are lcd monitors better than lcd quotation

If you are looking for a new display, you should consider the differences between CRT and LCD monitors. Choose the type of monitor that best serves your specific needs, the typical applications you use, and your budget.

Require less power - Power consumption varies greatly with different technologies. CRT displays are somewhat power-hungry, at about 100 watts for a typical 19-inch display. The average is about 45 watts for a 19-inch LCD display. LCDs also produce less heat.

Smaller and weigh less - An LCD monitor is significantly thinner and lighter than a CRT monitor, typically weighing less than half as much. In addition, you can mount an LCD on an arm or a wall, which also takes up less desktop space.

More adjustable - LCD displays are much more adjustable than CRT displays. With LCDs, you can adjust the tilt, height, swivel, and orientation from horizontal to vertical mode. As noted previously, you can also mount them on the wall or on an arm.

Less eye strain - Because LCD displays turn each pixel off individually, they do not produce a flicker like CRT displays do. In addition, LCD displays do a better job of displaying text compared with CRT displays.

Better color representation - CRT displays have historically represented colors and different gradations of color more accurately than LCD displays. However, LCD displays are gaining ground in this area, especially with higher-end models that include color-calibration technology.

More responsive - Historically, CRT monitors have had fewer problems with ghosting and blurring because they redrew the screen image faster than LCD monitors. Again, LCD manufacturers are improving on this with displays that have faster response times than they did in the past.

Multiple resolutions - If you need to change your display"s resolution for different applications, you are better off with a CRT monitor because LCD monitors don"t handle multiple resolutions as well.

So now that you know about LCD and CRT monitors, let"s talk about how you can use two monitors at once. They say, "Two heads are better than one." Maybe the same is true of monitors!

Outdoor displays need to withstand wear and tear, as they are often exposed to the elements. Sun, wind, rain, snow – you name it, an outdoor display has to be able to handle it.

Yaham LED displays are an excellent option for businesses who want a high-quality display that is flexible, durable, and energy-efficient. In addition, our LED displays use less power than LCDs, making them an eco-friendly choice for your business.

On the other hand, LCD screens are preferred for displays that are needed up close because of their high resolution—for example, handheld gadgets such as smartphones or TV screens. In addition, LCD screens can produce 4K displays which are perfect for watching vivid displays or videos from a closer perspective.

LED screens are flexible, so they can fit various forms and shapes, even fitting round edges. This is why you can see LED displays on corners of buildings or spaces uneven in the area and dynamic in form.

That is why you will not see an LCD screen used on round edges. LCDs are sleek and lightweight which is perfect for mobile devices making them look more attractive and feel handier.

The LCD screens commonly found in outdoor uses can be problematic because they struggle to withstand the elements. On the other hand, LEDs have been improving steadily with higher quality and lower costs, making them a better option for long-term use.

Energy-efficient backlighting indeed allows LED televisions to have an almost 40% lower power consumption than LCD screens and significantly less than a plasma television.

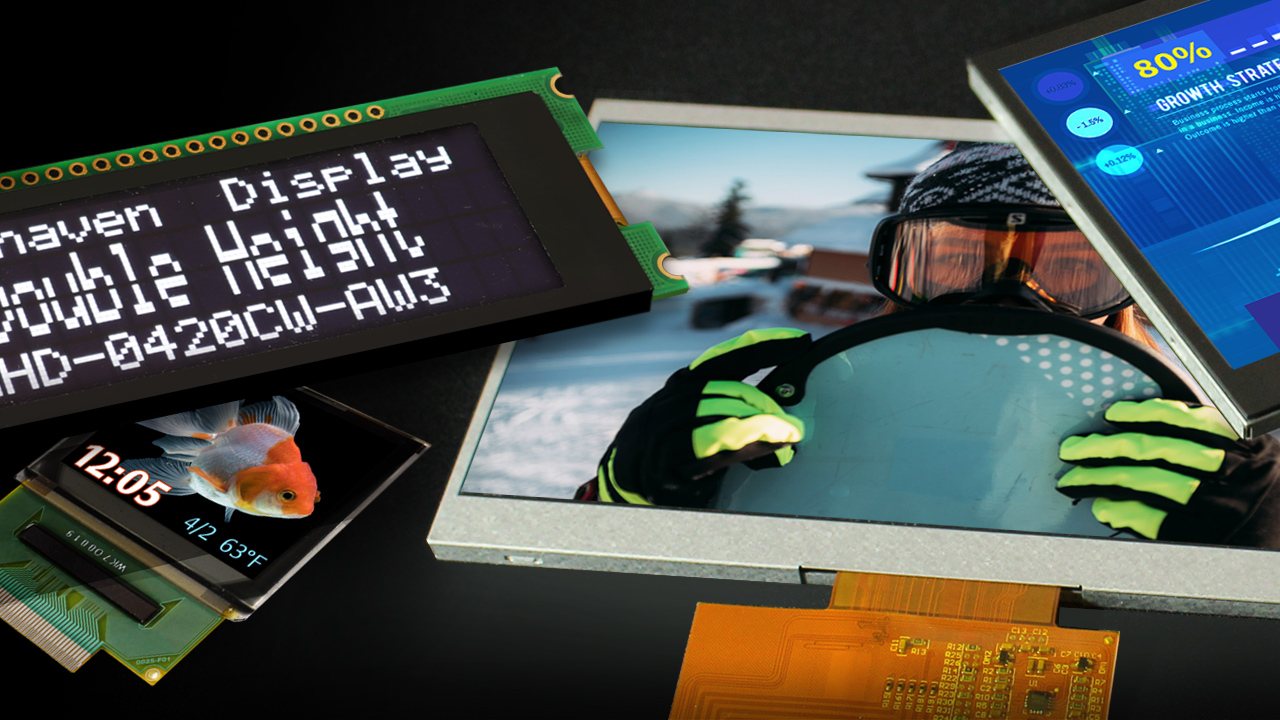

LED stands for Light Emitting Diode. SMD refers to Surface Mounted Diode, a technology that utilizes a process of mounting each LED chip (pixel) directly to a printed circuit board (PCB). Mounting the diodes in this fashion allows displays to be thinner and sleeker than older LED technology. SMD also allows for finer pixel pitch. Simply put, pixel pitch refers to the distance between the diodes and is responsible for resolution. Fine pixel pitch translates into high resolution. Fine pixel pitch is what makes HD and UHD LED possible.

LCD panels are made of a layer of liquid crystal between two pieces of polarized glass. Liquid crystal can not emit light. Backlights are therefore used to illuminate the display. LCD panels are sleek in design, but typically limited to specific sets of dimensions.

LEDs are their own light source. This means that LED video walls are glare free and not subject to many of the problems ambient lighting creates for other video display types.

LCD video walls on the other hand take on a tiled approach. This means that screens are jutted against one another. This approach creates bezels or seams and the final dimensions of the wall is directly dependent on the dimensions of the individual screens.

LED is a versatile display option. Thanks to various IP options, LED video walls can be displayed indoors or outdoors. LED video walls can be built with a variety of internal mechanisms as well. Quick refresh rates and dual power backup can ensure that LED video walls look great on camera. Various pixel pitches can ensure the proper resolution for the right context.

LCD is a more straightforward product and consumers are generally more familiar with LCD. LCD is used for cell phones, computer screens, and most TVs, but is it the best choice for video walls? Ultimately that choice is up to the consumer. LCD is cheaper, but generally less customizable. LCD does not work well for outdoor uses and is generally very limited in terms of size and shape.

Just like anything else, the best video wall product is largely dependant on context. If you like LED technology but are unsure of the process associated in obtaining a LED video wall read: How to Purchase a LED Video Wall Display.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/CRT-vs-LCD-monitor-cfe0b6f375b542928baf22a0478a57a3.jpg)

Before you invest in a new digital display, you need to know what you are shopping for. A lot of technology out there sounds impressive, with names like LED, LCD, cloud-based, IoT, and so on. At Neoti, we believe in educating the customer so they can find the screen solution that fits their needs best. Educated customers have the information they need and are happier and more satisfied with their decisions. When looking for new digital display solutions, you will have to decide between LCD displays and LED display panels, but what does that mean, and what are they? We will explain why LED screens are better than LCD displays.

An LCD screen uses the same basic technology that has been around for many years in cell phones, camcorder viewfinders, and monitors. The screens are made of two layers of glass-like material that are polarized and affixed together. One of the layers has a special polymer coating that holds the individual liquid crystals. An electronic current then passes through the individual crystals and allows the crystal to either pass or block light to create an image. The crystals don’t produce any light, so an external source like a light bulb is needed. The light makes the image visible on the screen.

LED stands for Light Emitting Diode. There are three main LED types; DIP, SMD, and COB. During manufacturing, DIPs (Direct In-line Package) have a red, green and blue LED encapsulated in a bulb and then placed on the Printed Circuit Board (PCB). The SMDs (Surface Mounted Diodes) are mounted directly to a PCB in one slim package. COBs (Chip On Board) are bare LED chips that are mounted directly on the PCB and then covered with a protective coating.

Overall, when talking about picture quality, design flexibility, product lifespan, and maintenance, LED displays are the superior product. As mentioned, LED screens are an improvement over the LCD technology. They provide a seamless display, unlike the LCDs with its tiled bezels. Initially, the LED is more expensive, but it will save money in the long run by using less energy. They are more efficient and will save money on electrical bills. They deliver a crisper, brighter image than LCDs, especially when ambient light is present.

We often get asked, “should I replace my old CRT with a new LCD? What is the difference?” There are several factors to consider including price, resolution, energy savings and disposal. Listed below are some of the top reasons why the LCD may be a better choice.Size and Weight: The color LCD is thinner and much lighter. It is much easier to install into tight areas. The CRT can weigh up to 50 pounds and needs additional bracing and heavier supports.

Power: Energy savings on the LCD can make a big difference in companies having multiple units in production. Savings can be as much as 1/3 over the older CRT.

Summary: Based on price alone, you may choose to stay with the CRT. However, you must consider the energy cost savings to operate an LCD vs. CRT, plus the added cost of disposal for CRTs. In many instances, the CRT may actually cost more in the long run. With its large, high resolution screen and compact housing for easy installation, the LCD offers many advantages over the older CRT technology.

Cathode-ray-tube (CRT) displays have been used extensively in vision research because of their superior response times and reduced motion smear, relative to the liquid crystal displays (LCDs) commonly used in homes and offices. To produce an image on a CRT screen, a stream of electrons is shot at a phosphor-coated screen from an electron gun that can be rapidly turned on or off and repositioned. When hit by the electron stream, the phosphor luminesces for a period that varies with the phosphor’s characteristics. Some phosphors (e.g., P15) have virtually no persistence; others (e.g., P31) have persistence that can remain visible for several seconds (Di Lollo, Seiffert, Burchett, Rabeeh, & Ruman, 1997). LCD screens are based on a totally different technology: A steady light source positioned behind the screen is blocked by a layer of liquid crystals arranged in a matrix of pixels. The liquid crystals act as switches that allow the passage of light when a voltage is applied to them. The amount of light transmitted varies with the input voltage. Until recently, LCD screens reacted sluggishly to changes in input voltage. Recent advances in LCD technology, however, have improved their temporal characteristics, making them potential candidates for the laboratory.

Kihara, Kawahara, and Takeda (2010) have shown that observers exhibit comparable performance with CRT and LCD monitors on two well-known attentional and perceptual tasks: the attentional blink and metacontrast masking. As the authors noted, however, these results do not necessarily demonstrate that LCDs are suitable for all experimental paradigms. For instance, because of phosphor persistence, CRT images are known to remain visible for some time after the initial image has been turned off (Di Lollo et al., 1997; Groner, Groner, Müller, Bischof, & Di Lollo, 1993). It is possible that LCD monitors will produce similar residual images as a result of a delay in shifting from one liquid crystal orientation to another. These residual images, which we refer to as display persistence, were not of critical importance in the paradigms investigated by Kihara et al. because the target stimuli were invariably followed by masks that overwrote any lingering persistence on the display screen. On the other hand, residual images are potentially harmful in paradigms that require precise timing of stimulus offset. One of the objectives of the present study was to investigate the duration of display persistence on both CRT and LCD monitors.

An example of this type of confounding can be seen in a study by Jonides, Irwin, and Yantis (1982). The principal objective was to determine whether two sequential images displayed at different retinal locations, but at the same spatial location, could be integrated so as to be perceived as a single image. In other words, Jonides et al. (1982) were interested in determining whether temporal integration can occur spatiotopically. The stimuli were similar to those used in a study by Di Lollo (1977), in which a square 5 × 5 dot matrix was displayed with one dot missing at a randomly chosen location. The observers’ task was to report the matrix location of the missing dot. To study temporal integration, Di Lollo displayed the matrix at fixation in two brief successive frames of 12 dots each, separated by a variable interstimulus interval (ISI). At short ISIs, the two frames were seen as a single integrated image, and the missing dot could be located with ease. At longer ISIs, the two frames were perceived as temporally segregated, and the task was impossible.

This conclusion, however, was vitiated by a considerations of phosphor persistence. The phosphor used in the Jonides et al. (1982) study was P4, which has been shown to generate visible persistence beyond 1 s in dark-adapted viewing (Di Lollo et al., 1997). Given such long phosphor persistence, the dots in the first frame were still visible when the second frame was displayed. Thus, integration of the two frames was mediated not by a visual memory of the dots in the first frame, but by their actual presence on the screen because of phosphor persistence. This was later confirmed by Jonides, Irwin, and Yantis (1983), who used light-emitting diodes that are free from persistence and found no evidence of spatiotopic temporal integration.

Estimates of the visibility—as distinct from the luminance—of display persistence are available for such phosphors as P15 and P31 (e.g., Di Lollo et al., 1997). However, no corresponding estimates are available for the visibility of the persistence of CRT screens commonly used in studies of cognition and perception. The present work provides those estimates.

In the present work, we examined the time course of the visibility of display persistence on both CRT and LCD monitors under light-adapted and dark-adapted viewing. A vertical or horizontal bar was displayed on the monitor behind a closed mechanical shutter. The shutter opened rapidly at varying intervals following the offset of the bar. Therefore, any image still visible on the screen was the result of display persistence. The observers’ task was to identify the bar’s orientation.

A second, and just as important, objective of the present work was to examine the timing of LCD screens. Previous estimates had revealed LCD displays to be sluggish, requiring as long as 150 ms to reach maximum luminance (Liang & Badano, 2007). This slow rise time rendered LCD screens unsuitable for experiments or applications that require brief displays. A recent advance in LCD technology, known as overdrive technology, however, has resulted in substantial reductions in their response times, bringing LCD screens within the range of useful devices.

The principal objective of overdrive technology is to speed the transition from one level of luminance to another, as when a light stimulus is presented on a dark background. Figure 1 illustrates how this is done. Panels a and b show the course of events without overdrive. The two functions in each panel illustrate a shift from a lower level (Level 1) to higher levels (Levels 2 and 3) of intensity. Panel a illustrates changes in the voltages applied to the liquid crystals to achieve and maintain the desired level of luminance. Panel b illustrates the temporal course of the changes in luminance in response to the changes in voltage. Clearly, the sudden increments in voltage (panel a) result in sluggish changes in luminance (panel b). The important thing to note is that the rate of change in luminance is faster for the higher voltage (panel b, segmented line). For example, luminance reaches Level 2 sooner when the voltage is switched to Level 3 than when it is switched to Level 2. This phenomenon is used in overdrive technology to achieve a faster transition between different levels of luminance.

Suppose that the luminance of a stimulus is to be switched rapidly from Level 1 to Level 2. When implementing overdrive, the voltage is initially changed to Level 3 for a single frame, and then lowered to Level 2 (Fig. 1c). The corresponding changes in luminance are illustrated in panel d. Because of the overdrive procedure, the luminance in panel d reaches (and may overshoot) Level 2 within a single frame, as compared to approximately two frames without overdrive (Fig. 1b, solid line). An example of overshoot is seen in Fig. 1d; it occurs when the fast rate of change in luminance associated with the high voltage causes it to exceed the criterial level before the input voltage is reduced to the appropriate level.Part I: Psychophysical estimates of visibility

Stimuli were presented on one of two computer monitors: a 21-in CRT (AccuSync 120 equipped with B22 phosphor, denoted as having “medium-short” persistence, manufactured by NEC: www.necdisplay.com) and a 23-in. LCD (BenQ XL2410T, www.benq.com). B22 phosphor is also known as P22 phosphor. The CRT was set at a resolution of 800 × 600 pixels and the LCD at 1,920 × 1,080 pixels. Both monitors operated at a refresh rate of 120 Hz and were switched on at least 30 min before the beginning of the experiment. The brightness and contrast settings of both display monitors were set to maximum, so as to examine the worst-case scenario for both monitors. The luminance of the stimuli under different viewing conditions is specified below.

Observations were made under two lighting conditions: dark, and ordinary room lighting. The corresponding screen luminance values are specified below. In the dark-viewing condition, the screen was encased within a cover that prevented any screen light from escaping the enclosure. The displays were viewed monocularly with the preferred eye through a mechanical shutter with a 25-mm diameter [Gerbrand Model G1166 (D)/(S)]. The shutter opened from the center out as an expanding circle and was positioned over a small hole in the cover 42 cm from the center of the screen. According to the manufacturer’s specifications, the shutter changes from closed to open in 2 ms. We checked on this with a photodiode and found that the opening delay was close to specification, and never exceeded 4 ms.

The display consisted of a vertical or horizontal light bar presented in the center of a darker background. At the viewing distance of 42 cm, the bar subtended 3.4º × 13.6º (210 × 57 pixels in the CRT monitor, 340 × 90 pixels in the LCD monitor). The orientation of the bar was chosen randomly on each trial, with the constraint that each orientation was chosen an equal number of times.

Each trial began with a 200-ms display of the bar behind a closed shutter. The shutter opened at varying delays following the offset of the bar. In calculating the shutter delays, we took into account the time required for the raster to travel from the top of the screen to the screen location beyond that occupied by the vertical bar. This was done to ensure that the bar had been removed from the screen before the shutter began to open. Given a refresh rate of 120 Hz, the signal to open the shutter was issued 6 ms after the beginning of the raster scan. This was designated as the 0-ms delay. Longer delays were obtained by adding the appropriate temporal intervals. Because of the shutter-opening time, the actual shutter delays were 2–4 ms longer than those shown in the figures. When the shutter opened, the observer attempted to identify the orientation of the bar on the basis of the display persistence remaining on the screen. A total of 48 responses were collected at each combination of lighting condition, monitor, and shutter-opening delay. Stimulus presentation and shutter control were governed by programs written in E-Prime (Version 2.0; Psychological Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

The experiment was conducted in a dark room, and each observer was dark-adapted for at least 30 min prior to the session. The luminance of the white bar on the CRT monitor was 120.0 cd/m2, and the luminance of the black background was 0.2 cd/m2, as measured by a Minolta LS-110 luminance meter. The corresponding luminance values for the LCD screen were 242.1 cd/m2 and 0.2 cd/m2. The range of shutter-opening delays from stimulus offset was set to encompass identification accuracies from near-perfect to near-chance.

The results for the CRT screen, illustrated in Fig. 2, show that the phosphorescence of the CRT screen remained visible (accuracy above 50%) for over 3 s for all observers. Di Lollo et al. (1997) reported similar estimates for P4 and P31 phosphors. In contrast, the display persistence of the LCD screen was negligible, with accuracy hovering around chance even at a nominal shutter delay of 0 (averaged across the three observers, the percentage of correct responses was 49%). We conclude that under dark-adapted conditions, the LCD screen was superior in producing essentially no display persistence, as compared to substantial persistence for the CRT screen.

The above measurements were performed with the brightness and contrast settings of both the CRT and the LCD screens set to maximum. Because these settings resulted in higher luminance for the LCD screen (see above), we replicated the measurements with the luminance of the LCD screen set to match that of the CRT screen. As specified above, the luminance of the CRT was 120.0 cd/m2 for the white bar and 0.2 cd/m2 for the black background. The matching values for the LCD screen were 123.1 cd/m2 and 0.1 cd/m2, respectively. Averaged across the three observers, the percentage of correct responses obtained at the lower luminance setting for the LCD screen was 52%, which was very similar to that obtained at the higher setting. Phenomenologically, the stimuli were never visible on any trial.

The procedures here were the same as in dark-adapted viewing, except that the session was conducted under normal room-lighting conditions. The monitor was not covered with a shield, and participants were not dark-adapted prior to the session. The luminance of the CRT monitor was 123.5 cd/m2 for the white bar and 3.5 cd/m2 for the black background. The corresponding estimates for the LCD monitor were 242.6 cd/m2 for the white bar and 0.8 cd/m2 for the black background. The results for the CRT screen are illustrated in Fig. 3. As expected, the visibility of display persistence was shorter than in dark-adapted viewing (Fig. 2), reaching chance level approximately 125 ms after stimulus offset. Even such relatively short persistence, however, can be harmful when brief exposures are required as in studies of iconic memory and temporal integration. A notable finding was that when the polarity of the displays was reversed (i.e., a black bar on a white background), no persistence was visible even at the shortest shutter delay (averaged across the three observers, the percentage of correct responses at a nominal shutter delay of 0 was 49%).

The results for the LCD screen revealed no display persistence even at the shortest shutter delay for either white-on-black or black-on-white displays (averaged across the three observers, the percentages of correct responses at a nominal shutter delay of 0 were 47% and 49%, respectively). As was done in the dark-adapted viewing condition, a separate set of estimates were obtained for the LCD screen with the luminance set to match that of the CRT. As specified above, the luminance of the CRT was 123.5 cd/m2 for the white bar and 3.5 cd/m2 for the black background. The matching values for the LCD screen were 124.0 cd/m2 and 0.9 cd/m2, respectively. Averaged across the three observers, the percentages of correct responses obtained at the lower luminance setting for the LCD screen were 47% for white-on-black displays and 49% for black-on-white displays. These results were very similar to those obtained at the higher setting. Phenomenologically, the stimuli were never visible on any trial.Part II: Photometric estimates of luminance

Earlier estimates of the time to reach maximum luminance in LCD screens have ranged up to 47 ms for black-to-white transitions (Wiens et al., 2004) and up to 150 ms for gray-to-gray transitions (Liang & Badano, 2007). Those estimates, however, were obtained before the advent of overdrive technology, which boosts the voltage applied to the liquid crystals, thereby markedly improving the temporal response characteristics of LCD screens. The present photometric measurements were performed to assess the extent to which the response times were improved by overdrive technology.

The monitors and the stimuli were the same as those used for the psychophysical estimates. The luminance of the stimuli was measured with a photo diode (S7686, Hamamatsu Photonics) calibrated for the human spectral sensitivity function (spectral response range 480–660 nm, peak sensitivity 550 nm), with an active area of 2.8 × 2.4 mm. The photodiode was placed on the center of the screen, and its output was amplified by a Thorlabs PDA200C photo diode amplifier. The signal was sampled at a rate of 25 kHz by a quickDAQ (Version 1.6.0.8) data acquisition system on a laptop computer via a Data Translation DT9804-EC-I USB Data Acquisition Function Module. In preliminary trials, we found that the LCD display reached maximum luminance within a single 8.33-ms refresh frame. To add a margin of safety, each display consisted of two consecutive frames, for a total display duration of 16.7 ms. A total of 100 such trials, separated by 100-ms gaps, were recorded in the data acquisition system. The average of those 100 trials was then smoothed by means of a central-moving-average procedure using 11 data points, 5 on either side of the point whose mean was to be calculated. The measurements were performed in a dimly lit room.

The results for the CRT screen are shown in Fig. 4, which illustrates transitions from black to white for two successive frames. The zero point on the abscissa represents the vertical sync signal initiating the start of the first frame. Because the stimulus was presented in the center of the screen and the plotting rate was 120 Hz (8.33 ms per frame), the onset of the function is delayed by approximately 4.2 ms from the zero point—to wit, by the time it took the raster scan to reach the center of the screen. Using the criteria specified below in Fig. 6, the rise time and fall time of the left-hand function in Fig. 4 were 320 and 480 μs, respectively. These times are similar to those reported by Westheimer (1993) for P31 phosphor. The duration of a single frame, based on the criteria specified in Fig. 6, was 920 μs. It is perhaps worth noting that the small bumps in the function in Fig. 4 starting just after the 20-ms mark are consistent with similar bumps reported by Kihara et al. (2010, Fig. 1b). Since the frequency of these bumps are in phase with the refresh cycle, they are likely to be produced by electrons shot at the screen while the electron gun is held at a subcritical voltage while the screen is nominally black.

The results for the LCD screen are illustrated in Fig. 5. Estimates were obtained for a black-to-white transition (RGB 0 to 255) and for two gray-to-gray transitions (RGB 10 to 65 and 25 to 165). As was the case for the CRT functions (Fig. 4), the LCD functions in Fig. 5 are delayed by approximately 4.2 ms from the zero point. This was to be expected, on the grounds that, just like CRT monitors, LCD monitors operate on a raster-scan system.

Luminance changes produced by a light bar displayed for two refresh cycles on an LCD screen running at 120 Hz. Three luminance transitions were tested: one black-to-white transition (RGB 0, 0, 0 to 255, 255, 255, labeled as 0–255), and two gray-to-gray transitions (RGB 25, 25, 25 to 165, 165, 165, labeled as 25–165, and RGB 10, 10, 10 to 65, 65, 65, labeled as 10–65). Represented on the ordinate is the strength of the illumination signal (in microvolts) recorded by the photo diode

The functions in Figs. 4 (CRT) and 5 (LCD) differ substantially from one another in maximum intensity (approximately 200 and 14 μV, respectively). As noted in the Method section, the two screens were set to maximum luminance. This resulted in photometric readings of 120.0 and 242.1 cd/m2 for the CRT and LCD screens, respectively. The photometric measures illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, however, exhibit the opposite relationship, with the CRT having the greater intensity. This discrepancy can be understood in terms of the different sampling rates used in the measurements. The luminance values of 120.0 and 242.1 cd/m2 were obtained with a photometer that averaged the screen output over a period of about 1.5 s (~0.67 Hz), whereas the intensity values in Figs. 4 and 5 were obtained with a light sensor that sampled the output every 0.00004 s (25 kHz). The important consideration is that any given pixel in the CRT screen was activated only once per refresh cycle (see Fig. 4), whereas the corresponding pixels in the LCD screen emitted light continuously. To yield similar time-averaged luminances, therefore, the electron beam in the CRT needed to have a higher intensity relative to the backlight of the LCD screen. This difference in intensity is reflected in the functions in Figs. 4 and 5.

A taxonomic survey of commercially available LCD monitors was obviously beyond the scope of the present work. To gain some indication of the generality of the findings reported in the foregoing analysis, however, we tested two additional LCD monitors: a Dell 1907FPc (not equipped with overdrive, released February 2006) and a ViewSonic VS12841 (equipped with overdrive, released December 2009). A further reason for testing additional monitors was to ascertain whether the superior temporal characteristics exhibited by the BenQ XL2410T could be ascribed to the implementation of overdrive technology. The three monitors (Dell, ViewSonic, and BenQ) are compared in Fig. 7. The data were collected as described above, with the following exceptions. The stimuli were displayed for 66.7 ms because preliminary results indicated that all of the monitors reached asymptotic level within this time window. The BenQ monitor was refreshed at a rate of 120 Hz (i.e., the stimuli were displayed for eight frames). Because the Dell and the ViewSonic monitors could not reach a frame rate of 120 Hz, they were run at 60 Hz (i.e., the stimuli were displayed for four frames). In addition, the ViewSonic and the BenQ monitors were run with the overdrive feature either ON or OFF. This could not be done with the Dell monitor, which was not equipped with overdrive.

Luminance changes produced by a light bar displayed for 66.7 ms on three LCD screens. (a) Dell 1907FPc, run at 60 Hz; (b) ViewSonic VS12841, run at 60 Hz; (c) BenQ XL2410T, run at 120 Hz. Three luminance transitions, fully described in the Fig. 5 caption, were tested in each monitor: one black-to-white transition (RGB 0–255) and two gray-to-gray transitions (RGB 25–165 and RGB 10–65). The ViewSonic and the BenQ monitors were tested with the overdrive feature turned ON (bold functions) and OFF (thin functions). Represented on each ordinate is the strength of the illumination signal (in microvolts) recorded by the photo diode

The photometric measurements are illustrated in Fig. 7 and Table 1. Clearly, the response characteristics of both the ViewSonic and BenQ monitors were markedly improved with overdrive turned on. It is also clear that the performance of older models, exemplified by the Dell monitor, is inferior to that of more recent models, even with overdrive in the newer models turned off. All functions in Fig. 7 exhibited some 60-Hz fluctuations, most noticeable in Fig. 7a. Similar fluctuations have been reported by Kihara et al. (2010, Fig. 4c) and by Wiens et al. (2004, Fig. 1b). This 60-Hz component is inherent in the LCD power supply and can be much reduced or eliminated by a 60-Hz notch filter on the power cable, by placing the power supply away from the monitor, or by shielding the main LCD circuit board with a sheet of mu-metal.

Table 1 Rise times, fall times, and durations (in milliseconds) for the BenQ XL2410T, ViewSonic VS12841, and Dell 1907FPc LCD monitors, for three RGB transitions and with overdrive turned OFF or ONGeneral discussion and conclusions

The psychophysical estimates are unambiguous: For white images on a black background, the BenQ LCD screen never produced any display persistence, even in dark-adapted viewing, whereas the CRT produced substantial persistence in both light- and dark-adapted viewing. On the other hand, neither monitor produced any measurable visible persistence for black images on a white background. Clearly, when display persistence is a concern, LCD screens are preferable to CRT screens unless the displays consist of black-on-white stimuli.

As compared to photometric estimates obtained with LCD monitors without overdrive or with overdrive turned off (Fig. 7; see also Liang & Badano, 2007; Wiens et al., 2004), the present estimates highlight the substantial improvement in temporal response characteristics brought about by overdrive technology. For example, our estimated rise time of 1–6 ms is considerably shorter than estimates obtained without overdrive (2–25 ms in our estimates, 20–150 ms in past research; Liang & Badano, 2007; Wiens et al., 2004) and approaches that of CRTs (<1 ms). Clearly, recent advances in LCD technology have resulted in a substantial reduction in response times, making LCD screens suitable for presenting brief displays.

Of the many display monitors available commercially, only one CRT and three LCD monitors were selected for testing in the present work. A complete taxonomy of all available monitors would obviously be unfeasible. Alternatively, one might set out to formulate some general rule relating the photometric characteristics of any given monitor to the manufacturer specifications. However, this calculation would be complicated by the fact that manufacturers use different methods and criteria for assessing the temporal characteristics of their displays.

Then there are the technical words, such as LED TV, LCD TV, QLED TV, UHD TV, OLED TV, and others, that need to be understood. You may need to be a tech expert to play a game with a friend or watch your favorite TV show in the evening.

A lot of people are converting from LCD to LED televisions. The numerous advantages that LED screens provide are the driving force for conversion at most tv repair shops in Lawrence, KS.

First and first, it’s crucial to realize that the LED (Light Emitting Diode) monitor is an adapted form of the LCD (Liquid Crystal Display). Because of this, all LED monitors are, by definition, LCDs; however, not all are LED monitors.

LCD technology changed monitors by using cold cathode fluorescent lamps as backlighting to produce the image displayed on the screen. A small fluorescent bulb is a cold cathode fluorescent light (CCFL). This traditional style of CCFL LCD TVs is referred to as LCDs for this article.

By substituting LED backlighting for fluorescent lighting, LED monitors advanced the existing technology. And the absence of backlighting, thanks to OLED (organic light-emitting diode) technology, makes it even better.

Due to the location of the light source, edge-lit LEDs have a little narrower viewing angle than LCDs. Direct-view LEDs, on the other hand, provide a better viewing angle than LCDs since the light source is dispersed uniformly throughout the display.

LED TVs use less energy than LCD TVs because they use light-emitting diodes instead of fluorescent bulbs. Compared to an LCD screen of the same size, a 32-inch LED TV uses 10 watts less power. As the display size increases, the power consumption difference grows.

This is the amount of time it takes to change colors. Typically, response times are measured in milliseconds. The quality of the images produced improves with the speed of response.

LEDs are far more compact than the fluorescent bulbs used in LCD monitors. The thickness of fluorescent lights is substantial, but that of diodes is virtually nonexistent. The thickness of the array is also unaffected by the number of diodes because they are all arranged in the same plane.

Since LED displays use full-array LED backlighting instead of a single large backlight, LED TVs have a much higher contrast than LCDs. Since LED backlighting can emit the entire RGB spectrum, it can produce a deeper RGB difference than LCD backlighting technology, which can only display white and black.

Moreover, they are more beautiful. What better solution to the growing lack of space in new residential complexes than an ultra-thin LED display that offers a cinematic experience in the comfort of your home?

If you ask tv repair shops in Lawrence, KS, LED screens are the most popular option now among the general public. Everyone is choosing to move from LCD to LED to improve their lives and make them more fun.

We are also a cell phone repair store in Lawrence, KS, data recovery in North Lawrence, KS, electronics repair in Lawrence, KS, and Electronic Recycling Service

If you’re wondering which display will last the longest, LED displays also prevail in this argument. LED televisions have an average lifespan of 50,000 hours compared to LCD televisions, which have a lifespan of 100,000 hours.

The ability to decrease the lighting is one of the eye-comfort advantages of an LED display. Additionally, it offers a broader viewing angle while maintaining the quality of the image. Therefore, compared to an LCD, an LED display is far better for your eyes.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

First, we will provide a brief technical overview of functional principles as they relate to visual stimulus presentation. Detailed descriptions and parameter measurements are already available from the existing literature; however, our intention here is to equip readers with limited technical expertise with the necessary knowledge to set up computer experiments with LCD monitors. Thus, we keep our explanations relatively short and simplified.

LCD monitors work differently: Each pixel consists of liquid crystal threads that can be twisted or arranged in parallel by an electrical current applied to them. This leads to a polarization effect that either allows or prevents light passing through. A white light source located behind this crystal array uniformly and constantly illuminates the array. To display a black pixel, the crystal threads are twisted by 90° such that no light will pass through. A white pixel is achieved by aligning the crystals such that maximum light is allowed to pass through, until a different, non-white color needs to be displayed (see the lower panel of Fig. 1 for an LCD pixel’s brightness over time). This is a static process, not a pulsed one as in CRTs.

In theory, the difference in presentation methods, namely a strobing versus a static image, should be of no consequence if the light energy that falls onto the retina remains the same over the time period of one single frame. As the Talbot-Plateau law states2 is equally well detectable as a light flash presented for 60 ms at 40 cd/m2. This suggests that temporal integration can be easily described by energy summation”. Thus, in principle, LCD and CRT monitors should be able to yield comparable results.

However, due to the differences in technology, the visual signals produced by the two display types have different shapes (i.e., a different light energy-over-time-curve; see Fig. 1). Moreover, default luminance as well as visual-signal response times (in addition to other parameters, see below) differ between most CRT and LCD monitors

Table 1 reports the parameters we considered in setting up the CRT and LCD monitors. Certainly, most of them are commonly considered when setting up a computer experiment; nevertheless we deemed it important to mention them here explicitly, as their neglect might have unintended consequences. We used a 17” Fujitsu Siemens Scenicview P796-2 CRT color monitor previously used in several published studies including studies with masked presentation conditions

We tested various monitor user settings, refresh rates, resolutions and luminance settings (see materials available at https://osf.io/g842s/) with regard to the emitted light energy–over-time-curve and therefore response characteristics (i.e., onset and offset of full screen and centrally presented stimuli). Measurements were conducted with a photodiode setup, using both an oscilloscope (model “Agilent MSOX 3012 A”) and a self-developed microcontroller setup as measurement devices. Stimuli were black and white squares.

Our measurements revealed several interesting characteristics: First, luminance of the LCD monitor at default setting (i.e., maximum brightness) exceeded the CRT luminance at a ratio of 3.25:1. However, comparable average luminance can be (and was) achieved by downregulating the LCD monitor (the older CRT technology emits less energy even at maximum settings, see Table 2), without participants perceiving it as unnaturally dark. If one plans to upgrade from CRT to LCD monitors in an experimental laboratory, we therefore recommend measuring the CRT monitors’ brightness levels and matching them in the new LCD monitors’ user setup, if comparability with the old setup is needed. This will minimize hardware-dependent variability, thus contributing to better replicability. Please note that a brightness adaption is not a necessary precondition when employing LCD monitors; researchers should simply be aware that the brightness level can have an influence onto the resulting effects, especially in time-critical experiments with short and/or masked presentation. Thus, we recommend the adaptation for time-critical experiments in which researchers orient on existing empirical evidence gathered with CRT monitors. Furthermore, gray-to-gray response times varied slightly depending on the employed brightness levels2), so we suggest that researchers can rely on this more efficient method as an approximation.

For the empirical comparison of human performance with CRT and LCD monitors, we relied on these results and set the monitor settings accordingly (see Method section below).

Participants were administered a masked number priming task and a subsequent forced-choice prime discrimination task using both a CRT and an LCD monitor. In this well-established paradigm

Of central interest was the question whether both monitors would yield comparable masked priming effects. Monitors were set according to the parameters described in the previous section (see also Method section below). In order to obtain conclusive evidence, we decided for sequential hypothesis testing using Bayes factorshttps://osf.io/g842s/.

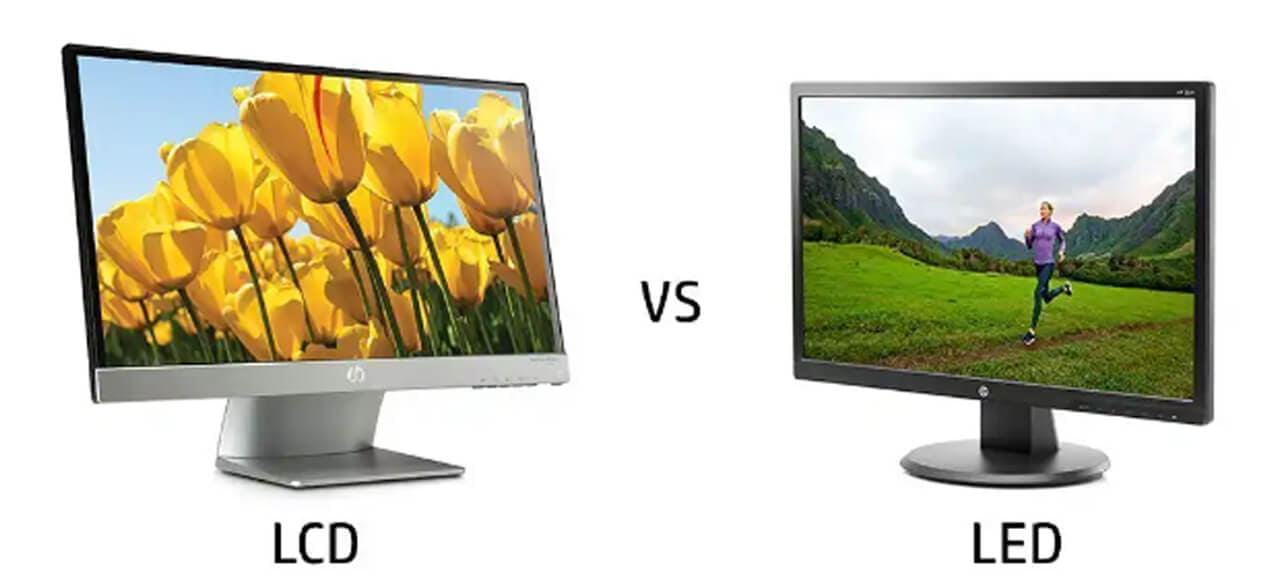

LCD monitors have been around longer, so they’re more affordable. However, LED monitors are more energy-efficient, lighter and support 4K resolutions.

LCDs feature a layer of liquid crystal embedded between two panels. Images are created when fluorescent lamps behind the screen shine through the crystals and illuminate them.

There are various types of backlights used in LCD monitors, but the most common is cold cathode fluorescent lamps. Essentially, the lights used for CCFL displays are akin to those you see in offices, classrooms and stores, except much smaller.

The first few generations of LCD monitors and televisions used this type of backlight and while you can still find LCD monitors with this backlight, it"s becoming less and less common.

Since it’s an older technology, LCD monitors are generally much cheaper than LED monitors. However, despite being less advanced, they still provide a high-quality image. They’re also better suited for brighter environments like living rooms and kitchens since they provide an overall brighter image.

LCD monitors are also less prone to suffer from burn-in image issues. Burn-in refers to an image becoming “stuck” on the screen. This can happen if a static image is left displaying on the screen for too long. Image retention is more likely to happen if you’re a gamer since some video games feature heads-up display elements that rarely move out of place.

Because of the backlight, LCD monitors are bulkier and thicker than LED monitors. They’re also much less energy-efficient due to the energy required to power the fluorescent lamp backlight.

Finally, you’ll get a crisp 1080p high-definition resolution using an LCD monitor, but if you plan to stream 4K content, it’s best to steer clear from them as most LCDs don’t support 4K.

An LED monitor is also an LCD monitor since it also uses a liquid-crystal screen. However, this specific type of display where the backlight is composed of light-emitting diodes instead of fluorescent lamps. You can imagine light-emitting diodes as a series of tiny light bulbs.

Most LED displays feature edge lighting, which means that the LEDs are positioned around the edge of the screen. Some LED displays have a wide-array setup where the LEDs are placed all over the screen.

The overall image quality of an LED monitor is superior as well. Producing true black contrasts is an issue with LCDs due to the type of backlight, but LED screens reduce this problem significantly.

LED displays also have a fast refresh rate and low lag, which makes them ideal for gamers. Also, unlike with older LCD monitors, you’ll be able to stream 4K content.

Since LED monitors are the newer technology, they’re considerably more expensive than LCD monitors. There’s also a higher risk of image retention with LED displays.

Although the initial price point of an LED monitor is higher, they’re more energy-efficient and have a longer lifespan. You’ll end up saving money in the long run, which makes it a much better investment than an LCD screen.

A video wall is not a one-size-fits-all solution. There are many options to choose from when designing a commercial building video wall display: the size and shape of the digital canvas, what type of content will be displayed and the purpose of the video wall. Operationally, you may focus on desired reliability, maintenance and serviceability of the equipment. Hardware and technology decisions ensure the video wall will deliver both the desired viewing and ownership experience.

One of these choices is deciding between an LCD display or an LED video wall. Continue reading to find out more about the basics, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each solution.

Most people are familiar with LCD technology, which stands for Liquid Crystal Display. These types of displays have a massive presence in this world, used in living rooms to watch movies, fast-food restaurants to showcase menus, airports to show flight schedules, and everything in between. LCD technology was developed in the 1960s and has been used worldwide as a standard for roughly 20 years. It is a tried-and-true technology that has stood the test of time and will be around for the foreseeable future.

On an LCD screen, the panel is illuminated by a light source and works through reflection or transmission of light. Overall, LCD displays have better viewing angles and less glare than LED screens. This technology was designed to be energy efficient and tends to be lighter in weight.

An LCD video wall is made up of multiple LCD panel monitors mounted on a surface to create a digital canvas, which then work together to create a unified experience. They operate 24/7 at a high brightness and have thin bezels that help create a seamless look when the displays are placed next to one another.

Bezel thickness and the brightness rating are among key attributes to consider for an LCD video wall display. Here is what each of these means and why.

Bezel:Bezel thicknesses for video wall displays are measured in “bezel-to-bezel” thickness.This is the thickness of the bezel when two displays are placed next to one another. Displays can be either large bezel or thin bezel.

Nits:Brightness is measured in Nits. A higher Nit value means the display will be brighter. A brighter display is necessary in a room that sees plenty of direct sunlight, or if the intent is to draw in visitors from far away. With LCD video walls, the price of the hardware goes up as the display size and brightness increase, and the bezel width decreases.

The next item to consider is the type of content that will be displayed on your video wall. LCD displays have high resolution screens — modern 4K displays have over 8 million pixels! This means that the content being displayed is highly detailed and crystal-clear. A viewer could stand less than 1 foot away from the screen and be able to see exactly what is being shown on the screen.

Like previously mentioned with LCD video walls, an important consideration in the decision-making process is the type of content that will be displayed on the video wall. LED video walls suffer from image degradation and pixilation from up close, so fine details will be lost, and text will be illegible. If detail from up close is important, LCD displays are much better suited for that situation.Content examples that are well-suited for an LCD video wall:

Video walls are relatively new. But LCD technology has had decades of mainstream adoption, and with that comes both familiarity and lower costs. If those are important to you, then an LCD video wall is likely the right choice.

LED video walls are similar to LCD video walls, but the digital canvas is built using LED panels. Individual LED panels can be anywhere from 12”x12” to 36”x18”, which is much smaller than LCD displays. LED panels have a larger presence in this world than most might think—they are found indoors and outdoors at stadiums, arenas, concert venues, airports, and in use as large digital advertisements in iconic places such as Times Square.

The module is a small rectangular board that contains all the individual LEDs (light-emitting diodes).Unlike LCD, there is no glass or color filter on the LED video wall panels. The individual diodes that are placed on the modules produce both color and light.

One of the most impressive features of LED panels is that they can be combined to create almost any shape, without a bezel interrupting the digital canvas. LED video wall panels can be placed on curved surfaces, 90-degree edges, and other non-standard surfaces. The smaller size of the panels in relation to LCD video wall displays means they can fill more space on a surface—they aren’t limited to standard 46” and 55” sizes as are LCD video wall displays.

The most important factor to consider when scoping LED panels for a video wall is what is referred to as “pixel pitch.” The pixel pitch is effectively the distance between each pixel on the LED panel—a pixel pitch of 6mm means each pixel is spaced 6 millimeters away from the adjacent pixel. The smaller the pixel pitch, the smaller the distance is between each pixel, which means there are more pixels per square inch on the digital canvas.

Pixel pitch factors into viewing distance. When the pixels are close together, the image is more detailed and can be viewed comfortably by others from a close distance. But when the pixels are spaced further apart, a viewer needs to stand further away to view the image clearly.

Lastly, pixel pitch impacts the price of the LED video wall more than any other factor. For example, a 2mm pixel pitch LED video wall costs significantly more than its 10mm pixel pitch counterpart.

As is the case with an LCD video wall, an LED video wall will add exciting drama and premium value to showcase spaces. LED panel displays don’t enjoy the benefit of decades of mainstream adoption as do their LCD counterparts. However, the technology curve is increasing their availability and lowering their costs. At this time, an LED video wall will have higher upfront costs compared to an LCD video wall. If cost is the main concern, then an LED video wall system will not likely fit into your budget

Aside from LED video wall cost, there are other factors to consider which could make an LED video wall system the frontrunner for your project. Here are the advantages and disadvantages to consider:

Limitless shapes and sizes:the smaller size of LED panels allows them to be combined to create unique canvases, including curved, 90-degree edge, and other combinations not possible with LCD displays

Easy maintenance and service; high reliability:LED module replacement takes seconds with little effort; LED panels are rated with a lifetime of 80,000-100,000 hours, depending on the product

Video wall systems come in all shapes and sizes. The components used to create the video wall experience vary widely. Consider variables other than video wall cost when scoping out both the content and the hardware. Because these parts and pieces could make or break the captive viewing experience you’re hoping to achieve, or worse, defeat the entire purpose of that video wall.

So if you’re looking to buy a video wall in the next year, talk to us about your plans. We’ll discuss your goals and options to determine what digital video wall package and digital directory elements are right for you. Contact us today to get a free video wall consultation.

For all the new technologies that have come our way in recent times, it’s worth taking a minute to consider an old battle going on between two display types. Two display types that can be found across monitors, TVs, mobile phones, cameras and pretty much any other device that has a screen.

In one corner is LED (light-emitting diode). It’s the most common type of display on the market, however, it might be unfamiliar because there’s slight labelling confusion with LCD (liquid crystal display).

For display purposes the two are the same, and if you see a TV or smartphone that states it has an ‘LED’ screen, it’s an LCD. The LED part just refers to the lighting source, not the display itself.

In a nutshell, LED LCD screens use a backlight to illuminate their pixels, while OLED’s pixels produce their own light. You might hear OLED’s pixels called ‘self-emissive’, while LCD tech is ‘transmissive’.

The light of an OLED display can be controlled on a pixel-by-pixel basis. This sort of dexterity isn’t possible with an LED LCD – but there are drawbacks to this approach, which we’ll come to later.

In cheaper TVs and LCD-screen phones, LED LCD displays tend to use ‘edge lighting’, where LEDs sit to the side of the display, not behind it. The light from these LEDs is fired through a matrix that feeds it through the red, green and blue pixels and into our eyes.

LED LCD screens can go brighter than OLED. That’s a big deal in the TV world, but even more so for smartphones, which are often used outdoors and in bright sunlight.

Brightness is generally measured as ‘nits’ – roughly the light of a candle per square metre. Brightness is important when viewing content in ambient light or sunlight, but also for high dynamic range video. This applies more to TVs, but phones boast credible video performance, and so it matters in that market too. The higher the level of brightness, the greater the visual impact.

Take an LCD screen into a darkened room and you may notice that parts of a purely black image aren’t black, because you can still see the backlighting (or edge lighting) showing through.

You’ll often see a contrast ratio quoted in a product’s specification, particularly when it comes to TVs and monitors. This tells you how much brighter a display’s whites are compared to its blacks. A decent LCD screen might have a contrast ratio of 1,000:1, which means the whites are a thousand times brighter than the blacks.

Contrast on an OLED display is far higher. When an OLED screen goes black, its pixels produce no light whatsoever. That means an infinite contrast ratio, although how great it looks will depend on how bright the screen can go. In general, OLED screens are best suited for use in darker rooms, and this is certainly the case where TVs are concerned.

OLED panels enjoy excellent viewing angles, primarily because the technology is so thin, and the pixels are so close to the surface. You can walk around an OLED TV or spread out in different spots in your living room, and you won’t lose out on contrast. For phones, viewing angles are extra important because you don’t tend to hold your hand perfectly parallel to your face.

Viewing angles are generally worse in LCDs, but this varies hugely depending on the display technology used. And there are lots of different kinds of LCD panel.

Perhaps the most basic is twisted nematic (TN). This is the type used in budget computer monitors, cheaper laptops, and very low-cost phones, and it offers poor angled viewing. If you’ve ever noticed that your computer screen looks all shadowy from a certain angle, it’s more than likely it uses a twisted nematic panel.

Thankfully, a lot of LCD devices use IPS panels these days. This stands for ‘in-plane switching’ and it generally provides better colour performance and dramatically improved viewing angles.

IPS is used in most smartphones and tablets, plenty of computer monitors and lots of TVs. It’s important to note that IPS and LED LCD aren’t mutually exclusive; it’s just another bit of jargon to tack on. Beware of the marketing blurb and head straight to the spec sheet.

The latest LCD screens can produce fantastic natural-looking colours. However, as is the case with viewing angles, it depends on the specific technology used.

OLED’s colours have fewer issues with pop and vibrancy, but early OLED TVs and phones had problems reining in colours and keeping them realistic. These days, the situation is better, Panasonic’s flagship OLEDs are used in the grading of Hollywood films.

Where OLED struggles is in colour volume. That is, bright scenes may challenge an OLED panel’s ability to maintain levels of colour saturation. It’s a weakness that LCD-favouring manufacturers enjoy pointing out.

Both have been the subject of further advancements in recent years. For LCD there’s Quantum Dot and Mini LED. The former uses a quantum-dot screen with blue LEDs rather than white LEDs and ‘nanocrystals’ of various sizes to convert light into different colours by altering its wavelength. Several TV manufacturers have jumped onboard Quantum Dot technology, but the most popular has been Samsung’s QLED branded TVs.

Mini LED is another derivation of LED LCD panels, employing smaller-sized LEDs that can emit more light than standard versions, increasing brightness output of the TV. And as they are smaller, more can be fitted into a screen, leading to greater control over brightness and contrast. This type of TV is becoming more popular, though in the UK and Europe it’s still relatively expensive. You can read more about Mini LED and its advantages in our explainer.

OLED, meanwhile, hasn’t stood still either. LG is the biggest manufacturer of large-sized OLED panels and has produced panels branded as evo OLED that are brighter than older versions. It uses a different material for its blue OLED material layer within the panel (deuterium), which can last for longer and can have more electrical current passed through it, increasing the brightness of the screen, and elevating the colour volume (range of colours it can display).

Another development is the eagerly anticipated QD-OLED. This display technology merges Quantum Dot backlights with an OLED panel, increasing the brightness, colour accuracy and volume, while retaining OLED’s perfect blacks, infinite contrast and potentially even wider viewing angles, so viewers can spread out anywhere in a room and see pretty much the same image. Samsung and Sonyare the two companies launching QD-OLED TVs in 2022.

And for smartphones there’s been a move towards AMOLED (Active-Matrix Organic Light Emitting Diode) screens for Android screens, while Apple has moved towards OLED for its smartphones and tried Mini LED with its iPad Pro. Technologies are consistently evolving with Superand Dynamic AMOLED versions available, more performance is being eked out.

While LED LCD has been around for much longer and is cheaper to make, manufacturers are beginning to move away from it, at least in the sense of the ‘standard’ LCD LED displays, opting to explore the likes of Mini LED and Quantum Dot variations.

OLED has gained momentum and become cheaper, with prices dipping well below the £1000 price point. OLED is much better than LED LCD at handling darkness and lighting precision, and offers much wider viewing angles, which is great for when large groups of people are watching TV. Refresh rates and motion processing are also better with OLED though there is the spectre of image retention.

If you’re dealing with a limited budget, whether you’re buying a phone, a monitor, a laptop or a TV, you’ll almost certainly end up with an LCD-based screen. OLED, meanwhile, incurs more of a premium but is getting cheaper, appearing in handheld gaming devices, laptops, some of the best smartphones as well as TVs

Which is better? Even if you eliminate money from the equation, it really comes down to personal taste. Neither OLED nor LCD LED is perfect. Some extol OLED’s skill in handling darkness, and its lighting precision. Others prefer LCD’s ability to go brighter and maintain colours at bright levels.

How do you decide? Stop reading this and go to a shop to check it out for yourself. While a shop floor isn’t the best environment in which to evaluate ultimate picture quality, it will at least provide an opportunity for you to realise your priorities. Whether you choose to side with LCD or OLED, you can take comfort in the fact that both technologies have matured considerably, making this is a safe time to invest.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey