liquid crystal display screens quotation

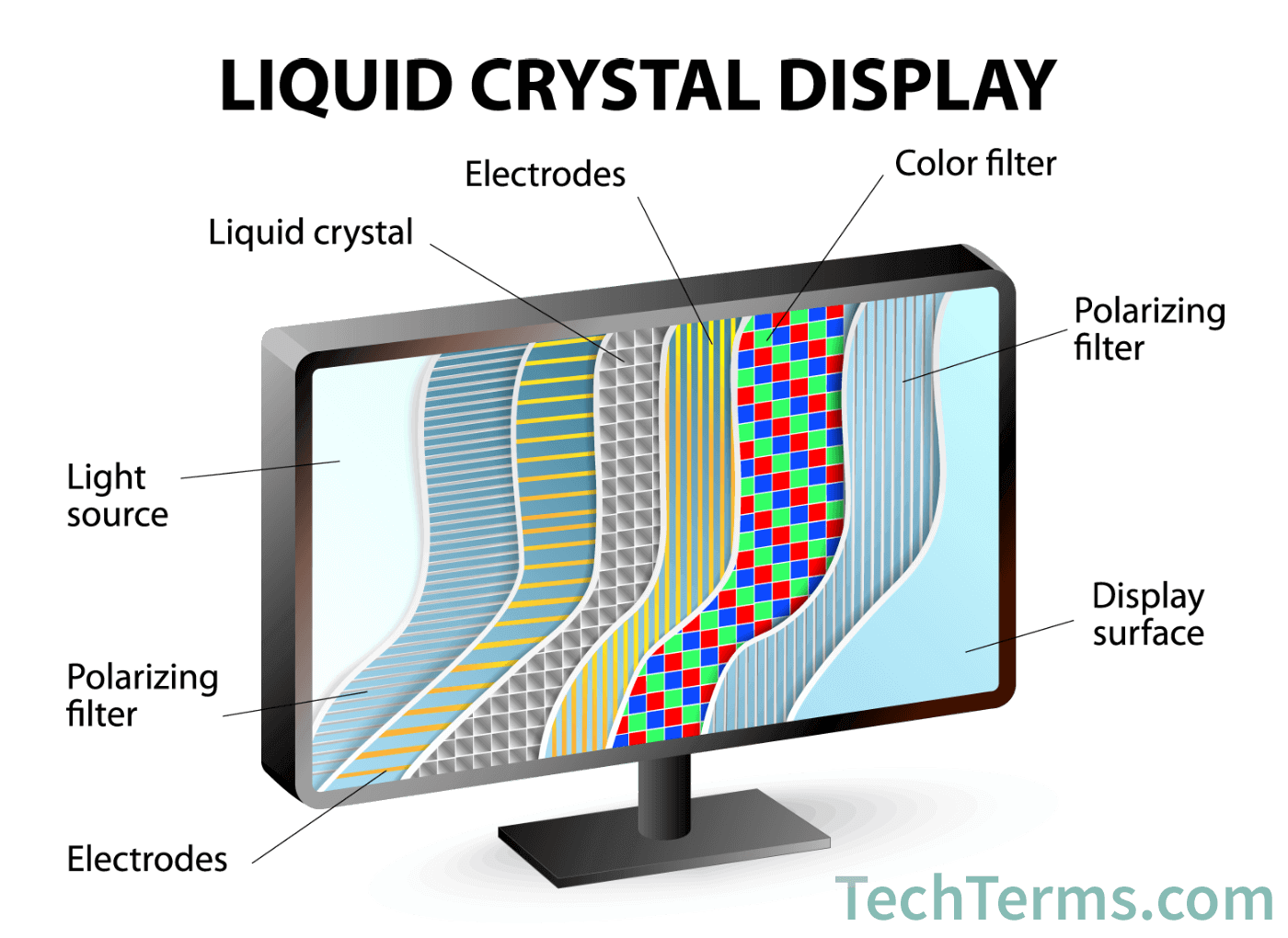

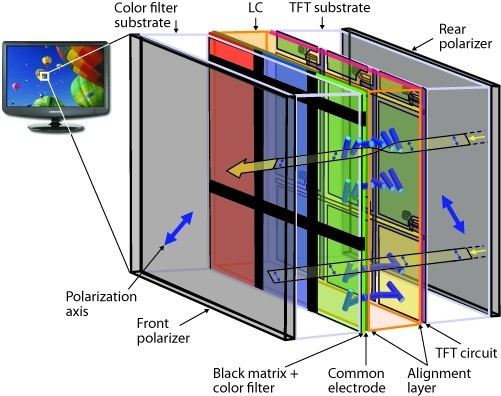

Liquid crystal display (LCD) is a flat panel display that uses the light modulating properties of liquid crystals. Liquid crystals do not produce light directly, instead using a backlight or reflector to produce images in colour or monochrome.

Manufacturer of custom rugged displays for military, marine, industrial, avionic, medical, transportation, commercial and other applications. Diverse engineering team is able to design to fit any enclosure. Features include sunlight readable, NVIS, waterproof, flip-up, flip-down, rack mount drawer, panel or rack mount, and much more. All sizes are available from small to large. Suitable for workstations, cockpits, medical devices and other safety- or mission-critical applications. Manufactured, serviced, and supported in the USA.

PG Technologies supplies Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) Technology to a variety of industries. Using the latest production processes, our manufacturing facility has developed a wide range of products capable of meeting today’s market demands.

LCD displays are divided into many types, such as TN LCD, IPS LCD, high-brightness LCD, etc. The prices of LCD LCDs with different specifications are entirely different, so that LCD LCD manufacturers will quote the required specifications of the LCD LCD display.

LCD liquid crystal display mainly comprises several key raw materials of LCD liquid crystal display glass panel, backlight, IC, and FPC. Each raw material has different specifications and qualities, which will directly affect the price of LCD display. Take the backlight as an example. The price of LED lamp beads can vary from 5 to 15 yuan. The number of lamp beads, ordinary lamp beads, or dual-core lamps has a price difference. These will directly affect the LCD liquid crystal display cost and thus affect the price.

Different LCD liquid crystal display application industries will have different solutions. Customers need to choose different raw materials according to different solutions, and the corresponding LCD liquid crystal display prices will vary. For example, Proculus Technologies will provide corresponding solutions according to the different industries in the smart terminal.

The factors affecting the price of LCD display are summarized above. In addition to the price of LCD screens, which are more concerned by customers, it is also important to find strong LCD screen manufacturers. Proculus Technologies focuses on providing standard and customized display products and displays technology solutions, which are trustworthy. Before buying an LCD screen, give priority to Proculus!

A liquid-crystal display (LCD) is a flat-panel display or other electronically modulated optical device that uses the light-modulating properties of liquid crystals combined with polarizers. Liquid crystals do not emit light directlybacklight or reflector to produce images in color or monochrome.seven-segment displays, as in a digital clock, are all good examples of devices with these displays. They use the same basic technology, except that arbitrary images are made from a matrix of small pixels, while other displays have larger elements. LCDs can either be normally on (positive) or off (negative), depending on the polarizer arrangement. For example, a character positive LCD with a backlight will have black lettering on a background that is the color of the backlight, and a character negative LCD will have a black background with the letters being of the same color as the backlight. Optical filters are added to white on blue LCDs to give them their characteristic appearance.

LCDs are used in a wide range of applications, including LCD televisions, computer monitors, instrument panels, aircraft cockpit displays, and indoor and outdoor signage. Small LCD screens are common in LCD projectors and portable consumer devices such as digital cameras, watches, calculators, and mobile telephones, including smartphones. LCD screens have replaced heavy, bulky and less energy-efficient cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays in nearly all applications. The phosphors used in CRTs make them vulnerable to image burn-in when a static image is displayed on a screen for a long time, e.g., the table frame for an airline flight schedule on an indoor sign. LCDs do not have this weakness, but are still susceptible to image persistence.

Each pixel of an LCD typically consists of a layer of molecules aligned between two transparent electrodes, often made of Indium-Tin oxide (ITO) and two polarizing filters (parallel and perpendicular polarizers), the axes of transmission of which are (in most of the cases) perpendicular to each other. Without the liquid crystal between the polarizing filters, light passing through the first filter would be blocked by the second (crossed) polarizer. Before an electric field is applied, the orientation of the liquid-crystal molecules is determined by the alignment at the surfaces of electrodes. In a twisted nematic (TN) device, the surface alignment directions at the two electrodes are perpendicular to each other, and so the molecules arrange themselves in a helical structure, or twist. This induces the rotation of the polarization of the incident light, and the device appears gray. If the applied voltage is large enough, the liquid crystal molecules in the center of the layer are almost completely untwisted and the polarization of the incident light is not rotated as it passes through the liquid crystal layer. This light will then be mainly polarized perpendicular to the second filter, and thus be blocked and the pixel will appear black. By controlling the voltage applied across the liquid crystal layer in each pixel, light can be allowed to pass through in varying amounts thus constituting different levels of gray.

The chemical formula of the liquid crystals used in LCDs may vary. Formulas may be patented.Sharp Corporation. The patent that covered that specific mixture expired.

Most color LCD systems use the same technique, with color filters used to generate red, green, and blue subpixels. The LCD color filters are made with a photolithography process on large glass sheets that are later glued with other glass sheets containing a TFT array, spacers and liquid crystal, creating several color LCDs that are then cut from one another and laminated with polarizer sheets. Red, green, blue and black photoresists (resists) are used. All resists contain a finely ground powdered pigment, with particles being just 40 nanometers across. The black resist is the first to be applied; this will create a black grid (known in the industry as a black matrix) that will separate red, green and blue subpixels from one another, increasing contrast ratios and preventing light from leaking from one subpixel onto other surrounding subpixels.Super-twisted nematic LCD, where the variable twist between tighter-spaced plates causes a varying double refraction birefringence, thus changing the hue.

The optical effect of a TN device in the voltage-on state is far less dependent on variations in the device thickness than that in the voltage-off state. Because of this, TN displays with low information content and no backlighting are usually operated between crossed polarizers such that they appear bright with no voltage (the eye is much more sensitive to variations in the dark state than the bright state). As most of 2010-era LCDs are used in television sets, monitors and smartphones, they have high-resolution matrix arrays of pixels to display arbitrary images using backlighting with a dark background. When no image is displayed, different arrangements are used. For this purpose, TN LCDs are operated between parallel polarizers, whereas IPS LCDs feature crossed polarizers. In many applications IPS LCDs have replaced TN LCDs, particularly in smartphones. Both the liquid crystal material and the alignment layer material contain ionic compounds. If an electric field of one particular polarity is applied for a long period of time, this ionic material is attracted to the surfaces and degrades the device performance. This is avoided either by applying an alternating current or by reversing the polarity of the electric field as the device is addressed (the response of the liquid crystal layer is identical, regardless of the polarity of the applied field).

Displays for a small number of individual digits or fixed symbols (as in digital watches and pocket calculators) can be implemented with independent electrodes for each segment.alphanumeric or variable graphics displays are usually implemented with pixels arranged as a matrix consisting of electrically connected rows on one side of the LC layer and columns on the other side, which makes it possible to address each pixel at the intersections. The general method of matrix addressing consists of sequentially addressing one side of the matrix, for example by selecting the rows one-by-one and applying the picture information on the other side at the columns row-by-row. For details on the various matrix addressing schemes see passive-matrix and active-matrix addressed LCDs.

LCDs are manufactured in cleanrooms borrowing techniques from semiconductor manufacturing and using large sheets of glass whose size has increased over time. Several displays are manufactured at the same time, and then cut from the sheet of glass, also known as the mother glass or LCD glass substrate. The increase in size allows more displays or larger displays to be made, just like with increasing wafer sizes in semiconductor manufacturing. The glass sizes are as follows:

The origins and the complex history of liquid-crystal displays from the perspective of an insider during the early days were described by Joseph A. Castellano in Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry.IEEE History Center.Peter J. Wild, can be found at the Engineering and Technology History Wiki.

In 1888,Friedrich Reinitzer (1858–1927) discovered the liquid crystalline nature of cholesterol extracted from carrots (that is, two melting points and generation of colors) and published his findings at a meeting of the Vienna Chemical Society on May 3, 1888 (F. Reinitzer: Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Cholesterins, Monatshefte für Chemie (Wien) 9, 421–441 (1888)).Otto Lehmann published his work "Flüssige Kristalle" (Liquid Crystals). In 1911, Charles Mauguin first experimented with liquid crystals confined between plates in thin layers.

In 1922, Georges Friedel described the structure and properties of liquid crystals and classified them in three types (nematics, smectics and cholesterics). In 1927, Vsevolod Frederiks devised the electrically switched light valve, called the Fréedericksz transition, the essential effect of all LCD technology. In 1936, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph company patented the first practical application of the technology, "The Liquid Crystal Light Valve". In 1962, the first major English language publication Molecular Structure and Properties of Liquid Crystals was published by Dr. George W. Gray.RCA found that liquid crystals had some interesting electro-optic characteristics and he realized an electro-optical effect by generating stripe-patterns in a thin layer of liquid crystal material by the application of a voltage. This effect is based on an electro-hydrodynamic instability forming what are now called "Williams domains" inside the liquid crystal.

In 1964, George H. Heilmeier, then working at the RCA laboratories on the effect discovered by Williams achieved the switching of colors by field-induced realignment of dichroic dyes in a homeotropically oriented liquid crystal. Practical problems with this new electro-optical effect made Heilmeier continue to work on scattering effects in liquid crystals and finally the achievement of the first operational liquid-crystal display based on what he called the George H. Heilmeier was inducted in the National Inventors Hall of FameIEEE Milestone.

In the late 1960s, pioneering work on liquid crystals was undertaken by the UK"s Royal Radar Establishment at Malvern, England. The team at RRE supported ongoing work by George William Gray and his team at the University of Hull who ultimately discovered the cyanobiphenyl liquid crystals, which had correct stability and temperature properties for application in LCDs.

The idea of a TFT-based liquid-crystal display (LCD) was conceived by Bernard Lechner of RCA Laboratories in 1968.dynamic scattering mode (DSM) LCD that used standard discrete MOSFETs.

On December 4, 1970, the twisted nematic field effect (TN) in liquid crystals was filed for patent by Hoffmann-LaRoche in Switzerland, (Swiss patent No. 532 261) with Wolfgang Helfrich and Martin Schadt (then working for the Central Research Laboratories) listed as inventors.Brown, Boveri & Cie, its joint venture partner at that time, which produced TN displays for wristwatches and other applications during the 1970s for the international markets including the Japanese electronics industry, which soon produced the first digital quartz wristwatches with TN-LCDs and numerous other products. James Fergason, while working with Sardari Arora and Alfred Saupe at Kent State University Liquid Crystal Institute, filed an identical patent in the United States on April 22, 1971.ILIXCO (now LXD Incorporated), produced LCDs based on the TN-effect, which soon superseded the poor-quality DSM types due to improvements of lower operating voltages and lower power consumption. Tetsuro Hama and Izuhiko Nishimura of Seiko received a US patent dated February 1971, for an electronic wristwatch incorporating a TN-LCD.

In 1972, the concept of the active-matrix thin-film transistor (TFT) liquid-crystal display panel was prototyped in the United States by T. Peter Brody"s team at Westinghouse, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.Westinghouse Research Laboratories demonstrated the first thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD).high-resolution and high-quality electronic visual display devices use TFT-based active matrix displays.active-matrix liquid-crystal display (AM LCD) in 1974, and then Brody coined the term "active matrix" in 1975.

Hitachi also improved the viewing angle dependence further by optimizing the shape of the electrodes (Super IPS). NEC and Hitachi become early manufacturers of active-matrix addressed LCDs based on the IPS technology. This is a milestone for implementing large-screen LCDs having acceptable visual performance for flat-panel computer monitors and television screens. In 1996, Samsung developed the optical patterning technique that enables multi-domain LCD. Multi-domain and In Plane Switching subsequently remain the dominant LCD designs through 2006.South Korea and Taiwan,

In 2007 the image quality of LCD televisions surpassed the image quality of cathode-ray-tube-based (CRT) TVs.LCD TVs were projected to account 50% of the 200 million TVs to be shipped globally in 2006, according to Displaybank.Toshiba announced 2560 × 1600 pixels on a 6.1-inch (155 mm) LCD panel, suitable for use in a tablet computer,

In 2016, Panasonic developed IPS LCDs with a contrast ratio of 1,000,000:1, rivaling OLEDs. This technology was later put into mass production as dual layer, dual panel or LMCL (Light Modulating Cell Layer) LCDs. The technology uses 2 liquid crystal layers instead of one, and may be used along with a mini-LED backlight and quantum dot sheets.

Since LCDs produce no light of their own, they require external light to produce a visible image.backlight. Active-matrix LCDs are almost always backlit.Transflective LCDs combine the features of a backlit transmissive display and a reflective display.

CCFL: The LCD panel is lit either by two cold cathode fluorescent lamps placed at opposite edges of the display or an array of parallel CCFLs behind larger displays. A diffuser (made of PMMA acrylic plastic, also known as a wave or light guide/guiding plateinverter to convert whatever DC voltage the device uses (usually 5 or 12 V) to ≈1000 V needed to light a CCFL.

EL-WLED: The LCD panel is lit by a row of white LEDs placed at one or more edges of the screen. A light diffuser (light guide plate, LGP) is then used to spread the light evenly across the whole display, similarly to edge-lit CCFL LCD backlights. The diffuser is made out of either PMMA plastic or special glass, PMMA is used in most cases because it is rugged, while special glass is used when the thickness of the LCD is of primary concern, because it doesn"t expand as much when heated or exposed to moisture, which allows LCDs to be just 5mm thick. Quantum dots may be placed on top of the diffuser as a quantum dot enhancement film (QDEF, in which case they need a layer to be protected from heat and humidity) or on the color filter of the LCD, replacing the resists that are normally used.

WLED array: The LCD panel is lit by a full array of white LEDs placed behind a diffuser behind the panel. LCDs that use this implementation will usually have the ability to dim or completely turn off the LEDs in the dark areas of the image being displayed, effectively increasing the contrast ratio of the display. The precision with which this can be done will depend on the number of dimming zones of the display. The more dimming zones, the more precise the dimming, with less obvious blooming artifacts which are visible as dark grey patches surrounded by the unlit areas of the LCD. As of 2012, this design gets most of its use from upscale, larger-screen LCD televisions.

RGB-LED array: Similar to the WLED array, except the panel is lit by a full array of RGB LEDs. While displays lit with white LEDs usually have a poorer color gamut than CCFL lit displays, panels lit with RGB LEDs have very wide color gamuts. This implementation is most popular on professional graphics editing LCDs. As of 2012, LCDs in this category usually cost more than $1000. As of 2016 the cost of this category has drastically reduced and such LCD televisions obtained same price levels as the former 28" (71 cm) CRT based categories.

Today, most LCD screens are being designed with an LED backlight instead of the traditional CCFL backlight, while that backlight is dynamically controlled with the video information (dynamic backlight control). The combination with the dynamic backlight control, invented by Philips researchers Douglas Stanton, Martinus Stroomer and Adrianus de Vaan, simultaneously increases the dynamic range of the display system (also marketed as HDR, high dynamic range television or FLAD, full-area local area dimming).

A standard television receiver screen, a modern LCD panel, has over six million pixels, and they are all individually powered by a wire network embedded in the screen. The fine wires, or pathways, form a grid with vertical wires across the whole screen on one side of the screen and horizontal wires across the whole screen on the other side of the screen. To this grid each pixel has a positive connection on one side and a negative connection on the other side. So the total amount of wires needed for a 1080p display is 3 x 1920 going vertically and 1080 going horizontally for a total of 6840 wires horizontally and vertically. That"s three for red, green and blue and 1920 columns of pixels for each color for a total of 5760 wires going vertically and 1080 rows of wires going horizontally. For a panel that is 28.8 inches (73 centimeters) wide, that means a wire density of 200 wires per inch along the horizontal edge.

The LCD panel is powered by LCD drivers that are carefully matched up with the edge of the LCD panel at the factory level. The drivers may be installed using several methods, the most common of which are COG (Chip-On-Glass) and TAB (Tape-automated bonding) These same principles apply also for smartphone screens that are much smaller than TV screens.anisotropic conductive film or, for lower densities, elastomeric connectors.

Monochrome and later color passive-matrix LCDs were standard in most early laptops (although a few used plasma displaysGame Boyactive-matrix became standard on all laptops. The commercially unsuccessful Macintosh Portable (released in 1989) was one of the first to use an active-matrix display (though still monochrome). Passive-matrix LCDs are still used in the 2010s for applications less demanding than laptop computers and TVs, such as inexpensive calculators. In particular, these are used on portable devices where less information content needs to be displayed, lowest power consumption (no backlight) and low cost are desired or readability in direct sunlight is needed.

A comparison between a blank passive-matrix display (top) and a blank active-matrix display (bottom). A passive-matrix display can be identified when the blank background is more grey in appearance than the crisper active-matrix display, fog appears on all edges of the screen, and while pictures appear to be fading on the screen.

Displays having a passive-matrix structure are employing Crosstalk between activated and non-activated pixels has to be handled properly by keeping the RMS voltage of non-activated pixels below the threshold voltage as discovered by Peter J. Wild in 1972,

STN LCDs have to be continuously refreshed by alternating pulsed voltages of one polarity during one frame and pulses of opposite polarity during the next frame. Individual pixels are addressed by the corresponding row and column circuits. This type of display is called response times and poor contrast are typical of passive-matrix addressed LCDs with too many pixels and driven according to the "Alt & Pleshko" drive scheme. Welzen and de Vaan also invented a non RMS drive scheme enabling to drive STN displays with video rates and enabling to show smooth moving video images on an STN display.

Bistable LCDs do not require continuous refreshing. Rewriting is only required for picture information changes. In 1984 HA van Sprang and AJSM de Vaan invented an STN type display that could be operated in a bistable mode, enabling extremely high resolution images up to 4000 lines or more using only low voltages.

High-resolution color displays, such as modern LCD computer monitors and televisions, use an active-matrix structure. A matrix of thin-film transistors (TFTs) is added to the electrodes in contact with the LC layer. Each pixel has its own dedicated transistor, allowing each column line to access one pixel. When a row line is selected, all of the column lines are connected to a row of pixels and voltages corresponding to the picture information are driven onto all of the column lines. The row line is then deactivated and the next row line is selected. All of the row lines are selected in sequence during a refresh operation. Active-matrix addressed displays look brighter and sharper than passive-matrix addressed displays of the same size, and generally have quicker response times, producing much better images. Sharp produces bistable reflective LCDs with a 1-bit SRAM cell per pixel that only requires small amounts of power to maintain an image.

Segment LCDs can also have color by using Field Sequential Color (FSC LCD). This kind of displays have a high speed passive segment LCD panel with an RGB backlight. The backlight quickly changes color, making it appear white to the naked eye. The LCD panel is synchronized with the backlight. For example, to make a segment appear red, the segment is only turned ON when the backlight is red, and to make a segment appear magenta, the segment is turned ON when the backlight is blue, and it continues to be ON while the backlight becomes red, and it turns OFF when the backlight becomes green. To make a segment appear black, the segment is always turned ON. An FSC LCD divides a color image into 3 images (one Red, one Green and one Blue) and it displays them in order. Due to persistence of vision, the 3 monochromatic images appear as one color image. An FSC LCD needs an LCD panel with a refresh rate of 180 Hz, and the response time is reduced to just 5 milliseconds when compared with normal STN LCD panels which have a response time of 16 milliseconds.

Samsung introduced UFB (Ultra Fine & Bright) displays back in 2002, utilized the super-birefringent effect. It has the luminance, color gamut, and most of the contrast of a TFT-LCD, but only consumes as much power as an STN display, according to Samsung. It was being used in a variety of Samsung cellular-telephone models produced until late 2006, when Samsung stopped producing UFB displays. UFB displays were also used in certain models of LG mobile phones.

Twisted nematic displays contain liquid crystals that twist and untwist at varying degrees to allow light to pass through. When no voltage is applied to a TN liquid crystal cell, polarized light passes through the 90-degrees twisted LC layer. In proportion to the voltage applied, the liquid crystals untwist changing the polarization and blocking the light"s path. By properly adjusting the level of the voltage almost any gray level or transmission can be achieved.

In-plane switching is an LCD technology that aligns the liquid crystals in a plane parallel to the glass substrates. In this method, the electrical field is applied through opposite electrodes on the same glass substrate, so that the liquid crystals can be reoriented (switched) essentially in the same plane, although fringe fields inhibit a homogeneous reorientation. This requires two transistors for each pixel instead of the single transistor needed for a standard thin-film transistor (TFT) display. The IPS technology is used in everything from televisions, computer monitors, and even wearable devices, especially almost all LCD smartphone panels are IPS/FFS mode. IPS displays belong to the LCD panel family screen types. The other two types are VA and TN. Before LG Enhanced IPS was introduced in 2001 by Hitachi as 17" monitor in Market, the additional transistors resulted in blocking more transmission area, thus requiring a brighter backlight and consuming more power, making this type of display less desirable for notebook computers. Panasonic Himeji G8.5 was using an enhanced version of IPS, also LGD in Korea, then currently the world biggest LCD panel manufacture BOE in China is also IPS/FFS mode TV panel.

In 2015 LG Display announced the implementation of a new technology called M+ which is the addition of white subpixel along with the regular RGB dots in their IPS panel technology.

Most of the new M+ technology was employed on 4K TV sets which led to a controversy after tests showed that the addition of a white sub pixel replacing the traditional RGB structure would reduce the resolution by around 25%. This means that a 4K TV cannot display the full UHD TV standard. The media and internet users later called this "RGBW" TVs because of the white sub pixel. Although LG Display has developed this technology for use in notebook display, outdoor and smartphones, it became more popular in the TV market because the announced 4K UHD resolution but still being incapable of achieving true UHD resolution defined by the CTA as 3840x2160 active pixels with 8-bit color. This negatively impacts the rendering of text, making it a bit fuzzier, which is especially noticeable when a TV is used as a PC monitor.

In 2011, LG claimed the smartphone LG Optimus Black (IPS LCD (LCD NOVA)) has the brightness up to 700 nits, while the competitor has only IPS LCD with 518 nits and double an active-matrix OLED (AMOLED) display with 305 nits. LG also claimed the NOVA display to be 50 percent more efficient than regular LCDs and to consume only 50 percent of the power of AMOLED displays when producing white on screen.

Vertical-alignment displays are a form of LCDs in which the liquid crystals naturally align vertically to the glass substrates. When no voltage is applied, the liquid crystals remain perpendicular to the substrate, creating a black display between crossed polarizers. When voltage is applied, the liquid crystals shift to a tilted position, allowing light to pass through and create a gray-scale display depending on the amount of tilt generated by the electric field. It has a deeper-black background, a higher contrast ratio, a wider viewing angle, and better image quality at extreme temperatures than traditional twisted-nematic displays.

Some manufacturers, notably in South Korea where some of the largest LCD panel manufacturers, such as LG, are located, now have a zero-defective-pixel guarantee, which is an extra screening process which can then determine "A"- and "B"-grade panels.clouding (or less commonly mura), which describes the uneven patches of changes in luminance. It is most visible in dark or black areas of displayed scenes.

The zenithal bistable device (ZBD), developed by Qinetiq (formerly DERA), can retain an image without power. The crystals may exist in one of two stable orientations ("black" and "white") and power is only required to change the image. ZBD Displays is a spin-off company from QinetiQ who manufactured both grayscale and color ZBD devices. Kent Displays has also developed a "no-power" display that uses polymer stabilized cholesteric liquid crystal (ChLCD). In 2009 Kent demonstrated the use of a ChLCD to cover the entire surface of a mobile phone, allowing it to change colors, and keep that color even when power is removed.

Resolution The resolution of an LCD is expressed by the number of columns and rows of pixels (e.g., 1024×768). Each pixel is usually composed 3 sub-pixels, a red, a green, and a blue one. This had been one of the few features of LCD performance that remained uniform among different designs. However, there are newer designs that share sub-pixels among pixels and add Quattron which attempt to efficiently increase the perceived resolution of a display without increasing the actual resolution, to mixed results.

Spatial performance: For a computer monitor or some other display that is being viewed from a very close distance, resolution is often expressed in terms of dot pitch or pixels per inch, which is consistent with the printing industry. Display density varies per application, with televisions generally having a low density for long-distance viewing and portable devices having a high density for close-range detail. The Viewing Angle of an LCD may be important depending on the display and its usage, the limitations of certain display technologies mean the display only displays accurately at certain angles.

Temporal performance: the temporal resolution of an LCD is how well it can display changing images, or the accuracy and the number of times per second the display draws the data it is being given. LCD pixels do not flash on/off between frames, so LCD monitors exhibit no refresh-induced flicker no matter how low the refresh rate.

Color performance: There are multiple terms to describe different aspects of color performance of a display. Color gamut is the range of colors that can be displayed, and color depth, which is the fineness with which the color range is divided. Color gamut is a relatively straight forward feature, but it is rarely discussed in marketing materials except at the professional level. Having a color range that exceeds the content being shown on the screen has no benefits, so displays are only made to perform within or below the range of a certain specification.white point and gamma correction, which describe what color white is and how the other colors are displayed relative to white.

Brightness and contrast ratio: Contrast ratio is the ratio of the brightness of a full-on pixel to a full-off pixel. The LCD itself is only a light valve and does not generate light; the light comes from a backlight that is either fluorescent or a set of LEDs. Brightness is usually stated as the maximum light output of the LCD, which can vary greatly based on the transparency of the LCD and the brightness of the backlight. Brighter backlight allows stronger contrast and higher dynamic range (HDR displays are graded in peak luminance), but there is always a trade-off between brightness and power consumption.

Low power consumption. Depending on the set display brightness and content being displayed, the older CCFT backlit models typically use less than half of the power a CRT monitor of the same size viewing area would use, and the modern LED backlit models typically use 10–25% of the power a CRT monitor would use.

No theoretical resolution limit. When multiple LCD panels are used together to create a single canvas, each additional panel increases the total resolution of the display, which is commonly called stacked resolution.

As an inherently digital device, the LCD can natively display digital data from a DVI or HDMI connection without requiring conversion to analog. Some LCD panels have native fiber optic inputs in addition to DVI and HDMI.

Display motion blur on moving objects caused by slow response times (>8 ms) and eye-tracking on a sample-and-hold display, unless a strobing backlight is used. However, this strobing can cause eye strain, as is noted next:

As of 2012, most implementations of LCD backlighting use pulse-width modulation (PWM) to dim the display,CRT monitor at 85 Hz refresh rate would (this is because the entire screen is strobing on and off rather than a CRT"s phosphor sustained dot which continually scans across the display, leaving some part of the display always lit), causing severe eye-strain for some people.LED-backlit monitors, because the LEDs switch on and off faster than a CCFL lamp.

Only one native resolution. Displaying any other resolution either requires a video scaler, causing blurriness and jagged edges, or running the display at native resolution using 1:1 pixel mapping, causing the image either not to fill the screen (letterboxed display), or to run off the lower or right edges of the screen.

Fixed bit depth (also called color depth). Many cheaper LCDs are only able to display 262144 (218) colors. 8-bit S-IPS panels can display 16 million (224) colors and have significantly better black level, but are expensive and have slower response time.

Input lag, because the LCD"s A/D converter waits for each frame to be completely been output before drawing it to the LCD panel. Many LCD monitors do post-processing before displaying the image in an attempt to compensate for poor color fidelity, which adds an additional lag. Further, a video scaler must be used when displaying non-native resolutions, which adds yet more time lag. Scaling and post processing are usually done in a single chip on modern monitors, but each function that chip performs adds some delay. Some displays have a video gaming mode which disables all or most processing to reduce perceivable input lag.

Subject to burn-in effect, although the cause differs from CRT and the effect may not be permanent, a static image can cause burn-in in a matter of hours in badly designed displays.

Loss of brightness and much slower response times in low temperature environments. In sub-zero environments, LCD screens may cease to function without the use of supplemental heating.

Several different families of liquid crystals are used in liquid crystal displays. The molecules used have to be anisotropic, and to exhibit mutual attraction. Polarizable rod-shaped molecules (biphenyls, terphenyls, etc.) are common. A common form is a pair of aromatic benzene rings, with a nonpolar moiety (pentyl, heptyl, octyl, or alkyl oxy group) on one end and polar (nitrile, halogen) on the other. Sometimes the benzene rings are separated with an acetylene group, ethylene, CH=N, CH=NO, N=N, N=NO, or ester group. In practice, eutectic mixtures of several chemicals are used, to achieve wider temperature operating range (−10..+60 °C for low-end and −20..+100 °C for high-performance displays). For example, the E7 mixture is composed of three biphenyls and one terphenyl: 39 wt.% of 4"-pentyl[1,1"-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 24..35 °C), 36 wt.% of 4"-heptyl[1,1"-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 30..43 °C), 16 wt.% of 4"-octoxy[1,1"-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 54..80 °C), and 9 wt.% of 4-pentyl[1,1":4",1-terphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 131..240 °C).

The production of LCD screens uses nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) as an etching fluid during the production of the thin-film components. NF3 is a potent greenhouse gas, and its relatively long half-life may make it a potentially harmful contributor to global warming. A report in Geophysical Research Letters suggested that its effects were theoretically much greater than better-known sources of greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide. As NF3 was not in widespread use at the time, it was not made part of the Kyoto Protocols and has been deemed "the missing greenhouse gas".

Castellano, Joseph A (2005). Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-238-956-5.

Rong-Jer Lee; Jr-Cheng Fan; Tzong-Shing Cheng; Jung-Lung Wu (March 10, 1999). "Pigment-dispersed color resist with high resolution for advanced color filter application". Proceedings of 5th Asian Symposium on Information Display. ASID "99 (IEEE Cat. No.99EX291). pp. 359–363. doi:10.1109/ASID.1999.762781. ISBN 957-97347-9-8. S2CID 137460486 – via IEEE Xplore.

Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry, Joseph A. Castellano, 2005 World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., ISBN 981-238-956-3.

Tim Sluckin: Ueber die Natur der kristallinischen Flüssigkeiten und flüssigen Kristalle (About the Nature of Crystallised Liquids and Liquid Crystals), Bunsen-Magazin, 7.Jahrgang, 5/2005

Gray, George W.; Kelly, Stephen M. (1999). "Liquid crystals for twisted nematic display devices". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 9 (9): 2037–2050. doi:10.1039/a902682g.

Heilmeier, George; Castellano, Joseph; Zanoni, Louis (1969). "Guest-Host Interactions in Nematic Liquid Crystals". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 8: 293–304. doi:10.1080/15421406908084910.

Heilmeier, G. H.; Zanoni, L. A.; Barton, L. A. (1968). "Dynamic scattering: A new electrooptic effect in certain classes of nematic liquid crystals". Proc. IEEE. 56 (7): 1162–1171. doi:10.1109/proc.1968.6513.

Kawamoto, H. (2012). "The Inventors of TFT Active-Matrix LCD Receive the 2011 IEEE Nishizawa Medal". Journal of Display Technology. 8 (1): 3–4. Bibcode:2012JDisT...8....3K. doi:10.1109/JDT.2011.2177740. ISSN 1551-319X.

Brody, T. Peter; Asars, J. A.; Dixon, G. D. (November 1973). "A 6 × 6 inch 20 lines-per-inch liquid-crystal display panel". 20 (11): 995–1001. Bibcode:1973ITED...20..995B. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1973.17780. ISSN 0018-9383.

Heilmeier, G. H., Castellano, J. A. and Zanoni, L. A.: Guest-host interaction in nematic liquid crystals. Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst. vol. 8, p. 295, 1969.

Hirohisa Kawamoto (2013), The history of liquid-crystal display and its industry, HISTory of ELectro-technology CONference (HISTELCON), 2012 Third IEEE, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, DOI 10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487587

Competing display technologies for the best image performance; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; Journal of the society of information displays, Volume 15, Issue 9 September 2007 Pages 657–666; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1889/1.2785199/abstract?

Pixel-by-pixel local dimming for high dynamic range liquid crystal displays; H. Chen; R. Zhu; M.C. Li; S.L. Lee and S.T. Wu; Vol. 25, No. 3; 6 Feb 2017; Optics Express 1973; https://www.osapublishing.org/oe/viewmedia.cfm?uri=oe-25-3-1973&seq=0

Broadband reflective polarizers based on form birefringence for ultra-thin liquid crystal displays; S.U. Pan; L. Tan and H.S. Kwok; Vol. 25, No. 15; 24 Jul 2017; Optics Express 17499; https://www.osapublishing.org/oe/viewmedia.cfm?uri=oe-25-15-17499&seq=0

P. J. Wild, Matrix-addressed liquid crystal projection display, Digest of Technical Papers, International Symposium, Society for Information Display, June 1972, pp. 62–63.

NXP Semiconductors (October 21, 2011). "UM10764 Vertical Alignment (VA) displays and NXP LCD drivers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

"Display (LCD) replacement for defective pixels – ThinkPad". Lenovo. June 25, 2007. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

Timothy J. Sluckin History of Liquid Crystals, a presentation and extracts from the book Crystals that Flow: Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals.

When historians look back on our modern era, they will list a number of defining features of the age. Alongside the Internet will be the ubiquitous nature of the ‘screen’. No matter where you go, home, work, traveling, look around and you will likely see display screens everywhere. From the smartwatch on your wrist to the smartphone you are using to read this to your TV screen, the technology behind that screen, Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) has been a vital part of making our modern world shine.

‘Liquid crystals’ were first discovered in 1888 by botanist Freidrich Reinitzer. However, LCD as a technological innovation for light displays entered the world as a unique and powerful solution to the power-hungry LED back in the 1960s.

In the early 1960s, George H. Heilmeier was a Ph.D. student in electrical engineering, working for RCA Laboratories (later acquired by SRI International). He was interested in organic semiconductors, carbon-based molecules that exist in the form of crystals or thin films. From this interest area, he moved into the field of electro-optic effects in liquid crystals; 1964 was the year that Heilmeier discovered several new types of effect. From this work, Heilmeier became the first person to demonstrate a working LCD display. Heilmeier then went on to be DARPA Director and created the Heilmeier Catechism. The rest is history…But what makes a Liquid Crystal Display work?

Heilmeier also determined two mechanisms of the modes of operation of LCD. Heilmeier placed different dyes into the crystal cell and then passed a current through. He noted that the dyes would change color and that this color could be controlled by varying the current: This was termed the “guest-host (GH) effect”.

The experiments continued. It was found that when light was shone onto a liquid crystal cell and then an electric current applied, the cell would turn a milky white color. If the current was increased, the opacity would also increase. This was theorized to be caused by the current changing the orientation of the liquid crystal molecules and causing light to be scattered at various angles. Heilmeier then noted the light scattered in a forward direction and this phenomenon was used to improve the brightness of displays. To do so, Heilmeier placed reflective material onto the side of a cell in the direction of the scattered light; this caused the photons to bounce back into the cell and brighten the display.

LCD was a vitally needed replacement technology for the heavy power consuming Light Emitting Diodes (LED) and Vacuum Fluorescent Displays (VFD) used in consumer products like watches and calculators; optimizing battery life for battery-powered devices was an important step in the development of consumer electronic products.

LCD has spawned new and even more innovative display types including thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT-LCD), the market value of which is expected to be $195 billion by 2023. The development of LCD into a commercially useful technology drove the development of low-power and portable screens that our highly connected world of smartphones, laptops, touch-screen computers, and many IoT devices depend on.

George H. Heilmeier died in 2014, but the era of the screen is down to his clever manipulation of light using liquid crystals. In 2009 George Heilmeier was rewarded with inclusion in the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Heilmeier GH, Zanoni LA, Barton LA. 1968. Dynamic scattering: A new electrooptic effect in certain classes of nematic liquid crystals. Proceedings of the IEEE 56(7):1162–1171.

George H. Heilmeier, “Liquid Crystal Displays: An Experiment in Interdisciplinary Research that 61 Worked,” IEEE Trans. on Electron Devices ED-23, no. 7 (Jul. 1976): 780–785.

Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) screens are a staple in the digital display marketplace and are used in display applications across every industry. With every display application presenting a unique set of requirements, the selection of specialized LCDs has grown to meet these demands.

LCD screens can be grouped into three categories: TN (twisted nematic), IPS (in-plane switching), and VA (Vertical Alignment). Each of these screen types has its own unique qualities, almost all of them having to do with how images appear across the various screen types.

This technology consists of nematic liquid crystal sandwiched between two plates of glass. When power is applied to the electrodes, the liquid crystals twist 90°. TN (Twisted Nematic) LCDs are the most common LCD screen type. They offer full-color images, and moderate viewing angles.

TN LCDs maintain a dedicated user base despite other screen types growing in popularity due to some unique key features that TN display offer. For one,

VA, also known as Multi-Domain Vertical Alignment (MVA) dislays offer features found in both TN and IPS screens. The Pixels in VA displays align vertically to the glass substrate when voltage is applied, allowing light to pass through.

Displays with VA screens deliver wide viewing angles, high contrast, and good color reproduction. They maintain high response rates similar to TN TFTs but may not reach the same sunlight readable brightness levels as comparable TN or IPS LCDs. VA displays are generally best for applications that need to be viewed from multiple angles, like digital signage in a commercial setting.

IPS (In-Plane Switching) technology improves image quality by acting on the liquid crystal inside the display screen. When voltage is applied, the crystals rotate parallel (or “in-plane”) rather than upright to allow light to pass through. This behavior results in several significant improvements to the image quality of these screens.

IPS is superior in contrast, brightness, viewing angles, and color representation compared to TN screens. Images on screen retain their quality without becoming washed out or distorted, no matter what angle they’re viewed from. Because of this, viewers have the flexibility to view content on the screen from almost anywhere rather than having to look at the display from a front-center position.

IPS displays offer a slightly lower refresh rate than TN displays. Remember that the time for pixels to go from inactive to active is measured in milliseconds. So for most users, the difference in refresh rates will go unnoticed.

Based on current trends, IPS and TN screen types will be expected to remain the dominant formats for some time. As human interface display technology advances and new product designs are developed, customers will likely choose IPS LCDs to replace the similarly priced TN LCDs for their new projects.

Spatial uniformity of displayed luminance can vary widely between different makes and models of LCD, the major determinant of uniformity being the backlight scheme [34] (some older LCDs allowed VGA input and relied on built-in analog-to-digital conversion, also a potential source of noise). Two commonplace schemes are, first, direct backlighting, wherein a spatial array of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and a diffuser screen sit behind the liquid crystal panel, and, second, edge illumination, wherein light emitted by a linear array of diodes at one of the display’s edges is spatially distributed via lightguide. We quantified the spatial uniformity of the CG247X by presenting low-, medium-, and high-luminance static test patches at nine display positions (Fig 2, inset) and using the LS-110 spot meter to measure the luminance of each patch. At each luminance tested, we calculated the grand average over all display positions, and divisively normalized measurements by that average. As illustrated in Fig 2, at medium- and high-luminance, the CG247X showed greater spatial uniformity than our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b): for the CG247X, spatial variation was 5.1% at medium and 3.5% at high luminance, whereas for the U2415b, variation was 8.1% at medium and 8.5% at high luminance. The uniformity of the two displays was comparable at low luminance (CG247X, 27% versus U2415b, 17%). Prior to normalization, there were, as expected, marked differences between low-, medium-, and high-luminance measurements. For example, at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) on the CG247X, low-luminance measurements ranged from 0.07 to 0.10 cd/m2, medium-luminance measurements ranged from 57.70 to 57.93 cd/m2, and high-luminance measurements ranged from 113.9 to 114.2 cd/m2 (Table 1). We also quantified spatial surround effects; using a tripod at 1 m, we measured displayed luminance at position 5 comparing large (1920-by-1200 pixels) and small (384-by-384 pixels) 100%-luminance patches. For CG247X, the mean of 10 large-patch measurements was 0.56 cd/m2 greater than that of 10 small-patch measurements (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01), i.e., an increase of 0.50%. For the U2415b, the increase was 0.71 cd/m2, i.e., 0.67% (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01).

In-plane switching (IPS) LCDs, like our CG247X and U2415b, enable larger viewing angles than older LCD technology (e.g., twisted-nematic displays) [23]. To do so, IPS displays interdigitate electrodes (see 23]. For the displays we tested, vendor-issued specifications state a viewing angle of 178 deg, however, in the absence of further details, that derived measure is difficult to assimilate. We measured displayed luminance as a function of viewing angle over a range of azimuth and elevation (±60 deg). We fit a circular von Mises function (Fig 3, the CG247X and U2415b performed comparably in this regard. For the CG247X, the FW90M was 28.6 deg (fitted parameters: α = 1.45, κ = 3.37) and 32.6 deg (α = 1.65, κ = 2.62) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. For the U2415b, the FW90M was 31.2 deg (α = 1.60, κ = 2.85) and 31.0 deg (α = 1.55, κ = 2.90) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. At high-luminance we made a reduced set of measurements, assuming rotational symmetry, varying azimuth or elevation from 0 to 60 deg. These additional measurements yielded similar FW90M estimates. This descriptive model can be used to select a viewing distance with tolerable attenuation due to viewing angle. For example, if the CG247X is viewed from 1 m, a stimulus presented at the top of the display’s vertical meridian (i.e., elevation = 9.2 deg) would, due to viewing angle, undergo luminance attenuation by a factor of 0.97.

We presented a large, static test patch, measuring luminance with the LS-110 spot meter near the display’s center. We used a turntable to rotate the display (

A common misconception among vision researchers and clinicians is that LCDs do not flicker (i.e., that LCDs are temporally uniform). In fact, there are two major sources of flicker that can affect a LCD: first, backlight flicker which usually occurs at temporal frequencies (e.g., 1000 Hz) well beyond the critical flicker fusion frequency (e.g., Elze & Tanner [24], and Ghodrati, Morris, & Price [35]), and, second, the so-called frame response which occurs at the refresh rate of the display (here, 60 Hz) [23, 36]. Frame responses are largely attributable to an LCD’s inversion scheme: a feature of modern displays wherein the polarity of the video signal voltage applied to the liquid crystal material is inverted from one video frame to the next. This inversion minimises long-term degradation, or aging, of the display by minimizing the DC voltage across the liquid crystal elements. Frame inversion schemes typically have fine spatial structure, on the scale of individual pixels, making them mostly imperceptible (e.g., dot inversion schemes [36]). We quantified the temporal uniformity of the CG247X by presenting (nominally) static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) and using the linearized photodiode device to measure displayed luminance over time. At each of 11 luminances (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made 10 one-second recordings, averaging the Fourier amplitude spectra of those 10 recordings. Fig 4 shows the average spectrum at each luminance. The spectra of the CG247X revealed a frame response comprising a 60 Hz component as well as harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. The response at 60 Hz varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking at a luminance of 50%. However, the CG247X appeared free of backlight modulations. This absence of backlight modulations freed us of the consequences of said modulations (often desynchronized with the frame refresh signal) on increment/decrement transitions between luminances (see Fig 5 in [24]). The spectra of our consumer-grade LCD also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, likely associated with the back light. This latter temporal nonuniformity increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch.

We presented nominally static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset), measuring luminance with a linearized photodiode device. At each luminance (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made ten 1-second recordings, deriving the Fourier amplitude spectrum for each. Each spectrum illustrated is the average of 10 spectra. For each display, we normalized spectra such that 1000 corresponds to the DC component at 50% luminance; therefore, a value of 5.0 corresponds to approximately 0.15 cd/m2. The spectra of the CG247X (upper) revealed a frame response, comprising a 60 Hz component and harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. This frame response varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking between 40 and 50% luminance. The spectra of the U2415b (lower) also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, the amplitude of which increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch (amplitudes above 5.0 are not shown, arrowheads). For the U2415b, mains noise (50 Hz) was apparent at high-luminance. lum., luminance.

For each display, we verified that the frame response was optical and not related to any radiated electromagnetic noise: We used the oscilloscope to visualize the Fourier amplitude spectrum online. We then interposed opaque cardboard between the photodiode and display which caused the disappearance of the frame response. For the U2415b, we similarly verified that the 1.2 kHz response was optical.

In general, LCD response times—the duration of the rise or fall of a step from one luminance level to another—vary as a function of both step source and destination luminance. This nonlinear behaviour is owing largely to mechanisms of response time compensation (RTC) (e.g., the work of McCartney [25]), a feature of many modern LCDs designed to enhance video. RTC mechanisms speed luminance transitions by transiently altering the voltage applied to the liquid crystal associated with individual pixels (e.g., Fig 1 in [27]; Fig 5 in [24]). We measured the CG247X’s response times by presenting luminance steps—both increments and decrements—to the linearized photodiode device. Step source and destination took values 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100%. As illustrated in Fig 5, response times varied as a function of both luminance step source and destination. For example, stepping from 0% luminance to 25% luminance took 24.5 ms, stepping from 75% to 100% took 12.9 ms, and stepping from 25% to 0% took 8.1 ms. All of these steps are the same height, but response times differ markedly. Overall, the response times of our consumer-grade LCD were less than the CG247X response times. However, as we will illustrate below, faster is not better; although RTC mechanisms reduced the response times of our consumer-grade LCD, they contaminated displayed luminance with overshoot and undershoot artifacts which are problematic for many applications in clinical and experimental vision research, including the presentation of mean-modulated flicker. RTC mechanisms lower “black-white-black” and “grey-to-grey” response times, which are used to promote displays to the gaming community and other consumer markets.

At the outset of this study, we made preliminary measurements similar to those illustrated in Fig 5. We noticed that rise and fall times straddling 50% luminance were approximately equal (e.g., rise time from 25% to 75% = 16.3 ms; fall time from 75% to 25% = 17.1 ms) which led us to wonder whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts. To better determine the CG247X’s potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker, and its susceptibility, or otherwise, to overshoot and undershoot artifacts typical of LCDs implementing RTC mechanisms, we presented mean-modulated flicker on both the CG247X and our consumer-grade display, using the linearized photodiode device to measure luminance over time. We used a flicker period of 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast ranging from 20 to 100%. As illustrated in Fig 6, the consumer-grade display’s luminance traces revealed overshoot and undershoot artifacts symptomatic of RTC. The CG247X’s luminance traces, however, appeared free of RTC artifacts. We used these traces to estimate response times specific to mean-modulated flicker, illustrated in Fig 7. Overall, CG247X rise and fall times were greater than those of our consumer-grade LCD. However, with the exception of 100% contrast, CG247X rise and fall times were approximately equal, indicating its potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker.

Flicker period = 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast = 20 to 100% in increments of 20 as marked. At 40% contrast, the arrowheads show examples of luminance step source and destination as used in the computation of response times (Fig 7). For each display, we normalized traces to the luminance step destination at 100% contrast. For the U2415b, over- and undershoot are readily apparent at low and moderate contrast. The CG247X, however, shows exponential rise and fall, regardless of contrast.

To further determine whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts, we presented flicker at frequencies ranging from 0.94 to 30 Hz and contrasts ranging from 20 to 100%. We used recorded traces (similar to those in Fig 6) to derive cycle-averaged luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for all flicker frequencies, and for contrasts up to 80%. At 100% contrast, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicating that, at full contrast, the monitor is not suitable for presenting mean-modulated flicker. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b) varied as a function of flicker frequency at all contrasts tested; this variation is problematic for presenting achromatic, mean-modulated flicker. We also used CG247X traces to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of loss of contrast. The consumer-grade LCD was affected by both changes in cycle-averaged luminance and loss of contrast.

We presented mean-modulated flicker at a range of flicker frequencies (0.94 to 30 Hz) and contrasts (20 to 100%). We used waveforms (e.g., Fig 6) recorded from the CG247X (A) to derive cycle-averaged luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using the cycle-averaged luminance of a “reference” waveform, that is, the response to contrast = 20% and flicker frequency = 0.94 Hz. This relatively low-contrast, low-frequency waveform was chosen as reference because it should be easily realized by both displays. For clarity, cycle-averaged responses for contrast = 40, 60, 80, and 100% are offset by -0.1, -0.2, -0.3, and -0.4 log units, respectively (arrowheads). As shown, cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for contrast = 20 to 80% at all flicker frequencies tested (0.94 to 30 Hz). At contrast = 100%, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from the consumer-grade U2415b (B) increased with flicker frequency at all contrasts tested. Graphical conventions are as in A. We used waveforms recorded from the CG247X (C) to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance of the reference waveform (20%, 0.94 Hz). As shown, at all contrasts tested (20 to 100%), cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of a loss of effective contrast. Cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance recorded from the U2415b (D) revealed both increases and decreases to effective contrast with flicker frequency. Each symbol is the average of 10 measurements. (None of the data in panels C and D is offset.) We modeled cycle-average luminance and r.m.s. luminance on the CG247X as a causal exponential decay (Methods). This model comprised one free parameter, τ. For the illustrated fit (blue), τ = 6.6 ms. The red symbols in panel C (slightly offset rightward for clarity) show the result of a validation experiment (see

Taken together, Fig 8, and the traces used to derive the measures plotted there, indicated a simple relationship between nominal and displayed luminance on the CG247X, namely, that the latter was, simply, a low-pass-filtered version of the former. To test this hypothesis, we modeled the function transferring nominal luminance to displayed luminance as a causal, exponential decay (Methods). We optimized the single free parameter in this model, the time constant of the exponential decay (τ), by minimizing the sum of the squared error between the model-derived cycle-averaged mean luminance and cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, and those derived from the photodiode traces. For the CG247X, the fit is illustrated in Fig 8 (blue). There, the fitted parameter, τ, was 6.6 ms. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged luminance, we computed the root-mean-square error (RMSE) separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, the RMSE was negligibly small for contrasts from 20 to 80% (ranging from 6.0e-4 to 6.3e-3 normalized units). At 100% contrast, RMSE was highest at 0.093. This simple model was a poor fit to the U2415b, not illustrated in Fig 8. For the U2415b, RMSEs were high, ranging from 0.04 at 20% contrast to 0.15 at 60% contrast. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, we calculated the square of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, R2, separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, R2 was high, ranging from 0.9965 to 0.9999. As expected, the same calculation for the U2415b was consistent with a poor fit; at its worst, R2 = 0.03.

To quantify the nonlinea

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey