display screens at work regulations made in china

Taiwanese lawmakers approved the “Child and Youth Welfare and Protection Act,” which expanded existing legislation to allow the government to fine parents of children under the age of 18 who are using electronic devices for extended periods of times. The law follows similar measures in China and South Korea that aims to limit screen time to a healthy level.

Citing health concerns, the Taiwanese government can fine parents up to $1595 ($50,000 Taiwanese Dollars) if their child’s use of electronic devices “exceeds a reasonable time,” according toTaiwan’s ETTV (and Google Translate). Under the new law, excess screen time is now considered to be the equivalent of vices like smoking, drinking, using drugs, and chewing betel nuts.

The new amendment doesn’t spell out exactly what time limits should be set on electronic devices (which are called 3C products in Taiwan), but says parents can be held liable if their children stare at screens for so long that its causes them to become ill, either physically or mentally, as Kotaku reports. While that should be O.K. for children angling for 15 more minutes of Minecraft, it’s unclear what is considered “reasonable” under the law— or how the Taiwanese government plans to regulate or monitor screen time.

According to Kotaku, so far the response to the legislation has been negative—which it undoubtedly would be in the U.S. as well—with Taiwanese citizens citing privacy concerns.

There are some parents however, who might welcome a little help prying their children’s eyes off screens. Studies have shown that excessive media use can lead to attention issues, behavioral problems, learning difficulties, sleep disorders, and obesity. Too much time online may even inhibit a child’s ability to recognize emotions, according toa study by the University of California, Los Angeles. Despite these risks, as technology increasingly becomes a part of modern life, children are spending more and more time in front of screens. A recent study found that in the U.S. 8-year-olds spend an average of eight hours a day with some form of media, with teenagers often clocking in at 11 hour a day of media consumption. A 2013 study by Nickelodeon found that kids watch an average of 35 hours a week of television.

So how much is too much screen time? According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children under the age of two should have no screen time at all. Entertainment screen time should be limited to two hours a day for children ages 3-18, and that should be “high-quality content.” Common Sense Media, a San Francisco-based non-profit, has suggestions for setting up a “media diet”that works for your family.

TIME family subscribers can read our in-depth report on Raising the Screen Generation here. And don’t forget to sign up for Time’s free parenting newsletter.

The answer can vary a good bit among U.S. jurisdictions, especially as to whether screens can work for lawyers moving from one law firm to another. Getting an answer often requires studying the applicable local ethics rule and the applicable jurisdiction’s case law. But also, it’s necessary to determine who’s covered by screening rules, such as paralegals and summer associates. (For help with this research, see the resources mentioned below.)

Pretty much all lawyers know what screens are, at least generally. But many lawyers don’t realize the many ways in which they can (or must) be used. Screens are used:

where law firms take on representations adverse to prospective clients of the firm—people who consulted a firm lawyer about hiring the firm, but who did not become clients (ABA Model Rule 1.18(d));

where former judges or third-party neutrals in a firm are disqualified from participation in a matter being handled by the firm (ABA Model Rule 1.12(c));

where, as a condition of waiving a conflict of interest, a client or former client wants to isolate lawyers who work or worked on their matter from those working on a matter creating the conflict (ABA Model Rules 1.7(b) and 1.9(a)).

In 2018, California finally joined the rest of the country in adopting ethics rules patterned upon the ABA Model Rules. (Ethics nerds rejoiced.) As part of this reform, California’s rules permitted screening to avoid disqualification for laterally moving lawyers for the first time.

Some may also recall that, a few years back, the California State Bar split into a state bar concerned only with lawyer regulation and the California Lawyers Association (CLA), their new voluntary bar. One benefit is that both now issue ethics opinions.

The very first topic addressed by the California Lawyers Association? “Elements of Effective Ethical Screens” in their Formal Op. 2021-1. It’s a nice 10-page primer on what makes an ethical screen compliant with their new rule.

California’s rules governing effective screens (California Rule 1.0.1(k) and its Comment [5]) vary slightly from ABA language (ABA Model Rule 1.0(k) and Comments [8]–[10]), but only because California includes language requiring that a screen protect against firm personnel other than the screened lawyer “communicating with the [screened] lawyer with respect to the matter.” Under any jurisdiction’s rules, good screens do this.

So, while there are some minor variations among the jurisdictions about the particular required bells and whistles required for an effective screen, the CLA’s first-ever ethics opinion is a nice introduction to the construction requirements.

Let’s look at the building code for required screens. (Of course, where screens are consensual, as an element of a conflict waiver, the requirements are a fit subject of negotiation.) As the California opinion notes, the precise facts of each situation matter enormously here, so pay close heed to them.

As soon as the necessity of a screen arises, the screen needs to be built. When the need arises from a lawyer moving to a new firm, a screen should be in place promptly upon the lawyer joining their new firm. When the need arises from the firm accepting a new matter adverse to a prospective client whose matter the firm never accepted, a screen should be in place promptly upon the firm accepting the new matter adverse to the prospective client.

Life happens, and sometimes the need for screening only becomes apparent after the perfect moment to erect the screen. When that happens, quick action is still essential, plus confirmation that no communication that would have been barred actually happened, plus careful documentation of that fact, confirmed by the relevant actors. With luck, you can prove it—no harm, no foul.

But more than a few decided cases have found screens ineffective, and disqualified a law firm, where the court found the firm did not erect a screen as soon as reasonably possible following discovery of a conflict.

Second, communications across the screen must be prohibited to firm or office personnel. This ban needs to be clearly communicated, acknowledged and documented.

The ban also needs to be real, and violations need to lead to real consequences. The best screens communicate this upfront, warning that violators will be punished. Of course, any actual violations need to be addressed appropriately.

In today’s digital age, most firms can (and should) not merely communicate and acknowledge the prohibition orally and in writing but should also explore electronic means to actually make some such banned communications impossible. Check with your tech guru to see if you can either lock the new lawyer out of the parts of the firm’s case management or document management systems that concern the files from which they are screened or restrict access to those parts of the system to only an identified list of firm personnel. And check to make sure any system option to track and log who accesses the restricted files is fully enabled. As the California opinion says, a simple directive may be sufficient, but the more steps a firm has taken to prevent any disclosure, the more likely the ethical screen is to be found adequate.

Constructing an effective screen might well also affect personnel assignments and office logistics. If lawyers on opposite sides of the screen share a paralegal or associate, perhaps that should be adjusted. And perhaps firm personnel on opposite sides of the screen should not have offices next door to each other or share printers. Details matter.

Third, a screened person cannot share fees arising from the screened matter. The point is to remove any financial incentive for the screened lawyer to assist.

Screened personnel cannot receive compensation directly related to the matter from which they are screened. Bonuses based on the overall profitability of the firm are fine.

Notice requirements vary among jurisdictions, but the usual purpose is to provide affected clients sufficient information to evaluate the effectiveness of the screen. Depending on the purpose of the screen and applicable rules and law, the form and content may vary. Check the applicable rules and comply.

Further, where notice is required, those receiving notice do sometimes have questions. Depending on the situation, the firm sending notice may well have an obligation to respond to reasonable questions from those receiving notice.

Many lawyers and lawyer regulators have no idea how much of the realm of conflicts of interest is regulated by the negotiated consent of lawyers and clients. A large part of this regulation is accomplished by waivers of conflicts that often include elements of screening.

In most circumstances, the legal requirements for an adequate screen under the ethics rules provide the best guidance on what is required for an effective consensual screen. However, lawyers and clients have flexibility to require more, or less, protection than the ethics rules in their consensual screen.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

QUITO, Ecuador — The squat gray building in Ecuador’s capital commands a sweeping view of the city’s sparkling sprawl, from the high-rises at the base of the Andean valley to the pastel neighborhoods that spill up its mountainsides.

The police who work inside are looking elsewhere. They spend their days poring over computer screens, watching footage that comes in from 4,300 cameras across the country.

The high-powered cameras send what they see to 16 monitoring centers in Ecuador that employ more than 3,000 people. Armed with joysticks, the police control the cameras and scan the streets for drug deals, muggings and murders. If they spy something, they zoom in.

Ecuador’s system, which was installed beginning in 2011, is a basic version of a program of computerized controls that Beijing has spent billions to build out over a decade of technological progress. According to Ecuador’s government, these cameras feed footage to the police for manual review.

But a New York Times investigation found that the footage also goes to the country’s feared domestic intelligence agency, which under the previous president, Rafael Correa, had a lengthy track record of following, intimidating and attacking political opponents. Even as a new administration under President Lenín Moreno investigates the agency’s abuses, the group still gets the videos.

Under President Xi Jinping, the Chinese government has vastly expanded domestic surveillance, fueling a new generation of companies that make sophisticated technology at ever lower prices. A global infrastructure initiative is spreading that technology even further.

Ecuador shows how technology built for China’s political system is now being applied — and sometimes abused — by other governments. Today, 18 countries — including Zimbabwe, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Kenya, the United Arab Emirates and Germany — are using Chinese-made intelligent monitoring systems, and 36 have received training in topics like “public opinion guidance,” which is typically a euphemism for censorship, according to an October report from Freedom House, a pro-democracy research group.

With China’s surveillance know-how and equipment now flowing to the world, critics warn that it could help underpin a future of tech-driven authoritarianism, potentially leading to a loss of privacy on an industrial scale. Often described as public security systems, the technologies have darker potential uses as tools of political repression.

“They’re selling this as the future of governance; the future will be all about controlling the masses through technology,” Adrian Shahbaz, research director at Freedom House, said of China’s new tech exports.

Companies worldwide provide the components and code of dystopian digital surveillance and democratic nations like Britain and the United States also have ways of watching their citizens. But China’s growing market dominance has changed things. Loans from Beijing have made surveillance technology available to governments that could not previously afford it, while China’s authoritarian system has diminished the transparency and accountability of its use.

For locals seeking to push back, there is little recourse. Chinese companies operate with less scrutiny and regard for corporate social responsibility than their Western counterparts. Activists in Ecuador say that while they have succeeded in working with civil society groups in Europe and America to oppose sales of surveillance technologies, similar campaigns in China have not been possible.

In a statement, Huawei said: “Huawei provides technology to support smart city and safe city programs across the world. In each case, Huawei does not get involved in setting public policy in terms of how that technology is used.”

In Ecuador, the cameras that are part of ECU-911 hang from poles and rooftops, from the Galápagos Islands to the Amazonian jungle. The system lets the authorities track phones and may soon get facial-recognition capabilities. Recordings allow the police to review and reconstruct past incidents.

While ECU-911 was sold to the public as a way to get a grip on dizzying murder rates and drug-related petty crime, it also served Mr. Correa’s authoritarian streak, supporting his feared National Intelligence Secretariat, or Senain, according to a former head of the group. In a rare interview last year at Senain’s headquarters in a bunker outside Quito, its leader at the time, Jorge Costa, confirmed that the domestic intelligence group had access to a mirror of the Chinese-built surveillance system.

The irony is that ECU-911 has not been effective at stopping crime, many Ecuadoreans said, though the system’s installation paralleled a period of falling crime rates. Ecuadoreans cite muggings and attacks that happened in front of the cameras without police response. Still, the police have built public support, partly by releasing clips on Twitter and television of thieves and muggers caught on camera.

Left to choose between privacy and safety, many Ecuadoreans opt for the unblinking gaze of the electronic eyes. With the mass surveillance genie out of the bottle, community leaders have called for cameras to help secure their neighborhoods, even when their own experiences are that the devices do not work well. Concerns about the long-term political implications trail behind the pressing realities of violence and drugs.

Mr. Moreno, who came to power in 2017 and has walked back some of Mr. Correa’s autocratic policies, has vowed to investigate Senain’s abuses and is remaking the intelligence collection agency under a new name. His government helped open up ECU-911 and Senain to The Times.

“The government viewed espionage as a toolbox, and they could use any tool they wanted,” Ms. Roldós said. “They could spy on your emails, your phone calls, they would set microphones on your vehicle. At the same time, you had people following you. It was a whole system.”

Before those Games, a delegation from Ecuador visited Beijing and toured the Chinese capital’s surveillance system. At the time, Beijing was pulling footage from 300,000 cameras to keep tabs on 17 million people. The Ecuadoreans left impressed.

“For the Olympics, China developed emergency response centers which had state-of-the-art technology for its time,” Francisco Robayo, then the general director of ECU-911, said in an interview last year. “Our authorities saw these as ideal to bring to Ecuador.”

Mr. Correa’s ministers turned to China. In two months, details to install a Chinese-made technology system were ironed out with the help of military attachés from the Chinese Embassy in Quito, according to a person familiar with the process and to publicly available documents from Ecuador’s comptroller. Ecuadorean officials traveled again to Beijing to scope out the system, which featured technology made by the parent company of the state-backed C.E.I.E.C.

By February 2011, with guarantees of state funding from the attachés, Ecuador signed a deal with no public bidding process. The country got a Chinese-designed surveillance system financed by Chinese loans. In exchange, Ecuador provided one of its main exports, oil. The money for the cameras and computing flowed straight to C.E.I.E.C. and Huawei.

It became a pattern. In exchange for credit facilities that totaled more than $19 billion, Ecuador signed away large portions of its oil reserves. A surge of Chinese-built infrastructure projects, including hydroelectric dams and refineries, followed.

With an initial sticker price of more than $200 million, construction started near Guayaquil, a booming coastal city where crime rates are high, Mr. Robayo said. Over the next four years, the system expanded across Ecuador.

Cameras were hung anywhere that provided a good view. Operation centers were set up. Top Ecuadorean officials traveled to China for training, and Chinese engineers visited to teach their Ecuadorean counterparts how to work the system.

The activity attracted attention from Ecuador’s neighbors. Venezuelan officials came to see the system, according to a 2013 account from an Ecuadorean official working on the project. In an effort led by the onetime head of intelligence for Hugo Chávez, Venezuela then sprang for a larger version of the system, with a goal of adding 30,000cameras. Bolivia followed.

Beijing’s ambitions go much further than the abilities those countries bought. Today, the police across China gather material from tens of millions of cameras, and billions of records of travel, internet use and business activities, to keep tabs on citizens. The national watch list of would-be criminals and potential political agitators includes 20 million to 30 million people — more than Ecuador’s population of 16 million.

Chinese start-ups, backed in part by American investment, are competing to build methods for automated policing. They create algorithms that look for suspicious patterns in social media use and computer-vision software to track minorities and petitioners across cities. The spending spree has driven down prices for all types of policing gadgets, as varied as identity-card checkers and high-resolution security cameras.

In China, Ecuador’s project received praise. State media held it up as an example of a new China exporting advanced technology, instead of providing low-cost labor to assemble it.

In 2016, when President Xi visited Ecuador, he stopped by ECU-911 headquarters. Mr. Robayo said Mr. Xi had shown up for about five minutes, enough time for photo opportunities. The snapshots went up on C.E.I.E.C.’s website, a sign of official support from the most powerful Chinese leader in a generation.

He complained about police corruption. He argued that Mr. Correa’s government was complicit in Ecuador’s growing drug trade. He called out what he perceived as the administration’s incompetence.

Just as Mr. Chávez had done in Venezuela, Mr. Correa tightened the reins in Ecuador. He eliminated presidential term limits, intimidated and ejected judges, and sent henchmen to follow and attack political opponents and activists, like Mr. Pazmiño and Ms. Roldós.

“I think few people know about it or are actually aware of the huge power of ECU-911,” Ms. Roldós said. “There are few people who really know the extent of the tracking.” She added that Senain used just about any technology it could get its hands on to harass and follow Mr. Correa’s political opponents.

A seasoned intelligence officer, Mr. Pazmiño, 59, said even he was surprised when, in 2013, a video camera that was part of ECU-911 was installed directly outside his house. It hung from a pole on a traffic divider in the middle of the street, with a full view through a window into his second-story apartment.

“There is a direct collaboration between ECU-911, the Intelligence Secretariat and also those who surveil and persecute political or social actors,” said Mr. Pazmiño, citing his own experience, as well as documents and people who had worked in Senain.

Mr. Pazmiño said that after the camera went in, surveillance teams following him backed off. The camera otherwise made no real sense where it was. Mr. Pazmiño lives in a relatively safe neighborhood, and no other ECU-911 cameras were installed nearby. It was a move out of the police playbook in China, where cameras are positioned outside the doors of high-profile activists.

A visit to Senain’s headquarters confirmed Mr. Pazmiño’s suspicion. On a wall of screens that served as a sort of agency control room, Times reporters recognized footage from the ECU-911 system.

Mr. Costa, who was in charge of the transition between Senain and its successor, acknowledged the transmissions — but said he was not responsible for how they had been used in Mr. Correa’s administration.

Mr. Pazmiño said he had an idea of who should be held accountable: China. He said the country had supported and emboldened Mr. Correa, just as it had leaders in neighboring Venezuela. As conditions deteriorated in Venezuela last year, Huawei engineers helped train Venezuelan engineers on how to maintain their version of Ecuador’s system.

The crime has not subsided even though ECU-911 cameras arrived at the base of the hill several years ago. Ms. Rueda gestured to a pedestrian bridge there, where one man had grabbed her and threatened her with a knife while another had taken her money. The 2014 mugging happened directly beneath a police camera. No help came.

Ms. Rueda’s experience encapsulates the complex relationship many Ecuadoreans have with the cameras. While the authorities said the cameras had reduced crime, anecdotes of its dysfunction abound.

The odds are against Ecuador’s police force. Quito has more than 800 cameras. But during a Times visit, 30 police officers were on duty to check the footage. In their gray building atop the hill, officers spend a few minutes looking at footage from one camera and then switch. Preventing crime is only part of the job. In a control room, dispatchers supported responses to emergency calls.

It was a reminder that the system, and others like it, are more easily used for snooping than crime prevention. Following someone on the streets requires a small team, while large numbers of well-coordinated police are necessary to stop crime.

Mr. Robayo argued that ECU-911 had been responsible for a major drop in murders and an almost 13 percent drop in crime in 2018 from the previous year. The mere existence of a camera can also have a profound effect, he said.

Many Ecuadoreans agree. Despite Ms. Rueda’s mugging, she has called for the installation of more cameras in El Tejar. The best way to fix the neighborhood’s crime problems is to fix the surveillance system, she said.

Melissa Chan is a reporter focused on transnational issues, often involving China’s influence beyond its borders. Based in Los Angeles and Berlin, she is a collaborator with the Global Reporting Centre, and previously worked for Al Jazeera English in China, and Al Jazeera America covering the rural American West. @melissakchan

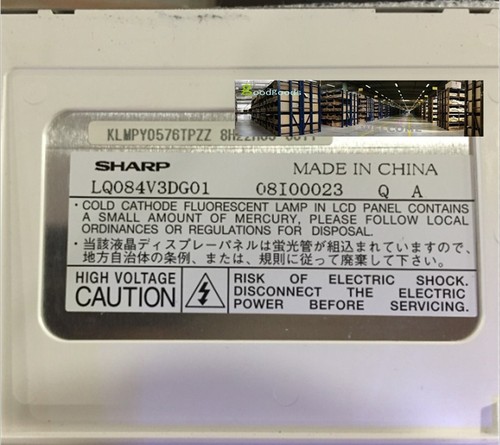

Oct 10 (Reuters) - The Biden administration published a sweeping set of export controls on Friday, including a measure to cut China off from certain semiconductor chips made anywhere in the world with U.S. equipment, vastly expanding its reach in its bid to slow Beijing"s technological and military advances.

The rules, some of which take immediate effect, build on restrictions sent in letters this year to top toolmakers KLA Corp (KLAC.O), Lam Research Corp (LRCX.O) and Applied Materials Inc (AMAT.O), effectively requiring them to halt shipments of equipment to wholly Chinese-owned factories producing advanced logic chips.

The raft of measures could amount to the biggest shift in U.S. policy toward shipping technology to China since the 1990s. If effective, they could hobble China"s chip manufacturing industry by forcing American and foreign companies that use U.S. technology to cut off support for some of China"s leading factories and chip designers.

"This will set the Chinese back years," said Jim Lewis, a technology and cybersecurity expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a Washington D.C.-based think tank, who said the policies harken back to the tough regulations of the height of the Cold War.

In a briefing with reporters on Thursday previewing the rules, senior government officials said many of the measures were aimed at preventing foreign firms from selling advanced chips to China or supplying Chinese firms with tools to make their own advanced chips. They conceded, however, that they had not secured any promises that allied nations would implement similar measures and that discussions with those nations are ongoing.

"We recognize that the unilateral controls we"re putting into place will lose effectiveness over time if other countries don"t join us," one official said. "And we risk harming U.S. technology leadership if foreign competitors are not subject to similar controls."

The expansion of U.S. powers to control exports to China of chips made with U.S. tools is based on a broadening of the so-called foreign direct product rule. It was previously expanded to give the U.S. government authority to control exports of chips made overseas to Chinese telecoms giant Huawei Technologies Co Ltd (HWT.UL) and later to stop the flow of semiconductors to Russia after its invasion of Ukraine.

On Friday, the Biden administration applied the expanded restrictions to China"s IFLYTEK, Dahua Technology, and Megvii Technology, companies added to the entity list in 2019 over allegations they aided Beijing in the suppression of its Uyghur minority group.

The rules published on Friday also block shipments of a broad array of chips for use in Chinese supercomputing systems. The rules define a supercomputer as any system with more than 100 petaflops of computing power within a floor space of 6,400 square feet, a definition that two industry sources said could also hit some commercial data centers at Chinese tech giants.

Eric Sayers, a defense policy expert at the American Enterprise Institute, said the move reflects a new bid by the Biden administration to contain China"s advances instead of simply seeking to level the playing field.

The Semiconductor Industry Association, which represents chipmakers, said it was studying the regulations and urged the United States to "implement the rules in a targeted way - and in collaboration with international partners - to help level the playing field."

Earlier on Friday, the United States added China"s top memory chipmaker YMTC and 30 other Chinese entities to a list of companies that U.S. officials cannot inspect, ratcheting up tensions with Beijing and starting a 60 day-clock that could trigger much tougher penalties. read more

Companies are added to the unverified list when U.S. authorities cannot complete on-site visits to determine if they can be trusted to receive sensitive U.S. technology, forcing U.S. suppliers to take greater care when shipping to them.

Under a new policy announced on Friday, if a government prevents U.S. officials from conducting site checks at companies placed on the unverified list, U.S. authorities will start the process for adding them to the entity list after 60 days.

Entity listing YMTC would escalate already-rising tensions with Beijing and force its U.S. suppliers to seek difficult-to-obtain licenses from the U.S. government before shipping them even the most low-tech items.

The new regulations will also severely restrict export of U.S. equipment to Chinese memory chip makers and formalize letters sent to Nvidia Corp (NVDA.O) and Advanced Micro Devices Inc (AMD) (AMD.O) restricting shipments to China of chips used in supercomputing systems that nations around the world rely on to develop nuclear weapons and other military technologies.

Reuters was first to report key details of the new curbs on memory chip makers, including a reprieve for foreign companies operating in China and the moves to broaden restrictions on shipments to China of technologies from KLA, Lam, Applied Materials, Nvidia and AMD.

South Korea"s industry ministry said in a statement on Saturday there would be no significant disruption to equipment supply for Samsung (005930.KS) and SK Hynix"s (000660.KS) existing chip production in China.

China"s commerce ministry said in a statement on Monday that it firmly opposes the U.S. move as it hurts the normal trade and economic exchange between companies in the two countries and threatens the stability of global supply chains.

On Saturday, China"s foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning called the move an abuse of trade measures designed to reinforce the United States" "technological hegemony". read more

On paper, it looked like a fantastic deal. In 2017, the Chinese government was offering to spend $100 million to build an ornate Chinese garden at the National Arboretum in Washington DC. Complete with temples, pavilions and a 70-foot white pagoda, the project thrilled local officials, who hoped it would attract thousands of tourists every year.

But when US counterintelligence officials began digging into the details, they found numerous red flags. The pagoda, they noted, would have been strategically placed on one of the highest points in Washington DC, just two miles from the US Capitol, a perfect spot for signals intelligence collection, multiple sources familiar with the episode told CNN.

Also alarming was that Chinese officials wanted to build the pagoda with materials shipped to the US in diplomatic pouches, which US Customs officials are barred from examining, the sources said.

The canceled garden is part of a frenzy of counterintelligence activity by the FBI and other federal agencies focused on what career US security officials say has been a dramatic escalation of Chinese espionage on US soil over the past decade.

Since at least 2017, federal officials have investigated Chinese land purchases near critical infrastructure, shut down a high-profile regional consulate believed by the US government to be a hotbed of Chinese spies and stonewalled what they saw as clear efforts to plant listening devices near sensitive military and government facilities.

Among the most alarming things the FBI uncovered pertains to Chinese-made Huawei equipment atop cell towers near US military bases in the rural Midwest. According to multiple sources familiar with the matter, the FBI determined the equipment was capable of capturing and disrupting highly restricted Defense Department communications, including those used by US Strategic Command, which oversees the country’s nuclear weapons.

While broad concerns about Huawei equipment near US military installations have been well known, the existence of this investigation and its findings have never been reported. Its origins stretch back to at least the Obama administration. It was described to CNN by more than a dozen sources, including current and former national security officials, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

It’s unclear if the intelligence community determined whether any data was actually intercepted and sent back to Beijing from these towers. Sources familiar with the issue say that from a technical standpoint, it’s incredibly difficult to prove a given package of data was stolen and sent overseas.

The Chinese government strongly denies any efforts to spy on the US. Huawei in a statement to CNN also denied that its equipment is capable of operating in any communications spectrum allocated to the Defense Department.

But multiple sources familiar with the investigation tell CNN that there’s no question the Huawei equipment has the ability to intercept not only commercial cell traffic but also the highly restricted airwaves used by the military and disrupt critical US Strategic Command communications, giving the Chinese government a potential window into America’s nuclear arsenal.

“This gets into some of the most sensitive things we do,” said one former FBI official with knowledge of the investigation. “It would impact our ability for essentially command and control with the nuclear triad. “That goes into the ‘BFD’ category.”

Former officials described the probe’s findings as a watershed moment. The investigation was so secret that some senior policymakers in the White House and elsewhere in government weren’t briefed on its existence until 2019, according to two sources familiar with the matter.

That fall, the Federal Communications Commission initiated a rule that effectively banned small telecoms from using Huawei and a few other brands of Chinese made-equipment. “The existence of the investigation at the highest levels turned some doves into hawks,” said one former US official.

But two years later, none of that equipment has been removed and rural telecom companies are still waiting for federal reimbursement money. The FCC received applications to remove some 24,000 pieces of Chinese-made communications equipment—but according to a July 15 update from the commission, it is more than $3 billion short of the money it needs to reimburse all eligible companies.

In late 2020, the Justice Department referred its national security concerns about Huawei equipment to the Commerce Department, and provided information on where the equipment was in place in the US, a former senior US law enforcement official told CNN.

After the Biden administration took office in 2021, the Commerce Department then opened its own probe into Huawei to determine if more urgent action was needed to expunge the Chinese technology provider from US telecom networks, the former law enforcement official and a current senior US official said.

That probe has proceeded slowly and is ongoing, the current US official said. Among the concerns that national security officials noted was that external communication from the Huawei equipment that occurs when software is updated, for example, could be exploited by the Chinese government.

Depending on what the Commerce Department finds, US telecom carriers could be forced to quickly remove Huawei equipment or face fines or other penalties.

“We cannot confirm or deny ongoing investigations, but we are committed to securing our information and communications technology and services supply chain. Protecting US persons safety and security against malign information collection is vital to protecting our economy and national security,” a Commerce Department spokesperson said.

US counterintelligence officials have recently made a priority of publicizing threats from China. This month, the US National Counterintelligence and Security Center issued a warning to American businesses and local and state governments about what it says are disguised efforts by China to manipulate them to influence US policy.

FBI Director Christopher Wray just traveled to London for a joint meeting with top British law enforcement officials to call attention to the Chinese threats.

In an exclusive interview with CNN, Wray said the FBI opens a new China counterintelligence investigation every 12 hours. “That’s probably about 2,000 or so investigations,” said Wray. “And that’s not even talking about their cyber theft, where they have a bigger hacking program than that of every other major nation combined, and have stolen more of Americans’ personal and corporate data than every nation combined.”

Asked why after years of national security concerns raised over Huawei, the equipment is still largely in place atop cell towers near US military bases, Wray said that, “We’re concerned about allowing any company that is beholden to a nation state that doesn’t adhere to and share our values, giving that company the ability to burrow into our telecommunications infrastructure.”

Despite its tough talk, the US government’s refusal to provide evidence to back up its claims that Huawei tech poses a risk to US national security has led some critics to accuse it of xenophobic overreach. The lack of a smoking gun also raises questions of whether US officials can separate legitimate Chinese investment from espionage.

“All of our products imported to the US have been tested and certified by the FCC before being deployed there,” Huawei said in its statement to CNN. “Our equipment only operates on the spectrum allocated by the FCC for commercial use. This means it cannot access any spectrum allocated to the DOD.”

“For more than 30 years, Huawei has maintained a proven track record in cyber security and we have never been involved in any malicious cyber security incidents,” the statement said.

In its zeal to sniff out evidence of Chinese spying, critics argue the feds have cast too wide a net — in particular as it relates to academic institutions. In one recent high-profile case, a federal judge acquitted a former University of Tennessee engineering professor whom the Justice Department had prosecuted under its so-called China Initiative that targets Chinese spying, arguing “there was no evidence presented that [the professor] ever collaborated with a Chinese university in conducting NASA-funded research.”

And on Jan. 20, the Justice Department dropped a separate case against an MIT professor accused of hiding his ties to China, saying it could no longer prove its case. In February, the Biden administration shut down the China Initiative entirely.

The federal government’s reticence across multiple administrations to detail what it knows has led some critics to accuse the government of chasing ghosts.

“It really comes down to: do you treat China as a neutral actor — because if you treat China as a neutral actor, then yeah, this seems crazy, that there’s some plot behind every tree,” said Anna Puglisi, a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. “However, China has shown us through its policies and actions it is not a neutral actor.”

As early as the Obama administration, FBI agents were monitoring a disturbing pattern along stretches of Interstate 25 in Colorado and Montana, and on arteries into Nebraska. The heavily trafficked corridor connects some of the most secretive military installations in the US, including an archipelago of nuclear missile silos.

For years, small, rural telecom providers had been installing cheaper, Chinese-made routers and other technology atop cell towers up and down I-25 and elsewhere in the region. Across much of these sparsely populated swaths of the west, these smaller carriers are the only option for cell coverage. And many of them turned to Huawei for cheaper, reliable equipment.

Beginning in late 2011, Viaero, the largest regional provider in the area, inked a contract with Huawei to provide the equipment for its upgrade to 3G. A decade later, it has Huawei tech installed across its entire fleet of towers, roughly 1,000 spread over five western states.

As Huawei equipment began to proliferate near US military bases, federal investigators started taking notice, sources familiar with the matter told CNN. Of particular concern was that Huawei was routinely selling cheap equipment to rural providers in cases that appeared to be unprofitable for Huawei — but which placed its equipment near military assets.

Federal investigators initially began “examining [Huawei] less from a technical lens and more from a business/financial view,” explained John Lenkart, a former senior FBI agent focused on counterintelligence issues related to China. Officials studied where Huawei sales efforts were most concentrated and looked for deals that “made no sense from a return-on-investment perspective,” Lenkart said.

By examining the Huawei equipment themselves, FBI investigators determined it could recognize and disrupt DOD-spectrum communications — even though it had been certified by the FCC, according to a source familiar with the investigation.

“It’s not technically hard to make a device that complies with the FCC that listens to nonpublic bands but then is quietly waiting for some activation trigger to listen to other bands,” said Eduardo Rojas, who leads the radio spectrum lab at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “Technically, it’s feasible.”

Around 2014, Viaero started mounting high-definition surveillance cameras on its towers to live-stream weather and traffic, a public service it shared with local news organizations. With dozens of cameras posted up and down I-25, the cameras provided a 24-7 bird’s eye view of traffic and incoming weather, even providing advance warning of tornadoes.

But they were also inadvertently capturing the movement of US military equipment and personnel, giving Beijing — or anyone for that matter — the ability to track the pattern of activity between a series of closely guarded military facilities.

The intelligence community determined the publicly posted live-streams were being viewed and likely captured from China, according to three sources familiar with the matter. Two sources briefed on the investigation at the time said officials believed that it was possible for Beijing’s intelligence service to “task” the cameras — hack into the network and control where they pointed. At least some of the cameras in question were running on Huawei networks.

In fact, DiRico first learned of government concerns about Huawei equipment from newspaper articles — not the FBI — and says he has never been briefed on the matter.

DiRico doesn’t question the government’s insistence that he needs to remove Huawei equipment, but he is skeptical that China’s intelligence services can exploit either the Huawei hardware itself or the camera equipment.

“We monitor our network pretty good,” DiRico said, adding that Viaero took over the support and maintenance for its own networks from Huawei shortly after installation. “We feel we’ve got a pretty good idea if there’s anything going on that’s inappropriate.”

By the time the I-25 investigation was briefed to the White House in 2019, counterintelligence officials begin looking for other places Chinese companies might be buying land or offering to develop a piece of municipal property, like a park or an old factory, sometimes as part of a “sister city” arrangement.

In one instance, officials shut down what they believed was a risky commercial deal near highly sensitive military testing installations in Utah sometime after the beginning of the I-25 investigation, according to one former US official. The military has a test and training range for hypersonic weapons in Utah, among other things. Sources declined to provide more details.

Federal officials were also alarmed by what sources described as a host of espionage and influence activities in Houston and, in 2020, shut down the Chinese consulate there.

US Attorney for the Eastern District of New York Richard P. Donoghue announcing indictments against China"s Huawei Technologies Co Ltd, several of its subsidiaries and its chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou on January 28, 2019.

Bill Evanina, who until early last year ran the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, told CNN that it can sometimes be hard to differentiate between a legitimate business opportunity and espionage — in part because both might be happening at the same time.

“What we’ve seen is legitimate companies that are three times removed from Beijing buy [a given] facility for obvious logical reasons, unaware of what the [Chinese] intelligence apparatus wants in that parcel [of land],” Evanina said. “What we’ve seen recently — it’s been what’s underneath the land.”

“The hard part is, that’s legitimate business, and what city or town is not going to want to take that money for that land when it’s just sitting there doing nothing?” he added.

After the results of the I-25 investigation were briefed to the Trump White House in 2019, the FCC ordered that telecom companies who receive federal subsidies to provide cell service to remote areas — companies like Viaero — must “rip and replace” their Huawei and ZTE equipment.

The FCC has since said that the cost could be more than double the $1.9 billion appropriated in 2020 and absent an additional appropriation from Congress, the agency is only planning to reimburse companies for a fraction of their costs.

DiRico, the CEO of Viaero, said the cost of “rip and replace” is astronomical and that he doesn’t expect the reimbursement money to be enough to pay for the change. According to the FCC, Viaero is expected to receive less than half of the funding it is actually due. Still, he expects to start removing the equipment within the next year.

Some former counterintelligence officials expressed frustration that the US government isn’t providing more granular detail about what it knows to companies — or to cities and states considering a Chinese investment proposal. They believe that not only would that kind of detail help private industry and state and local governments understand the seriousness of the threat as they see it, but also help combat the criticism that the US government is targeting Chinese companies and people, rather than Chinese state-run espionage.

“This government has to do a better job of letting everyone know this is a Communist Party issue, it’s not a Chinese people issue,” Evanina said. “And I’ll be the first to say that the government has to do better with respect to understanding the Communist Party’s intentions are not the same intentions of the Chinese people.”

A current FBI official said the bureau is giving more defensive briefings to US businesses, academic institutions and state and local governments that include far more detail than in the past, but officials are still fighting an uphill battle.

“Sometimes I feel like we’re a lifeguard going out to a drowning person, and they don’t want our help,” said the current FBI official. But, this person said, “I think sometimes we [the FBI] say ‘China threat,’ and we take for granted what all that means in our head. And it means something else to the people that we’re delivering it to.”

As U.S.-China tensions rise and news and developments regarding the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and U.S.-China relations are never far from the headlines, the interest in and necessity to better understand China and the Chinese government’s perspective continues to increase.

Below, Brookings experts offer recommendations and thoughts on where to find official Chinese government documents, in Chinese and English, as well as reliable information and analysis on Beijing’s perspectives and policies, and what they read to gain insight into contemporary China.

My work has focused on China’s policy towards and relations with some of its neighbors — particularly Taiwan but also Hong Kong and Japan. I am most interested in China’s actions, but must also consider the motivations behind those actions.

In documenting China’s actions, I can usually rely on the targets of those actions to expose them, through government statements and local media coverage. For the Chinese public side of the story, as Beijing wants it understood, government agencies (such as the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and the official media (like People’s Daily) are usually reliable. The pattern of the actions themselves can reveal a lot about motivations.

Because the PRC regime controls much of the media and also uses the media to justify its actions and shape the perceptions of outsiders, there are obvious limits on its utility. Yet the regime has long institutionalized its approach to messaging. Any official policy statement is the product of a formal decisionmaking process that takes account of changes in the policy environment and uses text to signal policy changes. For example, past Chinese leaders, in talking about what elements of Taiwan’s system would remain after unification, consistently said that Taiwan could keep its armed forces. But President Xi Jinping, in his authoritative speech on Taiwan on January 2, 2019, did not repeat that point. We can be sure that this was not a drafting error; it was the product of a deliberate decision that suggests a significant change in PRC policy.

Similarly, because some PRC media serve a propaganda purpose, changes in subject and content reflect how the regime would like readers to change their understanding of Chinese policy. Moreover, the subjects that do not get covered can be as revealing as those that do.

When it comes to Taiwan (and to Hong Kong to a much lesser extent), there is a unique source of commentary regarding developments in Taiwan, the rationale for PRC policy, and the regime’s aspirations for the future. This is the monthly Hong Kong journal Zhongguo Pinglun (China Review). It is an important outlet for PRC scholars who specialize on Taiwan. It is a place where they can publish their views regularly and with more elaboration than is possible within China itself. It features authors from Beijing, Shanghai, other cities in China, and a few scholars in Taiwan whose views on cross-Strait relations are more friendly to China (or at least not seen as hostile). Of course, the journal serves a propaganda purpose, but it does reveal the permissible range of views on Taiwan matters and is by far the most convenient way to keep up on how the PRC regime wants readers to view Taiwan and Beijing’s policy towards it.

My research focuses on the Chinese economy and China’s economic interactions with other countries, especially the U.S. and China’s Belt and Road Initiative partners. The best source of macroeconomic data on China is the International Monetary Fund (IMF), especially the annual Article IV report and the China section of global reports such as the “World Economic Outlook.”The IMF works from official data, but makes various adjustments and explains certain nuances that are very helpful. For microeconomic data such as measures of inequality and poverty or sectoral output, the World Bank plays a similar role. China’s official data is published on the websites of its main economic ministries, the National Bureau of Statistics, the People’s Bank of China, the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Commerce. There are other specialized sources that fill particular niches. The Bank for International Settlement publishes times series of China’s trade-weighted exchange rate and measures of leverage (government debt or corporate debt relative to GDP). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) calculates a foreign investment restrictiveness index sector by sector for OECD economies and some major emerging markets such as China. Concerning international trade and investment between China and the U.S., the U.S. Bureau of the Census publishes detailed and up-to-date data. For the activities of the Belt and Road Initiative, there are two useful academic efforts: AidData at William & Mary and the China-Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies collect and publish information on China’s overseas lending and investment.

As competition between the United States and China intensifies, it is becoming all the more important for American policymakers, experts, and the public to accurately understand Beijing’s ambitions, as well as its strengths and weaknesses in pursuit of its goals. This task is becoming more difficult due to COVID-19-induced limits on travel and Chinese government-imposed curbs on civil society, journalists, academics, and experts to conduct in-country research.

I generally am cautious in accepting the findings of American experts who use texts selectively to support their preferred narratives about China. Many speech transcripts, op-eds, and reports published by government agencies or government-affiliated think tanks are in conversation with one another. Different interest groups often use these platforms to push their policy preferences, e.g., taking a more assertive foreign policy posture, strengthening support for specific military programs, or increasing funding for social safety net programs. To view statements around these types of issues in isolation, or to draw only from sources who support a common view on these types of questions, would be to miss critical context for understanding the nature of debate.

Similarly, warning flags fly whenever Western scholars publish research suggesting that all Chinese voices are in accord on a specific policy, goal, or national objective. While it cannot credibly be argued that China’s media environment is a flourishing laboratory of independent ideas, it also often strains credulity to suggest Chinese discourse on charged political issues is monolithic. The truth most often is messier.

With that as context, I try to read a range of commentaries from authoritative Chinese media outlets, including Xinhua, People’s Daily, and Reference News. I also try to follow major announcements, speeches, and trips by monitoring the website of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. China’s main TV outlet, CCTV, does a helpful job with its nightly news program of highlighting the most important events that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership wants Chinese people to follow. Major Chinese think tanks (for example, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the China Institute of International Studies, and the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations) often release reports about policy issues, which help serve as a guide to issues under debate. I also pay attention to Global Times — which I view as a distant Chinese cousin of Fox News given its enthusiasm for stoking nationalism and outrage — to get a sense of issues that are animating emotions inside China.

When reviewing these sources, omissions occasionally are as important as issues that receive emphasis. Deliberate omissions of elements of the leadership’s policy catechism can signal absence of support for a specific policy direction, for example.

Ultimately, though, the best insights I gain about debates and developments inside China often arise from exchanges with Chinese counterparts, whether in person, via email, or via Zoom. My Chinese counterparts understand the issues and the players involved in debates in ways I never will, just as I understand the nature of public debates in the United States in ways that are not intuitive to them. Not everything my Chinese counterparts tell me about internal developments can be taken at face value, so a dose of skepticism and access to a range of viewpoints often are needed to develop a composite picture. All that said, regularly exchanging perspectives with Chinese counterparts remains crucial to my understanding of how China operates.

In my China regulatory and legal work, I mainly rely on primary Chinese documents, supplemented by analytic and some academic sources. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and official Chinese state authorities identified in China’s constitution — other than the Central Military Commission and the State Supervision Commission, which is essentially part of the CCP Central Discipline Inspection Commission — post many official documents, including drafts released for public comment in some instances, on their official Chinese-language websites and social media accounts. WeChat and social media have become an almost indispensable source of keeping up on new policies, legislation, and developments.

Some central ministries that deal with foreign policy, commercial, financial, and other foreign-related affairs also maintain English-language websites that are typically less complete than the Chinese-language ones. Even seemingly official English translations published by the authorities need to be used carefully, and checked against the original Chinese text, as various important terms are often translated differently in different documents. Jeremy Daum’s collaborative translation project, China Law Translate, provides rapid, free translations of and commentary on an array of Chinese legal developments, and several professional and specialized organizations — like Graham Webster’s DigiChina Project that translates and analyzes Chinese technology policy — and publishers offer free or for-fee translations of select Chinese policy and legal documents.

The Chinese Communist Party publishes selected speeches by CCP leaders, decisions, plans, policies, intraparty regulations, reports, and other documents relating to its meetings and activities. It does not maintain an English-language website. Some CCP subordinate organizations like the anti-corruption Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the Political-Legal Committee have their own websites. The Center for Advanced China Research’s Party Watch Weekly Report offers updates and information on CCP activities in English.

The National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee publish a host of documents including laws, draft laws, and official and academic commentaries on laws; five-year and annual legislative plans; annual work reports submitted by other state organs for approval at the annual NPC meeting; and congressional supervision investigation reports. It also maintains an English-language website with translations of many laws. The NPC Observer, run by Changhao Wei, offers commentary, compilations, and explanations concerning the NPC in English. Local people’s congresses at the provincial, county, and township levels also publish locally-promulgated and issued documents.

The State Council, China’s central government, also publishes CCP and government policy documents, economic and rulemaking plans, administrative regulations in draft and final forms, regulatory documents, white papers, statistics, and other materials, some of which are available in translation on its English-language website. Most ministries and other institutions subordinate to the State Council also maintain websites to publish their own documents, as do local governments and their departments. Some of these, such as the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Commerce, and Finance, also maintain English-language websites. Many newsletters like Trivium Tip Sheet and CP.China Policy follow State Council policies, regulations, and regulatory activities.

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC), and its English-language website, now publishes many of its and the lower courts’ judicial decisions in a searchable, open database, as well as judicial interpretations, judicial reform and annual judicial interpretation plans, investigations, and other reports and analyses. Susan Finder maintains a helpful blog, Supreme People’s Court Monitor, which discusses the courts. The Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP) is responsible for legal prosecution and investigation in China. It also publishes a variety of documents including prosecution-related policies, guidelines, rules, and case reports. It does not maintain an English-language website.

English-language newspapers and magazines offer great coverage of China. In addition to usual outlets — The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Economist, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, etc. — Caixin Global (whose content is taken from their broader Chinese-language counterpart) and the South China Morning Post are good sources of news and analysis of China developments. Sixth Tone features stories about Chinese society. The China Daily is the official English-language newspaper of the Chinese government and publishes official documents in English translation from time to time, as does Xinhua (the state run press agency) English-language service.

I work on security and foreign policy issues, so I usually rely on the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of National Defense websites and the People’s Liberation Army services’ and theater commands’ WeChat accounts to follow events. CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) and Pishu are my go-to databases for most Chinese-language newspaper and journal articles, yearbooks, and think tank reports. For English-language sources, I usually look at reports and analyses coming out from Brookings, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, RAND Corporation, CNA, National Defense University, the National Bureau of Asian Research, the Center for a New American Security, the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, the U.S. Naval War College, and articles published in major academic and policy journals. I also follow information released by Japan’s Ministry of Defense and its research institution the National Institute for Defense Studies, the Japan Coast Guard, and several Japanese think tanks, including the Japan Institute for International Affairs, Sasakawa Peace Foundation, and the Institute of Developing Economies. In addition, I follow content published by several Singapore-based institutions including the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) of the Nanyang Technological University and the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey