fda lcd monitors for import free sample

This page will provide an overview of medical and non-medical radiation-emitting electronic products and the requirements that FDA verifies/enforces at the time they are imported or offered for import into United States. To import radiation-emitting products (medical and non-medical) you should first understand what these products are and their requirements.

The Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) is the FDA center responsible for overseeing the radiation-emitting products program. Visit the Radiation-Emitting Products web page for more information.

FDA defines a radiation-emitting electronic product as any electrically-powered product that can emit any form of radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum. These include a variety of medical and non-medical products such as mammography devices, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices, laser toys, laser pointers, liquid crystal displays (LCDs), and light emitting diodes (LEDs). View examples of radiation-emitting electronic products.

FDA checks the import alert database to ensure the manufacturer or product is not subject to detention without physical exam (DWPE) and listed on an import alert. For example, import alert 95-04 lists certain laser products that fail to comply with applicable performance standards and reporting requirements.

Electronic products are subject to the Electronic Product Radiation Control (EPRC) provisions as defined in the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), Chapter 5, Subchapter C, Sections 532 – 538. Radiation-emitting electronic products are regulated by FDA and are required to comply with the general requirements found in 21 CFR 1000-1005. For more information on products subject to performance standards visit the Products Subject to Performance Standards page.

To search for product names and their associated product codes, the radiation type, definition, and applicable performance standards visit the Product Codes for Radiation-Emitting Electronic Products page.

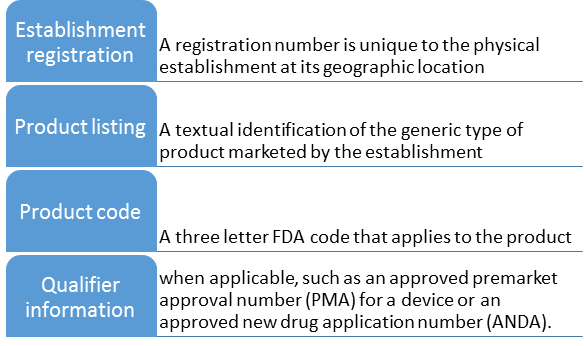

FDA Entry Reviewers are trained to verify compliance with applicable product requirements. The FDA Entry Reviewers use the information provided to FDA in the importer’s entry transmission such as:

These entry declarations are compared to information in FDA’s internal data systems. If the information matches, then compliance is verified; if the information does not match, FDA may gather additional information or may detain the product.

The submission of correct and accurate entry data along with the relevant A of C codes will help expedite the entry review process. Supplying this information accurately increases the likelihood that your shipment will be processed electronically and not held for manual review because FDA’s screening tool, PREDICT, can verify the declared information against FDA internal data systems.

Radiation-emitting electronic products can be considered medical and non-medical products. In addition to the requirements above, radiation-emitting electronic medical products are also subject to medical device regulations. At the time of importation FDA will verify radiation-emitting electronic product requirements (medical and non-medical).

Radiation-emitting electronic products subject to U.S. Federal Performance Standard require submission of Form FDA-2877, Declaration for Imported Electronic Products Subject to Radiation Control Standards, at the time of entry. Products not subject to federal performance standards do not require a Form FDA-2877 for importation into the US. At the time of importation FDA will verify the declarations submitted on Form FDA-2877.

Declaration C – Products that do not comply with performance standards are being held under temporary import bond (TIB); will not be introduced into commerce; will be used under a radiation protection plan; and will be destroyed or exported under CBP supervision when the mission is complete.

Declaration D - Products that do not comply with Performance Standards; are being held and will remain under bond; and will not be introduced into commerce until notification is received from FDA that the products have been brought into compliance in accordance with an FDA approved petition.

The process of “reconditioning” non-compliant radiation-emitting electronic products may be difficult and time consuming which could result in the importer losing the product and money if the reconditioning is unsuccessful. The importer should make a serious effort to understand the FDA radiation safety requirements that are applicable to the products being imported. Reconditioning requests are submitted using the Form FDA-766.

Affirmation of Compliance (A of C) codes are three letter codes that can be provided at the time of import to facilitate FDA review. FDA uses A of C codes to assist in verifying that your product meets the appropriate requirements. Providing the correct A of C code reduces the likelihood that your shipment will be held for further FDA entry review during FDA’s import screening process. Submission of A of C codes is only mandatory in some instances and is not required for all scenarios. Submitting voluntary A of C codes in addition to all mandatory A of C codes may expedite initial screening and review of your entry.

For information on affirmation of compliance codes refer to the “Affirmation Of Compliance References” at the bottom of the affirmation of compliance codes page.

Importation of radio frequency equipment requires that the product meet one of the eleven conditions as permitted in Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47 Section 2.1204 (please see import condition question one below).

Prior to July 1, 2016, importers were required to file FCC Form 740 in order to import devices, but that requirement was eliminated as of November 2, 2017 via FCC-17-93.

As of November 2, 2017, the requirement to submit a Form 740 has been eliminated, see FCC-17-93. Importation of radio frequency equipment still requires that the product: (1) Have the required FCC equipment authorization; (2) Is only being imported for evaluation purposes; (3) Is only being imported for demonstration at a trade show; or (4) Meets one of the conditions as permitted in Section 2.1204 (see Question 3 below).

The rules for importation are contained in Code Of Federal Regulations Title 47. Part 2, Subpart K – Importation of Devices Capable of Causing Harmful Interference.

Section 2.1204 of Part 2 Subpart K defines the 11 conditions that radio frequency devices may be imported. See https://www.fcc.gov/oet/ea/rfdevice and Knowledge Database (KDB) publication 997198 for guidance and definitions on Radio frequency devices.

The radio frequency device has been issued an equipment authorization by the FCC. The equipment has been approved per the required equipment authorization procedure (e.g., Certification or Supplier"s Declaration of Conformity (SDoC)) for the device being imported.

The radio frequency device is not required to have an equipment authorization, and the device complies with FCC technical administrative regulations. For example, products containing only digital logic that are exempt under Section 15.103..

The radio frequency device is being imported in quantities of 4,000 or fewer units for testing and evaluation to determine compliance with the FCC Rules and Regulations, product development, or suitability for marketing. The devices will not be offered for sale or marketed.

Prior to importation of a greater number of units, written approval must be obtained from the Chief, Office of Engineering and Technology, FCC (to request approval, see FAQ 8 below or KDB Publication 741304

The radio frequency device is being imported in limited quantities for demonstration at industry trade shows, and the device will not be offered for sale or marketed. The phrase "limited quantities," in this context means:

Prior to importation of a greater number of units than shown above, written approval must be obtained from the Chief, Office of Engineering and Technology, FCC. ( To request approval, see FAQ 8 below or KDB Publication 741304.)

If the device is a multi-mode wireless handset that has been certified under the Commission"s rules and a component (or components) of the handset is a foreign standard cellular phone solely capable of functioning outside the United States.

Three or fewer radio frequency devices are being imported for the individual"s personal use and are not intended for sale. Unless otherwise exempted, the permitted devices must be from one or more of the following categories:

The radio frequency device is a medical implant transmitter inserted in a person or a medical body-worn transmitter as defined in part 95, granted entry into the United States, or is a control transmitter associated with such an implanted or body-worn transmitter; provided, however that the transmitters covered by this provision otherwise comply with the technical requirements applicable to transmitters authorized to operate in the Medical Device Radiocommunication Service (MedRadio) under part 95. Such transmitters are permitted to be imported without the issuance of a grant of equipment authorization only for the personal use of the person in whom the medical implant transmitter has been inserted or on whom the medical body-worn transmitter is applied.

Three or fewer portable earth-station transceivers, as defined in Section 25.129, are being imported by a traveler as personal effects and will not be offered for sale or lease in the United States.

The radio frequency device is subject to Certification under § 2.907 and is being imported in quantities of 12,000 or fewer units for pre-sale activity. For purposes of this paragraph, quantities are determined by the number of devices with the same FCC ID.

The Chief, Office of Engineering and Technology, may approve importation of a greater number of units in a manner otherwise consistent with paragraph (a)(11) of section § 2.1204 in response to a specific request. See FAQ 8 below or KDB Publication 741304

Radiofrequency devices can only be imported under the exception of paragraph (11) of this section after compliance testing by an FCC-recognized accredited testing laboratory is completed and an application for certification is submitted to an FCC-recognized Telecommunication Certification Body pursuant to § 2.911 of this part;

Notwithstanding § 2.926, radiofrequency devices imported pursuant to paragraph (a)(11) of section § 2.1204 may include the expected FCC ID if obscured by the temporary label described in paragraph (a)(11)(iv)this section or, in the case of electronic labeling, if it cannot be viewed prior to authorization.

The radiofrequency devices must remain under legal ownership of the device manufacturer, developer, importer or ultimate consignee, or their designated customs broker, and only transferring physical possession of the devices for pre-sale activity as defined in paragraph (a)(11) of this section is permitted prior to Grant of Certification under § 2.907. The device manufacturer, developer, importer or ultimate consignee, or their designated customs broker must have processes in place to retrieve the equipment in the event that the equipment is not successfully certified and must complete such retrieval immediately after a determination is made that certification cannot be successfully completed.

The device manufacturer, developer, importer or ultimate consignee, or their designated customs broker must maintain, for a period of sixty (60) months, records identifying the recipient of devices imported for pre-sale activities. Such records must identify the device name and product identifier, the quantity shipped, the date on which the device authorization was sought, the expected FCC ID number, and the identity of the recipient, including contact information. The device manufacturer, developer, importer or ultimate consignee, or their designated customs broker must provide records maintained under this provision upon the request of Commission personnel.

The Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) codes are used to identify products subject to tariff requirements. There is no mapping between harmonization codes and FCC requirements. The FCC publishes a basic guidance to help importers and brokers to determine if a product is likely to be subject to FCC requirements, See: KDB Publication 997198. This guidance is only provided to help importers ensure that the product has been properly authorized and that a responsible party is identified. An importer may want to contact the manufacturer or the exporter to ensure that the product has been properly authorized according to the FCC rules.

Supplier"s Declaration of Conformity (SDoC) - The importer of record becomes the responsible party, and must be located within the United States and provide their name, address and telephone number or internet contact information as part of the compliance information for the end product documentation. The FCC has the right to request samples for inspection and submission of equipment for testing, and the test records as per the retention of records rules.

Certification – The responsible party is the party to whom the grant of certification is issued. The importer can rely on the foreign manufacturer for obtaining a certificate (grant of certification). The FCC may request samples for certified equipment for FCC inspection. If compliance issues arise, the grantee will be required to address those, or the grant may be subject to revocation or withdrawal of the equipment authorization. Withdrawal would result in the item not being able to be imported, marketed, or sold in the United States.

The equipment cannot be imported into the United States. Options to remedy this situation are to return the equipment to the originating port, or obtain a proper equipment authorization. In some cases, equipment may be placed in a bonded warehouse, or moved to a duty free zone while the application for authorization is being processed. After a proper equipment authorization has been obtained, the equipment can be imported.

The rules do not distinguish devices being imported for business or personal use and not for sale. The products must comply with the FCC requirements, unless subject to one of the exceptions identified as conditions (3) through (8) in FAQ 1.

6. What should I do if I left my electronic device in a foreign hotel, or I am returning goods I sent overseas to a trade show or for a demonstration?

Items not purchased overseas (personal items left behind or demonstrated overseas) that are being returned to the United States are technically re-importing goods that have previously been exported (or hand carried in the case of leaving a cell phone in a foreign hotel). They can be imported as returning personal goods.

8. How do I obtain a waiver of the quantity limitations as specified in the importation conditions: testing and evaluation or demonstration at industry trade shows, conditions 3 and 4 respectively (see FAQ 1)?

As of November 2, 2017, the requirement to file a Form 740 has been eliminated. As such there is no requirement to file information related to the importation of a RF device with the FCC. (See: FCC 17-93).

10. If the importation for pre-sale activity under section 2.1204 (a) (11) and the shipment to retailers or distribution centers is in the form of multi-unit packages (e.g., 12 individual devices in one package), is it acceptable to place the temporary label as required by section 2.1204 (a)(11)(iv) only on the outside of the multi-unit package, rather than on each individual device, provided the FCC-ID’s on the individual devices can’t be seen when enclosed in the multi-unit package?

Manufacturers, developers, importers or ultimate consignee, or their designated customs broker (responsible party) may fulfill the requirements of the rules 2.803 and 2.1204, by following the below alternative procedure. The responsible party for this alternative procedure must be the Grantee obtaining the intended certification of the devices being imported.

All devices to be imported under the alternative procedure without a temporary label on each device or device"s packaging must be physically secured, enclosed, and contained by a shrink-wrapped pallet, sealed shipping container, sealed carton, or other equivalent multi-unit package bulk enclosure.

The responsible party shall maintain a record of each bulk enclosure imported to include: Entry Number, Port of Entry, Date of Entry, Harmonized Tariff, Number, Total Quantity of items, Container Identification, and an inventory of each device by FCC ID(s) by device identification(i.e., serial number), appended to the information required by 2.1204(11)(vii).

The responsible party shall remain in possession of the bulk container as exclusive owner and in full control in their facilities (warehouse) until certification has been granted for the FCC IDs contained in that bulk enclosure.

If individual devices are removed from a bulk enclosure before an equipment authorization, the responsible party shall obscure the individual FCC Identifier for each device as required by 2.1204(11)(v) with a temporary label described in paragraph 2.1204(a)(11)(iv).

If the bulk enclosure is opened for any reason or inspected by customs and border protection officer, resulting in devices being removed from the bulk enclosure by others, the responsible party shall recover all items and re-secure in a bulk enclosure, or apply the temporary label, or if lost or destroyed document the details in the amended record required by item 2 above as appropriate.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is charged with preventing deception and unfairness in the marketplace. The FTC Act gives the Commission the power to bring law enforcement actions against false or misleading claims that a product is of U.S. origin. Traditionally, the Commission has required that a product advertised as Made in USA be "all or virtually all" made in the U.S. After a comprehensive review of Made in USA and other U.S. origin claims in product advertising and labeling, the Commission announced in December 1997 that it would retain the "all or virtually all" standard. The Commission also issued an Enforcement Policy Statement on U.S. Origin Claims to provide guidance to marketers who want to make an unqualified Made in USA claim under the "all or virtually all" standard and those who want to make a qualified Made in USA claim.

This publication provides additional guidance about how to comply with the "all or virtually all" standard. It also offers some general information about the U.S. Customs Service’s requirement that all products of foreign origin imported into the U.S. be marked with the name of the country of origin.

This publication is the Federal Trade Commission staff’s view of the law’s requirements. It is not binding on the Commission. The Enforcement Policy Statement issued by the FTC is at the end of the publication.

The policy applies to all products advertised or sold in the U.S., except for those specifically subject to country-of-origin labeling by other laws. Other countries may have their own country-of-origin marking requirements. As a result, exporters should determine whether the country to which they are exporting imposes such requirements.

The Enforcement Policy Statement applies to U.S. origin claims that appear on products and labeling, advertising, and other promotional materials. It also applies to all other forms of marketing, including marketing through digital or electronic mechanisms, such as Internet or e-mail.

In identifying implied claims, the Commission focuses on the overall impression of the advertising, label, or promotional material. Depending on the context, U.S. symbols or geographic references (for example, U.S. flags, outlines of U.S. maps, or references to U.S. locations of headquarters or factories) may convey a claim of U.S. origin either by themselves, or in conjunction with other phrases or images.

Example: A product is manufactured abroad by a well-known U.S. company. The fact that the company is headquartered in the U.S. also is widely known. Company pamphlets for its foreign-made product prominently feature its brand name. Assuming that the brand name does not specifically denote U.S. origin (that is, the brand name is not "Made in America, Inc."), using the brand name by itself does not constitute a claim of U.S. origin.

The Commission does not pre-approve advertising or labeling claims. A company doesn’t need approval from the Commission before making a Made in USA claim. As with most other advertising claims, a manufacturer or marketer may make any claim as long as it is truthful and substantiated.

For a product to be called Made in USA, or claimed to be of domestic origin without qualifications or limits on the claim, the product must be "all or virtually all" made in the U.S. The term "United States," as referred to in the Enforcement Policy Statement, includes the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories and possessions.

"All or virtually all" means that all significant parts and processing that go into the product must be of U.S. origin. That is, the product should contain no — or negligible — foreign content.

The product’s final assembly or processing must take place in the U.S. The Commission then considers other factors, including how much of the product’s total manufacturing costs can be assigned to U.S. parts and processing, and how far removed any foreign content is from the finished product. In some instances, only a small portion of the total manufacturing costs are attributable to foreign processing, but that processing represents a significant amount of the product’s overall processing. The same could be true for some foreign parts. In these cases, the foreign content (processing or parts) is more than negligible, and, as a result, unqualified claims are inappropriate.

Example: A company produces propane barbecue grills at a plant in Nevada. The product’s major components include the gas valve, burner and aluminum housing, each of which is made in the U.S. The grill’s knobs and tubing are imported from Mexico. An unqualified Made in USA claim is not likely to be deceptive because the knobs and tubing make up a negligible portion of the product’s total manufacturing costs and are insignificant parts of the final product.

Example: A table lamp is assembled in the U.S. from American-made brass, an American-made Tiffany-style lampshade, and an imported base. The base accounts for a small percent of the total cost of making the lamp. An unqualified Made in USA claim is deceptive for two reasons: The base is not far enough removed in the manufacturing process from the finished product to be of little consequence and it is a significant part of the final product.

Should manufacturers and marketers rely on information from American suppliers about the amount of domestic content in the parts, components, and other elements they buy and use for their final products?

If given in good faith, manufacturers and marketers can rely on information from suppliers about the domestic content in the parts, components, and other elements they produce. Rather than assume that the input is 100 percent U.S.-made, however, manufacturers and marketers would be wise to ask the supplier for specific information about the percentage of U.S. content before they make a U.S. origin claim.

Example: A company manufactures food processors in its U.S. plant, making most of the parts, including the housing and blade, from U.S. materials. The motor, which constitutes 50 percent of the food processor’s total manufacturing costs, is bought from a U.S. supplier. The food processor manufacturer knows that the motor is assembled in a U.S. factory. Even though most of the parts of the food processor are of U.S. origin, the final assembly is in the U.S., and the motor is assembled in the U.S., the food processor is not considered "all or virtually all" American-made if the motor itself is made of imported parts that constitute a significant percentage of the appliance’s total manufacturing cost. Before claiming the product is Made in USA, this manufacturer should look to its motor supplier for more specific information about the motor’s origin.

Example: On its purchase order, a company states: "Our company requires that suppliers certify the percentage of U.S. content in products supplied to us. If you are unable or unwilling to make such certification, we will not purchase from you." Appearing under this statement is the sentence, "We certify that our ___ have at least ___% U.S. content," with space for the supplier to fill in the name of the product and its percentage of U.S. content. The company generally could rely on a certification like this to determine the appropriate country-of-origin designation for its product.

To determine the percentage of U.S. content, manufacturers and marketers should look back far enough in the manufacturing process to be reasonably sure that any significant foreign content has been included in their assessment of foreign costs. Foreign content incorporated early in the manufacturing process often will be less significant to consumers than content that is a direct part of the finished product or the parts or components produced by the immediate supplier.

Example: The steel used to make a single component of a complex product (for example, the steel used in the case of a computer’s floppy drive) is an early input into the computer’s manufacture, and is likely to constitute a very small portion of the final product’s total cost. On the other hand, the steel in a product like a pipe or a wrench is a direct and significant input. Whether the steel in a pipe or wrench is imported would be a significant factor in evaluating whether the finished product is "all or virtually all" made in the U.S.

Example: If the gold in a gold ring is imported, an unqualified Made in USA claim for the ring is deceptive. That’s because of the significant value the gold is likely to represent relative to the finished product, and because the gold — an integral component — is only one step back from the finished article. By contrast, consider the plastic in the plastic case of a clock radio otherwise made in the U.S. of U.S.-made components. If the plastic case was made from imported petroleum, a Made in USA claim is likely to be appropriate because the petroleum is far enough removed from the finished product, and is an insignificant part of it as well.

A qualified Made in USA claim is appropriate for products that include U.S. content or processing but don’t meet the criteria for making an unqualified Made in USA claim. Because even qualified claims may imply more domestic content than exists, manufacturers or marketers must exercise care when making these claims. That is, avoid qualified claims unless the product has a significant amount of U.S. content or U.S. processing. A qualified Made in USA claim, like an unqualified claim, must be truthful and substantiated.

Example: An exercise treadmill is assembled in the U.S. The assembly represents significant work and constitutes a "substantial transformation" (a term used by the U.S. Customs Service). All of the treadmill’s major parts, including the motor, frame, and electronic display, are imported. A few of its incidental parts, such as the handle bar covers, the plastic on/off power key, and the treadmill mat, are manufactured in the U.S. Together, these parts account for approximately three percent of the total cost of all the parts. Because the value of the U.S.-made parts is negligible compared to the value of all the parts, a claim on the treadmill that it is "Made in USA of U.S. and Imported Parts" is deceptive. A claim like "Made in U.S. from Imported Parts" or "Assembled in U.S.A." would not be deceptive.

Claims that a particular manufacturing or other process was performed in the U.S. or that a particular part was manufactured in the U.S. must be truthful, substantiated, and clearly refer to the specific process or part, not to the general manufacture of the product, to avoid implying more U.S. content than exists.

In addition, if a product is of foreign origin (that is, it has been substantially transformed abroad), manufacturers and marketers also should make sure they satisfy Customs’ markings statute and regulations that require such products to be marked with a foreign country of origin. Further, Customs requires the foreign country of origin to be preceded by "Made in," "Product of," or words of similar meaning when any city or location that is not the country of origin appears on the product.

Example: A company designs a product in New York City and sends the blueprint to a factory in Finland for manufacturing. It labels the product "Designed in USA — Made in Finland." Such a specific processing claim would not lead a reasonable consumer to believe that the whole product was made in the U.S. The Customs Service requires the product to be marked "Made in," or "Product of" Finland since the product is of Finnish origin and the claim refers to the U.S. Examples of other specific processing claims are: "Bound in U.S. — Printed in Turkey." "Hand carved in U.S. — Wood from Philippines." "Software written in U.S. — Disk made in India." "Painted and fired in USA. Blanks made in (foreign country of origin)."

Example: A computer imported from Korea is packaged in the U.S. in an American-made corrugated paperboard box containing only domestic materials and domestically produced expanded rigid polystyrene plastic packing. Stating Made in USA on the package would deceive consumers about the origin of the product inside. But the company could legitimately make a qualified claim, such as "Computer Made in Korea — Packaging Made in USA."

Example: The Acme Camera Company assembles its cameras in the U.S. The camera lenses are manufactured in the U.S., but most of the remaining parts are imported. A magazine ad for the camera is headlined "Beware of Imported Imitations" and states "Other high-end camera makers use imported parts made with cheap foreign labor. But at Acme Camera, we want only the highest quality parts for our cameras and we believe in employing American workers. That’s why we make all of our lenses right here in the U.S." This ad is likely to convey that more than a specific product part (the lens) is of U.S. origin. The marketer should be prepared to substantiate the broader U.S. origin claim conveyed to consumers viewing the ad.

Comparative claims should be truthful and substantiated, and presented in a way that makes the basis for comparison clear (for example, whether the comparison is to another leading brand or to a previous version of the same product). They should truthfully describe the U.S. content of the product and be based on a meaningful difference in U.S. content between the compared products.

Example: An ad for cellular phones states "We use more U.S. content than any other cellular phone manufacturer." The manufacturer assembles the phones in the U.S. from American and imported components and can substantiate that the difference between the U.S. content of its phones and that of the other manufacturers’ phones is significant. This comparative claim is not deceptive.

Example: A product is advertised as having "twice as much U.S. content as before." The U.S. content in the product has been increased from 2 percent in the previous version to 4 percent in the current version. This comparative claim is deceptive because the difference between the U.S. content in the current and previous version of the product are insignificant.

A product that includes foreign components may be called "Assembled in USA" without qualification when its principal assembly takes place in the U.S. and the assembly is substantial. For the "assembly" claim to be valid, the product’s last "substantial transformation" also should have occurred in the U.S. That’s why a "screwdriver" assembly in the U.S. of foreign components into a final product at the end of the manufacturing process doesn’t usually qualify for the "Assembled in USA" claim.

Example: A lawn mower, composed of all domestic parts except for the cable sheathing, flywheel, wheel rims and air filter (15 to 20 percent foreign content) is assembled in the U.S. An "Assembled in USA" claim is appropriate.

Example: All the major components of a computer, including the motherboard and hard drive, are imported. The computer’s components then are put together in a simple "screwdriver" operation in the U.S., are not substantially transformed under the Customs Standard, and must be marked with a foreign country of origin. An "Assembled in U.S." claim without further qualification is deceptive.

The Tariff Act gives Customs and the Secretary of the Treasury the power to administer the requirement that imported goods be marked with a foreign country of origin (for example, "Made in Japan").

When an imported product incorporates materials and/or processing from more than one country, Customs considers the country of origin to be the last country in which a "substantial transformation" took place. Customs defines "substantial transformation" as a manufacturing process that results in a new and different product with a new name, character, and use that is different from that which existed before the change. Customs makes country-of-origin determinations using the "substantial transformation" test on a case-by-case basis. In some instances, Customs uses a "tariff shift" analysis, comparable to "substantial transformation," to determine a product’s country of origin.

Even if Customs determines that an imported product does not need a foreign country-of-origin mark, it is not necessarily permissible to promote that product as Made in USA. The FTC considers additional factors to decide whether a product can be advertised or labeled as Made in USA.

Manufacturers and marketers should check with Customs to see if they need to mark their products with the foreign country of origin. If they don’t, they should look at the FTC’s standard to check if they can properly make a Made in USA claim.

The FTC has jurisdiction over foreign origin claims on products and in packaging that are beyond the disclosures required by Customs (for example, claims that supplement a required foreign origin marking to indicate where additional processing or finishing of a product occurred).

The FTC also has jurisdiction over foreign origin claims in advertising and other promotional materials. Unqualified U.S. origin claims in ads or other promotional materials for products that Customs requires a foreign country-of-origin mark may mislead or confuse consumers about the product’s origin. To avoid misleading consumers, marketers should clearly disclose the foreign manufacture of a product.

Example: A television set assembled in Korea using an American-made picture tube is shipped to the U.S. The Customs Service requires the television set to be marked "Made in Korea" because that’s where the television set was last "substantially transformed." The company’s World Wide Web page states "Although our televisions are made abroad, they always contain U.S.-made picture tubes." This statement is not deceptive. However, making the statement "All our picture tubes are made in the USA" — without disclosing the foreign origin of the television’s manufacture — might imply a broader claim (for example, that the television set is largely made in the U.S.) than could be substantiated. That is, if the statement and the entire ad imply that any foreign content or processing is negligible, the advertiser must substantiate that claim or net impression. The advertiser in this scenario would not be able to substantiate the implied Made in USA claim because the product was "substantially transformed" in Korea.

Textile Fiber Products Identification Act and Wool Products Labeling Act — Require a Made in USA label on most clothing and other textile or wool household products if the final product is manufactured in the U.S. of fabric that is manufactured in the U.S., regardless of where materials earlier in the manufacturing process (for example, the yarn and fiber) came from. Textile products that are imported must be labeled as required by the Customs Service. A textile or wool product partially manufactured in the U.S. and partially manufactured in another country must be labeled to show both foreign and domestic processing.

Catalogs and other mail order promotional materials for textile and wool products, including those disseminated on the Internet, must disclose whether a product is made in the U.S., imported or both.

The Fur Products Labeling Act requires the country of origin of imported furs to be disclosed on all labels and in all advertising. For copies of the Textile, Wool or Fur Rules and Regulations, or the new business education guide on labeling requirements, call the FTC’s Consumer Response Center

American Automobile Labeling Act — Requires that each automobile manufactured on or after October 1, 1994, for sale in the U.S. bear a label disclosing where the car was assembled, the percentage of equipment that originated in the U.S. and Canada, and the country of origin of the engine and transmission. Any representation that a car marketer makes that is required by the AALA is exempt from the Commission’s policy. When a company makes claims in advertising or promotional materials that go beyond the AALA requirements, it will be held to the Commission’s standard. For more information, call the Consumer Programs Division of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (202-366-0846).

Buy American Act — Requires that a product be manufactured in the U.S. of more than 50 percent U.S. parts to be considered Made in USA for government procurement purposes. For more information, review the Buy American Act at 41 U.S.C. §§ 10a-10c, the Federal Acquisition Regulations at 48 C.F.R. Part 25, and the Trade Agreements Act at 19 U.S.C. §§ 2501-2582.

Information about possible illegal activity helps law enforcement officials target companies whose practices warrant scrutiny. If you suspect noncompliance, contact the Division of Enforcement, Bureau of Consumer Protection, Federal Trade Commission, Washington, DC 20580; (202) 326-2996 or send an e-mail to MUSA@ftc.gov. If you know about import or export fraud, call Customs’ toll-free Commercial Fraud Hotline, 1-800-ITS-FAKE. Examples of fraudulent practices involving imports include removing a required foreign origin label before the product is delivered to the ultimate purchaser (with or without the improper substitution of a Made in USA label) and failing to label a product with a required country of origin.

Finally, the Lanham Act gives any person (such as a competitor) who is damaged by a false designation of origin the right to sue the party making the false claim. Consult a lawyer to see if this private right of action is an appropriate course of action for you.

The FTC works for the consumer to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, and unfair business practices in the marketplace and to provide information to help consumers spot, stop, and avoid them. To file a complaint or to get free information on consumer issues, visit ftc.gov or call toll-free, 1-877-FTC-HELP (1-877-382-4357); TTY: 1-866-653-4261. The FTC enters consumer complaints into the Consumer Sentinel Network, a secure online database and investigative tool used by hundreds of civil and criminal law enforcement agencies in the U.S. and abroad.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This guide serves as an ongoing report of the most recent FDA inspection and enforcement trends, specifically in the area of good manufacturing practice (GMP), based on publicly available data. We"ve included a mix of our firsthand research along with others" analyses and links to the appropriate sources.

Note that the data presented here conform to the fiscal year accounting period for the federal government, which begins on October 1 and ends on September 30. The fiscal year is designated by the calendar year in which it ends.

In November 2022, Jeffrey Meng, program division director, Division of Pharmaceutical Quality Operations III, Office of Regulatory Affairs, stated that the backlog of foreign and domestic onsite inspections for sites considered a high priority. "Looking forward to 2023 and beyond, we have resumed all routine domestic operations and are currently resuming normal foreign inspections. This opening of worldwide operations for FDA will be and is an incredible challenge.” (RAPS)

The number of domestic FDA inspections related to drugs rose from 713 in FY2021 to 756 in FY2022, a ~6% increase. The number of foreign FDA inspections related to drugs rose from 130 in FY2021 to 262 in FY2022, a ~101% increase. (FDA data dashboard)

The number of domestic FDA inspections related to devices rose from 382 in FY2021 to 935 in FY2022, a ~144% increase. The number of foreign FDA inspections related to devices rose from only 4 in FY2021 to 79 in FY2022, a whopping 1875% increase. (FDA data dashboard)

For example, not all inspections are included in the database. Inspections conducted by states, pre-approval inspections, mammography facility inspections, inspections waiting for a final enforcement action, and inspections of nonclinical labs are not included.

#4 —21 CFR 211.100(a) — There shall be written procedures for production and process control designed to assure that the drug products have the identity, strength, quality, and purity they purport or are represented to possess...

#6 — 21 CFR 211.67(b)— Written procedures shall be established and followed for cleaning and maintenance of equipment, including utensils, used in the manufacture, processing, packing, or holding of a drug product...

#7 — 21 CFR 211.25(a) — Each person engaged in the manufacture, processing, packing, or holding of a drug product shall have education, training, and experience, or any combination thereof, to enable that person to perform the assigned functions...

#9 — 21 CFR 211.67(a) — Equipment and utensils shall be cleaned, maintained, and, as appropriate for the nature of the drug, sanitized and/or sterilized at appropriate intervals to prevent malfunctions or contamination that would alter the safety, identity, strength, quality, or purity of the drug product beyond the official or other established requirements.

#10 — 21 CFR 211.110(a) — To assure batch uniformity and integrity of drug products, written procedures shall be established and followed that describe the in-process controls, and tests, or examinations to be conducted on appropriate samples of in-process materials of each batch. Such control procedures shall be established to monitor the output and to validate the performance of those manufacturing processes that may be responsible for causing variability in the characteristics of in-process material and the drug product...

Given that FDA"s inspectional citations specify different descriptions and particular subparts, the interactive chart below breaks down these details to show the relative prevalence of certain observed issues over others.

— Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures to ensure that all purchased or otherwise received product and services conform to specified requirements.

#4 —21 CFR 820.90(a) — Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures to control product that does not conform to specified requirements...

— Each manufacturer shall establish procedures for quality audits and conduct such audits to assure that the quality system is in compliance with the established...

Given that FDA"s inspectional citations specify different descriptions and particular subparts, the interactive chart below breaks down these details to show the relative prevalence of certain observed issues over others.

In 2022, the Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ) within FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) published its fiscal year 2021 report on the state of pharmaceutical quality. We distilled some of its main takeaways below.

OPQ said its New Inspection Protocol Project (NIPP) program has increased the efficiency of inspections through a more targeted and data-driven approach to identify potential quality problems early on. FDA says its NIPP has “improved how data from pre-approval and surveillance inspections are evaluated and reported.” (FDA has been using these inspection protocols for certain sterile surveillance and pre-approval inspections since 2018.)

Sites making “essential medicines” that protect the public against outbreaks of emerging diseases such as COVID-19 have high median site inspection scores (SIS), indicating a high rate of compliance with GMP. An analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and finished dosage form (FDF) sites found that the median SIS for essential medicine manufacturers was 7.45 out of 10, a score that was “significantly higher” than the 7.0 score for non-essential medicine manufacturers. “This observation indicates that sites manufacturing EM products have a higher level of adherence to manufacturing compliance standards than sites that do not manufacture EM products,” OPQ wrote.

For the second year, the number of total recalls (particularly Class I recalls) has increased. This follows a three-year period of declining recalls from FY2017 to FY2019. Since FY2016, recalls spiked up dramatically, going from roughly 300 recalls events a year in 2019 to 700 in FY2020 to 800 in FY2021. Hand sanitizers that contained methanol, as well as consumer products and sunscreens with benzene contamination are largely to blame for the increase.

Roughly half (49.1%) of 1,143 eligible firms did not submit field alert reports (FARs) to the agency over a four-year period from FY2018 to FY2021. FDA’s postmarket reporting requirements specify that sites submit FARs after receiving information on significant quality problems with their distributed drug products.

A growing number of products are failing sampling and testing requirements; a method of inspection is used when FDA cannot get to sites to conduct inspections. In FY2021, the percentage of non-compliant samples grew to 35%, an increase from 16% in FY2020. The growing rate of non-compliance “is driven by focused sampling assignments with high non-compliant rates for products with nitrosamine contamination, hand sanitizers, and sampling related to COVID-19 mission critical sampling and testing, which became more prominent in FY2021.“

Read FDA"s full FY2022 report (PDF) on fda.govhere. We distilled some of its main takeaways below. Read our blog post for more depth into some of these takeaways.

FDA used Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) and its authority to obtain records for sites in advance or in lieu of inspections due to the pandemic.In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act gave FDA new authorities under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act §704(a)(4) to request records or other information from firms in advance of or in lieu of an inspection.

“FDA surveillance history, requests for records, and inspection reports obtained through the MRAs were all used to mitigate risk and enable regulatory actions.”

“MRA authority was used to assess 183 sites through MRA inspection reports for a total of 745 sites (18% of the FY2020 CDER Site Catalog). For comparison, in FY2019 1,258 drug quality assurance inspections were performed and an additional 109 sites were assessed using MRAs for a total of 1,367 sites (32% of the FY2020 CDER Site Catalog).”

“As in past years, the majority of Warning Letters in FY2020 were issued to sites with non-application products (69%), and especially those that manufacture finished dosage form (FDF), non-sterile, non-application products (41% of all Warning Letters).”

“Import Alerts doubled to 128 in FY2020. Latin America had the most sites on Import Alert for the first time in FY2020, due to an unprecedented number of new hand sanitizer registrants from Mexico that failed to meet quality standards."

Since FY2019, there has been a small decrease (0.10) in the mean Site Inspection Score (SIS) of the entire inventory of sites (7.3).FDA’s SIS, a scale of 1 to 10, is used as a proxy for compliance with CGMP regulations. The SIS is based on the classification of FDA drug quality assurance inspections conducted over the prior ten years, including inspections classified under the MRA program, which allows some global regulators to recognize reports from their counterparts’ inspections.

“For FY2016–FY2020, three defect categories account for 60% of all defects reported: Product Quality Questioned, Device Issues, and Packaging Issues.”

“The most substantial increases in the number of recalls by industry sector in FY2020 were in the No Application and NDA & ANDA (i.e., sites manufacturing for both application types) sectors.” (See full report for additional details.)

“Each major recall over the last five fiscal years was associated with microbial or chemical contamination/impurities; a focus area for the industry to improve quality.”

CDER will continue to seek to minimize long-standing problems such as drug shortages due to quality issues through proactive efforts including the New Inspection Protocol Project (NIPP) and Quality Management Maturity. The NIPP “is aimed at using standardized electronic inspection protocols to collect data in a structured manner. The protocols promote consistent and comprehensive coverage of critical areas of drug manufacturing and provide structured, data-rich reports.

“In the future, FDA will have the ability to better understand how certain variables (e.g., location of the establishment, type of establishment) affect quality. As more data are collected through NIPP, these types of insights can inform future inspections, identify policy/outreach opportunities, and influence application-related decision making."

A report published by the ECA Academy looked back from October 2018 to September 2019 to review the FDA warning letter trends among pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Where applicable, we’ve provided links to relevant resources and next steps for those looking for guidance and assistance in mitigating trending risks.

The specific issues contained within these recent warning letters reveal a continuation of a trend that’s been running for years: lapses in meeting basic GMP requirements.

As analyzed and compiled by Barbara Unger in an impressively researched column for Pharmaceutical Online, the frequency of Forms 483 issued to pharmaceutical companies has continued its steady rise over the past few years.

Note that for this and the following sections covering inspection observation trends, the data presented adheres to the analysis methodology and limitations described in the introduction of the

Again, given the caveat of the limited public data available (the FDA’s data includes only Forms 483 issued through its electronic system and omits API manufacturers), some notable findings emerge regarding specific §211 citations.

As we explored in another article, 2019 saw the FDA put a greater compliance focus on over-the-counter (OTC) drugs and other health product manufacturers. In a July 2019 column for Pharmaceutical Online, we analyzed these OTC-specific compliance trends, pulling out the following common issues appearing in warning letters.

Nonconformance Management —Another recent trend afflicting OTC drugmakers mirrors a broader and well-documented trend throughout the drug and device space: inadequate nonconformance management. As demonstrated by a large number of citations issued specifically for “inadequate, incomplete, and undocumented investigations,” these warning letters offer evidence of a long-standing perception that an outsized focus is placed on immediate nonconformance correction rather than on thoroughly investigating and executing corrective and preventive actions following a comprehensive root cause analysis.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Authority of the Quality Unit —The internal quality unit (QU) has been the target of many recent warning letters to OTC drug and health product manufacturers as an underlying cause of product quality and GMP compliance problems. Numerous firms have been cited for having an inadequate QU. In the most egregious examples, firms lacked this designated team entirely. More often, however, regulators have cited firms for a lack of written procedures that govern the responsibilities and functions of this group. 21 CFR Part 211 is clear about the need to establish a “quality control unit” with the documented responsibility and authority to make critical decisions.

Based on a growing number of relevant warning letters, as well as analyses of enforcement trend data and public statements made by the FDA, it’s clear that a renewed focus has been placed on evaluating manufacturers of OTC drug and health products in key areas of GMP.

These areas of enforcement focus include ineffective quality units, poor testing of incoming materials and components (i.e., relying on a supplier’s certificate of analysis), poor product testing, poor analytical and microbial testing and validation methodology (including method suitability), and inadequate nonconformance management.

Here are the major takeaways for inspections and compliance, specifically back from FDA"s Report on the State of Pharmaceutical Quality: Fiscal Year 2019 :

Based on its 10-point inspection score, the overall average for inspections in FY2019 was 7.4.(US- and EU-based sites scored averages that were slightly higher: 7.7 and 7.6, respectively.)

Based on its 10-point inspection score, homeopathic products and sterile over-the-counter (OTC) products had the lowest average scores at 6.5 and 6.2, respectively. For more on recent chronic quality and compliance issues among OTC and health product manufacturers,

In its report, regulators went on to say, "These sections represent some of the key elements of an effective Pharmaceutical Quality System. These are potential areas of focus for manufacturing facility management to improve overall pharmaceutical quality and inspectional outcomes."

Publicly available warning letters and inspection observation data provide powerful resources for understanding areas of regulatory focus and a benchmark for evaluating potential vulnerabilities within the quality system and beyond.

In many of its warning letters, the FDA has “strongly recommended” engaging a third-party consultant qualified in the relevant regulations to assist in meeting CGMP requirements.

While we help many companies resolve Forms 483 and warning letters, we also help prevent them from being issued in the first place. At The FDA Group, we plan and conduct effective internal quality audits to ensure your quality system is completely aligned with all documentation and operations — the critical part of any internal audit.

to remain available until expended. Payment under title XIX may be made for any quarter with respect to a State plan or plan amendment in effect during such quarter, if submitted in or prior to such quarter and approved in that or any subsequent quarter. This section provides an advanced appropriation for the first quarter of fiscal year

for unanticipated costs, incurred for the current fiscal year, such sums as may be necessary. For making payments to States or in the case of section 1928 on behalf of States under title XIX for the first quarter of fiscal year

removed the exception which allowed payment for abortions in those instances where severe and long lasting physical health damage to the mother would result if the pregnancy were carried to term when so determined by two physicians.

None of the funds appropriated under this Act shall be expended for any abortion. (b) None of the funds appropriated under this Act shall be expended for health benefits coverage that includes coverage of abortion. (c) The term health benefits coverage" means the package of services covered by a managed care provider or

for managing risk, developing security policies, assigning responsibilities, and monitoring the adequacy of the entity"s computer-related controls; • access controls that limit or detect access to computer resources (data, equipment, and facilities) thereby protecting these resources against unauthorized modification, loss, and disclosure;

to perform PT for specific tests. CLIA defines laboratory testing as “the examination of materials derived from the human body for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, or treatment of any disease or impairment of, or the assessment of the health of human beings.” There are approximately 170,000 CLIA certified laboratories. Fifty percent of these laboratories perform test methodologies that are so simple and accurate that the

This page is recommended for advanced users. It explains how to download study record data in Extensible Markup Language (XML), a machine-readable format, and in other data formats.

The Download option on the Search Results page is an advanced feature that allows you to download information about some or all of the studies shown in the search results:

For example, if your search finds fewer than 1,000 studies, "Top 10 Studies" and "Top 100 Studies" can be selected, but "Top 1000 Studies" will not appear in the dropdown list.

All studies retrieved by your search (up to a maximum of 10,000 study records). For example, if your search finds 54 studies, "54 Found Studies" will appear in the dropdown list.

Use the dropdown menu to choose which table columns are downloaded for each study and in what format:Displayed Columns. Choose this option to download only table columns shown onscreen. The default study columns shown onscreen are Row, Status, Study Title, Condition and Interventions.

All Available Columns. Choose this option to download all available table columns. Includes over 20 columns such as Status, Conditions, Interventions, Study Type, Phase, and Sponsor/Collaborators. For more information about columns, see Customize Your Search Results Display.

Use the dropdown list to select one of the following formats for your saved file:PDF. Save as Portable Document Format (PDF), a standard format accessible using the freely available

Tab-separated values. Save each study as a separate line in the file, with tabs as delimiters, or spacers, between each field. This format is useful for importing study information into spreadsheets and databases.

Comma-separated values. Save each study as a separate line in the file, with commas as delimiters, or spacers, between each field. This format is useful for importing study information into spreadsheets and databases.

Click on the Download button under "For Advanced Users:" to save the complete XML for all study records (that is, all registration information as well as any available results information) retrieved by your search (up to a maximum of 1,000 study records) as a zip file or compressed package to your computer. (Sample zip file readers with free trial periods:

The ClinicalTrials.gov Application Programming Interface (API) provides a toolbox for programmers and other technical users to access publicly accessible information for all study records posted on ClinicalTrials.gov. For example, the API can be used to encode a search query as a URL. Clicking on the URL activates the query to search and retrieve study records from ClinicalTrials.gov.

A single zip file containing all study records available on ClinicalTrials.gov (that is, all registration information as well as any available results information for all study records) in XML format is available here:

Additionally, many receiving systems may subject the zip file to automatic security/virus scanning. This scanning may take several additional minutes to complete before the zip file is ready for use. Please be patient.

The zip file contains multiple directories subdividing the large number of files into more manageable quantities. A top level "Contents.txt" file contains information about the number of study records

Supporting information, such as a data dictionary, database schema, and a guide for researchers and analysts, are also available on the AACT database page.

New Scientist magazine was launched in 1956 "for all those men and women who are interested in scientific discovery, and in its industrial, commercial and social consequences". The brand"s mission is no different today - for its consumers, New Scientist reports, explores and interprets the results of human endeavour set in the context of society and culture.

No. SmartBP allows you to record, track and analyze trends in your blood pressure. You can either manually enter your records or use a blood pressure monitor to sync with SmartBP through Apple Health or a SmartBP® connected Blood Pressure Monitor. SmartBP alone does not measure blood pressure. You need a separate blood pressure monitor to measure blood pressure. Make sure that the blood pressure monitor you select meets your country"s regulatory requirements (e.g. US FDA, EU MDR, etc.).

Yes. You can download SmartBP for free on both Apple and Android devices. You can upgrade to premium version anytime. The premium version requires a subscription and includes features such as Apple Watch integration, Print or Share PDF Reports, iPhone / iPad direct wireless sync, SmartBP Cloud sync, advanced analysis features, import/export files to Dropbox and Google Drive, and of course no Ads.

For users who do not want to share their data in the cloud, we provide an option to sync between iPhone and iPad directly. You should have the premium version of SmartBP running on both devices. After making a purchase on one device, you are NOT charged again for the app on another device. Go to the More section of the SmartBP and select "Restore Purchase". You will only be charged once and not twice. You restore your purchase for free.

First set one device to receive fro

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey