difference between viewfinder and lcd screen quotation

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/LCD-vs-Electronic-Viewfinder-a450f05ded58420e869025658fd362a9.jpg)

LCD screens are great, and the quality improves with each new generation of DSLR cameras appearing on the market. But, many professional photographers prefer to use a camera"s viewfinder. We explain the benefits and disadvantages of each.

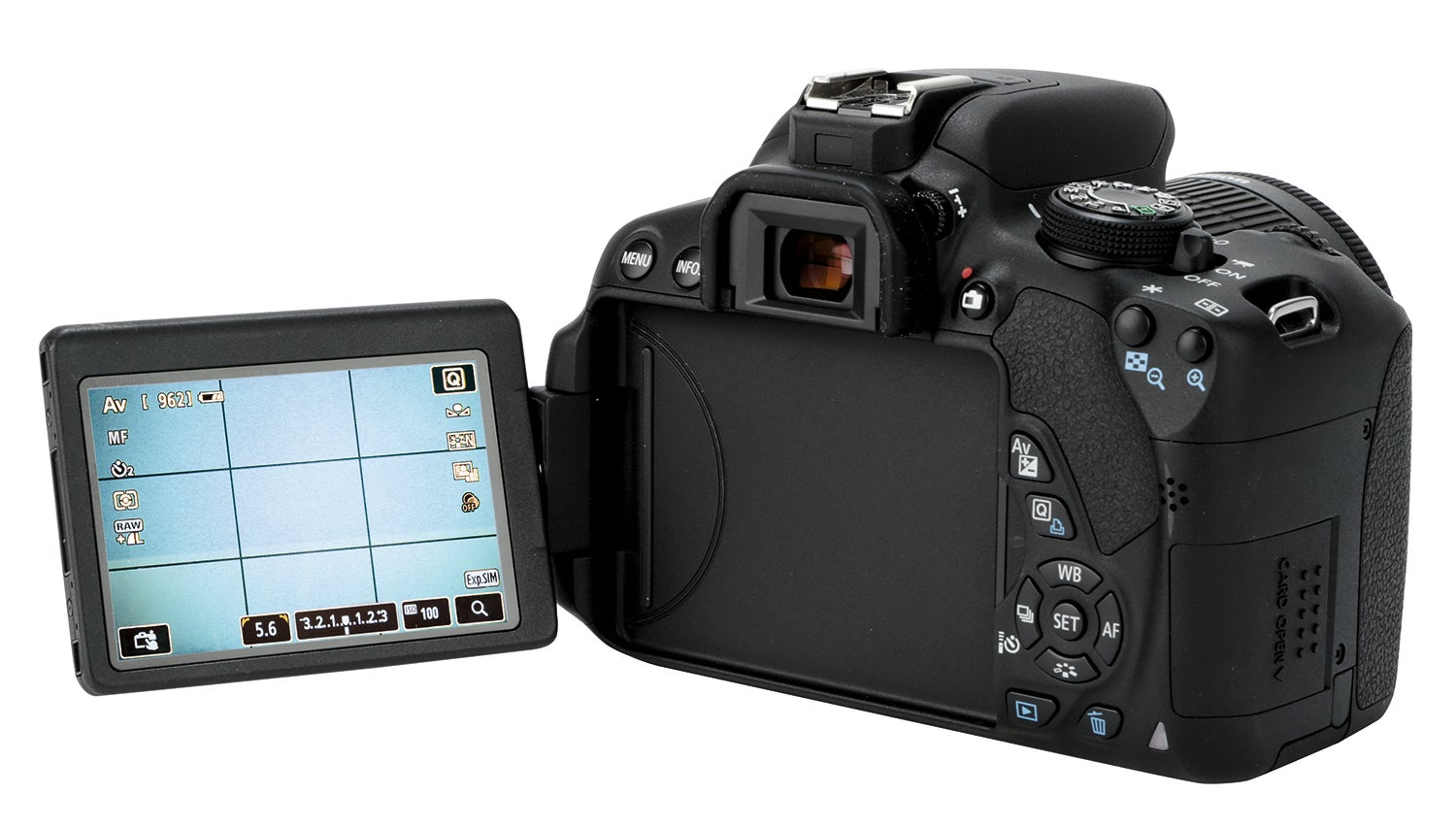

LCD screens have advantages, but so do optical viewfinders. When it"s time to frame a photo with your DSLR camera, you need to decide which side of the viewfinder vs. LCD debate you lean. Unlike the optical viewfinder, the LCD screen displays the entire frame that the sensors capture. Optical viewfinders, even on a professional level DSLR, only show 90-95% of the image. You lose a small percentage on the edges of the image.

Digital SLRs aren"t light, and it"s easier to produce a crisp, sharp image when you hold the camera up to your eye to use the viewfinder. That way, you can support and steady the camera and lens with your hands. But, viewfinders are generally smaller than LCD screens. Viewfinders are also less convenient to use, especially if you wear glasses.

At the end of the day, though, as intelligent as digital cameras are, the human eye can resolve more detail than an LCD screen. You get a sharper and more accurate view of your image by using the viewfinder.

The biggest drawback with LCD screens is probably shooting in sunlight. Depending on the quality of the screen, you may not be able to use it in bright sunshine because of the glare. All you see are reflections off the screen. Also, the crystals contained within LCD screens tend to flare in bright sunlight, making the situation worse.

Holding the camera at arm"s-length while looking at the LCD screen—and then keeping the camera steady while zooming in on a subject—takes effort. When you use the LCD screen this way, you often end up with a blurry image.

No matter how good an LCD screen is, it"s unlikely to give an accurate overview of the image you took. Most overexpose an image by as much as one full stop. It"s best to acquire the technical knowledge about photography, rather than rely on the LCD screen to determine image quality. With this technical knowledge, you"ll have the confidence your settings are correct, and your images are properly exposed. So, in most cases, it"s best to use the viewfinder. But, if you like the convenience of an LCD, or you wear glasses, use the LCD. It"s mostly a matter of personal preference.

The benefits of the viewfinder and LCD screen are often compared with one another. Depending on whom you ask, you might hear remarkably different opinions on the usability of the two.

Let’s go through some of the pros and cons of both and present you with an objective case for why you should pick one over the other. Keep in mind that this isn’t meant to dictate which shooting method you should use. There are valid reasons to use both; it just depends on the situation.

As discussed above, photography is all about precision. Viewfinders have been around long before LCD screens, and therefore many photographers find viewfinders more comfortable to work with.

Viewfinders offer much more precision when you are shooting, especially on a bright day. It allows you to focus on the small details. Viewfinders reduce image distortion and capture an accurate image. That’s why most DSLRs and high-end mirrorless cameras today still have viewfinders.

Running out of battery is a nightmare for photographers, especially if you don’t have any spares. That’s why viewfinders are considered optimal in these situations. Viewfinders use comparatively much less battery than LCD screens.

If you are shooting in an area where electricity is scarce, or don’t have access to a charger or backup batteries, the viewfinder will be a better choice for you.

Viewfinders are very convenient to use and provide smooth handling. When looking through the viewfinder, it’s easy to keep the camera steady. This makes the viewfinder an optimal choice when you need to zoom in or have a slightly heavier camera.

For many people, this extra effort of adjusting your eyeglasses is troublesome. However, some viewfinder cameras have a built-in diopter that can help make it easier to use with glasses.

Viewfinders can be much smaller compared to LCD screens. As a result, you may not be able to see everything you’re capturing in the viewfinder accurately. This drawback is very important for photographers who want to preview every single detail when taking a picture.

To see details on viewfinders, especially the electronic ones, you have to zoom in on the frame. However, this can lower the resolution of the preview. Luckily, if most of your shots consist of zoom shots, this may not bother you much.

What sets LCD screens apart from viewfinders is their ability to provide 100% image coverage to the photographer. In comparison, cameras with a viewfinder offer around 90-95% of the image, sometimes less.

What you see through the viewfinder doesn’t always end up in the final result. Small details can be crucial. That’s why this 5-10% difference in image coverage can be a significant reason why you might choose an LCD screen over the viewfinder.

When you are in a lower field-of-view, framing can be much more difficult. Many people can’t take a picture while lying on the ground using a viewfinder. This is where LCD screens come in. Flexible LCDs make it easier for you to capture images when you can’t reach awkward angles.

LCD screens produce great results for night photography. LCD screens are often used for night photography due to their bright image playback quality. They help you focus on the small details when you are shooting at night.

An evident shortcoming of the LCD screen is its lack of utility on a bright day. Because of the glare, many people cannot use their LCD screen at all on a sunny day. It’s hard to see anything on the LCD except the reflections.

Another drawback to using an LCD screen is its difficulty in handling it. Holding the camera while looking through the LCD screen is difficult and takes a lot of effort, especially when you are zooming and trying to be precise.

Another disadvantage of LCD screens is the fact that they can easily overexpose your image. This should not be a problem for seasoned photographers who can improve the quality of the image with better handling and precision.

Those were some of the benefits and drawbacks of using a viewfinder and LCD screen to consider. So, which one is best? The answer depends on your personal preferences and budget.

If you’re a traditional photographer, you’ll probably be more comfortable with the viewfinder. If you are a photographer who likes to focus on small details and image quality, you should opt for the LCD screen.

Whether you"re shooting with a DSLR or a mirrorless camera, there are times when it"s easier to use the camera"s viewfinder rather than the LCD screen, and vice versa. For example, it"s usually easier to hold the camera steady when it"s held to your eye because it"s braced against your face. It"s also easier to follow a moving subject in a viewfinder than it is on a screen with the camera at arm"s length.

However, when you"re shooting landscape, still life, macro or architectural photography with the camera mounted on a tripod, the larger view provided by the LCD screen is extremely helpful. Similarly, when you want to shoot from above or below head height or at an angle, it"s very convenient to frame the image on a tilting or vari-angle screen instead of trying to use the viewfinder.

It"s also very helpful to use the LCD screen when you"re focusing manually because the Live View image can be zoomed in to 5x or 10x magnification. This provides a very detailed view of any part of the image, making critical focus adjustments much easier.

On the EOS 90D in Live View mode and on mirrorless cameras including the EOS R5, EOS R6, EOS R, EOS RP, EOS M6 Mark II and EOS M50 Mark II, you can also enable Manual Focus Peaking (MF Peaking), a visual aid to show which parts of the image are in sharpest focus. In theory, areas in focus will coincide with the greatest contrast, so the image is evaluated for contrast and these areas are highlighted on the display in a bright colour of your choice. You can see the highlighted areas of the scene change as you change the focus.

Bear in mind, however, that using your camera"s rear screen for extended periods will have an impact on battery life. Using Live View on a DSLR is also not recommended when you want to take fast bursts of shots, because it will usually reduce the continuous shooting speed. At the other extreme, if you"re shooting an exposure that lasts for multiple seconds or minutes, an optical viewfinder can cause a particular problem: stray light can enter the viewfinder and interfere with the exposure. To prevent this, use the eyepiece cover provided on your DSLR"s strap.

EOS cameras with an EVF have a proximity sensor that will automatically switch from the rear screen to the viewfinder when you raise the camera to your eye (although you can optionally disable this).

use the viewfinder may become impossible when the view gets worse as with presbyopia. in spite of the trouble that sunlight has on lcd, I can not use the viewfinder, for a variety of reasons that complicate and prevent it from being ready to take the photo,

- If I keep them in my hand, I can not use the camera and use all the control functions with only one hand, perhaps with a small compact that will always fire in automatic, but not with a mirrorlees.

If you still find a way to support his glasses, you have another problem, when you take glasses and look in the viewfinder, you have visual mismatch for a few seconds, then return the glasses, yet the visual mismatch, if you do studio photography, perhaps ok not a problem, but if you"re on the road, you have to seize the moment ..

In order to achieve good photos, ok important the feeling with their own camera, and with the world around you, the act of making a photograph has to be spontaneous, and more complicated, the less you are able to do photography, if it is too complicated passes the desire to do photography.

I use lcd from many advantages for action photo, I see both the image and all the controls of the camera, I am always ready to make photo adjustments a snap.

if I need to move area of focus, with lcd touch and very easy, I can take the photo, when in doubt click again with different setting, with memory card we have many great variation with, with the film was the most expensive ..

I am talking after the photo is taken. I for the first time pressed the playback button and put my eye onthe viewfinder to see the image from there, and it looked exactly as ehat i was seeing before capturing it, but when i look at the image thru the screen the shadows are a lot darker, the contrast higher etc, in less words different.

i like what i have capturend when i see them through the viewfinder but my raws on the screen look very confusing.( also i know i can edit them later but was wondering what is it that makes it like this.

That is my experience too. And for JPEGs, the LCD matches what other media would show, especially the dark areas. I would not say the viewfinder lacks contrast, but you are right in that the details in the shadows (dark areas) are deceptively clear in the viewfinder. And there is no setting to change that: the lowest brightness of the viewfinder also shows the same amount of shadow details.

This is both good and bad: Good: Even if the shadows are going to be very dark, they will be visible in the viewfinder while composing (and while reviewing), and since the details are there, you can be assured that you recover them later if you are shooting raw. Bad: If you shoot JPEG, and rely on viewfinder for verifying the shadow details, then you will be disappointed later.

Regarding "my raws on the screen look very confusing": it does not matter if you are shooting raw or jpeg; the images shown in the viewfinder or the LCD do not change depending on raw/jpeg. (They do change with picture control though.)

Hope you caught the first line of my last post as a joke, and that you recognize that most of my ire about camera design is reserved for whomever else might have the power to change it.

Melissa, there will come a time in your growth into photography that you may begin to recognize that some of the most important stuff happens before you look through the viewfinder. The viewfinder will come to be mostly a confirmation of what you expect from your picture. It"s more of a final, but important, check.

There have been many good photos made with little more than a peephole and a wire frame for viewfinding. I have, and still use, one such camera. It can take a little more time, but once you get there, you may not notice. You"ll probably be too busy composing and visualizing before you make the picture.

The newer versions. Well, you can see I"m not a big fan. Yet, not only should the structure of the viewfinder not be too influential; there will come that time when non-reflex work, pictures without a look through the lens, will be important. The oldest of cameras were like this. We"ve just seen a computerized simulation of the return to these practices, except the contemporary kind is hybridized into that LCD interface in the point and shoot.

Back when, George Eastman needed plenty of ladies to gather chicken eggs and cook "em up in order to build his empire. In his first camera, I think there was no viewfinder at all. I think it was in the second camera that they added a mirrored window to help people aim the camera. Its screen was small enough to fit on the face of a dime.

The thinking before you use the viewfinder will come to be more important as you start to round out your basic skills as a photographer. You might find that this thinking may be one of the most influential segments of your creative process, later. The more I make pictures, the more before the camera work occupies me quite a bit.

The viewfinder is your window to the world as a photographer – despite advancements in camera technology, the humble viewfinder remains relatively unchanged.

An electronic viewfinder is a small display that shows the scene you have in front of the camera. With an electronic viewfinder (EVF), you can see exactly what your sensor sees.

This means that you have a live version of the image you’re about to shoot. If you change the settings, the exposure changes on the viewfinder before you take the picture.

With some cameras, you can connect an external camera screen (see our guide) which mimics the EVF’s display, allowing you to see fine details and colours even clearer.

With optical viewfinders, the image may be different from the view because you’re not seeing the effect of the settings. In other words, if you change camera settings like aperture or shutter speed, it won’t be reflected in the viewfinder.

They display the settings information and focus points though, so you don’t have to take your eye off the viewfinder while focusing and taking your shot.

When the light comes in through the lens, it hits a mirror that sits in front of the sensor. Thanks to the angle of the mirror, the light bounces up towards a pentaprism. Here it’s directed towards the eyepiece to show the scene in front of the lens. Electronic viewfinder

When the light comes in, the sensor registers and processes the scene, which then sends it to the electronic viewfinder’s small display. Because it’s an electronic representation, you can see the exposure settings live.

It depends on the type of photography that you do, but the general answer would be yes. We’re getting used to taking a picture using only an LCD screen because of our smartphone cameras. However, in most situations, a viewfinder will help you improve your framing and composition.

Most DSLR cameras have an optical viewfinder. That means that you see the same thing as your lens, which means that it’s not affected by the exposure settings.

Photographers look through the viewfinder to get a better view of what they are shooting. For example, when you’re shooting on a bright sunny day, you can’t see many details on the LCD screen.

Normally, photographers use their dominant eye. That’s to say that a right-handed photographer will look through the viewfinder with the right eye, and a left-handed photographer will use the left eye. Of course, you’re welcome to use whichever one you prefer.

Yes, you can buy an external viewfinder for your camera. There are electronic and optical viewfinders on the market, and they can be attached to your camera via the hot shoe.

The main difference between viewfinders and LCD screens is in the way you see the scene that’s in front of you. On the LCD screen, you can see a digital representation of it, like looking at the tv. With an optical viewfinder, you’re seeing things through a piece of glass – it can be compared to looking through a window or a pair of binoculars.

Also, with a viewfinder (both OVF and EVF) you don’t have to deal with glare, you have a steadier hold of the camera, and you get better peripheral vision when you shoot.

The viewfinder helps you to frame and compose in the best possible way. Many photographers can’t live without a viewfinder on their camera, whether it’s electronic or optical.

It depends on the camera brand and model. Most entry-level mirrorless cameras don’t have a viewfinder. However, if you can spend a little bit more, you’ll find mirrorless cameras with built-in electronic viewfinders.

Hopefully, this article cleared up some of your doubts about viewfinders and how they can be used to take the possible image with your camera – whether it be analogue or digital.

I know it’s a lot of information and it can be confusing, so if you have any other questions about viewfinders, feel free to post them in the comments section below.

A critical piece of any camera kit is the tool that allows you to view and monitor your image. This can be as simple as a screen that’s attached to the camera, or something more expensive like an EVF (electronic viewfinder) or an external monitor.

When it comes to viewfinders and external monitors, the options are quite vast. Oftentimes, filmmakers on a tight budget can find themselves having to choose between them. But, how do you know which tool is right for you? Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of both tools, and figure out when you might want to choose one over the other.

Different types of content creators have different shooting styles. Taking a close look at how and what you shoot will help you figure out what specific features you want vs. what features you actually need.

Both viewfinders and external monitors can range widely in price, with viewfinders being generally more expensive. If you plan your budget correctly, you might be able to get both of these tools for a good price.

Once you figure out your most common shooting style and budget, you’ll be able to hone in on what you need. Here are just a few of the features/options to consider when you’re making a decision:

If your shoot requires a lot of handheld work, the viewfinder is a solid choice. They’re especially useful for outdoor run-and-gun style shoots. A viewfinder allows you to view your image unobstructed by your peripheral vision or distracting sunlight. You won’t have to worry about glare from the sun, or if the screen is even bright enough to see on especially sunny days.

Also, when your face is pressed against an eyepiece, it acts as an additional point of contact. This helps to further stabilize your shots while operating without a tripod. Some of the more expensive models can also tilt and telescope easily.

Many viewfinders take power from the camera, which will obviously eat up power faster. Some models are also susceptible to burn-ins, which happens when you leave the viewfinder pointing directly at the sun without a cover.

In general, finding a good viewfinder is a bit more difficult than finding an external monitor. Whether you go with a third-party product or something that’s camera native, expect to shell out a little more for a good one. Finding a cheap option isn’t as simple as with external monitors.

When it comes to monitors, there are a plethora of budget-friendly, universal options. They’ll generally fit on any rig, whereas a viewfinder usually requires extra pieces and parts. If you’re working with a crew, they allow others to easily gather around and check the shot. (This can be both a pro and a con.)

One of the big differences between an external monitor and a viewfinder is that a monitor often doubles as a recorder. If your budget allows, you can connect a wireless setup and go roaming. This is perfect for a Director/DP or a DP/Camera Operator setup. Some models even offer camera controls, such as remotely triggering recording.

The main downside of an external monitor is exactly what makes the viewfinder so attractive. Shooting outside is a big concern, and glare from the sun can easily cause you to miss the shot. And, if it isn’t glare, then you might need to worry about brightness. You can always go with a bigger, brighter monitor, but then you begin to lose your mobility.

You’ll also need to focus on power. Make sure you have the necessary batteries, and enough for the duration of your shoot. These batteries can add extra weight, another downside for you run-and-gun shooters.

Whether you"re shooting with a DSLR or a mirrorless camera, there are times when it"s easier to use the camera"s viewfinder rather than the LCD screen, and vice versa. For example, it"s usually easier to hold the camera steady when it"s held to your eye because it"s braced against your face. It"s also easier to follow a moving subject in a viewfinder than it is on a screen with the camera at arm"s length.

However, when you"re shooting landscape, still life, macro or architectural photography with the camera mounted on a tripod, the larger view provided by the LCD screen is extremely helpful. Similarly, when you want to shoot from above or below head height or at an angle, it"s very convenient to frame the image on a tilting or vari-angle screen instead of trying to use the viewfinder.

It"s also very helpful to use the LCD screen when you"re focusing manually because the Live View image can be zoomed in to 5x or 10x magnification. This provides a very detailed view of any part of the image, making critical focus adjustments much easier.

On the EOS 90D in Live View mode and on mirrorless cameras including the EOS R5, EOS R6, EOS R, EOS RP, EOS M6 Mark II and EOS M50 Mark II, you can also enable Manual Focus Peaking (MF Peaking), a visual aid to show which parts of the image are in sharpest focus. In theory, areas in focus will coincide with the greatest contrast, so the image is evaluated for contrast and these areas are highlighted on the display in a bright colour of your choice. You can see the highlighted areas of the scene change as you change the focus.

Bear in mind, however, that using your camera"s rear screen for extended periods will have an impact on battery life. Using Live View on a DSLR is also not recommended when you want to take fast bursts of shots, because it will usually reduce the continuous shooting speed. At the other extreme, if you"re shooting an exposure that lasts for multiple seconds or minutes, an optical viewfinder can cause a particular problem: stray light can enter the viewfinder and interfere with the exposure. To prevent this, use the eyepiece cover provided on your DSLR"s strap.

EOS cameras with an EVF have a proximity sensor that will automatically switch from the rear screen to the viewfinder when you raise the camera to your eye (although you can optionally disable this).

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Though some DSLR (Digital Single Lens Reflex) cameras have EVFs, a major consideration when selecting between an MILC (Mirrorless Interchangeable Lens Camera) and a conventional DSLR is that the MILC will not have an optical viewfinder (OVF).

As more MILCs become available and advanced, and as this camera type gains in popularity, these questions are becoming more important ones for this site"s audience to answer.

Safe to say is that all high-grade cameras produced today have an LCD that can be used for mirror-up, live view of an image that is about to be captured.

A big advantage of an electronic viewfinder is the WYSIWYG (What You See is What You Get) image preview (including with no viewfinder alignment issues).

Able to be included in the LCD image preview is the actual exposure brightness, optionally including a histogram, focus peaking, and over/underexposure warnings.

The mirror assembly has moving parts and moving parts may eventually require replacement (though the life of a DSLR mirror assembly is usually a very significant number of actuations).

Take the lens off of an electronic first curtain shutter MILC (a common design) and the imaging sensor is right there, easily accessible for cleaning (note that some mirrorless cameras now close the shutter when powered off).

The lack of a mirror forces another primary differentiator between non-OVF vs. OVF cameras, and that is, without a mirror, the imaging sensor must be used for all pre-shot calculations, including auto focus and auto exposure.

While there were initially some disadvantages to the mirrorless design in these regards, primarily related to AF speed, the latest mirrorless cameras focus extremely fast, and technology continues to move forward in this regard.

Another is that, with focusing taking place precisely on the imaging sensor, AFMA (Auto Focus Microadjustment) is rarely needed and lens focus calibration becomes a non-issue.

With the tremendously detailed information the sensor makes available, completely game-changing technologies, including subject, face (even a registered face), eye, and smile detection, can be implemented.

While intelligent optical viewfinders have shown great advances in recent years, complete with transparent LCD overlays, they don"t come close to the capabilities of LCDs in terms of the information that can be shown.

A high-resolution LCD panel with a huge palette of colors available provides designers great flexibility in creating a camera"s graphical user interface and also in the customization capability of that interface.

Though a bigger advantage for true EVF cameras, LCD displays can provide an immediate display of a captured image precisely where the photographer is looking at time the image is captured (such as directly through the viewfinder).

However, I must note that this review interrupts the capture of a subsequent image, and I now turn off the EVF image review feature on the mirrorless cameras I"m using.

While some manufacturers (including Canon and Nikon) contend that image stabilization technology works best in the lens vs. in-camera (and there is validity to this claim), inarguable is that the effects of in-camera

However, in bright daylight, even the best rear LCDs become very difficult to see and I find it especially challenging to compose using the rear LCD under direct sunlight.

In contrast, viewfinders make it easy to critically view the composition under even the brightest conditions, giving them a huge advantage over a rear LCD under bright daylight conditions.

Dioptric adjustments provided by viewfinders resolve this issue, permitting a clear view of what I"m about to photograph and review of what I already photographed if it is an EVF.

A camera"s primary LCD tends to collect fingerprints and other smudges at a rapid pace, and these can interfere with visibility of the display, especially in bright light.

However, a viewfinder, with its inset glass, is harder to clean than a primary LCD that, especially if properly coated, easily wipes clean with a microfiber cloth.

A downside is that LCD loupes are not nearly as well integrated into the camera design as EVFs are and built-in EVFs are considerably more compact and less intrusive.

With resolution not limited by dots of pixels (that can appear to flicker as they change colors when framing is adjusted with lower-end EVFs) and refresh rates not limited by an electronic display, advantages of an OVF include higher resolution and speed-of-light responsiveness.

Though the dynamic range of the image captured via an OVF system will similarly be limited by the imaging sensor (and seeing the final result may be advantageous), seeing the full brightness range of the scene is different.

While an LCD can make low light composition easier, a photographer"s eye must constantly adjust between the bright display and dark ambient light levels.

While not directly related to the viewfinder type, MILCs are very commonly given EVFs with reduced camera size and weight being two of the common design targets.

Especially with the smaller MILCs, using large lenses and full-sized flashes can lead to a tail-wagging-the-dog scenario where the provided grip is inadequate or only marginally adequate to maintain control of the overall setup.

While on the size topic, if considering an MILC for size and weight reduction purposes, make sure that the MILC lenses you need do not make up for some of the camera footprint and weight difference.

While most of these cameras indeed have a smaller footprint than their DSLR equivalents, the size of the lenses needs to be considered, and these are not necessarily smaller.

Though mirrorless cameras often utilize a short back-focus lens design and some lenses are indeed smaller, some of the smaller lenses also have narrower maximum apertures.

And, it makes the camera (or each lens) effectively larger and heavier in use, with, for example, the EF to EOS-M adaptor adding a modest 1" (26mm) and 3.77 oz. (107g) respectively.

With the imaging sensor required to be powered up for an EVF to function and because an EVF"s full-color LCD requires its own share of power, EVFs require more battery capacity for an equivalent number of photos to be captured.

Additional batteries add to the system cost, carrying extra batteries adds to the system weight, and maintaining the charge of additional batteries requires maintenance and logistics – and probably at least a second charger, as you can potentially drain batteries faster than you can charge them.

Initially, most OVF systems had a significantly shorter viewfinder blackout time during the image capture, and if following action, this is a critical factor.

The difference was significant enough that one may find EVF cameras practically unusable for tracking/framing a moving subject even with image review turned off.

Digital cameras work very much like film cameras. The quality of the image depends on the quality of the lens and the sensor chips in the camera (which convert the light into a digital signal).

Some higher-end models are just camera back and accept interchangeable lenses. Others have the capability to use screw mount lenses used on video cameras. These options allow for close-up portraits and wide-angle shots. Close-up lenses are also available for some models.

Most cameras come with a built-in flash. The higher-end models have a hot shoe for an attachable flash unit, allowing for better lighting options. Some models have adjustable f-stops (aperture settings). The lower the f-stop setting, the better your image will be in low-light settings. Shutter speeds are also a consideration. Moving images require a faster shutter speed. 1/60 of a second is the lowest shutter speed for hand-held, stop-motion photography.

Digital cameras vary in how many images they shoot, and how they store them. How you will (in the studio or in the field) and what you will be shooting (still lives or race horses), will be a major factor when deciding what type of camera you purchase.

Consumer and mid-range digital cameras can now store up to 100s of images at a time. There are a number of different types of storage options, memory cards, sticks, and CDs. Memory options are available in many different sizes, the larger the storage device the more images it can hold. Many cameras now come with both memory card and stick slots available.

The cards range from 2MB to 128MB+ storage capacity. How many shots you can store depends on the resolution and compression quality of the image and the size of the card. These cards are reusable but can be a bit expensive. If you will be in the field shooting, larger cards or a camera that saves to an external disk may be the option for you.

Be aware that most cameras have two or more image quality settings (or may use interchangeable memory cards for extra storage space). Images can be set to standard, high quality, and beyond. Standard can range from 320x240 pixels to 640x480 pixels. High quality images can run from 480x240 pixels to 1,024x768 pixels or more. Check each camera manual to see what the manufacturer describes as its camera’s “standard” and “best” resolution. Compare these details before you buy a camera.

Many of the consumer level point-and-shoot cameras use optical viewfinders on their cameras. This means that they have a separate viewfinder that works with the lens but is independent. What this means to you is that what you see in the viewfinder is not what you get in your image. This situation is especially true when you zoom in on an area. Many manufacturers include little bracket lines in the viewfinder to help compose the image. This is why many people who use optical viewfinder often use their LCD screen to compose their shots. Some camera makers have discontinued viewfinders altogether and have bigger LCD screens.

Most cameras have an LCD screen attached to the camera body, which allows you to compose and view your shot instantly. This feature allows you to preview your shots and helps you decide whether to keep it or erase it and shoot it again, without downloading it to your computer first. Some LCDs can swivel, which improves your chances of good shots in tight situations. The problem with LCDs is that you may not get an accurate rendering of the image: the image may look bad on the LCD, but it could be salvageable after it is downloaded. You may find the LCD hard to view in bright sunlight, and LCDs vary in size and brightness. If you will be using the LCD for setting up your shots, look for big bright LCDs. While in the store, look at the LCD in bright sunlight if possible.

Many cameras come with EVF, which acts like a traditional camera viewfinder. It allows you to bypass the LCD screen and see what the camera sees along with the camera settings. Often, when you snap the shutter, a small version of the image will appear in the viewfinder. You also have the added benefit of viewing menu options in it, bypassing the need to use the LCD screen. Both the EVF and LCD use battery power to display the preview image.

Image quality varies from camera to camera, depending upon the size and quality of the CCD, the filter placements, and the interpolation software. The lower the image resolution the higher the likelihood of color fringing on the edges of objects in your image and artifacts appearing in the shadows.

Chromatic aberrations, most often known by its more descriptive name “purple fringing”, can appear on images where high contrast areas meet dark and sometimes mid-tone areas (i.e., a bright sky meets dark mountains, or the side of a brightly lit building meets one in shadow, thin tree branches against sky).

In general, if you"re reducing these images before printing, some or most of the purple fringe will not be noticeable. If on the other hand, you are enlarging the image, the dreaded purple fringe can become very noticeable.

Some cameras handle this problem better than others. The problem is not just with inexpensive models--even the best SLRs (single lens reflex) can suffer from purple fringing.

Basically, 4 types of digital cameras are available to choose from today. Web cams, point-and-shoot, midrange, and digital SLRs. Like traditional photography, it is important to buy a camera that meets your needs and skill level. Do not spend extra money on features you don’t need or will never use.

Point-and-Shoot cameras are available in a wide range of resolutions but are noted for their ease of use. They are usually fully automatic. They often have a range of scene presets to choose from, with few or no manual controls. These cameras are best suited for those who wish to take images with out fussing with controls. If you are considering a point-and-shoot camera, if it is optical, be sure it has a large and bright viewfinder and LCD display.

Midrange cameras come in a wide range of resolutions and offer more features, including scene presets and auto and manual override settings. Some also offer a few more film ASA (American Standards Association) speed options. They usually offer a larger range of image sizes, formats, and compression options than the point-and-shoot models. In most cases, these cameras have accessories that can extend or enhance their performance such as telephoto and macro lens extension kits, the ability to accept an optional flash unit, professional filters, etc. These cameras are for those who are comfortable with photography and who want to have the freedom to override the auto settings. They’re also for those who want to advance their photography skills or move up from point-and-shoot.

Digital SLR cameras are most like traditional professional cameras and feature through-the-lens viewing. What you see in the window is what appears on the picture. They are usually digital camera bodies, and the lens comes separately. The good news is they usually come with one general-purpose lens. They are available in only higher resolutions, offer scene presets, auto settings and lots of manual overrides, and more film ASA options. They also have many options for saving and compressing images. Most often, they have an internal hard drive to store images or the option to attach one. These cameras are not for the point-and-shoot user, and they may be more than the average midrange camera user needs. This camera is aimed at the professional photographer who is making the move to digital or the midrange user who is (or has become) more serious about digital photography.

Digital cameras measure their digital image output in megapixels, which is the total number of pixels in the image. How the pixels are arranged will determine the final size and quality of your final printed image.

For example, I took a picture with my 2.1 megapixel camera. I opened the image in Photoshop and saw that it was 1600 pixels wide and 1200 pixels high. The print dimensions were 22.222 inches wide and 16.667 inches high with a resolution of 72 pixels per inch. My printer works best with print resolutions of 260 or 280 pixels per inch. So, I need to rearrange the pixels to get the best output.

When I change the image resolution in Photoshop to 280 pixels per inch in the resolution control box, the image height and width change to 5.717 inches by 4.286 inches. The total number of pixels stays the same but are now reorganized based on the desired output.

Your printer’s resolution and the size images you want to print are important factors to keep in mind when deciding on pixels. The more pixels you have to work with, the larger and crisper the images you can create. When larger output is your most important consideration, in most cases, the more pixels you can afford the better. If you don’t print larger format prints, or if you only use your images for online distribution, a less expensive model with fewer pixels may make better sense for you.

More pixels also come in handy if you crop your images using computer software. With a larger number of pixels, you can crop out some of the image and still have enough pixels for a large printout. You may not be able to get a full size print of the original image before your edit, but depending on the amount of your crop, you could get pretty close.

When reading the manufacturer’s information about their cameras, you will often see “optical” and “digital zoom” listed in the features. Often the optical zoom will be a lower number and than the digital zoom.

The difference between optical and digital is really very simple: It’s just what it says it is. Optical zoom is the base level of zoom that the lens can zoom in and out. With digital zoom, the camera tries to increase zoom range by cropping the image previewed in the viewfinder. Once cropped, it blows that area up as if you zoomed in closer. It is a bit like interpolation on scanners. While the extra zoom possibilities seem great, the images employing this feature usually come out soft (blurry) and can become very grainy.

Digital cameras devour batteries. Some companies package recharger kits with the cameras, others offer them as an extra purchase. In the long run, you would do well to invest in the recharger kit and purchase three sets of rechargeable batteries. This set up allows you to have a set in the charger, a set in the camera, and a replacement set charged and ready to go.

You can save your battery life by taking photos and selecting the camera’s options setting using menu options through the viewfinder, not the LCD monitor. Another good habit to get into is not to rely on battery power to download your images to your computer. Use your power adapter when downloading images to your computer whenever possible, or better yet, use a card reader.

Most cameras come with software and connections for both Macintosh and Intel-based computers. Most cameras save in JPEG or TIFF format, or its downloading software will convert the image to your favorite format.

Generally the options are TIFF for uncompressed files and various degrees of JPG compression. These settings are referred to as normal, fine, superfine, and good, better, or best. The more compression applied, the smaller the file size; therefore, more photos can be stored on a card. With high compression, digital artifacts and lost details can occur. When less compression is applied, fewer images can be stored on the card, but there are fewer JPG artifacts in the image.

Most manufacturers use a middle of the road setting of “better” or “fine.” Unfortunately these terms are not standardized. What is better on one camera may be good or best on another. Be sure to research these differences before buying a camera.

Many of the newer model cameras are able to use two or more types of memory cards. This is a very nice feature that some camera companies are using as an enticement to switch camera makers. This set up enables you to use your older style memory cards preferred by the other camera maker (and that you have lots of money invested into), in your new camera. Some of the higher-end cameras come with a small hard drive or can accommodate one. Some cameras also burn files directly to CD storage.

To make downloading easier, you can purchase a handy device to read your memory cards. You insert your memory card into the device and it is reads the files like an external hard drive. Some of these devices come with the ability to accept multiple types of cards. These units are very handy when you have more than one camera type in a household or office environment.

Older models of card readers came in the shape of floppy disk. You inserted your memory disks into the reader. The reader then was inserted into the computer’s floppy drive and appeared on the desktop just like a disk.

A number of printers on the market are made specifically for digital camera output. Some come with card readers built in. The best for photo quality images at this point in time are inkjet and dye sub technologies. Sometimes the camera manufacturer will recommend an appropriate printer for the camera.

There are printers with inks sets ranging from 4 to 8 color ink cartridges. Some of the colors are packaged in one cartridge and others come packaged individually. Six or more color inks will give you optimal color reproduction. Additionally, the higher the resolution of the printer, the more photo-real the printed image can appear. Of course if your image is a large image, with a 72-pixel resolution, then higher printer resolution will probably be wasted, and the image will appear dotty and pixilated.

Some companies have made archival inks available which are waterproof, and according to the manufacturers, can last as long as 100 years on the right paper and under the right lighting conditions. These inks usually need to be used with higher-end papers, which are sometimes referred to as professional papers. If used with lesser quality papers, they may not be waterproof, or light safe, and the colors may be inferior and contain colorcasts.

Dye sub printers are very different from inkjet printers. The ink is joined to the paper in a sublimation process, and become one. This technique usually an expensive option, as you have to use a paper that the special inks can be sublimated to. The paper and inks are not easily available in stores. But, the output can be very good when the image resolution is matched to the printer.

Always remember that in most cases the printer will NOT be able to accurately reproduce on paper the colors on your screen. Monitors and inks have an altogether different range of colors, known as color gamut. Please study this very important issue before you spend lots of time, ink, paper and money, only to end up frustrated with your image output. That said, many of the newer model printers are doing a great job fixing gamut problems with their software. It is important to read the manual to set up the printer for the best possible output. Always take notes about your settings if you change them. If you’re happy with the image, and you want to reproduce it a month or two later, you’ll know what settings you used.

Keep in mind that if you are just buying a photo printer exclusively for your digital images, and will not be printing 8x10 or larger images, or if your camera can’t create acceptable output at those sizes, you don’t need to buy an 8x10 or larger format printer.

The great news about photo printers is that they are getting cheaper every day. The replacement inks and paper supplies are another matter altogether.

Fujifilm has unveiled its new high-end APS-C camera, the X-H2S. It arrives four years after the X-H1 and it’s not alone, because Fuji also announced the 40MP X-H2 a few months later, which means there are now two flagship models: one that focuses on resolution, and one that is all about speed.

The latter is the one we’re going to talk about in this article, and we’ll do so by analysing how it compares to the product that, until recently, was the best the company had to offer: the X-T4.

Ethics statement: the following is based on our personal experience with the X-T4 and X-H2S. We were not asked to write anything about these products, nor were we provided any compensation of any kind. Within the article, there are affiliate links. If you buy something after clicking one of these links, we will receive a small commission. To know more about our ethics, you can visit our full disclosure page. Thank you!

The 10 Main Differences in a NutshellDesign: the iconic exposure dials may be replaced by the default shooting mode dial, but the X-H2S provides a much better grip and improved customisation possibilities. It’s a question of personal preferences, but if you use a large lens like the XF 100-400mm, you’ll prefer the S model.Viewfinder / LCDs: the X-H2S has a better viewfinder in almost every way, and the top LCD is large and very useful. The touch rear monitor is the same on both.Memory cards: if you want a second memory card to back up the SD card, prepare yourself to spend more money because you’ll need one CFexpress Type B. But the latter is needed for the best video settings, and also provides better continuous shooting performance.Battery life: they use the same type and there is little difference in real world use. How long it lasts depends on whether you activate the boost mode or not. The X-H2S has two battery grip options.Sensor: same resolution, same ISO range, but the one on the S model is stacked and offers a faster readout. That comes at the cost of more noise in the shadows, but you’ll need to recover the exposure by four stops or more to see a relevant difference. The colour palette has also been tweaked slightly on the new camera.Drive Speed: the X-H2S does 40fps without a sensor crop, improving the 30fps with 1.29x crop mode of the X-T4. The buffer is also much better.Autofocus: there is an improvement to face and eyed detection for humans. The new subject detection mode is a welcome update, but it’s not 100% reliable (at least with birds and animals, I have not tested the other options). The keeper rate for birds in flight is about the same, which means the new camera doesn’t bring a substantial improvement over the X-T4.Video: the X-T3/X-T4 were already better than many competitors when it comes to video specs, but the X-H2S goes miles further: 6.2K, 4K 120p, unlimited recording, lots of file formats and minimal rolling shutter.Stabilisation: the X-H2S does a little better overall, but it will hardly make a difference in real world use.Price: the X-H2S is more expensive.

The X-H2S is larger and heavier than the ‘T’ model, but not by much. Both cameras are built with magnesium alloy plates and are weather-sealed, including freeze proofing down to -10˚C. The X-T4 is available in black or silver, whereas the X-H2S comes in black only.X-H2S: 136.3 x 92.9 x 84.6mm, 660g

The most notable difference in terms of design is the front. Just like its predecessor the XH1, the X-H2S sports a larger grip to give photographers a more comfortable hold when using large lenses such as the XF 100-400mm, or the new 150-600mm.

The other relevant difference concerns the physical controls. The S model has a more standard design, with a shooting mode dial on top and various buttons dedicated to ISO and other key settings.

The buttons have been refined to improve their operation: they are more rounded and give you better feedback, whereas I find many buttons on the X-T4 to be too flat and small. The AF joystick is also better on the S model: it’s larger and more precise to use.

The X-T4 comes with the traditional layout Fujifilm is known for, which mimics old SLR film cameras. You have a dedicated dial for the shutter speed and ISO, and sub-dials to control other parameters such as the drive mode, or to switch between stills and video. There is also a focus mode selector at the front.

The front / rear command dials are similar, although the one on the back of the X-H2S is a bit larger. That said I struggle with its precision – I often find myself turning it and nothings happens on the camera screen for the first few seconds (especially when using exposure compensation). A subscriber on my YouTube channel told me firmware 2.0 has fixed this.

The two cameras share the same size when it comes to the viewfinder’s electronic panel, but other characteristics such as resolution and magnification are in favour of the S model.

I certainly enjoyed using the EVF of the X-H2S: the increased magnification, resolution and the overall quality are worthy of a flagship model. It’s not game changing in comparison to that of the X-T4, but you’ll appreciate the upgrade. I wear glasses and I couldn’t see the four extreme corners despite the generous eyepoint, but it wasn’t an issue for me.

As for the rear monitor, it is the same: 3.0-in with 1.62M dots and touch sensitivity. You can interact with the Quick menu, move the AF point, take a shot or change a setting by flicking left, right, up or down.

What will drain your battery faster is the Boost setting. In addition to giving you better resolution, or a higher frame in the viewfinder (like I explained earlier in the article), it also improves the autofocus performance, and indeed I find the AF quicker and more reactive with this setting turned on. You need to keep this in mind if you want to turn off the Boost mode, or activate the economy mode. The alternative is to carry spare batteries, or use a battery grip.

Speaking of the battery grip, there is one available for both products, and Fujifilm has designed a second one for the new camera called FT-XH. It features a built-in LAN port for high-speed file transfer while shooting. It can also work with a wireless LAN connection. It is much more expensive than the regular grip however ($1K).

The two cameras share the same format (APS-C) and resolution (26.1MP), but the sensor found inside the X-H2S is a new version. Fujifilm calls it X-Trans CMOS 5 HS to signal the fifth generation (HS stands for High Speed), as opposed to X-Trans CMOS 4 for the X-T4.

The most important difference is the design: while both are BSI (back-side illuminated), the sensor in the new camera is stacked, and has a 4x faster reading speed in comparison to that of the X-T4.

The stacked sensor, coupled with the new X-Processor 5 engine (twice as fast as the X-Processor 4 found on the X-T model), give the X-H2S superior capabilities when it comes to video, drive speed and more, as you’ll discover further down.

I was curious to see if there would be any difference in image quality between these two sensors. I started with the dynamic range test and, at first glance, they perform in the same way: same amount of details recovered in the highlights, and the shadows are clean with very little noise.

The image above shows a 2 stop exposure recovery for the shadows, which is not a very stressful test for a modern digital sensor. If I underexpose the scene further, and try to recover the exposure by four stops, a difference emerges: the X-H2S produces more noise and loses more details in comparison to the X-T4 (look at the neck of the stuffed toy).

Up to 12,800 ISO there is nothing worth highlighting: the results are comparable. If we really pixel peep, we can see that noise on the X-T4 is a bit smaller, but it really is a tiny difference.

When looking at the extended ISO, the X-H2S shows less colour noise in comparison to the X-T4. This shows an improvement to the new image processor and updated software on the new camera.

You may have noticed a difference in colour: the X-T4 has more yellow, which is especially noticeable on the doll’s face. For both files, I left most of the default settings on Lightroom, including the Adobe Colour profile, and I matched the WB and Tint parameters. Of course, these being RAW files, colours can be easily matched and they can also change according to the photo editor you’re using and its own distinctive profiles.

To dig more into this, I looked at some straight-out-of-camera JPGs with the portrait of yours truly. The difference is more subtle, but there is slightly more yellow in the skin tones of the X-T4 version, whereas the X-H2S adds a bit more red.

The X-H2S increases the maximum drive speed to 40fps, without any crop. This means that the fastest speed is available with the full sensor area, and therefore the full resolution.

With the electronic shutter and fast drive speeds, both cameras work with live view and no blackouts, which is great for following difficult and unpredictable moving subjects.

Thanks to its stacked sensor and faster processor, the X-H2S has an advantage concerning the rolling shutter, when using the electronic shutter: distortions when panning quickly are much more contained than on the X-T4.

Then, we have the buffer capabilities. On paper, the X-H2S looks impressive, with more than 1,000 JPG or RAW up to 20fps, versus the 79 JPG and 36 RAW of the X-T4.

I did some tests and indeed, the X-H2S is in another league. The best results come when using CFexpress cards, not so much for the initial buffer, but because they allow the camera to keep a faster frame rate after the buffer is full.

Fujifilm has published a compatibility list of recommended memory cards. It also highlights which of these cards give you no compromise in performance, including when shooting in continuous mode. Among those cards, we find the Lexar Diamond and Lexar Gold series, but not the Sandisk Extreme Pro. In my test, the difference only showed up when testing uncompressed RAW, and you can see the results below.

With SD cards, the performance drops a little but remains really good on the X-H2S. For example at 40fps, you’re still able to record at full speed for 4 seconds, and the speed afterwards is similar. It is at lower speeds than the SD card loses its edge against the CFexpress card.

The X-T4 has a much more limited performance. The camera can’t go past 1 second at full speed with 30fps when using RAW, and 2 seconds when using JPGs. The buffer improves only marginally at slower speeds, and the frame rate once the memory is full is always below 10fps.

The total number of autofocus areas remains the same on both cameras: 117 points (Zone and Tracking) or 425 points (single area mode). In low light, the official rating is -7EV for both (measured with the XF 50mm F1.0).

The improvement on the X-H2S is found in the software, which has a more advanced algorithm and deep learning technology. The S model can detect a variety of subjects including animals, birds, cars, motorcycles and airplanes, as well as boosting the performance for human subjects (face and eye detection).

The subject walked back and forth facing the camera, and then walked while spinning around (to see how the camera keeps tracking when the face is hidden).

The X-T4 struggles more, with a few extra out of focus images and more slightly soft results. But as far as AF behaviour goes, there isn’t a relevant difference between the two products. They both managed to follow the subject even when she was not facing the camera.

With birds in flight, I tried different setting combinations, but my best keeper rate would’t go higher than the one you see below, which is no improvement over the X-T4, and only slightly better than the X-S10. To note, the drive speed on the S model (20, 30 or 40fps) didn’t influence the results.

The two cameras struggle to keep the bird sharp at all times because A) they have the tendency to confuse it with a busy background (trees, fields etc), and B) they struggle to maintain optimal sharpness, causing many images to be slightly soft.

Of course the score above is far from poor, but it also shows no real improvement over previous models, despite the claim from Fujifilm that the X-H2S is three times faster, with an AF calculation of 120 fps (vs 40fps on the T model), which is supposed to improve the speed and precision of autofocus and exposure tracking.

The X-H2S can record 6.2K up to 30p in the 3:2 aspect ratio (also known as ‘open gate’). It can work in 4K up to 60p with the full width of the sensor, and 4K 120p with a 1.29x crop. It can also record internally with the Apple Prores codec (HQ, 422 and LT).

The X-H2S offers a great list of file formats and compression options. The highlight is the possibility to record Apple Prores, a popular codec for all filmmakers who edit on a Mac. That said, Prores has a very high bitrate and you’ll need CFexpress cads with large capacity if you want to record for a long time. For example, a 128GB memory will save approximately 9 min of Prores HQ recording.

There are certainly other ways to record vertical videos, like positioning your camera vertically and flipping the footage in post (more and more cameras can save the orientation in the metadata as well). But the advantage is being able to record one format that can be used for different outputs with more flexibility. If you record with your camera in vertical mode, you won’t have the chance to use that same footage horizontally without a severe crop.

In terms of image quality and sharpness, both cameras deliver the same results in 4K. Obviously, another advantage of recording 6.2K is being able to zoom in on your footage in post on a 4K timeline and maintain an excellent level of detail.

You can see the difference with the simple test below, where I magnified the footage by 300%, which is more than you’ll ever need. Look how clean the details are on the two white boxes on the left, compared to those on the right.

The X-H2S has a new Log profile, F-Log2, which promises more dynamic range (14+) in comparison to F-Log (12 stops). In my test though, I could see few differences between the two curves. F-Log2 is more flat, with less contrast and a bit more saturation, but the amount of details in the shadows and highlights remains very similar.

If needed, you can change the Auto Power Off Temp. setting to High in the menu to let the camera record for longer. Fujifilm also designed an optional cooling fan for the most demanding specs and the warmest locations.

In my experience, the X-T4 can overheat and shut down after approximately 60 minutes (two consecutive clips), when recording 4K 25p with a similar ambient temperature.

Autofocus has improved on th

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey