bmw tft display retrofit free sample

That said with the issues that guys seem to be having, although a software update is supposed to be helping that issue, it does not interest me in the least Just as I could do without keyless start, I can do without the TFT.

That’s what the BMW S 1000 RR is in a nutshell — blistering speeds, top-of-its-class specification at varying times (at times the most powerful, at times the lightest), completely beautiful, and still with comfort and keep-alive features that make it the best “everyday superbike” — if there can be such a thing.

Yes, yes it is. I lust after the S 1000 RR. If you’re not sure you can lust after a BMW (some people tell me “Never a BMW!” as their impression is they still produce bikes that feel like tractors), then go watch this scene from Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, put your qualms about all those extended head checks (and celebrities’ personal lives) to one side, and just enjoy the well-filmed knee-down action.

BMW surprised the motorcycling world when they released the first BMW S 1000 RR in 2009. It really changed how everyone perceived the brand — which was just what BMW intended.

BMW was at that point known for boxer twins and big sport tourers, with some (like the HP2 or the K 1300 S) getting pretty sporty, but nothing close to being a Superbike World Championship (WorldSBK) competitor.

But the S 1000 RR was just that, a full-on sport bike intended to compete in WorldSBK. Borrowing heavily from the Japanese playbook, the BMW S 1000 RR has a familiar sounding spec sheet: a 999 cc inline four-cylinder engine with dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder, producing lots of power above 10000 rpm.

By the way, “S 1000 RR” is written like that — with spaces. People often write S1000RR or affectionately S1KRR or just RR (which is confusing as Honda CBR1000RR and CBR600RR owners use the same shorthand). Anyway, I don’t get hung up on naming conventions or care at all, but just am sticking to BMW’s convention.

Also note: From 2021, BMW has another motorcycle in the same range called the M 1000 RR. It’s part of the same range, but more intensely track-focused.

So why did BMW make the first S 1000 RR? Simple: To compete in and win the Superbike World Championship (WorldSBK), the world’s premier racing class for “production” motorcycles.

Why enter the sportbike market at all? According to Hendrik von Kuenheim, the then second-generation president of BMW Motorrad, it was partly a business decision. “Some eighty five thousand 1000cc sportbikes are sold per year worldwide, and we want to gain a foothold in that segment,” he told the press. BMW’s goal was to get a 10% market share, mostly through stealing share from the dominant competitors.

So that was why BMW chose WorldSBK and not MotoGP. Per Markus Poschner, BMW’s General Manager for the K and S series platforms, BMW chose to enter WorldSBK “… because it is the same bike racing that you can buy.”

But before this, you’d be excused for thinking BMW would never even build a superbike. Project leader of the BMW S 1000 RR, Stefan Zeit, recalled: “When I started at BMW, I had an interview with Markus Poschner, and he asked me, ‘What should BMW do next?’ I told him a sportbike, and he said, ‘No, BMW will never do this!"”

Poschner himself was a sportbike fan, though. He confessed that he had always dreamed of these bikes since starting at BMW, even though he didn’t think BMW would go in this direction.

Since building a superbike was a new thing for BMW, they had to benchmark the competition. There was no suitable internal benchmark. The bike they picked was the 2005-6 Suzuki GSX-R1000, known now affectionately as the K5.

In 2008, Peter Müller, BMW’s VP of Development and Product Lines, surprised everyone by announcing at the Mondial du Deux Roues Motorcycle Show in Paris that BMW would enter a factory team into the 2009 WorldSBK.

“In 2007 BMW returned to road racing with the sports boxer after more than 50 years. In 2008 we will continue our activities in the Endurance category. At the same time we will be preparing our entry into the Superbike World Championship in 2009 with great intensity.”

(2007? What “sports boxer?” He was talking about the BMW HP2, a race-tuned BMW R 1200 S. And the Endurance was the HP2 Enduro, a kind of stripped-down R 1200 GS.)

In that year, BMW came sixth in the manufacturer titles. Ducati won. Kawasaki, who came seventh, went on later to win for many years with their revamped ZX-10R.

BMW just wanted to play in 2009, but in subsequent years, they haver had a factory win, though they came close in 2012 by coming second. At the end of the 2013 season, they terminated their factory involvement, saying they wanted to focus on consumer bikes.

If you look at the BMW S 1000 RR and compare it to most other superbikes you may think it’s just another 1000cc inline four-cylinder engine in a sportbike chassis with USD forks and so on.

All the other manufacturers’ production literbikes peaked in power before 12,500 rpm, whereas BMW peaked at 13000 (or a shade over, per the dyno). BMW got to these high RPM figures with a high-speed, extra-sturdy valve drive with individual cam followers and titanium valves.

Akrapovič, the exhaust manufacturer, did its own apples-to-Äpfel dyno comparison. The order is very slightly different, but BMW is still on top in both metrics.

More importantly, the S 1000 RR’s broad torque curve became a well-loved feature — something BMW learned, no doubt, partly from studying the K5 GSX-R1000’s virtues.

The 2009 BMW S 1000 RR was a rare production superbike with optional ABS and Dynamic Traction Control, which is traction control that takes lean angle (and later, cornering acceleration) as an input.

BMW’s system was unique in that it was lightweight, weighing only 2.5 kg / 5.5 lb. Other brands (e.g. Honda with its CBR1000RR) had ABS as an option, but it was less often chosen because of the considerable added weight (up to 10 kg / 22 lb).

Ducati was also very early in 2012 with acceleration-aware traction control from the IMU. Other brands were earlier with cornering ABS, but when BMW made it an option in 2017, it was retrofittable back to 2012, thanks to the advanced hardware.

Not everyone likes it, of course, and BMW ditched it in the 2019 generation. I would be more dismayed if the 2019 gen didn’t look so good. (Pics below in that section!)

The BMW S 1000 RR hasn’t changed fundamentally since its launch. It has always had a 999cc liquid-cooled 16-valve inline four-cylinder engine making north of 140 kW (190 hp).

The DTC on the first-generation BMW S 1000 RR was advanced for the time. Depending on the ride mode you were in, it worked by interrupting power based on the angle at which the bike was leaning.

BMW’s DTC system from 2012 onward takes input from more advanced sensors. The sensor array is good enough that you can retrofit 2012+ models with “ABS Pro”, BMW’s name for cornering ABS, when it became an option from 2017, via enabling codes (see this guide, which discusses the retrofit option).

BMW refined the way DTC worked intervened, allowing more slip in race and slick modes. Slick mode deactivates wheelie control altogether in the 2012 model, whereas in the first gen, slick mode let you do wheelies of up to five seconds.

The second gen still had an asymmetrical headlight design and the analogue tachometer. But BMW improved the display for better legibility of the speed display, also letting you dim it, and adding more functions like “best lap in progress” or “speed warning” if you need it.

The BMW HP4 is a race-focused bike, released in mid 2012 (see press release) for the 2012-2013 model years. It’s distinct from the BMW HP4 Race which was released in 2017 for that year only (see below).

The HP4 is technically a successor to the boxer-powered HP2 Sport, which in turn had more in common with the boxer sport bike the BMW R 1200 S. But the HP4 is the first four-cylinder HP bike.

The BMW HP4 is heavily based on BMW S 1000 RR. It shares the inline four-cylinder engine, with the same specs on paper, but with tuning to increase midrange torque between 6000 and 9750 rpm. The engine also has the same throttle response and full power output in all ride modes (but other characteristics change, like ABS/traction control).

But the BMW HP4 is much lower weight (199 kg DIN unladen, vs 206.5 kg for the 2012-2014 S 1000 RR, both including ABS), due to lighter 7-spoke forged alloy wheels, a lighter sprocket carrier, a lighter battery, carbon parts, and a lighter titanium exhaust.

The DDC system doesn’t just measure speed and acceleration/ deceleration. It takes input from an IMU that can also feed it information about pitch and lean angle. Because the BMW HP4 has an IMU already, BMW offered in 2014 the ability to retrofit these bikes with cornering ABS (ABS Pro in BMW nomenclature).

BMW also added Race ABS with an enhanced “slick” mode. The internal “IDM” setting configures Race ABS with specific parameters, obtained from experience on the track, to optimise the HP4’s ABS for track use.

In late 2014, BMW announced a new revision for the S 1000 RR for the 2015 model year, with more power again, a slight weight reduction, and a host of technological features, which would be improved upon again slightly in 2017.

But BMW didn’t just improve top-end power; they focused on producing a broad spread of torque from 5000rpm all the way up to 12000 rpm (though not as impressive as the even flatter torque of the 2019+ ShiftCam engine).

BMW added a “Race Package” from 2015, which gave the user DDC (a more advanced version, from the HP4), launch control, a pit limiter, and cruise control.

In 2017, BMW made a small change to the S 1000 RR when they made cornering ABS (which BMW calls ABS Pro) standard. Shortly afterwards, BMW made ABS Pro available as a retrofittable option to earlier models from 2012 onwards. (Many took them up on this as it only cost around 400 Euro/500 USD — check that “ABS Pro” shows up on the dash if you’re buying a used one.)

Finally, I prefer the analogue white-faced tachometer of the Gen 3 S 1000 RR. This is a personal preference. The TFT on the Gen 4 is great looking, but ultimately, it reminds me too much of my phone and of technology — something I’m trying to leave behind when I’m riding (or taking part in any kind of leisure).

The BMW HP4 Race is another race-focused version of the BMW S 1000 RR, an evolution of the BMW HP4 made between 2012-2013. Only 750 were made, all in the year of 2017.

Unique Rider aidsStandard ABS, ABS Pro (optional), Optional quickshifter, Ride modes (street oriented, optional customisable)HP Shift Assistant Pro, DTC (later intervention), EBR(+/-7), 4 customisable ride modes, data loggers, dash with mechanic sideBMW S 1000 RR Gen 3 (2017-2019) vs BMW HP4 Race core differences

The engine itself is hand-crafted by a small team of experts at BMW in Berlin. There are a number of changes that contribute to its increased power and torque:

In case you were wondering, yes, the BMW S 1000 RR in 2019 is both more powerful and lighter — in fact, the weight of the S 1000 RR is the lowest it has ever been. With the M package it’s an absurdly low 193.5 kg.

Aside from power and weight, another marquee features of the 2019+ BMW S 1000 RR is that ShiftCam engine. ShiftCam is BMW’s name for variable valve timing (VVT). The tech means that they alter the valve timing and stroke, allowing the engine to breathe differently depending on its load.

BMW also made chassis improvements in the Gen 4 BMW S 1000 RR. They implemented what they call the Flex Frame, increasing the load-bearing function of the engine, and improving the ergonomics as a result, by

The 2019 BMW S 1000 RR has different brakes to the earlier versions. They’re no longer made by Brembo and are now made by Hayes, an American company (owned by Brembo), apparently chosen after blind testing. The rear caliper is still made by Brembo.

Note — BMW recalled the Hayes calipers S 1000 RR. The calipers may leak when parked. It’s slowly and doesn’t cause the brakes to fail, but riders would notice fluid marks on the rim, tire, or ground. As part of the recall, the caliper would be replaced by the same Nissin caliper that came standard in the 2021+ models.

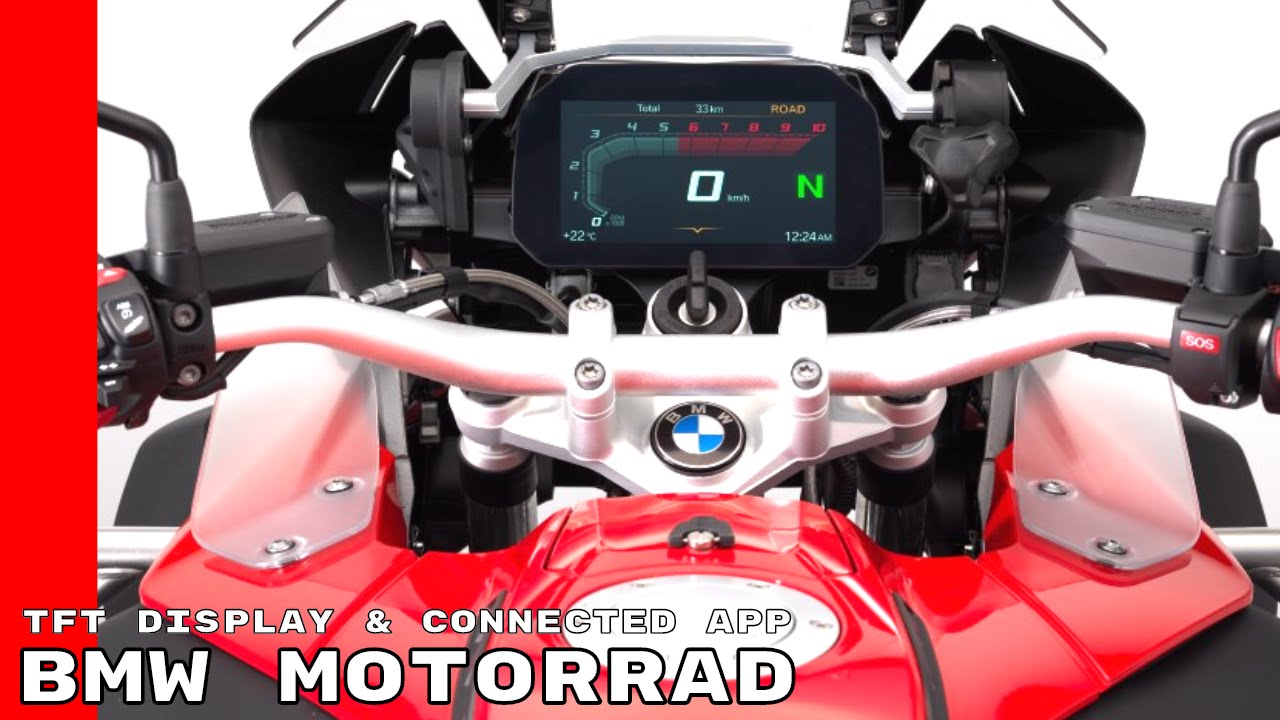

BMW also changed the analogue tach + LCD to a full-colour TFT display. While it looks cool and clean, I will miss the white dial. (Am I already old? Perhaps I’ve just dropped too many a phone and see all screens as fragile… in reality, I’ve also had CAN bus bikes fail to start when an analogue tacho was broken.)

From late 2020, the latest BMW S 1000 RR has also been available with the M Endurance chain, a low-maintenance chain with a very hard diamond-like coating on the rollers. See more about the M Endurance chain here.

Anyone familiar with motorsports would be familiar with the iconic M range from cars — the BMW M3, M5 and so on. Well, 2021 is the first year that the M range has included motorcycles. Remember this and tell your (or someone else’s unwitting) grandkids!

The 5th gen BMW S 1000 RR has the same ShiftCam engine as in the 4th gen BMW S 1000 RR, but BMW has implemented a few things from the M 1000 RR (which came after the 4th gen), including

BMW added a new tech feature of “Slide control” to the 5th gen S 1000 RR. Just in case you didn’t feel like enough of a superhero with the IMU that the S1KR has had since the 3rd gen, BMW added a steering angle sensor to help control how you power slide!

Here’s how slide control works. The BMW IMU / ECU interprets measures slip angle and compares it with the set value per the DTC settings. If the computer thinks you might go past maximum slip, the slide control system moderates the amount of drive to limit slip.

Improve Shift Assistant Pro. BMW improved the quickshifter, implementing your shift request via a “torque model” and thus letting you use it in all situations. They also improved the mechanism. It’s now easier to change to race shifting, too.

BMW also refined the chassis geometry, flattening the steering head by 0.5 degrees to 66.4 degrees rather than 66.9, and reducing the offset of the triple clamps by 3 mm. The goal of this, and a few other changes, is to subtly improve riding position and feedback from the front wheel.

Yamaha YZF-R1 “Crossplane”. Yamaha has been making its crossplane crankshaft-equipped R1 since 2009 too, coincidentally. The 2015 version was built for even more power, and got a six-axis IMU with cornering ABS, two years ahead of the S 1000 RR (which got it in 2017, retrofittable to 2015). You’d pick the R1 for that unique engine and sound and for even wider service intervals (40000 km +). The R1 never got heated grips or cruise control.

Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade. Since the first 2004 CBR1000RR, Honda has always been a bit lower on the power and features than its competitors, only getting an IMU as of the 2017 model year for example. You’d pick the Honda if you’re after legendary Honda reliability or if you’re tickled by the history of the Honda FireBlade. But otherwise it stacks up comparably with the S 1000 RR on power and torque delivery, and the BMW outclasses it in tech and functions. As of 2021 though, the CBR1000RR-R SP is a very expensive and exclusive bike.

Aprilia RSV4, RSV4 R, RSV4 Factory, RSV4 R APRC, RSV4 RR. You’d buy an Aprilia RSV4 if you want a V4 engine. It’s an incredible machine. You give up a bit in terms of comfort — it’s smaller, with a more aggressive position. In recent years the 1100cc RSV4 has been more powerful AND lighter than the BMW S 1000 RR. Cornering ABS and cruise control since 2017.

Suzuki GSX-R1000. Another iconic sportbike — recall that the 2005 model was a primary inspiration for the first S 1000 RR. The latest 2017+ Gixxer is comparable in power (150 kW/202 hp) and weight (201 kg/443 lb) with the latest S 1000 RR. The 2017+ Suzuki superbike has quite an advanced engine too, with variable valve timing equipped. But the latest standard Gixxer lacks cornering ABS (despite having an IMU for traction control), uses a full monochromatic LCD rather than TFT, and doesn’t come with even a shock quickshifter. The higher-spec R model does have cornering ABS, bi-directional quick shifter, but not fancy features like cruise control or heated grips.

Spec2017-2018 BMW S 1000 RR2017-2018 BMW S 1000 R2017-2020 BMW S 1000 XRPower145 kW (199 hp) @ 13,500 rpm121 kW (165 hp) @ 11000 rpm121 kW (165 hp) @ 11000 rpm

If you’re buying a used BMW anything, make sure you buy one with a complete maintenance log. BMW buyers can be quite fussy and expect the log to be complete.

If it’s the former, it’s resolvable, and BMW may do it themselves on their coin. But if it’s a problem with the camshaft, it’s higher risk, and there are some stories of engine failures. If the top-end is noisy and the previous owner hasn’t resolved it, it would be safer to walk away, unless you’re confident you can resolve it yourself..

Used TFT clocks DIM from S/V60, XC60, S80II, XC/V70III made in the years 2014 to 2017 (the unit from V40 series can only be used in V40 cars - it has different mechanical shape than x60, x70, x80)

make sure that you located the TFT DIM that matches the transmission type of the target car - Automatic (PRND display) or Manual (+ Gear -) on the right side of the display. Diesel/petrol fuel type of the donor car does NOT matter.

Then press DECODE CEM. We must warn you this process can take up to 24 hours(but on average it usually does not take more than 12 hours). During the whole process you can interrupt the decoding process and continue later. If you do the CEM PIN decoding then you no longer need to do it again. Thanks to this you can also make other changes in the vehicle configuration including the TFT retrofit. After this process is done you will receive an email to the account you put in in the beginning.

Then choose CAR CONFIGURATION and then “Car configuration wizard”. Then you only need to choose the “TFT retrofit” wizard. Make sure DIM is connected.

Connect DiCE again, turn the ignition key to position II and open VDASH again on your computer. Go to “Car configuration wizard” and choose TFT retrofit again.

VDASH will begin to look for the newly connected TFT DIM. If all wires are correctly plugged in, the update process will begin. If not then check the connecting of the wires again using the multimeter.

Your vehicle will restart itself many times during the process and at the end you will see a picture of the vehicle, the state of fuel and more. At the very beginning the incorrect measures can be displayed, but after a short trial run it should be fixed. The kilometres will also automatically reappear.

You can change and move the clock motivesonly when the engine is running (this does not have any specific explanation). The designated motive is Elegance(grey or brown). It is possible to reprogramme this motive to a blue version “R-design” (using car configuration > advanced settings > Advanced TFT DIM settings > Screen Skins > DIM: R-design menu), motives Ecoand Powerremain unchanged.

1. Temporarily disconnect newly connected cables from the white DIM connector, and connect the original DIM2. Start the engine (SCL the steering lock will now unlock)3. While the engine is running, disconnect the original DIM connector and reconnect the additional wiring, connect the TFT DIM4. Turn the engine off and lock the car5. SCL will NOT turn on again (unless you connect the original DIM). You will not observe any further immobilisation issues.

That’s what the BMW S 1000 RR is in a nutshell — blistering speeds, top-of-its-class specification at varying times (at times the most powerful, at times the lightest), completely beautiful, and still with comfort and keep-alive features that make it the best “everyday superbike” — if there can be such a thing.

Yes, yes it is. I lust after the S 1000 RR. If you’re not sure you can lust after a BMW (some people tell me “Never a BMW!” as their impression is they still produce bikes that feel like tractors), then go watch this scene from Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, put your qualms about all those extended head checks (and celebrities’ personal lives) to one side, and just enjoy the well-filmed knee-down action.

BMW surprised the motorcycling world when they released the first BMW S 1000 RR in 2009. It really changed how everyone perceived the brand — which was just what BMW intended.

BMW was at that point known for boxer twins and big sport tourers, with some (like the HP2 or the K 1300 S) getting pretty sporty, but nothing close to being a Superbike World Championship (WorldSBK) competitor.

But the S 1000 RR was just that, a full-on sport bike intended to compete in WorldSBK. Borrowing heavily from the Japanese playbook, the BMW S 1000 RR has a familiar sounding spec sheet: a 999 cc inline four-cylinder engine with dual overhead cams and four valves per cylinder, producing lots of power above 10000 rpm.

By the way, “S 1000 RR” is written like that — with spaces. People often write S1000RR or affectionately S1KRR or just RR (which is confusing as Honda CBR1000RR and CBR600RR owners use the same shorthand). Anyway, I don’t get hung up on naming conventions or care at all, but just am sticking to BMW’s convention.

Also note: From 2021, BMW has another motorcycle in the same range called the M 1000 RR. It’s part of the same range, but more intensely track-focused.

So why did BMW make the first S 1000 RR? Simple: To compete in and win the Superbike World Championship (WorldSBK), the world’s premier racing class for “production” motorcycles.

Why enter the sportbike market at all? According to Hendrik von Kuenheim, the then second-generation president of BMW Motorrad, it was partly a business decision. “Some eighty five thousand 1000cc sportbikes are sold per year worldwide, and we want to gain a foothold in that segment,” he told the press. BMW’s goal was to get a 10% market share, mostly through stealing share from the dominant competitors.

So that was why BMW chose WorldSBK and not MotoGP. Per Markus Poschner, BMW’s General Manager for the K and S series platforms, BMW chose to enter WorldSBK “… because it is the same bike racing that you can buy.”

But before this, you’d be excused for thinking BMW would never even build a superbike. Project leader of the BMW S 1000 RR, Stefan Zeit, recalled: “When I started at BMW, I had an interview with Markus Poschner, and he asked me, ‘What should BMW do next?’ I told him a sportbike, and he said, ‘No, BMW will never do this!"”

Poschner himself was a sportbike fan, though. He confessed that he had always dreamed of these bikes since starting at BMW, even though he didn’t think BMW would go in this direction.

Since building a superbike was a new thing for BMW, they had to benchmark the competition. There was no suitable internal benchmark. The bike they picked was the 2005-6 Suzuki GSX-R1000, known now affectionately as the K5.

In 2008, Peter Müller, BMW’s VP of Development and Product Lines, surprised everyone by announcing at the Mondial du Deux Roues Motorcycle Show in Paris that BMW would enter a factory team into the 2009 WorldSBK.

“In 2007 BMW returned to road racing with the sports boxer after more than 50 years. In 2008 we will continue our activities in the Endurance category. At the same time we will be preparing our entry into the Superbike World Championship in 2009 with great intensity.”

(2007? What “sports boxer?” He was talking about the BMW HP2, a race-tuned BMW R 1200 S. And the Endurance was the HP2 Enduro, a kind of stripped-down R 1200 GS.)

In that year, BMW came sixth in the manufacturer titles. Ducati won. Kawasaki, who came seventh, went on later to win for many years with their revamped ZX-10R.

BMW just wanted to play in 2009, but in subsequent years, they haver had a factory win, though they came close in 2012 by coming second. At the end of the 2013 season, they terminated their factory involvement, saying they wanted to focus on consumer bikes.

If you look at the BMW S 1000 RR and compare it to most other superbikes you may think it’s just another 1000cc inline four-cylinder engine in a sportbike chassis with USD forks and so on.

All the other manufacturers’ production literbikes peaked in power before 12,500 rpm, whereas BMW peaked at 13000 (or a shade over, per the dyno). BMW got to these high RPM figures with a high-speed, extra-sturdy valve drive with individual cam followers and titanium valves.

Akrapovič, the exhaust manufacturer, did its own apples-to-Äpfel dyno comparison. The order is very slightly different, but BMW is still on top in both metrics.

More importantly, the S 1000 RR’s broad torque curve became a well-loved feature — something BMW learned, no doubt, partly from studying the K5 GSX-R1000’s virtues.

The 2009 BMW S 1000 RR was a rare production superbike with optional ABS and Dynamic Traction Control, which is traction control that takes lean angle (and later, cornering acceleration) as an input.

BMW’s system was unique in that it was lightweight, weighing only 2.5 kg / 5.5 lb. Other brands (e.g. Honda with its CBR1000RR) had ABS as an option, but it was less often chosen because of the considerable added weight (up to 10 kg / 22 lb).

Ducati was also very early in 2012 with acceleration-aware traction control from the IMU. Other brands were earlier with cornering ABS, but when BMW made it an option in 2017, it was retrofittable back to 2012, thanks to the advanced hardware.

Not everyone likes it, of course, and BMW ditched it in the 2019 generation. I would be more dismayed if the 2019 gen didn’t look so good. (Pics below in that section!)

The BMW S 1000 RR hasn’t changed fundamentally since its launch. It has always had a 999cc liquid-cooled 16-valve inline four-cylinder engine making north of 140 kW (190 hp).

The DTC on the first-generation BMW S 1000 RR was advanced for the time. Depending on the ride mode you were in, it worked by interrupting power based on the angle at which the bike was leaning.

BMW’s DTC system from 2012 onward takes input from more advanced sensors. The sensor array is good enough that you can retrofit 2012+ models with “ABS Pro”, BMW’s name for cornering ABS, when it became an option from 2017, via enabling codes (see this guide, which discusses the retrofit option).

BMW refined the way DTC worked intervened, allowing more slip in race and slick modes. Slick mode deactivates wheelie control altogether in the 2012 model, whereas in the first gen, slick mode let you do wheelies of up to five seconds.

The second gen still had an asymmetrical headlight design and the analogue tachometer. But BMW improved the display for better legibility of the speed display, also letting you dim it, and adding more functions like “best lap in progress” or “speed warning” if you need it.

The BMW HP4 is a race-focused bike, released in mid 2012 (see press release) for the 2012-2013 model years. It’s distinct from the BMW HP4 Race which was released in 2017 for that year only (see below).

The HP4 is technically a successor to the boxer-powered HP2 Sport, which in turn had more in common with the boxer sport bike the BMW R 1200 S. But the HP4 is the first four-cylinder HP bike.

The BMW HP4 is heavily based on BMW S 1000 RR. It shares the inline four-cylinder engine, with the same specs on paper, but with tuning to increase midrange torque between 6000 and 9750 rpm. The engine also has the same throttle response and full power output in all ride modes (but other characteristics change, like ABS/traction control).

But the BMW HP4 is much lower weight (199 kg DIN unladen, vs 206.5 kg for the 2012-2014 S 1000 RR, both including ABS), due to lighter 7-spoke forged alloy wheels, a lighter sprocket carrier, a lighter battery, carbon parts, and a lighter titanium exhaust.

The DDC system doesn’t just measure speed and acceleration/ deceleration. It takes input from an IMU that can also feed it information about pitch and lean angle. Because the BMW HP4 has an IMU already, BMW offered in 2014 the ability to retrofit these bikes with cornering ABS (ABS Pro in BMW nomenclature).

BMW also added Race ABS with an enhanced “slick” mode. The internal “IDM” setting configures Race ABS with specific parameters, obtained from experience on the track, to optimise the HP4’s ABS for track use.

In late 2014, BMW announced a new revision for the S 1000 RR for the 2015 model year, with more power again, a slight weight reduction, and a host of technological features, which would be improved upon again slightly in 2017.

But BMW didn’t just improve top-end power; they focused on producing a broad spread of torque from 5000rpm all the way up to 12000 rpm (though not as impressive as the even flatter torque of the 2019+ ShiftCam engine).

BMW added a “Race Package” from 2015, which gave the user DDC (a more advanced version, from the HP4), launch control, a pit limiter, and cruise control.

In 2017, BMW made a small change to the S 1000 RR when they made cornering ABS (which BMW calls ABS Pro) standard. Shortly afterwards, BMW made ABS Pro available as a retrofittable option to earlier models from 2012 onwards. (Many took them up on this as it only cost around 400 Euro/500 USD — check that “ABS Pro” shows up on the dash if you’re buying a used one.)

Finally, I prefer the analogue white-faced tachometer of the Gen 3 S 1000 RR. This is a personal preference. The TFT on the Gen 4 is great looking, but ultimately, it reminds me too much of my phone and of technology — something I’m trying to leave behind when I’m riding (or taking part in any kind of leisure).

The BMW HP4 Race is another race-focused version of the BMW S 1000 RR, an evolution of the BMW HP4 made between 2012-2013. Only 750 were made, all in the year of 2017.

Unique Rider aidsStandard ABS, ABS Pro (optional), Optional quickshifter, Ride modes (street oriented, optional customisable)HP Shift Assistant Pro, DTC (later intervention), EBR(+/-7), 4 customisable ride modes, data loggers, dash with mechanic sideBMW S 1000 RR Gen 3 (2017-2019) vs BMW HP4 Race core differences

The engine itself is hand-crafted by a small team of experts at BMW in Berlin. There are a number of changes that contribute to its increased power and torque:

In case you were wondering, yes, the BMW S 1000 RR in 2019 is both more powerful and lighter — in fact, the weight of the S 1000 RR is the lowest it has ever been. With the M package it’s an absurdly low 193.5 kg.

Aside from power and weight, another marquee features of the 2019+ BMW S 1000 RR is that ShiftCam engine. ShiftCam is BMW’s name for variable valve timing (VVT). The tech means that they alter the valve timing and stroke, allowing the engine to breathe differently depending on its load.

BMW also made chassis improvements in the Gen 4 BMW S 1000 RR. They implemented what they call the Flex Frame, increasing the load-bearing function of the engine, and improving the ergonomics as a result, by

The 2019 BMW S 1000 RR has different brakes to the earlier versions. They’re no longer made by Brembo and are now made by Hayes, an American company (owned by Brembo), apparently chosen after blind testing. The rear caliper is still made by Brembo.

Note — BMW recalled the Hayes calipers S 1000 RR. The calipers may leak when parked. It’s slowly and doesn’t cause the brakes to fail, but riders would notice fluid marks on the rim, tire, or ground. As part of the recall, the caliper would be replaced by the same Nissin caliper that came standard in the 2021+ models.

BMW also changed the analogue tach + LCD to a full-colour TFT display. While it looks cool and clean, I will miss the white dial. (Am I already old? Perhaps I’ve just dropped too many a phone and see all screens as fragile… in reality, I’ve also had CAN bus bikes fail to start when an analogue tacho was broken.)

From late 2020, the latest BMW S 1000 RR has also been available with the M Endurance chain, a low-maintenance chain with a very hard diamond-like coating on the rollers. See more about the M Endurance chain here.

Anyone familiar with motorsports would be familiar with the iconic M range from cars — the BMW M3, M5 and so on. Well, 2021 is the first year that the M range has included motorcycles. Remember this and tell your (or someone else’s unwitting) grandkids!

The 5th gen BMW S 1000 RR has the same ShiftCam engine as in the 4th gen BMW S 1000 RR, but BMW has implemented a few things from the M 1000 RR (which came after the 4th gen), including

BMW added a new tech feature of “Slide control” to the 5th gen S 1000 RR. Just in case you didn’t feel like enough of a superhero with the IMU that the S1KR has had since the 3rd gen, BMW added a steering angle sensor to help control how you power slide!

Here’s how slide control works. The BMW IMU / ECU interprets measures slip angle and compares it with the set value per the DTC settings. If the computer thinks you might go past maximum slip, the slide control system moderates the amount of drive to limit slip.

Improve Shift Assistant Pro. BMW improved the quickshifter, implementing your shift request via a “torque model” and thus letting you use it in all situations. They also improved the mechanism. It’s now easier to change to race shifting, too.

BMW also refined the chassis geometry, flattening the steering head by 0.5 degrees to 66.4 degrees rather than 66.9, and reducing the offset of the triple clamps by 3 mm. The goal of this, and a few other changes, is to subtly improve riding position and feedback from the front wheel.

Yamaha YZF-R1 “Crossplane”. Yamaha has been making its crossplane crankshaft-equipped R1 since 2009 too, coincidentally. The 2015 version was built for even more power, and got a six-axis IMU with cornering ABS, two years ahead of the S 1000 RR (which got it in 2017, retrofittable to 2015). You’d pick the R1 for that unique engine and sound and for even wider service intervals (40000 km +). The R1 never got heated grips or cruise control.

Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade. Since the first 2004 CBR1000RR, Honda has always been a bit lower on the power and features than its competitors, only getting an IMU as of the 2017 model year for example. You’d pick the Honda if you’re after legendary Honda reliability or if you’re tickled by the history of the Honda FireBlade. But otherwise it stacks up comparably with the S 1000 RR on power and torque delivery, and the BMW outclasses it in tech and functions. As of 2021 though, the CBR1000RR-R SP is a very expensive and exclusive bike.

Aprilia RSV4, RSV4 R, RSV4 Factory, RSV4 R APRC, RSV4 RR. You’d buy an Aprilia RSV4 if you want a V4 engine. It’s an incredible machine. You give up a bit in terms of comfort — it’s smaller, with a more aggressive position. In recent years the 1100cc RSV4 has been more powerful AND lighter than the BMW S 1000 RR. Cornering ABS and cruise control since 2017.

Suzuki GSX-R1000. Another iconic sportbike — recall that the 2005 model was a primary inspiration for the first S 1000 RR. The latest 2017+ Gixxer is comparable in power (150 kW/202 hp) and weight (201 kg/443 lb) with the latest S 1000 RR. The 2017+ Suzuki superbike has quite an advanced engine too, with variable valve timing equipped. But the latest standard Gixxer lacks cornering ABS (despite having an IMU for traction control), uses a full monochromatic LCD rather than TFT, and doesn’t come with even a shock quickshifter. The higher-spec R model does have cornering ABS, bi-directional quick shifter, but not fancy features like cruise control or heated grips.

Spec2017-2018 BMW S 1000 RR2017-2018 BMW S 1000 R2017-2020 BMW S 1000 XRPower145 kW (199 hp) @ 13,500 rpm121 kW (165 hp) @ 11000 rpm121 kW (165 hp) @ 11000 rpm

If you’re buying a used BMW anything, make sure you buy one with a complete maintenance log. BMW buyers can be quite fussy and expect the log to be complete.

If it’s the former, it’s resolvable, and BMW may do it themselves on their coin. But if it’s a problem with the camshaft, it’s higher risk, and there are some stories of engine failures. If the top-end is noisy and the previous owner hasn’t resolved it, it would be safer to walk away, unless you’re confident you can resolve it yourself..

The United States filed two amicus briefs in this case, brought by private plaintiffs. They had claimed that a condominium complex in Anne Arundel County, Maryland violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to be designed and constructed so that it is accessible and usable by persons with disabilities. In the United States" first brief, the Division set forth the standard for determining whether the defendants had violated the accessibility provisions of the Act. In the second brief, which was filed on December 20, 1999, the Division presented the court with our views as to what equitable remedies are appropriate in a case in which the defendants have been found liable for violating the accessibility provisions of the Fair Housing Act. On April 21, 2000, the court granted the plaintiffs" request for both monetary damages and equitable relief. In its opinion, the court found that "affirmative action relief in the form of retrofitting or a retrofitting fund is an appropriate remedy in this case." Accordingly, the court ordered the establishment of a fund of approximately $333,000 to pay for the cost of retrofitting the common areas of the condominium and, with the consent of individual owners, interiors of inaccessible units. Individuals seeking to retrofit their units will be entitled to receive an incentive payment of $3,000 to do so. Although the condominium association was not found liable for the violations, the court ordered it to permit the retrofitting of the common areas. The court will also appoint a special master to oversee the retrofitting project, and retains jurisdiction until all funds have been expended or distributed. If any funds remain unspent, the court noted that "the equitable principles and the purposes" of the Fair Housing will guide the distribution of those funds.

On June 28, 2000, the United States signed a settlement agreement with a real estate company settling our allegations that one of its former agents violated the Fair Housing Act on the basis of race by engaging in a pattern or practice of discrimination in the sale of a dwelling. The settlement agreement obligates the real estate company, First Boston Real Estate, to implement a non-discriminatory policy, which will be displayed in its offices and distributed to any persons who inquire about the availability of any properties, as well as to all agents. There are reporting requirements and the Metropolitan Fair Housing Council of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma will receive $3,000.00 in compensatory damages.

On November 29, 2001, the United States entered into a settlement agreement with Jubilee Apartments, Inc.; Falcon Development Company; and J. Lamont Langworthy (respondents) to settle alleged violations of Section 804(f)(3)(C) of the Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3604(f)(3)(C) with respect to the design and construction of the apartments at Palermo Apartments, formerly known as Jubilee Apartments. The case was referred to the United States by HUD on January 27, 2000. The settlement requires the respondents to retrofit the public use and common areas, post a nondiscrimination policy, provide staff training on the Fair Housing Act and submit periodic reports to the United States.

On February 15, 2007, the court entered a consent decree resolving Memphis Center for Independent Living and United States v. Grant(W.D. Tenn.). The United States" complaint, which was filed on November 6, 2001, joined a case filed on January 25, 2001, by the Memphis Center for Independent Living ("MCIL"), a disability rights organization, alleging that the defendants failed to design and construct the Wyndham Apartments in Memphis and Camden Grove Apartments in Cordova, Tennessee, with required features for people with disabilities. The consent decree requires the Richard and Milton Grant Company, its principals and affiliated entities, and their architects and engineers, to retrofit apartments and public and common use areas at the two complexes, and to provide accessible pedestrian routes from front entrances of ground floor units to public streets and on-site amenities. The defendants must establish a Community Retrofit Fund of $320,000, administered by the MCIL, to enable qualified individuals in Shelby County, Tennessee, to modify residential dwellings to increase their accessibility to persons with disabilities. The defendants also are required to pay $10,000 in compensatory damages to the MCIL and $110,000 in civil penalties to the government, and to undergo training on the requirements of the Fair Housing Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The consent decree will remain in effect for three years.

On February 11, 2008, the United States filed a brief as respondent in Nelson v. HUD(9th Cir.). The brief asserted the HUD correctly interpreted its own regulations to require, upon proof of noncompliance with HUD"s Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines, that petitioners demonstrate compliance with some other objective measure of accessibility. The brief also asserted that Montana Fair Housing has standing under the Act; The ALJ"s initial decision dismissing the suit against the Nelsons is not HUD"s final order, and thus, not reviewable; HUD"s ruling that front entrances must be made accessible correctly interprets the Act; HUD properly held Bernard Nelson liable as a co-owner of the property and that the petitioners are not protected by their holding company from the court"s jurisdiction to enforce the remedial order"s retrofitting requirements. The case was closed on October 6, 2011.

The United States signed a modification agreement with Pulte Home Corporation (Pulte) to supplement and amend a settlement agreement previously entered into with Pulte in July 1998. The 1998 settlement agreement resolved the United States" allegations that Pulte had failed to design and construct certain developments in Florida, Illinois, and Virginia to be accessible to persons with disabilities as required by the Fair Housing Act. The modification agreement covers three additional properties in Las Vegas, Nevada, and includes provisions requiring Pulte to annually notify current owners, for a period of three years, of their option to have Pulte retrofit their units at no expense to them in order to bring them in compliance with the Act, as well as to report to the United States the names and addresses of those persons who elect to have their units retrofitted.

On April 1, 2003, the United States entered into a settlement agreement with the developer, architect, site engineer, and homeowners association of Spanish Gardens Condominiums (respondents) in suburban Las Vegas, Nevada. As reflected in the agreement, the respondents failed to design and construct 112 ground-level units and various public and common use areas of the Spanish Gardens Condominiums, a/k/a Desert Lion Condominiums, to be accessible to persons with disabilities. Previous to the signing of the agreement, the respondents had already retrofitted a portion of the common use and public areas at an approximate cost of $35,000. Pursuant to the settlement agreement, the respondents will within 60 days of the Agreement, submit a plan for completion of the remaining required retrofits to the common areas, for approval by the Division. Additionally, the respondents will create an $11,000 fund for use by any homeowner to retrofit the interior of his or her unit. After an initial notice, owners shall receive additional notices of the opportunity to retrofit their units, at no cost to them, on an annual basis for three years. The respondents shall also report information regarding future design or construction of multi-family housing and certify to the Department that such design or construction fully complies with the Act. This matter was referred to the Division by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

On May 25, 2012, the court entered a consent decree in United States v. 475 Ninth Avenue Associates, LLC(S.D.N.Y.), a Fair Housing Act pattern or practice design and construction case alleging discrimination on the basis of disability. The complaint, filed together with the consent decree by the United States Attorney"s Office on May 25, 2012, alleges that the defendants failed to design and construct Hudson Crossing, a 259-unit apartment building in New York City, in compliance with the Fair Housing Act"s accessibility guidelines. The decree provides injunctive relief and requires retrofits of certain noncompliant features in the public and common-use areas and within the dwellings. The decree requires the defendants to pay up to $115,000 to compensate persons aggrieved by the alleged discriminatory housing practices at Hudson Crossing, with unspent monies to be distributed to a qualified organization conducting fair housing enforcement-related activities in New York City. A civil penalty of $20,000 is also imposed.

On May 24, 2017, the court entered a final partial consent decree in United States v. Albanese Organization, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.). The complaint, which was filed on January 18, 2017, against the designers and developers of The Verdesian, an apartment building in New York City, alleged that the defendants violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to design and construct The Verdesian so as to be accessible to persons with disabilities. This fianl consent decree resolves allegations against the architect of the Verdesian, SLCE Architects, LLP. It provides for standard injunctive relief, a payment of $15,000 to compensate aggrieved persons, and a $30,000 civil penalty. A prior partial consent decree, entered on February 13, 2017, resolved allegations against the developers of the property and provided for standard injunctive relief, compliance surveys for two additional properties developed by the defendants, retrofits of non-compliant features, payments of $175,000-$500,000 to aggrieved persons, and a $45,000 civil penalty. The case was litigated by the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York.

On January 25, 2001, the court entered a consent decree inUnited States v. Aldridge & Southerland Builders, Inc. (E.D.N.C.). The complaint, which was filed on January 19, 2001, alleged that a developer and an architect failed to design and construct a 226-unit apartment complex in Greenville, North Carolina, with the features of accessible and adaptable design required by the Fair Housing Act. The violations include steps into the individual units, an insufficient number of curb cuts, doors which are impassable by persons using wheelchairs, no reinforcements in the bathroom walls for the installation of grab bars, and an inaccessible rental office. The consent decree includes the following: the builder and developer, must: (1) retrofit the common use areas of the apartment complex; (2) ensure that at least one fully retrofitted one-bedroom unit and two-bedroom unit remain vacant and available at all times for viewing and rental by a prospective tenant who requests such a unit; (3) give notice to every prospective tenant of the availability of the fully accessible units; (4) compensate aggrieved persons up to $5,000 over any out of pocket costs suffered by such persons; and (5) include enhanced accessibility features in a portion of the units in the next two multi-family projects which they construct. Rivers & Associates, Inc., the architectural firm that designed the complex, must: (1) pay a $5,000 civil penalty; (2) donate 100-hours of technical assistance to non-profit organizations that serve the housing needs of persons with disabilities in the Greenville community; and (3) contribute to any amount paid to compensate aggrieved persons by Aldridge & Southerland.

On October 16, 2019, the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York filed a complaint inUnited States v. Atlantic Development Group, LLC (S.D.N.Y.), alleging a pattern or practice of violations of the accessible design and construction requirements of the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”). Specifically, the United States alleges that Atlantic Development Group and its principal, Peter Fine, have designed and constructed more than 6,000 apartments in 68 rental buildings throughout the Bronx, Manhattan, and Westchester County that do not comply with the FHA’s accessibility requirements. The lawsuit seeks a court order directing the defendants to retrofit these buildings to make them accessible to people with disabilities, to make changes to policies and procedures, and to compensate individuals who suffered discrimination due to the inaccessible conditions.

On October 22, 2002, the court (Lawson, J.) entered the consent decree in United States v. Barrett (M.D. Ga.). The Division"s complaint , filed October 9, 2002, alleged that John Barrett, an Athens, Georgia apartment-complex owner and developer, violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to construct accessible housing in seven apartment complexes which he owns and operates. In addition to Mr. Barrett, the complaint named several companies with which he is associated as defendants in the lawsuit. Three of the apartment complexes are located in Athens, Georgia; two are located in Statesboro, Georgia; and one is located in Greenville, North Carolina. By signing the decree, the defendants admitted their failure to design and construct the subject properties in compliance with the requirements of the Fair Housing Act. The consent decree requires Mr. Barrett and his companies over the next 15 months over the next 15 months to retrofit the public and common use areas of the seven complexes and of the individual apartments units to make them accessible to persons with disabilities. Among the features which will be retrofitted are bedroom and bathroom doors which are too narrow to accommodate persons who use wheelchairs; clear floor space in bathrooms that is inadequate for use by persons in wheelchairs; and excessive sloping of the pavement leading up to dwelling unit entrances as well as the thresholds to those entrances which makes it difficult for persons who use wheelchairs to enter units. The estimated cost of the retrofits is approximately $800,000. In the event that any current residents have to be relocated during the term of their tenancy or that any prospective residents have their move-in dates delayed because of the retrofits, the decree provides for the payment of reasonable relocation or housing expenses and $750 in the event of any such relocation or delay. The decree also requires the defendants to pay $15,000 in civil penalties and contributions to a fund to further housing opportunities for persons with disabilities.

On March 15, 2019, the United States Attorney’s Office entered into a settlement agreement to resolve United States v. Bedford Development (S.D.N.Y.), a Fair Housing Act election and pattern or practice case. The complaint, filed on March 1, 2017, and amended on March 6, 2017, alleged that the defendants Robert Pascucci, Bedford Development, LLC, Carnegie Construction Corp., Jobco, Inc., and Warshauer Mellusi Warshauer Architects P.C. violated the Fair Housing Act on the basis of disability by failing to design and construct the Sutton Manor condominium building in Mount Kisco, New York with the accessibility features required by the Act. The settlement agreement requires the defendants to pay for up to $172,784 for retrofits to common areas and units, establish an aggrieved persons fund of $30,000, pay $322,216 for damages, attorneys’ fees, and unit retrofits to the private plaintiffs who filed the HUD complaints that initiated the matter, report future design and construction projects to counsel for the United States, and agree to refrain from discrimination based on disability in the future.

On July 23, 2015, the United States filed a consent order in United States v. Biafora"s Inc.(N.D. W. Va.). The pattern or practice complaint, filed on September 29, 2014, alleged that Biafora"s Inc. and several affiliated companies violated the Fair Housing Act and the ADA when they designed and constructed twenty-three residential properties in West Virginia and Pennsylvania with steps, insufficient maneuvering space, excessive slopes, and other barriers for persons with disabilities. The consent order requires the defendants to pay $180,000 to establish a settlement fund, and a $25,000 civil penalty, as well as to make substantial retrofits, including replacing excessively sloped portions of sidewalks, installing properly sloped curb walkways to allow persons with disabilities to access units from sidewalks and parking areas, replacing cabinets in bathrooms and kitchens to provide sufficient room for wheelchair users, widening doorways and reducing door threshold heights. The settlement also requires the defendants to construct a new apartment complex in Morgantown, West Virginia, with 100 accessible units. The court entered the consent order on July 24, 2015.

On February 14, 2001, the court entered a consent decree in United States v. Bigelow, Inc. (N.D. Ill.). The complaint, which was filed on April 13, 2000, alleged that the Bigelow Group, the developer of a 286-unit housing development, violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to design and construct the development so that they are accessible and usable by persons with disabilities. Specifically, the complaint alleged that there are excessive slopes in the public areas, as well as steps leading to some of the units, some doors are too narrow for the passage of wheelchairs, and the kitchens and bathrooms are not readily usable by persons who use wheelchairs. The consent decree requires the defendant to offer current residents the opportunity to have their units retrofitted at no expense to them and to make a similar offer annually to each resident for the next three years. In addition, the decree requires the defendant and its employees to make future housing accessible to persons with disabilities, to receive fair housing training, to advertise to the public that their units are accessible to persons with disabilities, and to notify the Civil Rights Division of other covered multi-family dwellings it designs and constructs and provide a certification by the architect that it complies with the accessibility requirements of the Fair Housing Act. The case was based on evidence generated by the Division"s Fair Housing Testing Program.

On November 20, 2003, the court entered a complaint and consent decreeresolving United States v. Black Wolf, Inc. (The Mounty) (N.D. W. Va.). The public accommodations complaint alleges The Mounty, a bar and restaurant located in Chester, West Virginia, discriminated on the basis race and color when it refused to serve African-Americans, in violation of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The complaint alleges The Mounty required African-Americans to display a "membership card" before being served while not demanding the same from non-African-American persons. Under the terms of the consent decree, The Mounty agrees to: train its employees in the requirements of Title II; post a sign at all entrances stating that it does not discriminate against customers on the basis of race or color; include similar announcements in all advertisements; and file periodic reports with the Division regarding its compliance with the agreement. The consent decree will remain in effect for three years. The complaint was initially referred to the Division by a citizen and investigated by the Division"s Fair Housing Testing Program.

On January 6, 2003, the United States submitted a consent decree to the Magistrate Judge in United States v. Bleakley(D. Kan.), a case alleging that the developer, architect and the civil engineer involved in building two apartment complexes in Olathe, Kansas had violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to make the complex accessible to persons with disabilities. Under the consent decree, the defendants will spend more than $350,000 to retrofit the complexes in order to make them accessible, establish a $214,443 fund that will be available to make accessibility modifications to other housing in the community, pay $130,000 to a fund for the compensation of persons with disabilities who experienced difficulty living at or visiting the inaccessible apartment complexes, and pay a $20,000 civil penalty. The total payment of the settlement will therefore exceed $715,000. The architect and the civil engineer defendants are also defendants in United States v. LNL Associates/Architects, et al., which involves similar issues at two other apartment complexes in Olathe, Kansas, and is still pending. In its complaint, filed on May 10, 2001, the Division alleged that the defendants failed to design and construct 340 covered units at the Homestead Apartment Homes, and 160 covered units at the Wyncroft Apartments, so that they would be accessible and usable by people with disabilities in accordance with the federal Fair Housing Act. The Division alleged the violations of the accessibility provisions included: doors that are not wide enough for wheelchairs to pass through; kitchens and bathrooms with insufficient space to allow those in wheelchairs to maneuver and use the appliances, sinks, toilets, and bathtubs; failure to provide accessible routes that allow people using wheelchairs to get into and move around apartments and public and common use areas that required persons to go up with steps or travel steeply-sloped sidewalks. The Division also alleged that the rental offices in both offices were inaccessible in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The consent decree was entered by the court on January 29, 2003, and will remain in effect for five years and nine months. The case was referred to the Division after the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) received a complaint from Legal Aid of Western Missouri, conducted an investigation, and issued a charge of discrimination.

On February 18, 2004, the court entered a consent order resolving United States v. Blueberry Hill Associates, L.P.(W.D.N.Y.), a Fair Housing Act pattern or practice case alleging discrimination of the basis of disability. The complaint, filed on October 23, 2002, alleged that the defendants, Blueberry Hill Associates, L.P., Costich Engineering, and Passero Associates, P.C., failed to design and construct Blueberry Hill Apartments in Rochester, New York, in accordance with the accessibility guidelines provisions of the Act. Under the consent order, the defendants will retrofit the complex, including the interiors of all 168 ground-floor units as well as sidewalks, entryways, and other public exterior spaces to bring it into compliance with the Fair Housing Act. The defendants will also pay $300,000 to compensate individuals who experienced difficulties living at the complex, or who were unable to live in the complex, due to its non-compliance and a $3,000 civil penalty to the United States. The consent decree will remain in effect for five years. The case was referred to the Division by HUD after it received a complaint from a tenant with a disability, conducted an investigation, and issued a charge of discrimination.

On February 22, 2018, the United States filed a complaint and entered into a settlement agreement inUnited States v. BMW Financial Services (D. N.J.), a Servicemembers Civil Relief Act pattern or practice case that alleges failure to refund pre-paid lease amounts to servicemembers who terminated their motor vehicle leases early after receiving military orders.The settlement agreement requires BMW FS to pay $2,165,518.84 to 492 servicemembers and $60,788 to the United States Treasury. The agreement also includes non-monetary relief, including changes in BMW FS’s lease termination policies to ensure that required refunds are provided, and employee training.

On October 6, 2004, the court entered a consent decree resolving United States v. Bray (C.D. Ill.). The complaint, filed on December 18, 2002, alleged that the defendants, the developer/owner/manager and the architect of the John Randolph Atrium Apartments in Champaign, Illinois, violated the Fair Housing Act by failing to design and construct nine ground-floor units and the public and common use areas in the complex in compliance with the accessibility requirements of the Act. The consent decree requires the defendants to: undertake substantial retrofits; estimated to cost over $175,000; pay $10,000 to the complainant in compensatory damages, and to establish a $10,000 victim fund. The consent decree will remain in effect for two years. The case was referred to the Division after the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) received a complaint, conducted an investigation, and issued a charge of discrimination.

On September 14, 2020, the court entered a consent orderin United States v. PR III/Broadstone Blake Street, LLC, et al. resolving a Fair Housing Act design and construction case resulting from an election referral from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The complaint, which was filed on September 26, 2019, alleged that the developer and builder defendants failed to construct The Battery on Blake Street, a rental apartment building in Denver, CO, so that it was accessible to persons with disabilities. The consent order requires certain retrofits to units and common areas in the building in addition to reporting and training requirements and a payment of $5,000 to the HUD Complainant, the Denver Metro Fair Housing Center. The case was referred to the Division after the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) received a complaint, conducted an investigation, and issued a charge of discrimination.

On April 19, 2016, the court entered a supplemental consent order in United States v. Bryan Company (Bryan II) (S.D. Miss.). The complaint, filed on April 19, 2011, alleged the defendants failed to design and construct nine multifamily properties in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee in compliance with the Fair Housing Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. On May 15, 2013, the court entered a partial consent order with the nine architects and civil engineers. The partial consent order required the defendants to pay a total of $865,000 to make the complexes accessible and pay $60,000 to compensate aggrieved persons harmed by the inaccessible housing. The second partial consent order, entered on February 24, 2014, required the developer, builder, and original owner defendants to complete retrofits at each property to bring them into compliance with the FHA and ADA. Both partial consent orders required the defendants to undergo training on the Fair Housing Act and to provide periodic reports to the government. The supplemental consent order transfers the responsibility for completing the retrofits at two of the nine properti

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey