display screens for memory impared quotation

In the MIS, patients are given a sheet of paper with the names of four items (an animal, a vegetable, a city, and a musical instrument). The paper is taken away after the patient reads the items aloud. The patient is then asked to recall an item from each category (e.g., “What was the vegetable?”). After a brief delay, during which the patient counts from one to 20 and back, the patient is asked to name all of the items. If the patient misses an item, the examiner cues the patient with the category (e.g., “What was the vegetable?”). The patient receives two points for each item recalled without cueing, and one point for each item recalled with cueing (maximum score of 8 points). In a study of 483 community-dwelling older adults, a cutoff of 5 points or less was 86 percent sensitive and 91 percent specific for dementia (LR+= 9.6, LR– = 0.15), and was 92 percent sensitive and 91 percent specific for Alzheimer dementia (LR+ = 10.2, LR– = 0.09).

Answer: You administer the Mini-Cog screening instrument for dementia. The patient can only recall one out of three items, places most of the numbers correctly on the right side of the clock, and incorrectly places the clock hands. Because she recalled only one out of three items and the result of her clock drawing test was abnormal, she screens positive for dementia. You perform a full evaluation for dementia, including a more detailed interview, to confirm the diagnosis and an assessment for secondary causes.

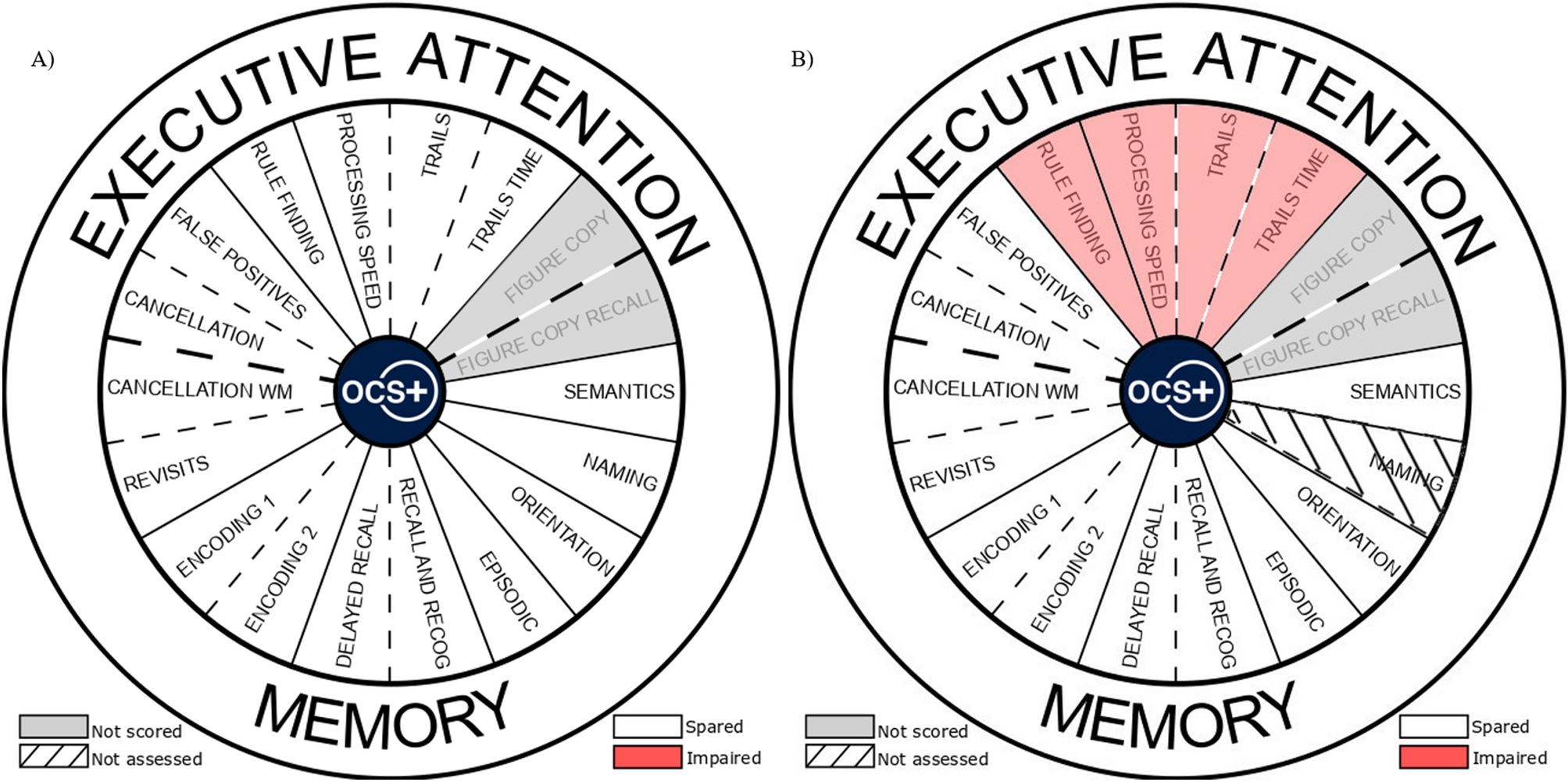

Dementia involves progressive and often remorseless decline in cognition, function, behaviour and care needs. Assessment in dementia relies on collateral as well as patient-derived information. Many assessment scales have been developed over decades for use in dementia research and care. These scales are used to reduce uncertainty in decision making, for example in screening for cognitive impairment, making diagnoses of dementia and monitoring change. Ideal scales used in dementia should demonstrate face validity and concurrent validity against gold standard assessments, should be reliable, practical, and should rely on objective rather than subjective information. Assessment scales in the domains of cognition, function, behaviour, quality of life, depression in dementia, carer burden and overall dementia severity are reviewed in this article. The practical use of these scales in clinical practice and in research is discussed.

Dementia is a term for a clinical syndrome characterized by progressive acquired global impairments of cognitive skills and ability to function independently. Many patients show varying levels of behaviour disturbance at some point in the illness. Care burden, for family carers as well as state/other care funders, increases as the condition progresses. The syndrome is caused by many diseases, with Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies together accounting for around 90% of cases. Incidence and prevalence of dementia are strongly age dependent. With global aging of populations, dementia prevalence is rising and is projected to continue to do so for much of the present century. The collateral damage in dementia is vast. Carer burden in terms of physical work, psychological distress and financial obligations is great. Many nonspecialist branches of medicine now operate some system for screening for and diagnosing dementia – for example, primary care, neurology or general hospital inpatient services. Rating scales are often advocated for use in influential guidelines [NICE, 2006].

A vast industry in generation, validation and reporting of properties/utility of rating scales in most branches of medicine, including dementia, has emerged. Many scales have been devised just in the field of dementia [Burns et al. 2002]. The purpose of an assessment scale is to increase the precision of a decision by reducing subjectivity and increasing objectivity; for example, using a cognitive screening test score to screen for underlying dementia, to distinguish impairment due to dementia from normal age-related cognitive change or to monitor the effects of treatment of dementia in a clinic or controlled trial. The properties of an ideal assessment scale would be that it is valid, that is, it has face validity (experts like clinicians, patients and carers would agree that the questions are relevant and important), that it has construct validity (it measures the construct it was designed to measure), concurrent validity (when used alongside a gold standard assessment like a very well validated scale or an expert clinical assessment, it performs well), that it shows reliability – typically inter-rater reliability (two or more raters using the scale in the same subjects and conditions come up with the same result) and test–retest reliability (the same rater using the scale on another occasion in the same subject comes up with the same result). Importantly, it should be practical to use – in practice, this often depends on it being short (so it can be used in busy clinical practice or as an outcome measure in a trial such that participants are not overburdened by long interviews) and acceptable – so it does not upset, exhaust or embarrass the patient or assessor. The key task in using assessment scales in dementia (as in any field) is clarifying what they are to be used for, and by whom. Scales are frequently misunderstood and misused, wasting patients’, carers’ and assessors’ time. Another aspect of dementia which distinguishes it from other progressive neurological disorders is the increased reliance on others to assess clinical and practical problems. Dementia may from its earliest stages affect judgement, speech and memory, making patient judgements less reliable. Proxies such as family or professional carers need to be consulted at all stages in the care journey, altering the traditional assessment method to a shared patient/carer encounter (for example, the combination of a patient-facing cognitive assessment with a structured or unstructured informant interview in diagnosing dementia). This is directly relevant to the choice of assessment scales to be used in dementia care and research. In particular, judgements about functional impairment, quality of life and behaviour problems may have to be mainly, or entirely, derived from proxy reports.

In clinical practice and in research, cognition is considered the key change we want to observe in people with dementia. Diagnostic criteria for dementia depend on the presence of cognitive impairment [APA, 2000], and other aspects of the clinical picture in dementia (behaviour, impairment in function, increased costs, carer stress) ultimately derive from impaired cognition. Function refers to abilities to carry out activities of daily living, a direct consideration at the point of diagnosis of dementia [APA, 2000] and also in assessing change and planning care interventions. Behaviour changes seen in dementia, often referred to as Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD) are of special importance in influencing prescribing (often hazardous), institutionalization of patients and carer stress. Proper evaluation of interventions for BPSD can only be carried out using reliable scales. Quality of life (QOL) is a multidimensional concept which reflects the patient’s perception of the effect of their illness on their everyday physical and emotional functioning. Measurement of QOL is increasingly popular. In dementia, subjective evaluations are frequently impossible, and patients and carers have very different ratings of QOL. Scales for measuring QOL include patient and proxy versions, and generic and dementia-specific scales. Depression is common in dementia; rating this fundamentally subjective experience is especially challenging in patients with cognitive impairment. Carer burden is a major issue in dementia; service- and research-level interventions may look to measure effects on carers using generic measures of psychological distress or measures designed specifically to measure carer burden. Overall dementia severity assessments are designed to assign a level of severity to a patient’s condition, and are especially useful in assorting cases in research or service development. This paper considers scales used for each of these areas.

Scales in this section are included as they are used in clinical or research settings to screen for dementia, are brief (under 30 min), involve professionals interacting with patients and have been either recommended in reviews or guidelines [Brodaty et al. 2006; Holsinger et al. 2007; Milne et al. 2008; Appels and Scherder, 2010], or widely reported. Psychometric properties for each scale are summarized in Table 1. It should be noted that single cutoffs are never clearly best on any screening scale – those quoted have good combinations of sensitivity and specificity.

ACE-R, Addenbrookes Cognitive Assessment – Revised; AMTS, Abbreviated Mental Test Score; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder; GPCOG, General Practitioner assessment of Cognition; MIS, Memory Impairment Screen; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TYM, Test Your Memory.

The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) [Qureshi and Hodkinson, 1974] is a 10-item scale derived from a longer scale introduced previously [Hodkinson, 1972]. Any clinician can use this, and it takes only 3–4 min. It assesses orientation, registration, recall and concentration, and scores of 6 or below (from maximum of 10) have been shown to screen effectively for dementia, though as with many brief screens, low positive predictive values mean a second-stage assessment is always necessary [Antonelli Incalze et al. 2003]. Its brevity and ease of use have made it popular as a screening test in primary and secondary care nonspecialist settings.

Numerous versions of the clock-drawing test have been devised, with many scoring algorithms [Brodaty and Moore, 1997]. Patients are typically asked to draw a clock face with numbers and hands (indicating a dictated time). It was designed as a quick and acceptable screening test for dementia. It is fast, requires no training and most scoring methods are fairly simple. It shows fairly good sensitivity and specificity as a screening test. It assesses only a very narrow part of cognitive dysfunction seen in dementia, and many other conditions (e.g. stroke) will affect it directly.

The Mini-Cog [Borson et al. 2000] is a very short test (3 min) suitable for primary care screening for dementia. It incorporates the clock-drawing test, adding a three-item delayed word recall task. It showed comparable sensitivity and specificity to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in classifying community cases of dementia [Borson et al. 2003].

The 6-CIT [Brooke and Bullock, 1999] was designed for screening in a primary care setting. It takes 3–4 min to administer, and scoring is between 0 and 28, with cutoffs of 7/8 showing good screening sensitivity and specificity. It is easy to administer, though scoring is less intuitive than AMTS.

The Test Your Memory [Brown et al. 2009] test is a recently developed 10-item cognitive test designed to be self-administered under medical supervision. The maximum score is 50; at a score of 30 or below, the test has good specificity and sensitivity [comparable to MMSE and Addenbrookes Cognitive Assessment – Revised (ACE-R)] in distinguishing dementia from nondementia cases [Hancock and Larner, 2011]. This form of test may be attractive for time-limited clinicians wanting to screen for dementia, especially in primary care.

The General Practitioner assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) [Brodaty et al. 2002] was designed for use in primary care and includes nine direct patient cognitive items, and six informant questions assessing change over several years. In total, it takes about 6 min. It has strong performance on sensitivity and specificity versus MMSE in detecting dementia in a typical primary care population [Ismail et al. 2009].

The Memory Impairment Screen is a very brief four-item scale taking under 5 min to administer, and showing good sensitivity and specificity in classifying dementia [Buschke et al. 1999]. It lacks executive function or visuospatial items. Its use is likely to be confined to primary care, as an alternative to GPCOG, 6-CIT, clock-drawing, Mini-Cog or AMTS.

The MMSE [Folstein et al. 1975] is by some way the best known and most widely used measure of cognition in clinical practice worldwide. This scale can be easily administered by clinicians or researchers with minimal training, takes around 10 min and assesses cognitive function in the areas of orientation, memory, attention and calculation, language and visual construction. Patients score between 0 and 30 points, and cutoffs of 23/24 have typically been used to show significant cognitive impairment. It is widely translated and used. A standardized version [Molloy et al. 1991] improves its reliability, and is probably most important for research settings. The MMSE is unfortunately sometimes misunderstood as a diagnostic test, when it is in fact a screening test with relatively modest sensitivity. It has floor and ceiling effects and limited sensitivity to change. This in theory should limit its wider use in detecting change in clinical work and in research studies, though in these contexts it is still widely used, and even advocated [NICE, 2006].

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment [Nasreddine et al. 2005] was originally developed to help screen for mild cognitive impairment (MCI). It takes minimal training and can be used in about 10 min by any clinician. It assesses attention/concentration, executive functions, conceptual thinking, memory, language, calculation and orientation. A score of 25 or lower (from maximum of 30) is considered significant cognitive impairment. It performs at least as well as MMSE, including in screening for dementia. It has been widely translated. As it assesses executive function, it is particularly useful for patients with vascular impairment, including vascular dementia.

The ACE [Mathuranth et al. 2000] and its commonly used revision the ACE-R [Mioshi et al. 2006] was originally developed as a screening test for dementia which, unlike the MMSE, would rely less on verbal than on executive abilities. It takes 15–20 min to administer and includes the items which lead to a MMSE score. It has been shown to have very high reliability and excellent diagnostic accuracy, and it is a practical option for clinical services intent on precision in diagnoses.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive section (ADAS-Cog) [Rosen et al. 1984] is a detailed cognitive assessment for dementia, and takes a trained interviewer about 40 min to administer. It covers all cognitive areas in dementia and has good sensitivity to change.

The length of the assessment makes it generally unsuitable for clinical settings, but it is included as it is the leading assessment of cognitive change in drug trials in dementia, with a four-point difference between treatment groups considered clinically important [Rockwood et al. 2007].

The Cambridge Assessment of Memory and Cognition [Roth et al. 1986] is the cognitive section of the comprehensive CAMDEX assessment. It covers a range of cognitive functions, including orientation, language, memory, attention, praxis, calculation, abstract thinking and perception. It takes around 25–40 min for a clinician to administer and requires a modest degree of training. It performs well against MMSE with no ceiling effects and conventional cutoffs of 79/80 have demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity for dementia [Huppert et al. 1995]. Its combination of breadth and relative brevity make it suitable for clinical use, particularly new assessments of patients in memory clinics. It has the added advantage of including questions to generate an MMSE score.

The Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS) [Bucks et al. 1996] was designed specifically for use in patients with dementia and covers 20 daily living activities. It takes a carer (professional or family) 15 min to administer. It is sensitive to change in dementia and short enough to use in clinical practice (carers may fill it in while clinicians are performing direct assessment of patients). It is regularly used as an outcome measure in clinical trials, where it is world leading as a dementia-specific measure. This outcome is among those recommended by a consensus recommendation of outcome scales for nondrug interventional studies in dementia [Moniz-Cook et al. 2008].

The Barthel index [Mahoney and Barthel, 1965] is probably the best known assessment of functional ability for older people. It takes 5 min of informant’s time and has been widely translated and validated. It focuses on physical disability in 10 domains and should not be used other than to assess physical functional deficits in people with dementia, among whom cognitive deficits tend to confound assessment.

The Functional Independence Measure [Keith et al. 1987] measures overall disability. It is observer rated and covers multiple important domains, including self-care, sphincters, mobility, communication, psychosocial function and cognition. Some training is required for its use. A UK version is available and it has been used in repeated observations of inpatients in general hospital [Zekry et al. 2008]. It is therefore an example of a scale which addresses cognitive as well as physical function, and is likely to be especially useful in inpatient or rehabilitation settings.

The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale [Lawton and Brody, 1969] takes 5 min for a basically trained interviewer to assess ability in eight complex daily living tasks such as telephone use, shopping, housekeeping and finances. These abilities are more complex than the more basic abilities assessed by the Barthel scale, and therefore more sensitive to the cognitive changes seen in dementia. It is very commonly used in European memory clinics [Ramirez-Diaz et al. 2005].

The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) [Jorm and Jacomb, 1989] is a questionnaire administered to an informant outlining changes in everyday cognitive function. It aims to establish cognitive decline independent of premorbid ability by concentrating on 16–26 (depending on version) functional tasks, including recall of dates/conversations/whereabouts of objects, handling finances and using gadgets. It takes about 10 min to administer, and is conventionally used at the assessment stage in diagnosing dementia, usually combined with a direct cognitive assessment of the patient. This combination increases accuracy of diagnoses versus cognitive assessment alone [Jorm, 1994]. It is therefore suitable as a screening tool rather than in assessing change in function.

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory [Cummings et al. 1994] assesses a wide range of behaviours seen in dementia for both frequency and severity. These include delusions, agitation, depression, irritability and apathy. The scale takes 10 min for a clinician to administer to a carer. It has good psychometric properties and is widely used in drug trials, while being short enough (especially with patients without a wide range of behavioural issues) to consider for use in clinical practice.

The Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory [Cohen-Mansfield, 1986] takes 15 min for carers to rate, but requires some training. Up to 29 behaviours seen in dementia are rated for frequency – the lack of focus on severity is corrected by the breadth of behaviours covered. The behaviours covered include many of those found most disruptive, including verbal aggression, repetitiveness, screaming, hitting, grabbing and sexual advances. It is most commonly used in research settings.

The BEHAVE-AD [Reisberg et al. 1987] takes 20 min for a clinician to use, and is therefore most commonly used in interventional research studies. It covers most of the important disruptive behaviours, including aggression, overactivity, psychotic symptoms, mood disturbances, anxiety and day/night disturbances. Respondents are asked about the presence of behaviours and how troubling they are. It is reliable, sensitive to change and to stage of disease.

The EuroQol measure [EuroQol Group, 1990] is a short, freely available generic measure of health-related quality of life. It can be simply administered to patients or carers in the form of a very brief self-completed questionnaire. There are two core components to the instrument: a description of the respondent’s own health using a health state classification system with five dimensions, and a rating on a visual analogue thermometer scale. It takes 2 min to complete. Like many quality of life instruments, carer and proxy ratings diverge widely, many patients with dementia cannot fill out the instrument, and the chief use of EuroQoL in dementia is as a health utility measure for measuring the economic impact of interventions in trials.

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) [Ware and Sherbourne, 1992] and its shorter descendant the SF-12 [Ware et al. 1996] are examples of generic measures of quality of life which use recall over particular periods of time (typically 1 or 4 weeks) and are used to estimate health burden in large populations. These instruments have been shown to have high rates of noncompletion among frail older people and especially among those with moderate to severe dementia. They may have limited use for carers of people with dementia, but probably cannot routinely be used in practice with patients.

The Alzheimer’s Disease-related Quality of Life scale (QoL-AD) [Logsdon et al. 1999] is a 13-item scale which has been extensively validated, is disease specific, can be completed by patient or carer and is suitable for use across the range of severity of dementia [Hoe et al. 2005]. It takes 10–15 min to administer. Patient and proxy versions are available. In a controversial area, its disease- specific properties, along with those of the health-related quality of life in dementia instrument (DEMQOL), make it a leading choice if quality of life is to be assessed [Moniz-Cook et al. 2008].

DEMQOL [Smith et al. 2007] is a 31-item, disease-specific instrument for evaluating health-related quality of life in dementia, which shows comparable psychometric properties to the best available instruments and has been validated in a UK population. It has both patient-completed and proxy forms. Like QoL-AD, it is primarily likely to be used in research studies.

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [Yesavage et al. 1983] is the most commonly used assessment of depressed mood among older people, and has been shortened to numerous versions, including a popular 15-item version (GDS-15) [Sheikh and Yesavage, 1986]. GDS-15 is usually self rated though can be rated by an assessor. It is sensitive to change and is reliable in older people in institutional care. It takes about 5–10 min to administer. Its major drawback in dementia is that it has been validated for people with mild dementia, but not for those with moderate to severe dementia (among whom completion rates may be low due to difficulty comprehending questions).

The Cornell Scale [Alexopoulos et al. 1988a] is a 19-item scale in which questions are asked of the patient and the carer, meaning that the patient does not need to be able to answer questions for it to be used. The maximum score is 38. It has been validated patients with and without dementia [Alexopoulos et al. 1988b]. In patients with dementia, it is considered the gold standard for quantifying depressive symptoms.

The Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [Montgomery and Asberg, 1979] takes about 15–20 min for a trained assessor to complete. It is useful among older patients in that mainly psychological rather than confounding physical symptoms are assessed. It is particularly sensitive to change and often used in interventional research but the same issues as with GDS will limit its usefulness outside mild dementia.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [Hamilton, 1960] is one of the most commonly used depression rating scales. It requires 20–30 min of questions in a semi-structured interview by a trained interviewer, and is therefore unlikely to be used in people with dementia. It is commonly used in antidepressant drug trials, and like MADRS, has a preponderance of psychological rather than physical items.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [Zigmond and Snaith, 1983] is a popular screening test for depression and anxiety which was originally aimed at patients in hospital, though it has been used much more widely in recent years. It takes 3–5 min and is self-reported. Though easy to use and accurate at detecting depression, it has little practical use for older patients with significant cognitive impairment.

The General Health Questionnaire, 12-item version [Goldberg and Williams 1988] is a short self-rated scale designed to screen for psychological distress in the community. It is probably the most widely used and validated self-rated instrument for detection of psychological morbidity. It takes only a few minutes to administer.

The Zarit Burden Interview [Zarit et al. 1980] is a 22-item self-report inventory of direct stress to carers in caring; it was designed for carers of people with dementia and has demonstrated sensitivity to change. Being disease specific gives it primacy in the area.

The Clinical Dementia Rating scale [Morriss, 1993] allows more reliable staging of dementia than MMSE, and is based on caregiver accounts of problems in daily functional and cognitive tasks. It takes only a few minutes for clinicians already familiar with individual cases, and classifies people with dementia into questionable, mild, moderate and severe.

The Global Deterioration Scale [Reisberg et al. 1982] is essentially for staging dementia and takes only 2 min once relevant clinical information has been collated. It has been well validated and classifies cases into seven stages from no complaints through to very severe. Like CDR, it is mainly used to assort cases by severity in research or in service development, as in an individual case, more subtle changes which are important may not be picked up.

The Clinicians Global Impression of Change (CIBIC-Plus) [Schneider et al. 1997] is a comprehensive global measure of detectable change in cognition, function and behaviour, usually requiring separate interviews with patients and carers. It is therefore conceptually attractive for assessing progression, but requires a trained clinician and 10–40 min of interview time so may be unsuited to routine clinical practice.

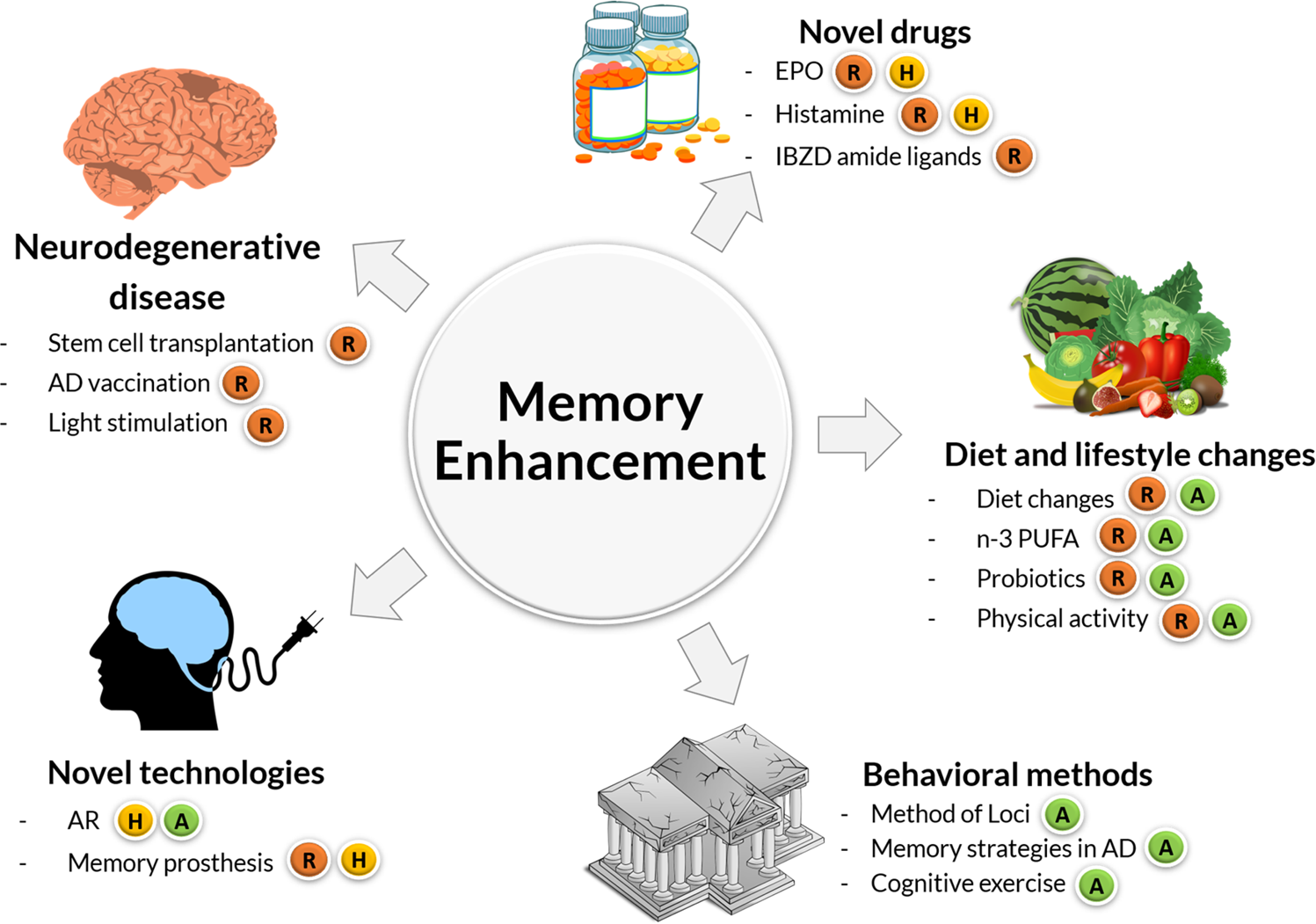

A key consideration in deciding what dementia assessment scales to choose is to clarify the question being asked. Consensus guidelines have been attempted [Ramirez Diaz et al. 2005; Moniz-Cook et al. 2008]. Most of the brief screening instruments like 6-CIT, clock drawing and AMTS are probably psychometrically as good as a common instrument like MMSE in screening for significant cognitive impairment, and are a little shorter. They lack the breadth of assessments in MMSE and are therefore to be used only in settings in which time or frailty make longer assessment impossible. The diagnosis of dementia is always based on a clear history and invariably involves collateral history from an informant along with direct patient assessment. Some comprehensive instruments to aid this diagnosis have been developed. In memory clinics, structured neuropsychological assessment and the use of IQCODE to detail cognitive change as observed by a carer are often used to improve precision of diagnostic decisions. In borderline or mild cases of dementia, assessments probably need to include assessments of at least this complexity, with important guidelines explicitly recommending this [NICE, 2006]. Such assessments will usually involve assessment of premorbid ability and quantification of explicit cognitive deficits, including, but not limited to, memory, and establishing deficits compared with expected norms. Commonly, these specialist assessments involve a specially trained neuropsychologist. Scales like the ACE-R can easily be used in clinical settings by clinicians other than neuropsychologists. In monitoring progress over time, cognition (for example with MMSE, though subject to ceiling/floor effects and relatively insensitive to change), function (e.g. BADLS) or a generic measure of overall severity of dementia(e.g. Clinical Dementia Rating, Global Deterioration Scale, CIBIC) are often used. If cognitive performance is of specific interest, a well validated scale like ADAS-Cog is preferred, despite its length. For clinical trials in which cognition is of primary interest, a de facto gold standard of a four-point change on ADAS-Cog has been established [Rockwood et al. 2007]. In assessing depression in dementia (Cornell scale) and carer stress (Zarit Burden Inventory) there are relatively clear leading assessment scales. Quality of life assessment in dementia is a minefield due to the disparity between patient and proxy ratings, and poor completion rates with more severe dementia. The recent introduction of dementia-specific scales for quality of life, which allow proxy ratings, is at least a significant step forward. Assessing change in behavioural symptoms in dementia is especially important in judging treatment effects (for example – has the patient improved during short-term treatment with antipsychotic medication enough to justify risks of continued prescribing?). Well established scales are available for this purpose. A general principle in dementia assessment is that disease-specific instruments are usually markedly superior in clarifying judgements made. Subject to limitations on clinical and research resources, these instruments should be considered first to maximize clinical practice. A great deal of effort goes into choosing and justifying primary outcome measures in research trials; as clarity about intervention effects is so important, basic familiarity with the strengths and weaknesses of commonly used assessment scales in dementia can help improve the rigour of clinical practice.

Appels B., Scherder E. (2010) The diagnostic accuracy of dementia-screening instruments with an administration time of 10 to 45 minutes for use in secondary care: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimer Dis Other Dement

Borson S., Scanlan J., Brush M., Vitaliano P., Dokmak A. (2000) The Mini-Cog: a cognitive vital signs measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

Brodaty H., Moore C. (1997) The Clock Drawing Test for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: a comparison of three scoring methods in a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

Brodaty H., Pond D., Kemp N., Luscombe G., Harding L., Berman K., et al. (2002) The GPCOG: a new screening test for dementia designed for general practice. J Am Geriatr Soc

Brown J., Pengas G., Dawson K., Brown L.A., Chatworthy P. (2009) Self administered cognitive screening test (TYM) for detection of Alzheimer’s disease; cross sectional study. BMJ

Buschke H., Kuslansky G., Katz M., Stewart W.F., Sliwinski M.J., Eckholdt H.M., et al. (1999) Screening for dementia with the Memory impairment Screen. Neurology

Folstein M., Folstein S., McHugh P. (1975) ‘Mini-Mental State’: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res

Hoe J., Katona C., Roch B., Livingstone G. (2005) Use of the QOL-AD for measuring quality of life in people with severe dementia- the LASER-AD study. Age Ageing

Jorm A. (1994) A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med

Jorm A., Jacomb P. (1989) An informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability validity and some norms. Psychol Med

Milne A., Culverwell A., Guss R., Tuppen J., Whelton R. (2008) Screening for dementia in primary care:a review of the use, efficacy and quality of measures. Int Psychogeriatr

Mioshi E., Dawson K., Mitchell J., Arnold R., Hodges J.R. (2006) The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

Moniz-Cook E., Verooij-Dassen M., Woods R., et al. (2008) A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health

Nasreddine Z., Phillips N., Bédirian V., Charbonneau S., Whitehead V., Collin I., et al. (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc

NICE (2006) Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. Clinical guideline 42. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

Ramirez Diaz S., Gregorio P., Ribera Casado J., Reynish E., Ousset P.J., Vellas B., et al. (2005) The need for a consensus in the use of assessment tools for Alzheimer’s disease: the Feasibility study (assessment tools for dementia in Alzheimer Centres across Europe), a European Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium’s (EADC) survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry

Roth M., Tym E., Mountjoy C., Huppert F.A., Hendrie H., Verma S., et al. (1986) CAMDEX. A standardized instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly with special reference to the early detection of dementia. Br J Psychiatry

Smith S., Lamping D., Banerjee S., et al. (2007) Development of a new measure of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: DEMQOL. Psychol Med

Ware J., Kosinski M., Keller S. (1996) A 12 Item Short Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care

The Digital Exam Enables Providers, For The First Time Ever, To Quickly Screen Brain Health During A Typical 40-Minute Wellness Appointment, More Efficiently And Accurately Signaling Early Signs Of Cognitive Decline

(PRESS RELEASE) Neurotrack, the leader in science-backed cognitive health solutions, announced today the launch of the first ever three-minute digital cognitive assessment that enables providers to quickly screen for cognitive decline and impairment which can be an early indicator of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s during their annual wellness exam. This solution could increase the number of annual cognitive assessments completed and provide additional opportunities for early intervention.

In a sample survey of adults with either Medicare Advantage (MA) or fee-for service Medicare, only about a quarter of those enrolled say they received an evaluation (link to citation), despite CMS guidelines that require cognitive assessments as part of annual wellness visits for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part B.

Neurotrack’s digital exam has been designed to fit easily within a typical primary care annual wellness visit or alternately empower patients to independently assess their cognitive health and share the results with their providers. The easy-to-use assessment can identify patients with cognitive impairment in just three minutes, with better accuracy compared to traditional methods and uses culturally-agnostic symbols and numbers to reduce bias in testing for those with other languages, backgrounds, and cultures. For providers, it offers a scalable way to screen patients for potential cognitive issues, regardless of symptoms.

“Early detection is critical for patients facing a diagnosis like Alzheimer’s or dementia, but unfortunately most patients aren’t screened for cognitive impairment until they show symptoms, which can appear more than 20 years after initial brain changes have occurred,” said Elli Kaplan, founder and CEO of Neurotrack. “We want to empower providers to integrate cognitive testing as a new vital sign in annual physical exams starting at age 65, with the hope that an earlier diagnosis for patients with dementia will lead to more effective interventions.”

There are a number of converging factors driving the need for cognitive screening at scale, including an aging population and a critical shortage of neurologists, neuropsychologists and providers specializing in senior care. With a projected one in 10 older adults expected to develop Alzheimer’s, the U.S. will need to triple the number ofgeriatriciansalone by 2050 in order to care for them.

“The need for this type of diagnostic tool, at this time, cannot be overstated,” said Dr. Jonathan Artz, a neurologist at Renown Health, who is a Core Member of a Statewide Planning Team to develop a Nevada Memory Care Network that would include a cognitive health screening platform. “Neurotrack’s technology would make cognitive assessments as part of the yearly Medicare Wellness Visit more manageable and efficient for primary care providers. The Neurotrack offering is well designed and has the features necessary for integration into the Nevada Memory Care Network.”

Dr. Artz added, “Neurotrack’s solution is grounded in proven methodologies that are scientifically validated and can detect possible cognitive impairment. Using this tool within a clinical workflow opens up the possibility for every senior to be screened in a more timely manner and earlier, when an intervention can be most effective.”

“With a rapidly growing aging population and new factors stemming from COVID and the social isolation many experienced during the pandemic, cognitive decline is a significant concern for people over the age of 65. There’s a critical need for these kinds of assessments,” said Dr. Andrew Cunningham, a practicing physician who also serves as a clinical services director for Neurotrack. “This screening tool was designed by primary care physicians for primary care physicians to meet this need and empower providers to better care for their patients.”

Neurotrack is currently developing a new “digital therapeutic” to delay or prevent cognitive decline when early signs are detected. As part of this work, the company is conducting a clinical study in collaboration with researchers at the University of Arkansas to look at the effects of health education and health coaching on cognition and cognitive risk factors, using grant funds from the National Institute on Aging. Preliminary results show significant reduction in symptoms after one year of intervention: thinking and memory improve, and depression and anxiety lessen.

Neurotrack recently secured $10 million in new funding to support and accelerate its successful go-to-market push with leading health systems and providers across the country and to continue the development of a provider-based solution for those identified with cognitive decline. The latest funding is supported by experts in a range of disciplines including technology, clinical care, biotech, patient advocacy and caregiving.

While continuing to expand their clinical interventions and scientific excellence, Neurotrack has engaged physician leaders from family medicine, geriatrics and geriatric psychiatry to form a new clinical advisory board. The board will advise Neurotrack in order to better meet the needs of patients as well as physicians and health systems caring for our aging population.

Neurotrack is a digital health company on a mission to transform the diagnosis and prevention of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The company develops clinically validated digital cognitive assessments, using eye-tracking technology, to measure and monitor the state of one’s cognition. The company has also developed a comprehensive cognitive health program that enables individuals to make lifestyle changes to strengthen their cognitive health as they age. Neurotrack has published 22 peer-reviewed papers and its solutions have been recognized by leading organizations including the Cleveland Clinic and the National Institute on Aging. Working with providers, health systems and employer partners, Neurotrack has enabled more than 150,000 cognitive assessments on its platform. The company is based in Redwood City, CA. For more information visit www.neurotrack.com and/or follow Neurotrack on LinkedIn and on Twitter.

Screening instruments evaluated in more than 1 study included the MMSE, CDT, MIS/MIS-T, MSQ, Mini-Cog verbal fluency, AD8, FAQ, 7MS, AMT, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale, MoCA, SLUMS, TICS, and IQCODE. The MMSE was the most evaluated instrument (30 studies). The MMSE is an 11-item instrument with a maximum score of 30 points. In a pooled analysis of 14 studies using cutoffs of 23 or less or 24 or less (score considered a positive screening result) (n = 11,972), the MMSE had a sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.85 to 0.92) and a specificity of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.86 to 0.93) to detect dementia. The other instruments were studied in fewer studies (2 to 9 studies), and cutoffs for screening instruments often varied across studies. Sensitivity and specificity of these instruments to detect dementia varied widely in these studies, from 0.43 to 1.0 and 0.54 to 1.0, respectively. Across all instruments, test accuracy (ie, sensitivity and specificity) was generally higher to detect dementia compared with MCI.[[16.17]]

Fifty-eight trials (n = 9139) evaluated psychoeducation interventions targeting the caregiver or caregiver-patient dyad. Most trials targeted patients with dementia, and the average MMSE score in studies that reported it was 16.2, consistent with moderate dementia. The interventions were highly variable, with most including training in problem solving, communications, and stress management, in addition to providing information about dementia and community resources. Overall, there was a small improvement in caregiver burden and depression measures, primarily in persons caring for patients with moderate dementia. For example, a pooled analysis of 9 trials (n = 1089) that reported change in the Zarit-22 (a 22-item scale of caregiver burden, with a score ranging from 0 to 88) found an average 2.5-point improvement (mean difference, –2.5 [95% CI, –3.9 to –1.0]), and a pooled analysis of 20 trials (n = 2603) that reported change in the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) (a 20-item scale of depressive symptoms, with a score ranging from 0 to 60) found a mean 2.67-point improvement (mean difference, –2.67 [95% CI, –3.45 to –1.48]) in the intervention groups.[[16.17]]

Seventeen trials (n = 3039) evaluated care or case management interventions. All interventions were intended for patients with dementia. Of the 12 trials that reported caregiver burden outcomes, 5 found a statistically significant improvement in scores. A pooled analysis of 8 trials (n = 1215) found a standardized pooled effect of –0.54 (95% CI, –0.85 to –0.22), translating to a between-group difference of approximately 3.5 to 4 points on the Zarit-22. Seven trials reported caregiver depression outcomes. A pooled analysis of 4 of these trials (n = 668) showed no improvement in caregiver depression measures.[[16.17]]

Overall, the body of evidence on the potential benefits of screening for cognitive impairment is limited by several factors. These include the short duration of most trials (often ≤6 months for pharmacologic agents and ≤1 year for nonpharmacologic interventions), as well as the heterogeneous nature of interventions and inconsistency in the outcomes reported, which make cross-study comparisons difficult. As noted, for interventions for which studies reported an improvement in measures, the average effect sizes were small and of uncertain clinical importance. In addition, no interventions specifically targeted a screen-detected population. Most of the evidence suggesting improvement is applicable to persons with moderate dementia; thus, its applicability to a screen-detected population is uncertain.

Forty-eight randomized clinical trials (n = 22,431) and 3 observational studies (n = 190,076) reported on the harms of treatment with AChEIs and memantine.[[16.17]] Adverse effects of medications were common. Adverse events were significantly higher in patients receiving AChEIs, and more patients receiving AChEIs withdrew from studies or discontinued their medication compared with patients receiving placebo. Memantine was better tolerated, with no increase in adverse events or withdrawal rates compared with placebo. Overall, there was no increase in serious adverse events in patients taking AChEIs. However, some individual studies reported increased rates of serious adverse events, such as bradycardia, syncope, falls, and need for pacemaker placement among patients taking AChEIs.

Twenty-one of the trials (n = 5688) that evaluated other medications or supplements reported on harms. Harms were not clearly significantly increased in intervention groups compared with control groups.[[16.17]] For nonpharmacologic patient-level interventions, few studies reported on harms. Little harm was evident in the 12 studies (n = 2370) that reported it.[[16.17]]

A draft version of this recommendation statement was posted for public comment on the USPSTF website from September 10, 2019, to October 7, 2019. Several comments agreed that the evidence on screening for cognitive impairment is insufficient. Several comments expressed that readers might misinterpret the I statement as a recommendation against screening, or interpreted the I statement as a recommendation against screening. In response, the USPSTF wants to clarify that its I statement is a conclusion that the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment and is neither a recommendation for nor against screening. Several comments disagreed with the I statement and felt that the USPSTF should recommend screening for cognitive impairment based on the potential benefits mentioned in the Practice Considerations section. In response, the USPSTF clarified that while there may be important reasons to identify cognitive impairment early, none of the potential benefits mentioned in this section have been clearly demonstrated in controlled trials. Several comments noted that cognitive impairment often goes unrecognized. The USPSTF agrees and added language to the Practice Considerations section noting that clinicians should remain alert to early signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment. Some comments suggested additional studies that should be considered by the USPSTF. Some of the suggested studies investigated the prevention of cognitive impairment by controlling risk factors, such as hypertension, or by use of a multidomain intervention (eg, diet, physical activity, cognitive training, and risk factor control). However, none of these suggested studies met inclusion criteria for this recommendation; that is, they were not studies of screening for and/or treatment of cognitive impairment or mild to moderate dementia. Also, the USPSTF added the American Academy of Neurology’s guidelines on the detection of cognitive impairment to the Recommendations of Others section.

Dementia can be the result of varied and different pathophysiologic processes affecting the brain, and the exact causal mechanism for many types of dementia is unknown. Therefore, the development of early interventions that result in important clinical effects on dementia has been challenging. The most common cause of dementia in the United States is Alzheimer disease, which is the target of all current drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for dementia. Since current medical therapies for dementia do not appear to affect its long-term course, the potential benefit of screening may be in devising effective interventions that can help patients and caregivers prepare for managing the symptoms and consequences of dementia.

Dementia is a global public health problem. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a proprietary instrument for detecting dementia, but many other tests are also available.

Literature searches were performed on the list of dementia screening tests in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsychoINFO from the earliest available dates stated in the individual databases until September 1, 2014. Because Google Scholar searches literature with a combined ranking algorithm on citation counts and keywords in each article, our literature search was extended to Google Scholar with individual test names and dementia screening as a supplementary search.

Studies were eligible if participants were interviewed face to face with respective screening tests, and findings were compared with criterion standard diagnostic criteria for dementia. Bivariate random-effects models were used, and the area under the summary receiver-operating characteristic curve was used to present the overall performance.

Eleven screening tests were identified among 149 studies with more than 49 000 participants. Most studies used the MMSE (n = 102) and included 10 263 patients with dementia. The combined sensitivity and specificity for detection of dementia were 0.81 (95% CI, 0.78-0.84) and 0.89 (95% CI, 0.87-0.91), respectively. Among the other 10 tests, the Mini-Cog test and Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised (ACE-R) had the best diagnostic performances, which were comparable to that of the MMSE (Mini-Cog, 0.91 sensitivity and 0.86 specificity; ACE-R, 0.92 sensitivity and 0.89 specificity). Subgroup analysis revealed that only the Montreal Cognitive Assessment had comparable performance to the MMSE on detection of mild cognitive impairment with 0.89 sensitivity and 0.75 specificity.

Besides the MMSE, there are many other tests with comparable diagnostic performance for detecting dementia. The Mini-Cog test and the ACE-R are the best alternative screening tests for dementia, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment is the best alternative for mild cognitive impairment.

Early diagnosis of dementia can identify people at risk for complications.,3 have found that health care professionals commonly miss the diagnosis of cognitive impairment or dementia; the prevalence of missed diagnosis ranges from 25% to 90%. Primary care physicians may not recognize cognitive impairment-6 Screening tests are quick and useful tools to assess the cognitive condition of patients.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),8 However, there are more than 40 other tests available for dementia screening in health care settings, many of which are freely available, such as Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–Revised (ACE-R),

This systematic review followed standard guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of diagnostic studies, including Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)

A list of screening tests was identified in previous systematic reviews.Alzheimer, Parkinson, vascular, stroke, cognitiveimpairment, and dementia. Diagnostic studies comparing accuracy of screening tests for detection of dementia were manually identified from the title or abstract preview of all search records. The selection was limited to peer-reviewed articles published in English abstracts. Because Google Scholar searches literature with a combined ranking algorithm on citation counts and keywords in each article, our literature search was extended to Google Scholar with individual test names and dementia screening as a supplementary search. The first 10 pages of all search records were scanned. Manual searches were extended to the bibliographies of review articles and included research studies. Screening tests were classified into different categories according to the administration time: 5 minutes or less, 10 minutes or less, and 20 minutes or less.

Cross-sectional studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) involved participants studied for the detection of dementia associated with Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, or Parkinson disease in any clinical or community setting; (2) screened patients or caregivers with a face-to-face interview; (3) used standard diagnostic criteria as the criterion standard for defining dementia, including the international diagnostic guidelines (eg, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, International Classification of Diseases, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Association Internationale pour la Recherche et L’Enseignement en Neuroscience criteria, or clinical judgment after a full assessment series); (4) reported the number of participants with dementia and evaluated the accuracy of the screening tests, including sensitivity, specificity, or data that could be used to derive those values. Studies were excluded if they were not written in English or only included a screening test that (1) requires administration time longer than 20 minutes, (2) was identified in fewer than 4 studies in the literature search, or (3) was administered to participants with visual impairment.

Two investigators (J.Y.C.C., H.W.H.) independently assessed the relevancy of search results and abstracted the data into a data extraction form. This form was used to record the demographic details of individual articles, including year of publication, study location, number of participants included, mean age of participants, percentage of male participants, type of dementia, recruitment site, number of participants with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), diagnostic criteria, cutoff values, sensitivity, specificity, and true-positive, false-positive, true-negative, and false-negative likelihood ratios. When a study reported results of sensitivity and specificity across different cutoff values of a screening test, only the results from a recommended cutoff by the authors of the article were selected. If the study did not have this recommendation, the cutoff used to summarize sensitivity and specificity in the abstract was chosen. When discrepancies were found regarding inclusion of studies or data extraction, the third investigator (K.K.F.T.) would make the definitive decision for study eligibility and data extraction.

Statistical analyses were performed with the Metandi and Midas procedures in STATA statistical software, version 11 (StataCorp). The overall sensitivity and specificity of each diagnostic test were pooled using a bivariate random-effects model.I2, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to the heterogeneity rather than the chance alone. P < .10 was considered as statistically significant heterogeneity. Because we used random-effects models to combine the results, the heterogeneity among the studies was taken into account.

Subgroup analysis was conducted across the studies by geographic regions, recruitment settings, and patients with MCI. Geographic regions were classified as Americas, Asia, and Europe. Recruitment could be performed in the community, memory clinics, cognitive function clinics, or hospitals. The definitions of participants with MCI were according to the cutoff values suggested in the individual studies.

A total of 26 165 abstracts were identified from the databases, and 215 potential studies were further extracted from the bibliographies. All titles or abstracts were screened, and 346 articles were relevant to screening tools for dementia. One hundred ninety-seven were excluded for the following reasons: studies were systematic reviews (n = 30), studies did not fulfill inclusion criteria (n = 121), studies lacked data details for meta-analysis (n = 39), and studies reported results of screening tests without comparing to a criterion standard (n = 7) (Figure 1). The definitive analysis in this systematic review included 149 studies published from 1989 until September 1, 2014, for patients with dementia from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and 30 other countries.

A total of 11 screening testsSupplement) for the MMSE,Table 1. High scores represented good cognitive function in most screening tests, except the IQCODE.

A total of 149 studies with more than 40 000 patients across the 11 screening tests were included (Table 2). One hundred ten eligible studies (73.8%) reported the diagnostic performances of at least 2 screening tests, including those compared with the MMSE. Approximately 12 000 participants were confirmed as having dementia (Table 2). Most studies (68.5%) used the MMSE as the screening test for dementia in 29 regions. The next most common screening test studied was the MoCA, which was used in 20 studies (13.4%) from 9 countries. Patients were mainly recruited from community or clinic settings (80.3%). One hundred ten (73.8%) of 149 studies had good study quality with quality scores of 7 to 8. The quality scores were comparable across the 11 screening tests with median scores of approximately 7 (range, 3-8). The original data of each study on the true-positive, false-positive, false-negative, and true-negative likelihood ratios were presented (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Furthermore, risks of bias were not identified among these studies, and only the studies for the GPCOG, MoCA and modified MMSE revealed approximately 20% to 30% high risks of bias on execution for the index test and the reference standard (Table 2).

There were 10 263 cases of dementia identified from 36 080 participants in 108 cohorts studying the MMSE. The most common cutoff values to define participants with dementia were 23 and 24, used in 48 cohorts (44.4%). With different cutoff threshold values, we found considerable variation in the sensitivity and specificity estimates reported by individual studies. The sensitivities ranged from 0.25 to 1.00, and the specificities ranged from 0.54 to 1.00. The heterogeneity among studies was large, with I2 statistics for sensitivity and specificity of 92% and 94%, respectively. The diagnostic accuracy is summarized by meta-analysis (Table 3). The combined data in the bivariate random-effects model gave a summary point with 0.81 sensitivity (95% CI, 0.78-0.84) and 0.89 specificity (95% CI, 0.87-0.91). The HSROC curve was plotted with a diagnostic odds ratio of 35.4, and the AUC was 92% (95% CI, 90%-94%) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

The performances of the other 10 screening tests were summarized by random-effects models (Table 3). All tests presented with AUCs of at least 85%, and most of the tests had comparable performance to that of the MMSE. The Mini-Cog test and the ACE-R were the best alternative tests. Among the studies with the Mini-Cog test,Figure 2A). The heterogeneity among studies was large, with I2 statistics for sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 97%, respectively. Among studies that used the ACE-R,Figure 2B). The confidence regions of the HSROC curves for sensitivity and specificity of the Mini-Cog test and the ACE-R were plotted with reference to the HSROC curve of the MMSE (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Only the MMSE had a sufficient number of studies to perform subgroup analysis. For the geographic regions, studies were conducted in Europe (44.4%), Americas (31.5%), and Asia (23.1%). The diagnostic performances of the MMSE were comparable across these regions with similar AUCs (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). For the recruitment settings, participants were recruited in hospital (9.3%), clinic (32.4%), primary care (12.0%), community (38.9%), and other settings (7.4%). The diagnostic performances were comparable across different recruitments settings (P > .05 for all) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Only 21 of 108 cohorts reported diagnostic performance of the MMSE for the detection of MCI. The combined data gave a summary point of 0.62 sensitivity (95% CI, 0.52-0.71) and 0.87 specificity (95% CI, 0.80-0.92). Nine of 20 studies reported diagnostic performance of the MoCA for the detection of MCI.Figure 2C). The confidence regions of the HSROC curve for sensitivity and specificity of the MoCA were plotted with reference to the HSROC curve of the MMSE (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 149 studies that assessed the accuracy of the MMSE and 10 other screening tests for the detection of dementia. Compared with other screening tests, the Mini-Cog test and the ACE-R had better diagnostic performance for dementia, and the MoCA had better diagnostic performance for MCI. The Mini-Cog test is relatively simple and short compared with the MMSE.

Diagnostic sensitivity improves with lower cutoff values but with a corresponding decrease in specificity. High sensitivity corresponds to high negative predictive value and is the ideal to rule out dementia. We found considerable variation on the definitions of cutoff thresholds among the individual studies. According to our selection criteria, the most common cutoff scores for the MMSE for dementia were 23 and 24 (44.4% study cohorts), and approximately 20% of eligible cohorts used cutoff scores of 25 to 26 (range, 17-28). The range of scores for the Mini-Cog test is similarly 0 to 5, and 7 cohorts (77.8%) used a score of less than 3 as the cutoff for dementia, indicating disagreement on the optimal cutoff score across different screening tests. The users of screening tests should strike a balance between sensitivity and specificity to rule in or out the participants with dementia according to the available resources.

This study has several limitations. First, the screening tests were not directly compared in the same populations. Each study used different populations, and the inclusion criteria and prevalence of dementia varied. It would be preferable to directly compare screening tests using the same group of participants with similar educational levels. Second, only a few studies were included that showed head-to-head comparison between the screening tests, so the test performance could not be directly compared. Third, the screening tests were translated into different languages, which may have unknown effects on the results. We assumed that the tests were all validated in various languages in the individual studies although this was not guaranteed, and unidentified cultural effects on the use of screening tests may still exist. Fourth, we only included studies that reported the diagnostic performance of screening tests for dementia. Although we used MCI as a secondary outcome, the definitions of MCI were heterogeneous across studies. Studies that only reported the results of MCI or cognitive impairment but not dementia (cognitive impairment no dementia) were not included in this meta-analysis. Finally, some unpublished studies may not have been identified through the literature search in OVID databases, and publication bias may exist.

This review systematic and meta-analysis found that the MMSE is the most frequently studied test for dementia screening. However, many other screening tests have comparable diagnostic performance. The Mini-Cog test and the ACE-R had better performance than the other dementia screening tests. The MoCA had better performance than the other MCI screening tests. Although the MMSE is a proprietary instrument for dementia screening, the other screening tests are comparably effective but easier to perform and freely available.

Author Contributions: Dr Tsoi had full access to all the data in

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey