how to dispose of lcd screen made in china

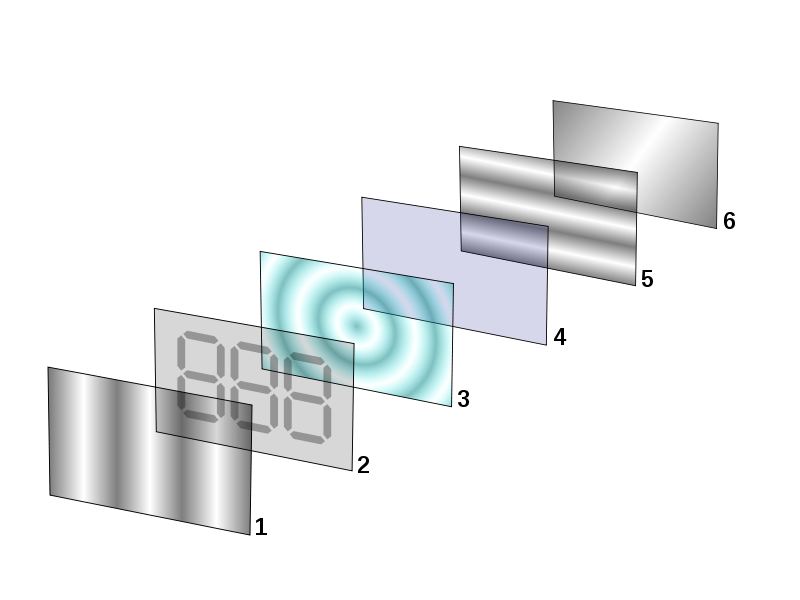

Short-lived electronic devices have become a significant waste stream. This waste is a potential source of valuable metals, but only a small portion is currently recycled. A common electronic waste is the liquid-crystal display (LCD) screen used in computers and televisions. LCDs contain two glass plates sandwiching a liquid-crystal mixture. The outer plate surfaces are covered with polarizer films, but the inner plate surfaces contain a functional indium tin oxide film. Indium is a critical raw material with limited supplies and high costs. Several possible recycling methods have been developed to recover indium but purity remains low.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Guiyu, China, is the last stop for tens of millions of tons of discarded TVs, cell phones, batteries, computer monitors, and other types of electronic waste each year. In this area of Guangdong province in southeast China, the industry is characterized by thousands of small, family-run workshops interspersed with residences, schools, and stores. The workshops employ hundreds of thousands of local and migrant workers to extract copper, silver, gold, platinum, and other materials for resale, often burning or using acid baths to separate out the elements of interest. NIEHS-supported researcher Aimin Chen, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Health at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, is studying the impacts of e-waste recycling on pregnant women and their children in Guiyu.

With an estimated 20–50 million tons of e-waste produced annually worldwide, it is the fastest-growing stream of municipal solid waste. Management of e-waste is a significant environmental health concern. In developing countries, where most informal and primitive e-waste recycling occurs, workers and others who live near these recycling facilities are exposed to dangerous chemicals with potentially long-term adverse health effects. Other locations where such recycling is prevalent include India and Ghana, Liberia, and Nigeria in Africa.

As they process e-waste, workers—who are often children—are directly exposed to lead, cadmium, brominated flame retardants, and other toxic chemicals, many that present development risks. Chen noted that workshops are rarely well-ventilated and workers wear little, if any, personal protective equipment. Individually, these chemicals carry health risks; mixtures of them are potentially further cause for concern. The e-waste that is not commercially viable is dumped or burned. Thus, workers and others in the community, including children, are exposed through inhalation of fumes, ingestion of dust, contact with water and soil, and other pathways.

“As the use of electronics grows in both industrialized and developing economies, this will be an ever-increasing public health problem,” said Chen, with vulnerable populations at greatest risk.

Chen noted the paradox in public perceptions about e-waste recycling: “We often think that recycling is a good thing and better than mining these minerals from the ground,” he said. “The problem comes when the way of recycling is not environmentally friendly or good for people’s health.”

Chen is working in Guiyu with Xia Huo, M.D., Ph.D., a professor and Director of the Analytical Cytology Lab at nearby Shantou University Medical College. The joint study enrolled 600 pregnant women from Guiyu and from a control site. The researchers measured metal exposures in the women, and are looking at birth outcomes and, ultimately, long-term outcomes on the infants’ neurobehavioral development. Chen said they hope to publish the first of their results in the next few months. “We want to analyze exposure levels, and also provide some recommendations about how to advise the community about the risks,” he said.

Huo has conducted her own research on children in Guiyu since 2004. She said she became aware of the potential problems associated with e-waste recycling after joining the faculty at Shantou, about 40 kilometers away from Guiyu, in 1998. A memory of two small children swimming in a highly polluted stream in Guiyu stays with her more than a decade later. In addition to focusing on children because of their developmental issues, studying the workers is also difficult, she said, because they move frequently from workshop to workshop, and even between Guiyu and their homes elsewhere in China. Also, employers are often reluctant to allow researchers to enter their facilities and slow down the work, she said.

Chen’s and Huo’s studies are part of a growing, but still small, body of research on the impacts of e-waste on children. The observed health issues, including respiratory irritation and skin burning, in addition to the effects mentioned above, led the World Health Organization recently to develop an initiative on e-waste and children’s health. In June, with support from NIEHS and others, WHO convened a Work Group on E-Waste and Children to bring together experts and other stakeholders (see Box). An informal survey conducted in preparation for the meeting indicated only a handful of studies exist that look into health impacts of e-waste. One of the objectives of the meeting was to call more attention to the issue among the global scientific and medical communities.

There are some small signs that improved awareness and knowledge of the hazards can lead to improvement. For example, Huo said Guiyu local authorities published a decree in 2012 to ban burning e-waste and soaking it in sulfuric acids, and have promised greater supervision and fines for offenses. She also said that 2012 was the second year since 2004 that concentrations of metal, especially lead, decreased in the children studied. (They attribute the other year of decline—2009—to the global financial crisis that resulted in smaller volume of materials recycled.) Still, much remains to be done in Guiyu and worldwide. Increased awareness of this issue among global consumers, evidence-based interventions, and policy changes will be important to reduce the burden of disease among children and adults working in the e-waste recycling trade.

At the Working Group on E-Waste and Children’s Health meeting convened by WHO in June and co-sponsored by NIEHS and Germany’s Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, NIEHS Director Linda Birnbaum, Ph.D., stressed the importance of understanding and mitigating against the effects of e-waste recycling.

“Having this group review the current situation of e-waste exposure in children, identify research gaps, and highlight successful interventions and strategies will help us determine our next steps,” she said in opening remarks to the participants via a prerecorded video. “E-waste and the impact that it can have on health is a major topic of concern for all of you and for us at NIEHS, especially the impact it has on pregnant women and young children living so close to e-waste recycling sites.”

Chen and Huo were among the approximately 60 experts and other key stakeholders from WHO, other UN agencies, and research institutions. Next steps include creation of a network of researchers willing to share data and disseminate findings, dedicated sessions on e-waste at the Pacific Basin Consortium Meeting and the Fourth WHO International Conference on Children’s Environmental Health, and several publications. In addition, NIEHS will develop a white paper that connects the discussions and recommendations of the meeting as they relate to the mission of the Institute.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

You can return unwanted electronics to manufacturers for recycling or disposal for free. Electronic manufacturers, such as Samsung, Sony, or Toshiba, must accept electronics from residents at no cost. Cell phones can also be dropped off at any store that sells service plans.

You can find more information about recycling electronics at the store where you purchased the item or at any store that sells the item. You can also call the manufacturer or check your brand"s website.

The NY State Department of Environmental Conservation keeps a list of registered electronics manufacturers and information about their e-waste acceptance programs on its website.

Researchers in China may have discovered a workable process for recovering the rare metal indium from liquid crystal displays (LCDs). #indium #recovery #recyclng #electronics #lcd

The EU has identified 20 critical raw materials, including indium, with economic importance and a high supply risk. Indium is mainly used for the production of LCD screens and is predominantly sourced from Chinese mines. This study, funded by the European Commission1 , details the development of a process to recycle indium from waste LCD panels, where indium is found as indium tin oxide (ITO). The study is one of the first to describe how to recover indium from a leaching solution of waste LCD panels. Developing methods to recover materials from waste equipment is an important way of saving resources and reducing primary production of materials.

The researchers recovered indium from waste LCD panels through cementation: the process by which a solid is created from a solution. The panels were first shredded into small pieces and sieved to remove glass and plastic fragments, then indium was dissolved in a strong acid solution. Zinc metal powder was used in the solution to collect the indium, which becomes solid by reacting with zinc during the cementation process.

The study was undertaken in order to identify the best operating conditions under which to recover indium from a solution that contains other metals; 16 experimental treatments were used to investigate the effect of variations in zinc concentration, pH of the acid solution and the duration of the recovery process. An important goal of the process is to ensure that the maximum possible yield of high-purity indium can be obtained from ITO.

The environmental impact of the indium recovery process was also assessed through life-cycle assessment (LCA). The LCA was undertaken to identify the environmental benefits and impacts of recovering indium using this method, in terms of the loss of (non-living) natural resources and global-warming impacts. Indium recovery from waste LCD panels was compared with incineration and use of landfills, which are the current methods of LCD waste disposal.

The highest indium recovery (99.8%) using an acid solution with a pH of 2 was achieved when a relatively high concentration of zinc was used (100 grams per litre, g/L). Overall, the best results for indium recovery were found using a solution with an acidity of pH 3, which led to high recovery of indium even at low concentrations (5 g/L) of zinc. The percentages of indium recovery at pH 3 were: 98.0% with a low concentration of zinc (2–5 g/L), from 95.0% to 98.9% with a medium concentration of zinc (15–20 g/L) and 99.9% with a high concentration of zinc (100 g/L).

Although the highest recovery rates were achieved using the highest concentrations of zinc, carrying out indium cementation with less zinc is more resource-efficient.

In order to gain indium in its purest possible form it was necessary to allow cementation for 10 minutes. A longer cementation time resulted in an increase of impurities, including aluminium, calcium and iron, relative to the indium. Statistical analysis confirmed that a higher pH, a longer recovery process and higher concentrations of zinc all had a positive impact on the efficiency of the recovery process, but longer recovery times increased the level of impurities in the recovered product.

The LCA indicated that, in general, indium recovery from waste LCDs has environmental benefits when compared to landfill or incineration options. Incineration had the highest costs in terms of global-warming impacts. Indium recovery also had a net environmental benefit in relation to natural resource depletion.

The study demonstrates a method to recycle indium from end-of-life LCDs rather than mining from natural reserves, which will be valuable for industries and researchers working in critical raw materials recovery. The study also supports the development of effective strategies for the recovery of secondary indium in Europe (relevant to the EU Directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment2), with resulting benefits of decreasing dependency on imports from other countries.

Matharu AS, Wu Y (2008) Liquid crystal displays: from devices to recycling. In: Hester RE, Harrison RM (eds) Electronic waste management, issues in environmental science and technology. RSC Publishing, Cambridge UK

Directive 2002/96/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) – Joint declaration of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission relating to Article 9; http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Yuan Z, Shi L (2009) Improving enterprise competitive advantage with industrial symbiosis: case study of a smeltery in China. J Cleaner Prod 17:1295–1302

Eugster M, Huabo D, Jinhui L, Perera PJ, Yang W (2008) Sustainable electronics and electrical equipment for China and the world – a commodity chain sustainability analysis of key Chinese EEE product chains. International Institute for Sustainable Development, pp 1–91

Schluepa M, Hageluekenb C, Kuehrc R, Magalinic F, Maurerc C, Meskersb C, Muellera E, Wang F (2009) Sustainable innovation and technology transfer industrial sector studies: recycling from E-waste to resources. United Nations Environment Programme and United Nations University, Nairobi, Kenya

E-Waste Volume 1 Inventory Assessment Manual (2007) United nations environmental programme division of technology. Industry and Economics International Environmental Technology Centre, Osaka/Shiga

Ongondo FO, Williams ID, Cherrett TJ (2010) How are WEEE doing? A global review of the management of electrical and electronic wastes. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2010.10.023

Waste and Climate Change. Global Trends and Strategy Framework (2010) United Nations Environmental Programme, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics International Environmental Technology Centre, Osaka/Shiga, pp 1–79

Boggio B, Wheelock C (2009) Executive summary: electronics recycling and E-Waste issues recycling and responsible disposal of consumer electronics, computer equipment, mobile phones, and other E-Waste. Pike Research LLC, Boulder, USA

Chancerel P, Meskers CEM, Hagelűken C, Rotter VS (2009) Assessment of precious metal flows during preprocessing of waste electrical and electronic equipment. J Ind Ecol 13(5):791–810

Directive 2002/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment; http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of HazardousWastes and Their Disposal; http://www.basel.int/text/con-e-rev.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC; http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/reach/reach_intro.htm. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Directive 2005/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2005). Official Journal of the European Union: L191/29-L191/58. http://www.energy.eu/directives/l_19120050722en00290058.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Martin R, Simon-Hettich B, Becker W (2004) New EU Legislation (WEEE) Compliant Recovery Processes for LCDs. IDW 04 Proc of the 11th IDW: 583-586. http://www.lcdtvassociation.org/images/Proceeding_New_EU_Legislation_WEEE_Compliant_Recovery_Processes_for_LCDs-Merck_September_2008n.pdf. Accessed 6 Feb 2011

Lo S-F (2010) Global warming action of Taiwan’s semiconductor/TFT-LCD industries: how does voluntary agreement work in the IT industry? Technol Soc 32(3):249–254

Lei C-N, Whang L-M, Chen P-C (2010) Biological treatment of thin-film transistor liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) wastewater using aerobic and anoxic/oxic sequencing batch reactors. Chemosphere 81:57–64

You S-H, Tsai Y-T (2010) Using intermittent ozonation to remove fouling of ultrafiltration membrane in effluent recovery during TFT-LCD manufacturing. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 41:98–104

Kim Y-J, Qureshi TI (2006) Recycling of calcium fluoride sludge as additive in the solidification-stabilization of fly ash. J Environ Eng Sci 5(5):377–381

Lin K-L, Chang W-K, Chang T-C, Lee C-W, Lin C-H (2009) Recycling thin film transistor liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) waste glass produced as glass-ceramics. J Cleaner Prod 17:1499–1503

Wang HY (2011) The effect of the proportion of thin film transistor-liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) optical waste glass as a partial substitute for cement in cement mortar. Constr Build Mater 25:791–797

Nakamichi M Jpn. Kokai. Tokkyo Koho JP 2005 227,508 (Cl. GO2F1/13), 25 Aug 2005, Appl. 2004/35,597, 12 Feb 2004. Decomposition method and apparatus for liquid crystals in recycling of liquid crystal panels. CAN: 143: 219606g

Felix J, Letcher W, Tunell H, Ranerup K, Retegan T, Lundholm G (2010) Recycling and re-Use of LCD components and materials. SID Symp Dig Tech Pap 41(1):1469–1472

It is believed that much of the waste is imported from developed countries. The European Union has sanctions against exporting waste to developing countries, but those rules are aggressively ignored. Many waste goods are classed as "charitable donations" before they"re dumped on scrap heaps. Similarly, Agbogbloshie, in Ghana, is another example how thousands of tons of electronic waste from Europe is dumped in developing countries.

Once a rice village,recycling operations in Guiyu are toxic and dangerous to workers" health with 80% of children suffering from lead poisoning.miscarriage rates are also reported in the region. Workers use their bare hands to crack open electronics to strip away any parts that can be reused—including chips and valuable metals, such as gold, silver, etc. Workers also "cook" circuit boards to remove chips and solders, burn wires and other plastics to liberate metals such as copper; use highly corrosive and dangerous acid baths along the riverbanks to extract gold from the microchips; and sweep printer toner out of cartridges. Children are exposed to the dioxin-laden ash as the smoke billows around Guiyu, and finally settles on the area. The soil surrounding these factories has been saturated with lead, chromium, tin, and other heavy metals.groundwater, making the water undrinkable to the extent that water must be trucked in from elsewhere. Lead levels in the river sediment are double European safety levels, according to the Basel Action Network.Chendian.plastic waste sit on the ground beside rice paddies and dikes holding in the Lianjiang River.

Children under the age of 6 are especially vulnerable to lead poisoning, which can severely affect their mental and physical development or even be fatal. Lead can result in irreversible brain damage to their still developing brains. Some symptoms of lead poisoning in children include loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, stomach pain, vomiting, constipation and learning difficulties. Symptoms in adults include high blood pressure, decline in mental functioning, pain/numbness of extremities, muscle weakness, headache, stomach pain, memory loss, mood disorders and fertility problems including higher probability of miscarriages.

The economic incentives created by strict domestic regulation, non-existent or unenforced regulations in developing countries, and the ease of free trade brought about by globalization, led recyclers to export e-waste. The value of parts in discarded electronics provides an incentive for poverty-stricken citizens to migrate to Guiyu from other provinces to work in processing it. Guiyu has 5,500 businesses, many of them family workshops, that dismantle old electronics to extract lead, gold, copper and other valuable metals. This industry employs tens of thousands of people and dismantles 1.5 million pounds of discarded computers, cell phones and other electronics each year. The average worker, adult or child, makes barely $1.50/day (or 17 cents/hour).

Guiyu as an e-waste hub was first documented fully in December 2001 by the Basel Action Network, a non-profit organization which combats the practice of toxic waste export to developing countries in their report and documentary film entitled Exporting Harm.Greenpeace and the United Nations Environment Programme and the Basel Convention. Media documentation of Guiyu is tightly regulated by the Chinese government, for fear of exposure or legal action.60 Minutes TV crew.e-waste recycling in Guiyu using different methods to raise awareness such as building a statue using e-waste collected from a site in Guiyu, or delivering a truckload of e-waste dumped in Guiyu back to Hewlett Packard headquarters. Greenpeace has been lobbying large consumer electronics companies to stop using toxic substances in their products, with varying degrees of effectiveness.

In 2005 a Planet Funk video for their song "Stop Me", shows the situation throughout the city, with people living and working inside an e-waste environment.

Since 2007, conditions in Guiyu have changed little despite the efforts of the central government to crack down and enforce the long-standing e-waste import ban. However, because of the work of activist groups and increasing awareness of the situation, the local government has created steps to improve environmental conditions. "It can be done. Look at what happened with lead acid batteries. We discovered they were hazardous, new legislation enforced new ways of dealing with the batteries which led to an infrastructure being created. The key was making it easy for people and companies to participate. It took years to build. E-waste is going the same route. But attitudes have changed and we will get there", says Robert Houghton, president and founder of Redemtech, an asset management and recovery firm.Guiyu Township government has published a decree to ban burning electronics in fires and soaking them in sulfuric acid, and promises supervision and fines for violations. Over 800 coal-burning furnaces have been destroyed because of this ordinance, and most notably, air quality has returned to Level II, now technically acceptable for habitation.

In 2013, 《汕头市贵屿地区电子废物污染综合整治方案》(Comprehensive Scheme of Resolving Electronic Waste Pollution of Guiyu region of Shantou City) was approved by Guangdong Province government.industrial ecology park where the wastes can be properly treated and recycled.

But not Jim Puckett. His eyes are fixed on the glowing screen of his laptop. Little orange markers dot a satellite image. He squints at the pixelated terrain trying to make out telltale signs.

Dead electronics make up the world’s fastest-growing source of waste. The United States produces more e-waste than any country in the world. Electronics contain toxic materials like lead and mercury, which can harm the environment and people. Americans send about 50,000 dump trucks worth of electronics to recyclers each year.

Puckett’s organization partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to put 200 geolocating tracking devices inside old computers, TVs and printers. They dropped them off nationwide at donation centers, recyclers and electronic take-back programs — enterprises that advertise themselves as “green,” “sustainable,” “earth friendly” and “environmentally responsible.”

“The trackers are like miniature cell phones,” he said. “The little devices went out and spoke to us, called home regularly, saying ‘this is where I am.’”

About a third of the tracked electronics went overseas — some as far as 12,000 miles. That includes six of the 14 tracker-equipped electronics that Puckett’s group dropped off to be recycled in Washington and Oregon.

The tracked electronics ended up in Mexico, Taiwan, China, Pakistan, Thailand, Dominican Republic, Canada and Kenya. Most often, they traveled across the Pacific to rural Hong Kong.

The next morning Puckett follows the little orange markers to a region of Hong Kong called the New Territories, a long-time agricultural area along the border with mainland China that’s shifted toward industry in recent decades.

He teams up with a Chinese journalist and translator, Dongxia Su, and a local driver, who will help navigate the region. They follow a set of GPS coordinates for one of the tracked electronics. Paved streets become rutted dirt roads. They pass a steady stream of trucks carrying shipping containers from the port.

As they approach their first destination — “One-hundred feet away. Eighty feet. Seventy-seven feet,” Puckett says — they hear sounds of power drills and shattering glass. It’s coming from the other side of a high metal wall made from old shipping containers.

A worker shouts from beyond the fence and Su tells him the group is shopping for used electronics. She says they want to fill a shipping container with printers to refurbish and sell in Pakistan. The door opens.

Inside, workers are dismantling LCD TVs. The ground at their feet is littered with broken white tubes. These fluorescent lamps were made to light up flat-screens. When they break they release invisible mercury vapor. Even a minuscule amount of mercury can be a neurotoxin.

The New Territories used to serve only as a pass-through for smuggled e-waste, Puckett said, where workers would unload shipping containers and put electronics on smaller trucks bound for mainland China.

But a crackdown by the Chinese government on whole electronic imports, part of a border control operation called “Green Fence,” has prevented many electronics from moving across the border.

Puckett has been investigating the afterlife of consumer electronics for nearly two decades. Over the years, his team staked out U.S. recycling operations and followed shipping containers overseas to uncover the environmental and human health consequences of the global e-waste trade.

In 2002, the Basel Action Network’s Jim Puckett tests the water quality near Guiyu, China, where residents cooked electronics to extract precious metals and dumped the leftovers in a nearby river. Courtesy of the Basel Action Network

Many U.S. consumers got their first glimpse of what happens to their discarded electronics in Puckett’s 2001 film “Exporting Harm: The High-Tech Trashing of Asia.” It captured the crude recycling methods taking place in Guiyu, a cluster of villages in southeastern China that has since become known as the world’s biggest graveyard for America’s electronic junk.

In the video, villagers desoldered circuit boards over coal-fired grills, burned plastic casings off wires to extract copper, and mined gold by soaking computer chips in black pools of hydrochloric acid. Researchers later found the region had some of the highest levels of cancer-causing dioxins in the world due to its e-waste industry.

Puckett’s documentary came out more than a decade after nearly every developed nation on the globe had ratified the Basel Convention, an international treaty to stop developed countries from dumping hazardous waste on poorer nations.

The United States is the only industrialized country in the world that hasn’t ratified the treaty. Its hazardous waste is still getting exported to countries with fewer health and environmental safety laws, according to Puckett’s latest investigation.

Over the years Puckett’s attempts to quantify and draw attention to exported electronic waste has drawn criticism from U.S. recyclers who say the problem has been exaggerated.

“The vast majority of electronics collected for recycling in the U.S. are recycled in the U.S.,” said Eric Harris of the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, a Washington, D.C.-based recycling trade association. “We would really challenge the notion that there’s a mass exodus of equipment that’s leaving in an unprocessed manner.”

Estimates of U.S. e-waste exports vary widely. The United Nations says that between 10 and 40 percent of U.S. e-waste gets exported for dismantling. While the International Trade Commission — through a survey of recyclers — said in 2013 that a mere 0.13 percent of all used electronics collected in the U.S. went abroad for dismantling.

Puckett turned to GPS tracking technology as a new tool to determine just how big the e-waste export problem really might be. He partnered with Carlo Ratti of the Senseable City Lab at MIT to deploy the strategy.

“Tracking is really the first step in order to design a better system,” Ratti said. “One of the surprising things we discovered is how far waste travels. You see this kind of global e-waste flow that actually almost covered the whole planet.”

A pile of printer parts dusted with toners like carbon black, a possible carcinogen known to cause respiratory problems. Photo by Katie Campbell, KCTS9/EarthFix

Puckett’s GPS receiver leads the way to another set of high fences. A sign out front proclaims that it’s farmland. But a look over the fence reveals a lot the size of a football field piled 15 feet high with printers. Workers are breaking them. Their clothes are dusted black with toner ink, a probable carcinogen known to cause respiratory problems.

Su talks to the workers and finds out many are migrants from mainland China, who are residing in Hong Kong without the official documents required for them to legally be there, she says.

“The majority of these workshops tend to operate in a shady manner,” unlicensed and poorly regulated, said Lau, a licensed, second-generation paper and plastics recycler in the region.

Jackson Lau, head of Hong Kong’s recycling business association, said junkyards that import foreign e-waste often dump the components they don’t sell. Photo by Katie Campbell, KCTS9/EarthFix

Electronics are often labeled as raw plastics to get through customs, Lau said, but they’re actually whole devices that the junkyard workers dismantle. They sell the most valuable components to buyers in mainland China, while workers indiscriminately dump the worthless leftovers.

He said a lack of oversight by Hong Kong’s Environmental Protection Department is not only harming workers in the facilities but also the neighboring communities and environment.

Several fires have broken out at junkyards in the past year, including two incidents in March that emitted plumes of toxic black smoke, according to local news reports. Courtesy of Cheung Choi

Several fires have broken out at junkyards in the past year, including two incidents in March that emitted plumes of toxic black smoke, according to local news reports.

Burning e-waste is known to generate dioxins, a family of cancer-causing chemicals that endure for long periods of time in the environment and human body.

“When I was young, I used to drink water directly from the river,” he said through an interpreter. “Now I do not even dare drink water from the well.”

Hong Kong bans the import of hazardous e-waste like cathode ray tubes and flat-screens from the United States and other developed nations, according to Environmental Protection Department spokesperson Heidi Liu.

“On the whole, Hong Kong has been effective in combating hazardous waste shipments,” Liu said, citing 21 instances in the past three years in which cargo loads of e-waste were sent back to the U.S.

Inside a quiet warehouse in the New Territories, Jim Puckett searches for clues in the clutter of electronic waste. Photo by Ken Christensen, KCTS9/EarthFix

Then he finds a clue as to how these materials ended up here. Many boxes bear the logo for Total Reclaim, one of the largest electronics recyclers in the Pacific Northwest with contracts to handle e-waste from the City of Seattle,King County, the University of Washington and the State of Washington.

Total Reclaim scored these big regional recycling contracts in part because it was certified by e-Stewards, a responsible-recycling certification program created by Puckett’s Basel Action Network. Puckett started e-Stewards in 2010 to create a set of ethical and environmentally-friendly industry standards and prevent the export of toxic materials in lieu of federal laws. Total Reclaim was a founding member.

Electronics recyclers with e-Stewards certification can export the raw plastics and metals that come from dismantling electronics. But they adopt a strict no-export policy with regard to whole electronics with hazardous materials still inside. Recyclers can also exported used electronics as long as they’ve been tested and proven to be still functioning.

Last May Puckett’s team dropped two non-working LCD TVs, with tracking devices placed inside, at separate recyclers in Oregon. From there, the tracked electronics traveled to Total Reclaim’s warehouse in south Seattle. Then they went to the Port of Seattle, across the Pacific Ocean to the Port of Hong Kong and ultimately to two junkyards in the New Territories.

Total Reclaim wasn’t the only leading domestic e-waste recycler that collected non-working electronics with tracking devices inside that went overseas, the Basel Action Network concluded through its investigation.

In 2004 Dell created a take-back program called Dell Reconnect. That made it the first major computer manufacturer to ban the export of non-working electronics to developing countries. The computer maker partners with the nonprofit thrift store chain Goodwill Industries, which collects any brand of old computer for free to be refurbished or recycled.

The investigation focused on Dell’s program after whistleblowers drew Puckett’s attention. BAN dropped off 28 tracked electronics at participating Goodwill locations and determined that six of the tracking devices went abroad — to Hong Kong, Taiwan, mainland China and Thailand.

Beth Johnson, head of Dell’s producer responsibility programs, said the company conducts regular audits of Goodwill and vets downstream recycling partners.

A tracking device planted in a computer dropped off at a Dell Reconnect location led Puckett here, an abandoned field strewn with LCD monitors, CRT monitors, camcorders and keyboards. Photo by Ken Christensen, KCTS9/EarthFix

Goodwill’s public relations official declined requests for an interview and instead issued a statementFriday after Puckett briefed officials about the findings of his group’s investigation.

“Goodwill Industries International is committed to understanding new insights into the e-cycling space from the final report,” the statement said, and “encourages Goodwill organizations participating in the Dell Reconnect program to evaluate the continuation of their contracts with Dell” and to take steps to ensure that electronics are responsibly recycled.

In all, BAN’s investigation found that 65 tracked devices went through U.S. recyclers and ended up overseas. The results showed that some of those exported electronics had been dropped off at green-certified recyclers. BAN plans to conduct further investigations before reporting more about these recyclers.

“I’m getting disillusioned by certification programs,” Puckett said. “It is clear that these certifications need to be better enforced and we intend to do just that.”

In a phone interview, co-owner Craig Lorch acknowledged that some of Total Reclaim’s LCD flatscreen monitors have been shipped to Hong Kong, despite the company’s no-export policy.

Both the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the Washington Department of Ecology have launched investigations into whether Total Reclaim violated their state hazardous waste laws.

Oregon regulators have also asked the state Department of Justice to open an investigation into whether Total Reclaim violated consumer protection laws.

Lorch said economic realities forced the company to renege on pledges to recycle all the waste that they collect. In recent years, LCD monitors have become a larger portion of the waste stream, but the flat-screens are expensive and time-consuming to dismantle.

In January, copper fetched half its 2011 price, hitting the lowest level in seven years. Plastics prices have bottomed out, recyclers say. At the height of the market, Total Reclaim sold steel for $300 a ton. The price recently fell to $60 a ton, Lorch said.

Plastics and metals from dismantled electronics await their turn to enter a machine that shreds and sorts them into commodity type. Photo by Ken Christensen, KCTS9/EarthFix

In a bear market for commodities, exporting waste is more profitable than processing it domestically. Recyclers simply fill a shipping container with whole electronics and an e-waste broker arranges for pick up.

Printers, which hold little value, and LCD TVs, which are expensive to recycle because of the tedious dismantling work associated with mercury, make good candidates for export.

“This e-waste recycling business is like the wild, wild west,” said Wendy Neu, a 30-year veteran of the recycling and scrap metal industry. “People are getting paid to recycle these materials through government programs and then are exporting to China and Africa.”

Neu is the CEO of Hugo Neu, a New York-based e-waste recycler and e-Steward, that just months ago decided to shift its business model away from recycling. Now it only refurbishes electronics for resale. Neu, a board member of BAN, said they couldn’t compete with recyclers that spent pennies on the pound to export, while Neu’s company hired workers and paid for the latest advanced recycling technology.

The Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries has opposed versions of those bills, arguing that these types of laws on exports would harm the recycling sector and are unnecessary because the industry is well-regulated by existing federal and state laws.

The country is home to a patchwork of state laws. In half of states, landfilling electronics is legal. Some states, including Washington and Oregon, have paired landfill bans with laws that incentivize local recycling.

The two Northwest states use “producer responsibility” laws similar to those in the European Union. Electronics manufacturers pay a fee to the state on electronics sold locally. The money helps subsidize approved recyclers like Total Reclaim, which recoup money through the program based on the amount of electronics the company collects.

But according to BAN’s tracking data, even audited companies were found to be exporting, including some in Oregon, Washington, California, Michigan and New Jersey. In addition, states don’t have jurisdiction to ban exports.

“There’s definitely not enough perp walks being done,” said John Shegerian, chief executive of Electronics Recycling International, the largest e-waste recycling firm in the country. “We need to step up enforcement to match the certification programs we have.”

About 20,000 new electronic devices will be released to U.S. consumers this year. More than 1.4 billion smartphones will be sold globally, five times the amount sold five years ago.

1. A study by the Hong Kong Baptist University found surface soils in Guiyu had high levels of cancer-causing dioxins. A different study from Shantou University Medical College found high levels of lead in children’s blood in Guiyu. Late last year, the Chinese government ordered thousands of unregulated businesses in Guiyu to move into a newly built industrial park, an effort to clean up the industry.↩

2. Samson Lai, deputy director of the department, said junkyards only need a license if they process e-waste that’s considered chemical waste, which includes only cathode ray tube monitors and batteries in bulk — not LCD flat-screens or printers.↩

3. Many of those government institutions have signed up as “e-Steward Enterprises,” telling the public they only work with the industry’s certified recyclers.↩

4. Some of the Goodwill locations in the Dell Reconnect program dismantle electronics. At the Goodwill locations that don’t dismantle e-waste, Dell transports the waste to other recycling partners. The company declined to disclose those partners.↩

5. The Environmental Protection Agency has a rule that aims to prevent export of CRT monitors, the boxy computer and TV monitors that were have been out of production since flat-screen technology drove them out of the market nearly a decade ago. The law requires U.S. e-waste collectors to notify the EPA and get written approval from the receiving country before exporting these monitors, each of which carries four pounds of lead.↩

6. ISRI says it would support a ban of exports of used electronics for the purpose of landfilling or incineration in other countries, but that the Basel Convention is too sweeping in its requirements.↩

This report first appeared on EarthFix’s website. EarthFix is a public media project of Oregon Public Broadcasting and Boise State Public Radio, Idaho Public Television, KCTS 9 Seattle, KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio, Northwest Public Radio and Television, Southern Oregon Public Television and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Properly recycling electronics conserves natural resources, ensures appropriate handling of toxic materials, provides a more sustainable source of precious metals, and protects human health and the environment.

Manufacturers of certain electronics that are sold in the District must provide opportunities for people in the District to recycle electronic waste generated in the city. DOEE oversees this program.

- The address of Benning Road Transfer Station is 3200 Benning Rd NE. The electronics collection is available every Saturday from 7am - 2pm (except holidays) and the Thursday before the first Saturday of the month from 10 am to 2pm (except holidays). This location is new as of early October 2021.

Find out how to properly dispose of electronics not included in the eCYCLE program with the “What Goes Where” tool on the Zero Waste DC website. Read more >>

For concerns about data security, please see the following best practices for data-bearing electronic equipment. Electronics collectors recommend that consumers use commercially available data-erasing software to ensure data is removed from the equipment prior to returning for recycling. Electronics recycler protocol is to wipe or physically destroy data-bearing electronic equipment, but it is prudent for residents to erase data out of an abundance of caution.

Only covered electronic equipment (TVs, computers, and other items listed above) will be accepted at these events for free from District households, small nonprofits, and small businesses.

Interested in being notified when events are posted, or if there are changes to event details once posted? To start getting alerts, please email [email protected] with the subject “Add to List”. Please include the number of the ward you live in so DOEE can see the ward distribution of who is interested in getting these notifications.

Important: By placing unwanted home computers at the curb, you offer identity thieves an opportunity to learn a lot about you. Your account numbers, passwords, and even social security number may be left behind in your electronics where dishonest people can find them. When your computer is taken to be recycled, however, your hard drive can be reformatted and all of your personal information permanently erased.

Upgrade what you have, rather than buying new. Instead of purchasing a new computer, for example, consider upgrading your current one with additional memory or new accessories.

Most computer monitors and televisions contain about five pounds of lead. Computers also contain other elements that, if improperly disposed of, can be environmental hazards (including metals and rechargeable batteries).

State law requires retailers of Nickel-Cadmium (Ni-Cad), Button and Lithium Ion batteries to accept them back for recycling. These retailers include: Best Buy, Lowes, Home Depot, Sears, Sprint, Target, Radio Shack, Batteries Plus, and Verizon Wireless. Effective Dec. 5, 2011, state law prohibits persons from knowingly disposing of most rechargeable batteries in the garbage.

NOTE--Regular household alkaline or zinc batteries can be disposed of in the trash. For a fee-based alkaline/zinc battery recycling program, visit: www.thinkgreenfromhome.com/batteries.cfm.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey