lcd display no backlight free sample

Newhaven 160x100 graphic Chip-On-Glass (COG) Liquid Crystal Display shows dark pixels on a gray background. This reflective LCD Display is visible with high ambient light while offering a wide operating temperature range from -20 to 70 degrees Celsius. This NHD-C160100CZ-RN-FBW display has an optimal view of 6:00 and has no backlight. This display operates at 3V supply voltage and is RoHS compliant.

Adjust the length, position, and pinout of your cables or add additional connectors. Get a cable solution that’s precisely designed to make your connections streamlined and secure.

Easily modify any connectors on your display to meet your application’s requirements. Our engineers are able to perform soldering for pin headers, boxed headers, right angle headers, and any other connectors your display may require.

Choose from a wide selection of interface options or talk to our experts to select the best one for your project. We can incorporate HDMI, USB, SPI, VGA and more into your display to achieve your design goals.

Choose from a wide selection of changes including shape, size, pinout, and component layout of your PCB to make it a perfect fit for your application.

Newhaven 40x4 character Liquid Crystal Display shows characters with dark pixels on a gray background. This reflective LCD Display is visible with high ambient light while offering a wide operating temperature range from -20 to 70 degrees Celsius. This NHD-0440AZ-RN-FBW display has an optimal view of 6:00 and has no backlight. This display operates at 5 supply voltage and is RoHS compliant.

Adjust the length, position, and pinout of your cables or add additional connectors. Get a cable solution that’s precisely designed to make your connections streamlined and secure.

Easily modify any connectors on your display to meet your application’s requirements. Our engineers are able to perform soldering for pin headers, boxed headers, right angle headers, and any other connectors your display may require.

Choose from a wide selection of interface options or talk to our experts to select the best one for your project. We can incorporate HDMI, USB, SPI, VGA and more into your display to achieve your design goals.

Choose from a wide selection of changes including shape, size, pinout, and component layout of your PCB to make it a perfect fit for your application.

Compared with lcd displays in bulk available, Alibaba.com offers both options of them. For lcd displays and bulk functions, Lcd displays provide more functions and are aesthetically pleasing.

Both lcd displays and Lcd enable similar functions and arefabricated from the source. Lcd displays, on the other hand, are more conventional and can be used for a variety of purposes.

Find wholesale lcd displays in bulk, Alibaba.com offers a wide variety of options. For the buyers who are looking for a more portable LCD display in bulk, that are the for.imum brightness in the future. Many lcd displays in bulk will have a better brightness future than.

Unlike conventional displays, lcd displays offer more buttons and interfaces for other information, as well as a mechanism. Find a variety of lcd displays available on Alibaba.com to stock and stock lcd displays with different features, such as touch sensitive, light-emitting diodesal, or LED signals.

I"ve been working on an iPad 2 that was dropped. It worked fine, despite the digitizer glass being shattered. I carefully disassembled the unit and installed a new Digitizer. Before sealing the digitizer in place, I tested the iPad. I discovered that the LCD backlight was not working. I reseated all cables. No change. I inspected the unit for any visible damage and found none. I replaced the LCD with a known working unit—and there"s still no backlight on the iPad. What else could be wrong?

As I reflect on my disassembly procedure, I have considered that I did something differently the second time around. The first time, I used a plastic scribe to release the LCD cable from the logic board. The second time around, I used the mini screwdriver from the kit to pop up the retainer. Reflecting on my actions, and knowing better, using the screwdriver probably created a short across contacts and damaged the logic board, despite my working carefully. Of course, I am just guessing—but that was a difference between the two repairs I did. The first iPad repair being successful—the second, not so successful.

Note: If your MacBook Pro has any damage which impairs the service, that issue will need to be repaired first. In some cases, there may be a cost associated with the repair.

If you ended up on this page doing normal allowed operations, please contact our support at support@mdpi.com. Please include what you were doing when this page came up and the Ray ID & Your IP found at the

An import function allows additionally to use Windows fonts. With the FontEditor it is easy to generate for example Cyrillic, Greek and Arabic fonts. The preview function shows immediately the size and style in simulation window. When the testboard EA 9780-2USB is connected to the USB port, you can see the character (or any predefined text) live on the display which is plugged-in!

It also features a new LCD backlight for superior visibility, and natural display shows expressions and results exactly as they would appear in a textbook.

It was also stated that the larger iPhone 6 could be the only model to obtain the possible LCD backlight, 128 GB storage and sapphire crystal display.

The new plant in CTSP will mainly develop four products including LCD backlight module substrates, high-level functional films, materials for solar modules, and green energy-saving materials such as anti- UV / IR energy-saving films and IMD mold polychrome film.

Fully customizable LCD controller with the ability to drive different display panels regardless of interface, resolution or manufacturer; LCD controller supporting timing generation, color space conversion and alpha blending; LCD backlight control; and Hardware acceleration using FPGA fabric, providing tight integration of processor system and programmable logic.

The special LCD backlight adjustment delivers a dynamic depth of color and deeper details that result in intense expression of every shade and hue of color you see on your screen.

Dooda"s main business consists of the R&D, production and sales of the dual-use of LED backlight and lighting technology in both military and civil market sector; while CGE engages inR&D, production and sales of various series of the civil and military dual-application of LED and LCD backlight power supply, built-in power supply related optoelectronic products, electronic devices and provision of related technical services.

A large, angled LCD backlight display ensures that digits are easy to see at all times, and a two-colour ink roller provides rapid print speeds of 2.3 lines per second.

Sampling of those include fluorescence modeling for life sciences, photorealistic rendering for accurate visualization of illumination designs and enhanced modeling of 3D surface textures utilized in the design of LCD backlight displays, projection systems, lightpipes and microarrays.

The wide range of conditions over which LCD monitors are used means that it is desirable to produce displays whose luminance (brightness) can be altered to match both bright and dim environments. This allows a user to set the screen to a comfortable level of brightness depending on their working conditions and ambient lighting. Manufacturers will normally quote a maximum brightness figure in their display specification, but it is also important to consider the lower range of adjustments possible from the screen as you would probably never want to use it at its highest setting. Indeed with specs often ranging up to 500 cd/m2, you will certainly need to use the screen at something a little less harsh on the eyes. As a reminder, we test the full range of backlight adjustments and the corresponding brightness values during each of our reviews. During our calibration process as well we try to adjust the screen to a setting of 120 cd/m2 which is considered the recommended luminance for an LCD monitor in normal lighting conditions. This process helps to give you an idea of what adjustments you need to make to the screen in order to return a luminance which you might actually want to use day to day.

Changing the display luminance is achieved by reducing the total light output for both CCFL- and LED-based backlights. By far the most prevalent technique for dimming the backlight is called Pulse Width Modulation (PWM), which has been in use for many years in desktop and laptop displays. However, this technique is not without some issues and the introduction of displays with high brightness levels and the popularisation of LED backlights has made the side-effects of PWM more visible than before, and in some cases may be a source of visible flicker, eyestrain, eye fatigue, headaches and other associated issues for people sensitive to it. This article is not intended to alarm, but is intended to show how PWM works and why it is used, as well as how to test a display to see its effects more clearly. We will also take a look at the methods some manufacturers are now adopting to address these concerns and provide flicker-free backlights instead. As awareness grows, more and more manufacturers are focusing on eye health with their monitor ranges.

Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) is one method of reducing the perceived luminance in displays, which it achieves by cycling the backlight on and off very rapidly, at a frequency you can’t necessary detect with the naked eye, but which could lead to eye issues, headaches etc. This method generally means that at 100% brightness a constant voltage is applied to the backlight and it is continuously lit. As you lower the brightness control the perceived luminance for the user reduces due to a number of possible controlling factors:

1) Frequency –The backlight is cycled on and off very rapidly, and this cycling typically occurs at a fixed frequency (in Hz). How fast this cycling occurs can impact whether flicker is visible or perceivable to the user, with higher frequencies being potentially less problematic. PWM has been known to operate at low frequencies of 180 – 240Hz for example which are likely to be more problematic than higher frequencies ranging up in to the Kilohertz range (e.g. 18,000Hz).

2) Modulation –The modulation of the cycling has an impact on the perceived brightness, and this describes the difference between the luminance in an “on” and in an “off” state. In some examples the backlight is completely turned off during the cycle so it is literally being turned on/off rapidly across the full brightness adjustment range. In those examples the luminance output is controlled really by the duty cycle only (see point 3). In other examples the backlight is not always being completely turned off but rather the voltage applied to the backlight is being rapidly alternated, resulting in less extreme differences between the on and off states. Often this modulation will be narrow in the high brightness range of the display, but as you reduce further, the modulation becomes wider until it reaches a point where the backlight is being switched completely off. From there, the change in the duty cycle (point 3) controls the further changes in the luminance output.

3) Duty Cycle – The fraction of each cycle for which the backlight is in an “on” state is called the duty cycle. By altering this duty cycle the total light output of the backlight can be changed. As you reduce the brightness to reach a lower luminance, the duty cycle becomes progressively shorter, and the time for which the backlight is on becomes shorter, while the time for which it is off is longer. This technique works visually since cycling the backlight on and off sufficiently fast means the user cannot see this flickering, because it lies above their flicker-fusion threshold (more on this later).

Above we can see graphs of a backlight’s output using “ideal” PWM for several cycles. The maximum output of this backlight in the example is 100 cd/m2, and the perceived luminance for the 90%, 50% and 10% cases are: 90, 50 and 10 cd/m2 respectively. The modulation percentage is the ratio between the minimum and maximum luminance during the cycle, and is 100% here, so it is being completely turned on and off. Note that during the duty cycle the backlight is at its maximum luminance.

The analogue (non-PWM) graphs corresponding to these perceived luminance levels would appear as shown below. In this case there is no modulation. This is the method used for flicker-free backlights which we will discuss more a little later.

The main reasons for the use of PWM is that it is simple to implement, requiring only that the backlight can be switched on and off rapidly, and also gives a large range of possible luminance.

CCFL backlights can be dimmed by reducing the current through the bulb, but only by about a factor of 2 because of their strict current and voltage requirements. This leaves PWM as the only simple method of achieving a large range of luminance. A CCFL bulb is in fact normally driven by the inverter to cycle on and off at a rate in the 10’s of kilohertz and well outside the range of flicker visible to humans. However, the PWM cycling typically occurs at a much lower frequency, around 175Hz, which can produce artefacts visible to humans.

The luminance of LED backlights can be adjusted greatly by altering the current passing through them, though this has the effect of altering the colour temperature slightly. This analogue approach to LED luminance is also undesirable since the accompanying circuits must take into account the heat generated by the LED’s. LED’s heat up when on, which reduces their resistance and further increases the current flowing through them. This can quickly lead to runaway current use in very high-brightness LED’s and cause them to burn out. Using PWM the current can be forced to hold a constant value during the duty cycle, meaning the colour temperature is always the same and current overloads are not a problem.

While PWM is attractive to hardware makers for the reasons outlined above, it can also introduce distracting visual effects if not used carefully. Flicker from LED backlights is typically much more visible than for older CCFL backlights at the same duty cycle because the LED’s are able to switch on and off much faster, and do not continue to “glow” after the power is cut off. This means that where the CCFL backlight showed rather smooth luminance variation, the LED version shows sharper transitions between on and off states. This is why more recently the subject of PWM has cropped up online and in reviews, since more and more displays are moving to W-LED backlighting units now.

Where the effect of flicker can really come into play is any time the user’s eyes are moving. Under constant illumination with no flickering (e.g. sunlight) the image is smoothly blurred and is how we normally perceive motion. However, when combined with a light source using PWM several discrete afterimages of the screen may be perceived simultaneously and reduce readability and the ability of the eyes to lock onto objects. From the earlier analysis of the CCFL backlighting we know that false colour may be introduced as well, even when the original image is monochromatic. Below are shown examples of how text might appear while the eyes are moving horizontally under different backlights.

It is important to remember that this is entirely due to the backlight, and the display itself is showing a static image. Often it is said that humans cannot see more than 24 frames per second (fps), which is not true and actually corresponds to the approximate frame rate needed to perceive continuous motion. In fact, while the eyes are moving (such as when reading) it is possible to see the effects of flicker at several hundred hertz. The ability to observe flicker varies greatly between individuals, and even depends on where a user is looking since peripheral vision is most sensitive.

So how fast is PWM cycling backlights on and off? This seems to depend on the backlight type used, with CCFL-based backlights nearly all cycling at 175Hz or 175 times per second. LED backlights have been reported typically running from 180 – 420Hz, with those at the lower end flickering much more visibly. Some have even faster frequencies of >2000Hz so it really can vary. While this might seem too fast to be visible, keep in mind that 175Hz is not much faster than the 100-120Hz flicker observed in lights connected directly to the mains power.

100-120Hz flickering of fluorescent lights has in fact been linked to symptoms such as severe eye strain and headaches in a portion of the population, which is why high-frequency ballast circuits were developed that provide almost continuous output. Using PWM at low frequencies negates the advantages of using these better ballasts in backlights because it turns an almost constant light source back into one that flickers. An additional consideration is that poor quality or defective ballasts in fluorescent backlights can produce audible noise. In many cases this is exacerbated when PWM is introduced since the electronics are now dealing with an additional frequency at which power usage is changing.

It is also important to distinguish the difference between flicker in CRT displays and CCFL and LED backlit TFT displays. While a CRT may flicker as low as 60Hz, only a small strip is illuminated at any time as the electron gun scans from top to bottom. With CCFL and LED backlit TFT displays the entire screen surface illuminates at once, meaning much more light is emitted over a short time. This can be more distracting than in CRTs in some cases, especially if short duty cycles are used.

The flicker itself in display backlights may be subtle and not easily perceptible for some people, but the natural variation in human vision seems to make it clearly visible to others. With the use of high-brightness LED’s on the rise it is becoming increasingly necessary to use short PWM duty cycles to control brightness, making flicker more of a problem. With users spending many hours every day looking at their monitors, shouldn’t we consider the long term effects of both perceptible and imperceptible flicker?

If you find PWM backlight flickering distracting or just want to see if reducing it makes reading on a monitor easier, I’d encourage you to try the following: Turn the brightness of your monitor up to maximum and disable any automatic brightness adjustments. Now use the colour correction available in your video card drivers or calibration device to reduce the brightness to normal levels (usually by adjusting the contrast slider). This will reduce the luminance and contrast of your monitor while leaving the backlight on as much as possible during PWM cycles. While not a long-term solution for most due to the decreased contrast, this technique can help to discover if a reduction in PWM usage is helpful.

A much better method of course would be to purchase a display not relying on PWM for dimming, or at least one which uses a much higher cycling frequency. Few manufacturers seem to have implemented PWM at frequencies that would limit visible artefacts (well above 500Hz for CCFL and above 2000 Hz for LED). Additionally, some displays using PWM do not use a 100% duty cycle even at full brightness, meaning they will always produce flicker. Several LED-based displays may in fact be currently available which do not use PWM, but until backlight frequency and modulation become listed in specifications it will be necessary to see the display in person. Some manufacturers promote “flicker free” monitors in their range (BenQ, Acer for example) which are designed to not use PWM at all and instead use a Direct Current (DC) method of backlight dimming. Other manufacturers such as Eizo talk about flicker free backlights but also list a hybrid solution for their backlight dimming, where PWM is used for some of the brightness adjustment range at the lower end. In fact it seems an increasingly common practice for a screen to be PWM free down to a certain point, and then fro PWM to be used to really drive down the minimum luminance from there.

An easy method of measuring the PWM frequency of a backlight would be ideal, and luckily it can be done using only a camera which allows manual control of the shutter speed. This can quickly and easily identify PWM frequencies in the lower range, but may not be suitable for high frequency PWM. It should be able to detect PWM up to at least 500Hz though, but anything above that may look like a solid block, suggesting no use of PWM, when in fact it might be just using a higher frequency. Further more complex methods such as our oscilloscope setup would be needed to validate flicker-free status for definite.

(Optional) Set the camera white balance by getting a reading off the screen while displaying only white. If not possible, then manually set the white balance to about 6000K.

Display a single vertical thin white line on a black background on the monitor (1-3 pixels wide should be fine). The image should be the only thing visible. Here is an example you may wish to save and use, show it full screen on your monitor.

Set the camera to use a shutter speed of 1/2 to 1/25 of a second. You may need to set the ISO sensitivity and aperture in order to capture enough light. Make sure the line is in focus at the distance you are holding it (lock the focus if needed).

Multiply this count by the inverse of the shutter speed. For example, if using a shutter speed of 1/25 of a second and 7 cycles are counted, then the number of cycles per second is 25 * 7 = 175Hz. This is the backlight cycle frequency.

What we are doing with this technique is turning a temporal effect into a spatial one by moving the camera during capture. The only significant source of light during the image capture is the thin line on the display, which is exposed onto consecutive columns on the sensor. If the backlight is flickering, different columns will have different brightness or colour values determined by the backlight at the time it was exposed.

A common problem when first attempting this technique is that the image is too dark. This can be mitigated by using a larger camera aperture (lower f/number) or increasing the ISO value. The shutter speed is not a factor in the exposure since we are using it only to control the total exposure time. The brightness of the image can also be adjusted by changing the speed at which the camera is moved, with a fast speed giving a darker image and more temporal resolution and a slow speed a brighter image with lower resolution. Another problem encountered is unevenly-spaced cycles in the final image, which is caused by the camera changing speed during exposure. Continuing to move the camera before and after the exposure helps to steady this. An image which looks particularly smooth may be due to it being out of focus. This can sometimes be helped by pressing the shutter button halfway to focus on the line target, then proceeding as normal.

Depending on the monitor several additional effects may be visible. CCFL-based backlights often show different colours at the start and end of each cycle, which means the phosphors used respond at different rates. LED-based backlights often use a higher cycling frequency than CCFL-based, and more rapid camera movement may be needed to easily see them. Dark stripes between cycles mean that the PWM duty cycle has been reduced to such an extent that no light is emitted for part of the cycles.

Using our oscilloscope and photosensor equipment it is possible to measure the PWM frequency and patterns far more accurately. While the above photo method is certainly suitable for a casual user, an oscilloscope can reveal more detail about the PWM operation and will be featured in all our reviews moving forward. We measure the luminance output of the screen at brightness settings of 100, 50 and 0%. This allows us to easily identify the backlight dimming technique, and if PWM is being used we can work out its frequency and comment on modulation, duty cycle etc.

Asus PA248Q – W-LED backlight. At 100% brightness we see a constant luminance output and a straight line, as there is no need for the backlight to be cycled. At 50% you can see PWM controls the backlight on and off. The modulation is always 100%, but the luminance reduction is controlled by the duty cycle which becomes progressively shorter. You can see much shorter “on” peaks in the 0% brightness graphs. We measure the frequency at 180Hz which is fairly typical.

BenQ GW2760HS – W-LED backlight. At all brightness settings the luminance output is a flat line, showing no PWM is being used. This is part of BenQ’s flicker free range.

The oscilloscope graphs can also allow us to examine the behaviour of the luminance output. Above is a typical W-LED backlight dimmed to 0% where PWM is used. You can see the changes between on and off are very steep and sudden, as the LED backlight is able to turn on and off very rapidly. As we’ve already discussed this can lead to potentially more noticeable flicker and associated issues as the changes are more pronounced.

The oscillographs for a typical CCFL display using PWM at 0% looks like the above. You can see the transitions from on to off are less sudden as the phosphors don’t go dark as quickly as with LED backlight units. As a result, the use of PWM may be less problematic to users.

As we said at the beginning, this article is not designed to scare people away from modern LCD displays, rather to help inform people of this potential issue. With the growing popularity in W-LED backlit monitors it does seem to be causing more user complaints than older displays, and this is related to the PWM technique used and ultimately the type of backlight selected. Of course the problems which can potentially be caused by the use of PWM are not seen by everyone, and in fact I expect there are far more people who would never notice any of the symptoms than there are people who do. For those who do suffer from side effects including headaches and eye strain there is an explanation at least.

With the long term and proven success of a technology like Pulse Width Modulation, and the many years of use in CCFL displays we can’t see it being widely changed at any time soon to be honest, even with the popular move to W-LED backlit units. It is still a reliable method for controlling the backlight intensity and therefore offering a range of brightness adjustments which every user would want and need. Those who are concerned about its side effects or who have had problems with previous displays should try and consider the frequency of the PWM in their new display, or perhaps even try and find a screen where it is not used at all in backlight dimming. Some manufacturers are proactively addressing this concern through the use of flicker free backlights, and so options are emerging which do not use PWM.

To evaluate the performance of display devices, several metrics are commonly used, such as response time, CR, color gamut, panel flexibility, viewing angle, resolution density, peak brightness, lifetime, among others. Here we compare LCD and OLED devices based on these metrics one by one.

where Tf is the frame time (e.g., Tf=16.67 ms for 60 fps). Using this equation, we can easily obtain an MPRT as long as the LC response time and TFT frame rate are known. The results are plotted in Figure 5.

From Figure 5, we can gain several important physical insights: (1) Increasing the frame rate is a simple approach to suppress image motion blur, but its improvement gradually saturates. For example, if the LC response time is 10 ms, then increasing the frame rate from 30 to 60 fps would significantly reduce the MPRT. However, as the TFT frame rate continues to increase to 120 and 240 fps, then the improvement gradually saturates. (2) At a given frame rate, say 120 fps, as the LC response time decreases, the MPRT decreases almost linearly and then saturates. This means that the MPRT is mainly determined by the TFT frame rate once the LC response time is fast enough, i.e., τ≪Tf. Under such conditions, Equation (1) is reduced to MPRT≈0.8Tf. (3) When the LC response is <2 ms, its MPRT is comparable to that of an OLED at the same frame rate, e.g., 120 fps. Here we assume the OLED’s response time is 0.

The last finding is somehow counter to the intuition that a LCD should have a more severe motion picture image blur, as its response time is approximately 1000 × slower than that of an OLED (ms vs. μs). To validate this prediction, Chen et al.

If we want to further suppress image blur to an unnoticeable level (MPRT<2 ms), decreasing the duty ratio (for LCDs, this is the on-time ratio of the backlight, called scanning backlight or blinking backlight) is mostly adopted

As Figure 6 depicts, there are two types of surface reflections. The first one is from a direct light source, i.e., the sun or a light bulb, denoted as A1. Its reflection is fairly specular, and in practice, we can avoid this reflection (i.e., strong glare from direct sun) by simply adjusting the display position or viewing direction. However, the second reflection, denoted as A2, is quite difficult to avoid. It comes from an extended background light source, such as a clear sky or scattered ceiling light. In our analysis, we mainly focus on the second reflection (A2).

To investigate the ACR, we have to clarify the reflectance first. A large TV is often operated by remote control, so touchscreen functionality is not required. As a result, an anti-reflection coating is commonly adopted. Let us assume that the reflectance is 1.2% for both LCD and OLED TVs. For the peak brightness and CR, different TV makers have their own specifications. Here, without losing generality, let us use the following brands as examples for comparison: LCD peak brightness=1200 nits, LCD CR=5000:1 (Sony 75″ X940E LCD TV); OLED peak brightness=600 nits, and OLED CR=infinity (Sony 77″ A1E OLED TV). The obtained ACR for both LCD and OLED TVs is plotted in Figure 7a. As expected, OLEDs have a much higher ACR in the low illuminance region (dark room) but drop sharply as ambient light gets brighter. At 63 lux, OLEDs have the same ACR as LCDs. Beyond 63 lux, LCDs take over. In many countries, 60 lux is the typical lighting condition in a family living room. This implies that LCDs have a higher ACR when the ambient light is brighter than 60 lux, such as in office lighting (320–500 lux) and a living room with the window shades or curtain open. Please note that, in our simulation, we used the real peak brightness of LCDs (1200 nits) and OLEDs (600 nits). In most cases, the displayed contents could vary from black to white. If we consider a typical 50% average picture level (i.e., 600 nits for LCDs vs. 300 nits for OLEDs), then the crossover point drops to 31 lux (not shown here), and LCDs are even more favorable. This is because the on-state brightness plays an important role to the ACR, as Equation (2) shows.

Calculated ACR as a function of different ambient light conditions for LCD and OLED TVs. Here we assume that the LCD peak brightness is 1200 nits and OLED peak brightness is 600 nits, with a surface reflectance of 1.2% for both the LCD and OLED. (a) LCD CR: 5000:1, OLED CR: infinity; (b) LCD CR: 20 000:1, OLED CR: infinity.

Recently, an LCD panel with an in-cell polarizer was proposed to decouple the depolarization effect of the LC layer and color filtersFigure 7b. Now, the crossover point takes place at 16 lux, which continues to favor LCDs.

For mobile displays, such as smartphones, touch functionality is required. Thus the outer surface is often subject to fingerprints, grease and other contaminants. Therefore, only a simple grade AR coating is used, and the total surface reflectance amounts to ~4.4%. Let us use the FFS LCD as an example for comparison with an OLED. The following parameters are used in our simulations: the LCD peak brightness is 600 nits and CR is 2000:1, while the OLED peak brightness is 500 nits and CR is infinity. Figure 8a depicts the calculated results, where the intersection occurs at 107 lux, which corresponds to a very dark overcast day. If the newly proposed structure with an in-cell polarizer is used, the FFS LCD could attain a 3000:1 CRFigure 8b), corresponding to an office building hallway or restroom lighting. For reference, a typical office light is in the range of 320–500 luxFigure 8 depicts, OLEDs have a superior ACR under dark ambient conditions, but this advantage gradually diminishes as the ambient light increases. This was indeed experimentally confirmed by LG Display

Calculated ACR as a function of different ambient light conditions for LCD and OLED smartphones. Reflectance is assumed to be 4.4% for both LCD and OLED. (a) LCD CR: 2000:1, OLED CR: infinity; (b) LCD CR: 3000:1, OLED CR: infinity. (LCD peak brightness: 600 nits; OLED peak brightness: 500 nits).

For conventional LCDs employing a WLED backlight, the yellow spectrum generated by YAG (yttrium aluminum garnet) phosphor is too broad to become highly saturated RGB primary colors, as shown in Figure 9aTable 2. The first choice is the RG-phosphor-converted WLEDFigure 9b, the red and green emission spectra are well separated; still, the green spectrum (generated by β-sialon:Eu2+ phosphor) is fairly broad and red spectrum (generated by K2SiF6:Mn4+ (potassium silicofluoride, KSF) phosphor) is not deep enough, leading to 70%–80% Rec. 2020, depending on the color filters used.

A QD-enhanced backlight (e.g., quantum dot enhancement film, QDEF) offers another option for a wide color gamutFigure 9c), so that high purity RGB colors can be realized and a color gamut of ~90% Rec. 2020 can be achieved. One safety concern is that some high-performance QDs contain the heavy metal Cd. To be compatible with the restriction of hazardous substances, the maximum cadmium content should be under 100 ppm in any consumer electronic product

Recently, a new LED technology, called the Vivid Color LED, was demonstratedFigure 9d), which leads to an unprecedented color gamut (~98% Rec. 2020) together with specially designed color filters. Such a color gamut is comparable to that of laser-lit displays but without laser speckles. Moreover, the Vivid Color LED is heavy-metal free and shows good thermal stability. If the efficiency and cost can be further improved, it would be a perfect candidate for an LCD backlight.

A color filter array is another effective approach to enhance the color gamut of an OLED. For example, in 2017, AUO demonstrated a 5-inch top-emission OLED panel with 95% Rec. 2020. In this design, so-called symmetric panel stacking with a color filter is employed to generate purer RGB primary colors

As mentioned earlier, TFT LCDs are a fairly mature technology. They can be operated for >10 years without noticeable performance degradation. However, OLEDs are more sensitive to moisture and oxygen than LCDs. Thus their lifetime, especially for blue OLEDs, is still an issue. For mobile displays, this is not a critical issue because the expected usage of a smartphone is approximately 2–3 years. However, for large TVs, a lifetime of >30 000 h (>10 years) has become the normal expectation for consumers.

Here we focus on two types of lifetime: storage and operational. To enable a 10-year storage lifetime, according to the analysis−6 g (m2-day)−1 and 1 × 10−5 cm3 (m2-day)−1, respectively. To achieve these values, organic and/or inorganic thin films have been developed to effectively protect the OLED and lengthen its storage lifetime. Meanwhile, it is compatible to flexible substrates and favors a thinner display profile

Power consumption is equally important as other metrics. For LCDs, power consumption consists of two parts: the backlight and driving electronics. The ratio between these two depends on the display size and resolution density. For a 55″ 4K LCD TV, the backlight occupies approximately 90% of the total power consumption. To make full use of the backlight, a dual brightness enhancement film is commonly embedded to recycle mismatched polarized light

The power efficiency of an OLED is generally limited by the extraction efficiency (ηext~20%). To improve the power efficiency, multiple approaches can be used, such as a microlens array, a corrugated structure with a high refractive index substrateFigure 11 shows the power efficiencies of white, green, red and blue phosphorescent as well as blue fluorescent/TTF OLEDs over time. For OLEDs with fluorescent emitters in the 1980s and 1990s, the power efficiency was limited by the IQE, typically <10 lm W−1(Refs. 41, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118). With the incorporation of phosphorescent emitters in the ~2000 s, the power efficiency was significantly improved owing to the materials and device engineering−1 was demonstrated in 2011 (Ref. 127), which showed a >100 × improvement compared with that of the basic two-layer device proposed in 1987 (1.5 lm W−1 in Ref. 41). A white OLED with a power efficiency >100 lm W−1 was also demonstrated, which was comparable to the power efficiency of a LCD backlight. For red and blue OLEDs, their power efficiencies are generally lower than that of the green OLED due to their lower photopic sensitivity function, and there is a tradeoff between color saturation and power efficiency. Note, we separated the performances of blue phosphorescent and fluorescent/TTF OLEDs. For the blue phosphorescent OLEDs, although the power efficiency can be as high as ~80 lm W−1, the operation lifetime is short and color is sky-blue. For display applications, the blue TTF OLED is the favored choice, with an acceptable lifetime and color but a much lower power efficiency (16 lm W−1) than its phosphorescent counterpartFigure 11 shows.

To compare the power consumption of LCDs and OLEDs with the same resolution density, the displayed contents should be considered as well. In general, OLEDs are more efficient than LCDs for displaying dark images because black pixels consume little power for an emissive display, while LCDs are more efficient than OLEDs at displaying bright images. Currently, a ~65% average picture level is the intersection point between RGB OLEDs and LCDs

Flexible displays have a long history and have been attempted by many companies, but this technology has only recently begun to see commercial implementations for consumer electronics

In addition to the aforementioned six display metrics, other parameters are equally important. For example, high-resolution density has become a standard for all high-end display devices. Currently, LCD is taking the lead in consumer electronic products. Eight-hundred ppi or even >1000 ppi LCDs have already been demonstrated and commercialized, such as in the Sony 5.5″ 4k Smartphone Xperia Z5 Premium. The resolution of RGB OLEDs is limited by the physical dimension of the fine-pitch shadow mask. To compete with LCDs, most OLED displays use the PenTile RGB subpixel matrix scheme

The viewing angle is another important property that defines the viewing experience at large oblique angles, which is quite critical for multi-viewer applications. OLEDs are self-emissive and have an angular distribution that is much broader than that of LCDs. For instance, at a 30° viewing angle, the OLED brightness only decreases by 30%, whereas the LCD brightness decrease exceeds 50%. To widen an LCD’s viewing angle, three options can be used. (1) Remove the brightness-enhancement film in the backlight system. The tradeoff is decreased on-axis brightness

In addition to brightness, color, grayscale and the CR also vary with the viewing angle, known as color shift and gamma shift. In these aspects, LCDs and OLEDs have different mechanisms. For LCDs, they are induced by the anisotropic property of the LC material, which could be compensated for with uniaxial or biaxial films

Cost is another key factor for consumers. LCDs have been the topic of extensive investigation and investment, whereas OLED technology is emerging and its fabrication yield and capability are still far behind LCDs. As a result, the price of OLEDs is about twice as high as that of LCDs, especially for large displays. As more investment is made in OLEDs and more advanced fabrication technology is developed, such as ink-jet printing

LED LCD backlights are small light strips, or light sources, contained inside a display, TV, or monitor to provide lighting for the screen. All LED TVs are LCD panels with LED backlighting. A common misconception is that LED displays are different from LCD when fundamentally they are the same. LED is better described as a sub-set of LCD devices.

LCD is an acronym for Liquid Crystal Display, which is a type of monitor or screen—and flat-panel technology—that relies on thousands or millions of pixels, arranged in a rectangular grid. When an LCD is turned on, each pixel takes on a red, green, or blue sub-pixel (RGB) that is either enabled or disabled. When the pixels are off, the individual section appears black, and when all of the sub-pixels are on, it appears white. Collectively, the arranged pixels provide the sharp image on the display by being in either an on or off configuration.

The LED backlight illuminates the pixels, from behind, making them appear richer and brighter. Not all LCDs have a backlight, and for those that do, not all of them utilize LED backlighting. Some displays also use CCFL lighting or Cold-Cathode Fluorescent Lamps. Although, it should be noted that CCFL displays are being phased out in favor of LED-backlit panels.

The liquid crystals inside an LCD panel don’t have any illumination on their own and require the light to come from a separate component, which, in this case, is provided by the LED backlighting.

Older display types, such as cathode ray tubes (CRT) produce illumination already and so they do not need an additional light source like LCD devices.

While it can be confusing at first, LED-backlit panels are different from a full LED. LED-backlit panels have LED strips lining the edges of the screen whereas full HD illuminates the entirety of the display often with higher brightness and color accuracy. Full LED panels achieve this thanks to an evenly distributed light source across the rear of the set.

This changes the picture on the display, particularly when it comes to dark scenes and true black colors. On an LED-backlit display, for example, dark scenes may appear washed out because of how the light is focused on the edges and spreads thinly into the center.

Because both types are fundamentally LCD panels, both LED and LED-backlit displays produce bright and vivid pictures. However, scenes may appear brighter or slightly washed out, depending on how the light source is distributed, such as from edge backlighting versus evenly distributed lighting. If you prefer a more accurate picture, full LED panels are the way to go, but they are more expensive.

Similar to TVs and other displays, an LED-backlit LCD monitor is an LCD panel with LED backlights. What often sets a monitor or computer monitor apart from standard displays is they don’t include a built-in tuner, which is needed to access cable. They often include different video or display ports, such as HDMI, DisplayPort, VGA, and so on. They"re designed to be used as a primary or secondary display for desktop computers, laptops, and beyond.

LED-backlit TVs, monitors, and displays are used in many different places including ATMs, cash registers, digital billboards, fitness equipment like treadmills, vehicle infotainment systems, gas station pumps, Pachinko, and casino machines, mobile devices, and much more.

If you want to replace your TV or computer screen, you should check with the manufacturer to see if they offer repair services. If not, try Best Buy or another electronics repair shop.

While all LED TVs are LCD TVs, not all LCD TVs are LED TVs. If a TV is marketed as LCD with no mention of LED, then it probably uses a different type of backlighting such as CCFL.

When the screen is sleeping for a while, it would be nice to turn the backlight off, and have it go back to the saved brighness when the screen is touched, and the system returns from sleep.

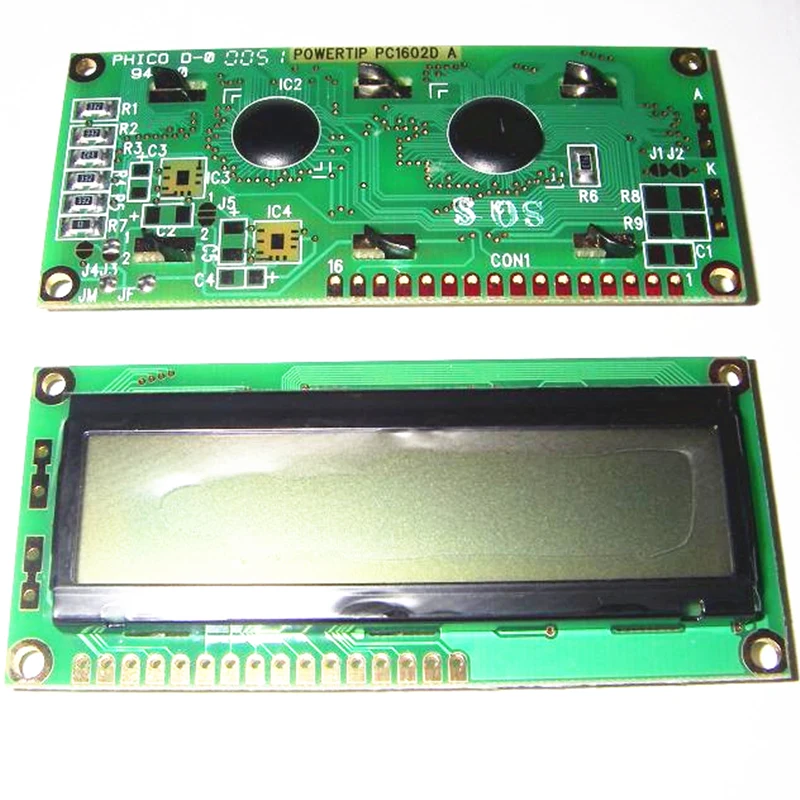

This 16-character, 2-line parallel liquid crystal display achieves a large viewing area in a compact package. It features a yellow-green LED backlight and uses the common HD44780 interface (330k pdf), so sample interface code is widely available for a variety of microcontrollers. This LCD is also available without a backlight.

As shown in the diagram above, a potentiometer whose output is connected to Vo will allow you to set the contrast for optimal viewing of your display.

The backlight in this LCD is composed of LEDs in series. The total voltage drop across these LEDs is typically 4.2 V and the recommended current through the LEDs is 120 mA. You should use a current limiting resistor RLIMIT as shown above where:

In the diagram above, VBACKLIGHT is shown as 5 V, but you are not restricted to 5 V; any voltage above the diode-drop voltage will work as long as you choose the appropriate value for your current-limiting resistor. You can also use a PWM-controlled MOSFET to achieve variable dimming of the backlight if so desired.

Note: No cables or connectors are included with this product, but a 40×2-pin 0.100" male header strip and 20", 16-conductor ribbon cable can be purchased separately. You can break a 7×2 segment from the header strip and solder it to the 14 through-holes on the left side of the LCD PCB; the ribbon cable will then plug into the header pins (leaving two holes empty). The header pins won’t enforce proper orientation of the cable, so you will need to take care to plug it into the correct pins. The 8×2 shrouded box header can be used with this LCD if you use pliers to pull out connector pins 15 and 16, effectively turning it into a 7×2 keyed receptacle for a 16-conductor ribbon cable.

Dr Pan: Hello, Greg. LED backlight is the light source for LCD screen since it can’t emit light by itself. It is an optical component and non-standard product which is attached to the back of LCD. LED backlight can also be used as a separate lighting device. For example: backlight keyboard, smart lighting socket and currently fashionable backlight capacitive switch.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey