid-state backlight system for LCDs using quantum dot enhancement film. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Mori H, Itoh Y, Nishiura Y, Nakamura T, Shinagawa Y. Performance of a novel optical compensation film based on negative birefringence of discotic compound for wide-viewing-angle twisted-nematic liquid-crystal displays. Jpn J Appl Phys

Takeda A, Kataoka S, Sasaki T, Chida H, Tsuda H et al. A super-high image quality multi-domain vertical alignment LCD by new rubbing-less technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Kim KH, Lee K, Park SB, Song JK, Kim SN et al. Domain Divided Vertical Alignment Mode with Optimized Fringe Field Effect. Proceedings of the 18th IDRC, Asia Display

Lee SH, Kim SM, Wu ST. Emerging vertical-alignment liquid-crystal technology associated with surface modification using UV-curable monomer. J Soc Inf Display

Kim SS, You BH, Cho JH, Kim DG, Berkeley BH et al. An 82-in. ultra-definition 120-Hz LCD TV using new driving scheme and advanced Super PVA technology. J Soc Inf Display

Hsiao K, Tang GF, Yu G, Zhang ZW, Xu XJ et al. Development and analysis of technical challenges in the world"s largest (110-in.) curved LCD. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Yu IH, Song IS, Lee JY, Lee SH. Intensifying the density of a horizontal electric field to improve light efficiency in a fringe-field switching liquid crystal display. J Phys D Appl Phys

Lee JH, Zhu XY, Lin YH, Choi WK, Lin TC et al. High ambient-contrast-ratio display using tandem reflective liquid crystal display and organic light-emitting device. Opt Express

Zhu RD, Chen HW, Kosa T, Coutino P, Tan GJ et al. High-ambient-contrast augmented reality with a tunable transmittance liquid crystal film and a functional reflective polarizer. J Soc Inf Display

ITU. Parameter Values for Ultra-High Definition Television Systems for Production and International Programme Exchange. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU; 2015.

Xie RJ, Hirosaki N, Takeda T. Wide color gamut backlight for liquid crystal displays using three-band phosphor-converted white light-emitting diodes. Appl Phys Express

Wang L, Wang XJ, Kohsei T, Yoshimura KI, Izumi M et al. Highly efficient narrow-band green and red phosphors enabling wider color-gamut LED backlight for more brilliant displays. Opt Express

Hosoumi S, Yamaguchi T, Inoue H, Nomura S, Yamaoka R et al. Ultra-wide color gamut OLED display?using a deep-red phosphorescent device with high efficiency, long life, thermal stability, and absolute BT.2020 red chromaticity. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Lee MT, Wang CL, Chan CS, Fu CC, Shih CY et al. Achieving a foldable and durable OLED display with BT.2020 color space using innovative color filter structure. J Soc Inf Display

Sasaki T, Yamaoka R, Nomura S, Yamamoto R, Takahashi K et al. A 13.3-inch 8K × 4K 664-ppi 120-Hz 12-bit display with super-wide color gamut for the BT.2020 standard. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Hashimoto N, Ogita K, Nowatari H, Takita Y, Kido H et al. Investigation of effect of triplet-triplet annihilation and molecular orientation on external quantum efficiency of ultrahigh-efficiency blue fluorescent device. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Lee C, Kim JJ. Enhanced light out-coupling of OLEDs with low haze by inserting randomly dispersed nanopillar arrays formed by lateral phase separation of polymer blends. Small

Shin H, Lee JH, Moon CK, Huh JS, Sim B et al. Sky-blue phosphorescent OLEDs with 34.1% external quantum efficiency using a low refractive index electron transporting layer. Adv Mater

Yamada Y, Inoue H, Mitsumori S, Watabe T, Ishisone T et al. Achievement of blue phosphorescent organic light-emitting diode with high efficiency, low driving voltage, and long lifetime by exciplex-triplet energy transfer technology. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Greinert N, Schoenefeld C, Suess P, Klasen-Memmer M, Bremer M et al. Opening the door to new LCD applications via polymer walls. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Lee S, Moon J, Yang S, Rhim J, Kim B et al. Development of zero-bezel display utilizing a waveguide image transformation element. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Yamazaki A, Wu CL, Cheng WC, Badano A. Spatial resolution characteristics of organic light-emitting diode displays: a comparative analysis of MTF for handheld and workstation formats. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Käläntär K. A directional backlight with narrow angular luminance distribution for widening the viewing angle for an LCD with a front-surface light-scattering film. J Soc Inf Display

Kim HJ, Shin MH, Lee JY, Kim JH, Kim YJ. Realization of 95% of the Rec. 2020 color gamut in a highly efficient LCD using a patterned quantum dot film. Opt Express

Chen PY, Chen CL, Chen CC, Tsai L, Ting HC et al. 65-inch inkjet printed organic light-emitting display panel with high degree of pixel uniformity. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Reinhard E, Heidrich W, Debevec P, Pattanaik S, Ward G et al. High Dynamic Range Imaging: Acquisition, Display, and Image-Based Lighting2nd edn.San Francisco, CA, USA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2010.

Chen HF, Sung J, Ha T, Park Y, Hong CW. Backlight Local Dimming Algorithm for High Contrast LCD-TV. New Delhi, India: Proceedings of ASID; 2006, pp168–pp171.

Yoo O, Nam S, Choi J, Yoo S, Kim KJ et al. Contrast enhancement based on advanced local dimming system for high dynamic range LCDs. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Daly S, Kunkel T, Sun X, Farrell S, Crum P. Viewer preferences for shadow, diffuse, specular, and emissive luminance limits of high dynamic range displays. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Chen CH, Lin FC, Hsu YT, Huang YP, Shieh HP. A field sequential color LCD based on color fields arrangement for color breakup and flicker reduction. J Display Technol

Lin FC, Huang YP, Wei CM, Shieh HPD. Color-breakup suppression and low-power consumption by using the Stencil-FSC method in field-sequential LCDs. J Soc Inf Display

Castles F, Morris SM, Gardiner DJ, Malik QM, Coles HJ. Ultra-fast-switching flexoelectric liquid-crystal display with high contrast. J Soc Inf Display

Ghosh A, Donoghue EP, Khayrullin I, Ali T, Wacyk I et al. Directly patterened 2645 Ppi full color OLED microdisplay for head mounted wearables. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Kimura K, Onoyama Y, Tanaka T, Toyomura N, Kitagawa H. New pixel driving circuit using self-discharging compensation method for high- resolution OLED micro displays on a silicon backplane. J Soc Inf Display

Reinert-Weiss CJ, Baur H, Al Nusayer SA, Duhme D, Frühauf N. Development of active matrix LCD for use in high-resolution adaptive headlights. J Soc Inf Display

Okuyama K, Nakahara T, Numata Y, Nakamura T, Mizuno M et al. Highly transparent LCD using new scattering-type liquid crystal with field sequential color edge light. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap

Görrn P, Sander M, Meyer J, Kröger M, Becker E et al. Towards see-through displays: fully transparent thin-film transistors driving transparent organic light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey