arduino lcd display clock made in china

While I was looking for a TFT display for a project with Arduino, I found on several webstores some displays based on the ST7735 chip by Sitronix (datasheet).

Based on its datasheet, the ST7735 chip has a SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) interface, but the pin names on the silk screen of my display “seem” to suggest an I2C interface (SDA, SCL…):

First identify – based on your Arduino board – which pins correspond to the different signals of the SPI bus. For the others, you can freely choose between the remaining pins.

(as you see, I connected the BLK pin directly to Vcc to have the backlight always on. You can also connect it to an Arduino digital pin to be able to control the backlight via software, for example if you need to save power).

Adafruit wrote a fantastic tutorial to explain how to use them, here I only want to show you how to setup the display for the connections I made earler:

If you’re using a board based on the esp32 chip and you need to display bitmap images, give a look to my library, SPIFFS_ImageReader, which perfectly integrates with the ones by Adafruit!

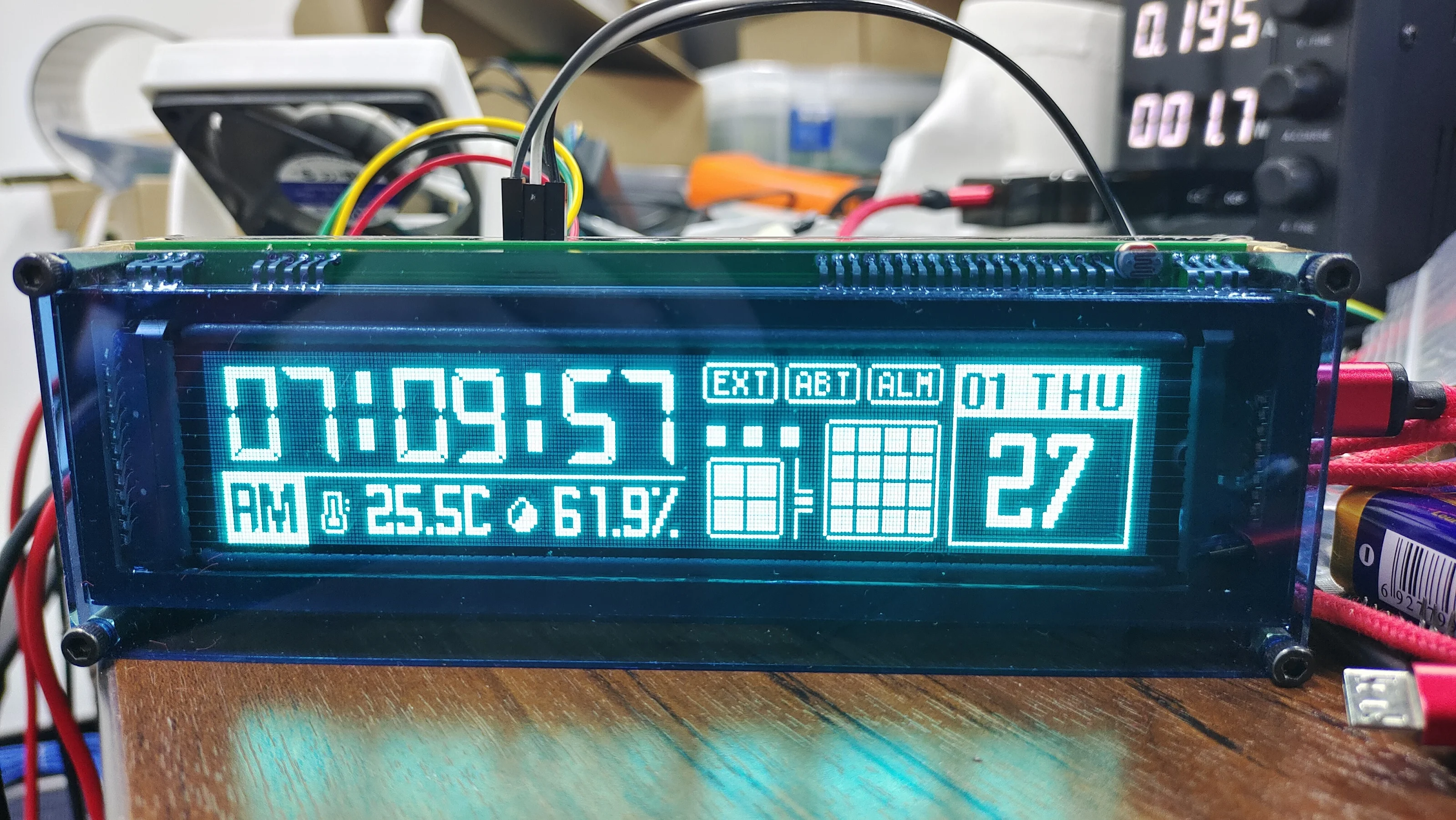

This is yet another Arduino LCD clock, but with a twist; this clock knows some holidays and birthdays, and can make calculations on the fly of how old someone is and then display the information on the LCD screen. I was inspired to make this clock because two dear friends had a big birthday party and asked for "only stories" as gifts. This clock continually updates the story of their time together.

The clock can obtain power from a USB cord, 2 D cell batteries, or a wall wart (input 7-12 volts 500mA). It will run for about 2-3 months on the D-cells so that is not the optimal power supply. The color of the LCD backlight can be changed.

This is my second Instructable, and like the first one (a personality tester), it is designed for people like me; beginners with Arduino microcontrollers but who have some rudimentary woodworking skills. This Instructable is essentially divided into two parts; how I made the electronics and how I made the enclosure.

a box to hold the clockI used some burled maple plywood leftover from a different project and some scrap redwood for the legs and top. You could use a cigar box or almost any box you liked from a thrift store. I will explain how I made my enclosure later in this Instructable.

There are two thick copper wire bands on the front of the clock. Touch the one on the left (as you face the clock) and it displays information about one person. Touch the copper wire on the right and another person"s information is displayed. Press both wires at the same time and information about their combined time together is displayed.

To set the time, the back of the clock has a variety of copper sensor wires. Changing the time involves simultaneously touching the appropriate copper wires on the back of the clock – for example to set the minutes back by 5, simple touch the minutes wire and then tap the minus wire 5 times, once per second. The clock is set up to only advance the time by one unit per second, so if you need to set the clock ahead 30 minutes it will take 30 seconds of holding the wires. Setting the year requires simultaneously touching three wires; the month and day wires and then the plus or minus wire.

The battery on/off is useful for saving batteries and for resetting the clock. This should be switched off when the clock receives power from a wall wart or from USB. Two 10k-ohm potentiometers control the LCD brightness and color.

There are the two parts that "talk" to the Arduino using I2C; the clock and the cap1188 sensor breakouts. I wired the clock first to pins A4 and A5 of the Arduino. Then I "daisy chained" the cap1188 breakout board in by wiring it to the SDA and SCK outs from the clock breakout board (essentially they are wired in parallel).

There are two 10k-ohm potentiometers for controlling the backlighting color and contrast. They get 5v and ground to the outer posts (doesn"t matter which side gets what) and the center posts go to either A3 of the Arduino or to pin 3 of the LCD screen.

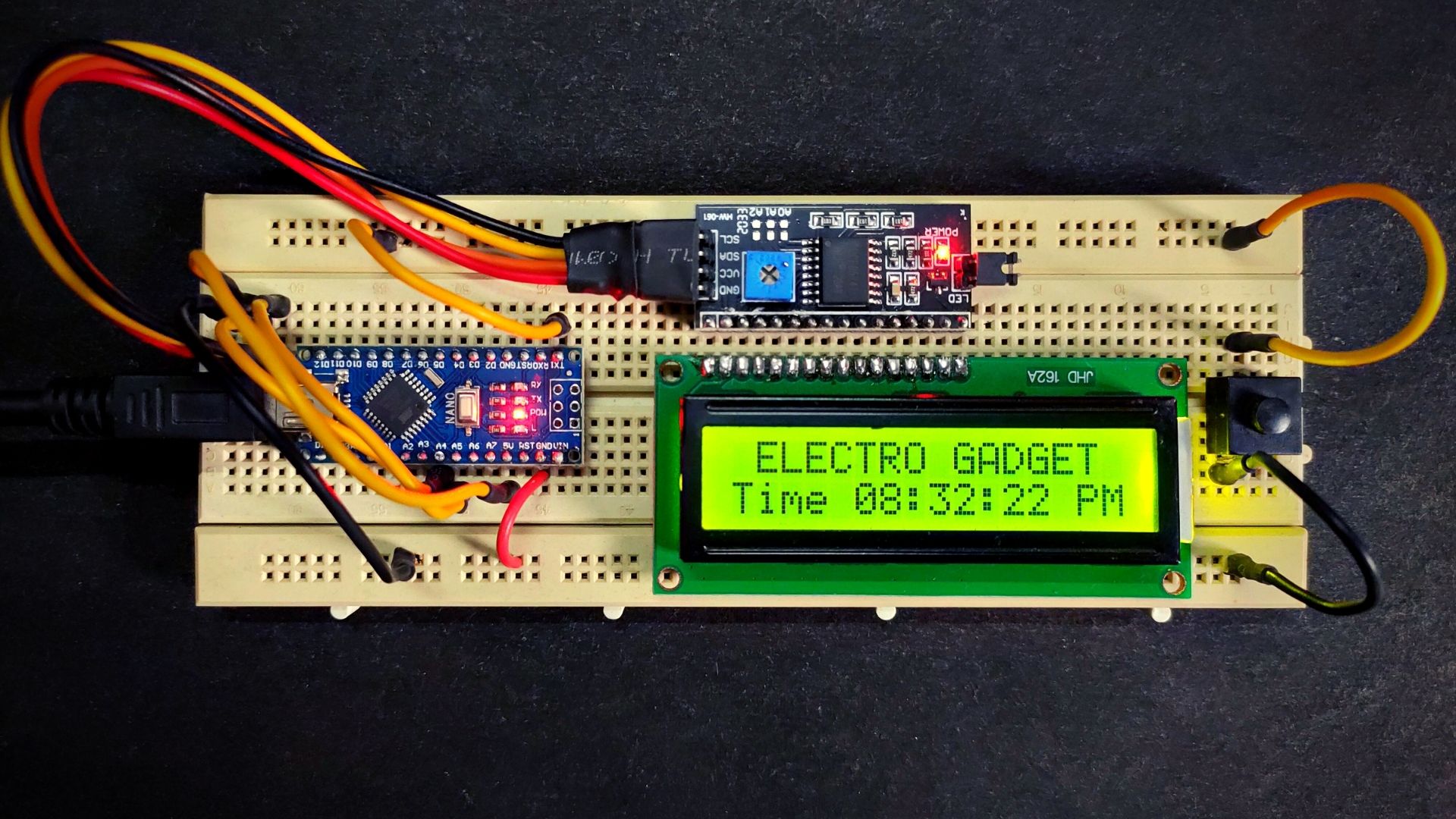

As usual, I bought enough components to make one clock on the breadboard and another "for real". Thus, I had a working breadboarded version to look at as I wired up the real one into the clock enclosure.

Download the Arduino code here and then open it in the Arduino editor (I wrote it using version 1.6.3). You will include a couple standard libraries (wire.h and LiquidCrystal.h) and SPI.h is included (but I don"t think I used it, it is legacy from the original code I cobbled together to make the clock).

You will also need two special libraries. I have placed them here for download only because I wanted you to have the exact versions I used (so everything will work). However, I strongly suggest that you seek out the original files from Adafruit (Cap1188) and from David H Brown (for the real time clock library) because they might get updated and because these people put in a great deal of effort making these libraries for people like us.

The capacitance sensor determines what should happen, so check to see if it has been touched.Cap Touched?NO = display the time on the top lineCheck if it is a birthday or some other special day?YES = display a special message on the 2nd line

For example, if the 5th wire is touched, the Arduino "sees" the number 16. Further, suppose that the 3rd wire and 6th wires are touched at the same time, the Arduino would see the number 36. Why? because the wires attached to the capacitance sensor are numbered from 0-7 and the 3rd wire has the number 2^2=4 and the 6th wire has the number 2^5=32 and the sum of the two numbers is 4+32=36.

So, with 8 wires attached to the capacitance sensor, we can have lots of different combinations [(2^8)-1 = 255 combinations] to do different things. I only coded the clock for 13 different things. They are: something about person 1, something about person 2, something about them together, plus hours, minus hours, plus minutes, minus minutes, plus days, minus days, plus months, minus months, plus years, and minus years.

If you look at the Arduino code you will see where I have the Arduino check for the different combinations that have meaning. Each little snippet like this one:

The clock has this nifty (at least I think it is nifty) feature where if you touch one of the wires on the front of the clock, it calculates how old the clock owner is and displays it in either years, months or days. The math is pretty simple, but if you haven"t done math using an Arduino, here is a little guidance. As with the previous step, skip this if you are already an expert.

The picture above is of the "calcs" subroutine. It will calculate and store the age of the two clock owners into 6 different integers, and also calculate how long they have been together (3 integers). It works like this:Is it before or after Ruth"s birthday this year?After: calculate her age as 35 + years (where 35 is how old Ruth was on this date back in the year 2000, and "years" is what year it is now)

Before: calculate her age as 34 + years (because her birthday hasn"t arrived yet this year).Store this calculation as an integer called "ruth_y" (you should change this to the name of the person you are making your clock for)

It works like this: set the "dates" number ahead by 1, then set the clock, then delay for 1/2 a second before doing it again. Two things to note: You have to set the thing you are setting and then set the clock (e.g. have the two statements in there together and in the right order). If you have them in the wrong order, or if you omit the setClock(); statement, it won"t work. Second, the 1/2 second delay is in there to keep the clock from adding lots and lots of time from a brief touch of the wires.

There are two ways to initially get the clock going.Use a separate program to start the clock. That is what I did - below is a link for you to download the little program I used. You set the time in the program and run it once.

Or you can simply temporarily add one line of code to the main program at the very beginning of the void loop. Add this: start clock(); then run the program once and it should say that it is 00:00:00 on Jan 1 2000. Then comment out the line, run the program again, and use the buttons on the back of the clock to set the time. This will be slow.

You can use most anything as an enclosure - I am building one using a cigar box, but for this project my enclosure was constructed from some scrap 1/4 inch particle board that has a nice maple burl veneer on one side. I cut it so that a 4 D-cell battery holder would fit inside (I wound up using only a 2-battery holder) and made the depth of the box slightly larger than the Arduino. I test-fit it several times, then measured for the placement of the LCD screen. I drilled a set of holes and then used a file to slowly shape the rectangular hole so that the LCD screen fit into it snugly.

At this point I realized that I needed holes for the Arduino USB and power cables. Too late! It was already glued up. So I cut them by hand, and if you look at the pictures you can see that this mistake led to the veneer peeling on those cuts. It looks poor; luckily it is on the back of the clock and not the front.

The lid for the clock is another piece of scrap redwood. I also cut two small pieces of wood to form rails to hold it to the clock. Imagine an upside-down railroad track. The lid is held in place by friction and a brass screw on the back side that holds one of the rails to the clock. I then sanded the entire thing so it was smooth. I sprayed it all with shellac, several coats, and then let it all dry. Time to add the electronics!

I also drilled two holes for the 10k potentiometers and soldered wires to them. Finally, I drilled a hole for the on/off switch. At this point the clock was just a mess of wires sticking out the top of the enclosure with no electronics inside.

I used an ice pick to "pre-drill" some small holes in the box and then screwed the Arduino and the RTC clock boards in place. I wired that all up to the Arduino then added the cap sensor and wired that up last. I did it that way because I was lazy and didn"t feel like making more small holes for the cap sensor to be screwed to the inner walls of the clock enclosure. It simply sits atop all the wires.

Lastly I soldered the battery booster to the 2 D-cell battery pack, wired it up and shoved it in the bottom of the clock. It is held in place by friction and a small scrap of wood that I glued to the bottom. I should have thought that part through more, but oh well, it works fine and nobody can see it unless they actively look.

I really enjoyed building this clock for our friends, and I will build one for my own family. Simple things I will add will be more holidays and family birthdays, and I"ll probably add a buzzer alarm and a little light sensor to automatically turn the brightness down at night. There are lots of tutorials here on Instructables for adding these things and now that I am a little familiar with the real time clock library, adding more functionality should be within my grasp.

The 1637 part takes about 75ms per digit to write to on a nano. That is S L O W. They’re fine for clocks but not for anything with much else going on.

These go in all my temp projects, the gps test clock, the portable lux meter, the square wave clock generator, the rf24 transmitter and receiver test fixtures, etc. They’re a little small for across-the-room viewing but are 1/4th the price of the Adafruit units.

DS3231 is a low-cost, extremely accurate I2C real-time clock (RTC), with an integrated temperature-compensated crystal oscillator (TCXO) and crystal. The device incorporates a battery input, disconnects the main power supply and maintains accurate timekeeping. Integrated oscillator improve long-term accuracy of the device

RTC maintains seconds, minutes, hours, day, date, month, and year information. Less than 31 days of the month, the end date will be automatically adjusted, including corrections for leap year. The clock operates in either the 24 hours or band / AM / PM indication of the 12-hour format. Provides two configurable alarm clock and a calendar can be set to a square wave output. Address and data are transferred serially through an I2C bidirectional bus.

Hey, hello everyone. I’m Gary Lu, a geek from China. In this passage I will show you how to design and build an air quality monitor with some simple parts. With different kits, you can also add some other functions you want, like an alarm function or else. I have a hydrogen and a CO monitor, so this sample will be used to monitor these two kinds of common explosive gas. What’s is more fantastic is that apart from displaying the results on a LCD screen, it will also save the results and the time in a SD card you plug in the board. OK, without further ado, let’s start.

Tutorial: 1. Connect the parts: First you need to plug the IO expansion shield on the Arduino board; and then connect the expansion board, clock module and the LCD screen, then plug the SD module on the expansion board. Attach the buzzer on to the digital pin 4 on the expansion board. Then attach the hydrogen sensor and the CO sensor on the analog pin 0 and pin 1. And it is a necessary knowledge that when attaching them the black wire means the ground, red for the power, green for the digital signal and blue for analog. Be careful when connecting. And the diagram is as shown below.

Pay attention when connecting the expansion board and the clock module, the pin order on the expansion board is (vcc, GND, SCL, SDA). So it necessary for you to repack your IIC cable. After connecting them all, I power it with a 12V adaptor, but the LCD screen doesn’t work well. After checking the board, I found out it was because of the sensors. The sensors need to be heated while working and only one adaptor is far from enough. So I make a new power with a 5V adaptor and a self-made USB cable. After attaching it on the analog pin 3, everything turns out well. OK, here is the final effect:

2. Software Libraries? In this sample we will only use the Arduino IDE as our writing software. You can download it from the official web site of Arduino. And we will use two extra libraries in total, one is for the LCD screen and another is for the clock module. You can download it from the wiki page of these two products. After downloading the libraries. You need to put the library files into your Arduino-1.0.x/libraries folder. After doing this, you can open the Arduino IDE and kick on the Sketch-Import library to check in whether you have setup the library successfully. Function preparing? As we all know, the message an analog pin can read is a round number from 0 to 1023, and it is the same with the analog gas sensor. So how can we change this number into the real content of the gas we want to know? To do this, we have to understand the principle of the gas sensor we use. The sensor we used is the MQ serial sensor. Log on their official website and we can figure out the theory. Let’s take the hydrogen sensor as an example. The following is the schematic.

Supper Accurate Digital Clock Using GPS & P10 Display: A brief history of time Improving the precision and accuracy of timekeeping has been a goal since ancient Egyptians and Ch...

We have used Liquid Crystal Displays in the DroneBot Workshop many times before, but the one we are working with today has a bit of a twist – it’s a circle! Perfect for creating electronic gauges and special effects.

LCD, or Liquid Crystal Displays, are great choices for many applications. They aren’t that power-hungry, they are available in monochrome or full-color models, and they are available in all shapes and sizes.

Today we will see how to use this display with both an Arduino and an ESP32. We will also use a pair of them to make some rather spooky animated eyeballs!

Waveshare actually has several round LCD modules, I chose the 1.28-inch model as it was readily available on Amazon. You could probably perform the same experiments using a different module, although you may require a different driver.

There are also some additional connections to the display. One of them, DC, sets the display into either Data or Command mode. Another, BL, is a control for the display’s backlight.

The above illustration shows the connections to the display. The Waveshare display can be used with either 3.3 or 5-volt logic, the power supply voltage should match the logic level (although you CAN use a 5-volt supply with 3.3-volt logic).

Another difference is simply with the labeling on the display. There are two pins, one labeled SDA and the other labeled SCL. At a glance, you would assume that this is an I2C device, but it isn’t, it’s SPI just like the Waveshare device.

This display can be used for the experiments we will be doing with the ESP32, as that is a 3.3-volt logic microcontroller. You would need to use a voltage level converter if you wanted to use one of these with an Arduino Uno.

The Arduino Uno is arguably the most common microcontroller on the planet, certainly for experiments it is. However, it is also quite old and compared to more modern devices its 16-MHz clock is pretty slow.

The Waveshare device comes with a cable for use with the display. Unfortunately, it only has female ends, which would be excellent for a Raspberry Pi (which is also supported) but not too handy for an Arduino Uno. I used short breadboard jumper wires to convert the ends into male ones suitable for the Arduino.

Once you have everything hooked up, you can start coding for the display. There are a few ways to do this, one of them is to grab the sample code thatWaveshare provides on their Wiki.

The Waveshare Wiki does provide some information about the display and a bit of sample code for a few common controllers. It’s a reasonable support page, unfortunately, it is the only support that Waveshare provides(I would have liked to see more examples and a tutorial, but I guess I’m spoiled by Adafruit and Sparkfun LOL).

Open the Arduino folder. Inside you’ll find quite a few folders, one for each display size that Waveshare supports. As I’m using the 1.28-inch model, I selected theLCD_1inch28folder.

Once you do that, you can open your Arduino IDE and then navigate to that folder. Inside the folder, there is a sketch file namedLCD_1inch28.inowhich you will want to open.

When you open the sketch, you’ll be greeted by an error message in your Arduino IDE. The error is that two of the files included in the sketch contain unrecognized characters. The IDE offers the suggestion of fixing these with the “Fix Encoder & Reload” function (in the Tools menu), but that won’t work.

You can see from the code that after loading some libraries we initialize the display, set its backlight level (you can use PWM on the BL pin to set the level), and paint a new image. We then proceed to draw lines and strings onto the display.

Unfortunately, Waveshare doesn’t offer documentation for this, but you can gather quite a bit of information by reading theLCD_Driver.cppfile, where the functions are somewhat documented.

After uploading the code, you will see the display show a fake “clock”. It’s a static display, but it does illustrate how you can use this with the Waveshare code.

This library is an extension of the Adafruit GFX library, which itself is one of the most popular display libraries around. Because of this, there isextensive documentation for this libraryavailable from Adafruit. This makes the library an excellent choice for those who want to write their own applications.

As with the Waveshare sample, this file just prints shapes and text to the display. It is quite an easy sketch to understand, especially with the Adafruit documentation.

The sketch finishes by printing some bizarre text on the display. The text is an excerpt from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, and it’s a sample of Vogon poetry, which is considered to be the third-worst in the Galaxy!

Here is the hookup for the ESP32 and the GC9A01 display. As with most ESP32 hookup diagrams, it is important to use the correct GPIO numbers instead of physical pins. The diagram shows the WROVER, so if you are using a different module you’ll need to consult its documentation to ensure that you hook it up properly.

The TFT_eSPI library is ideal for this, and several other, displays. You can install it through your Arduino IDE Library Manager, just search for “TFT_eSPI”.

There is a lot of demo code included with the library. Some of it is intended for other display sizes, but there are a few that you can use with your circular display.

To test out the display, you can use theColour_Test sketch, found inside the Test and Diagnostic menu item inside the library samples. While this sketch was not made for this display, it is a good way to confirm that you have everything hooked up and configured properly.

A great demo code sample is theAnimated_dialsketch, which is found inside theSpritesmenu item. This demonstration code will produce a “dial” indicator on the display, along with some simulated “data” (really just a random number generator).

One of my favorite sketches is the Animated Eyes sketch, which displays a pair of very convincing eyeballs that move. Although it will work on a single display, it is more effective if you use two.

The first thing we need to do is to hook up a second display. To do this, you connect every wire in parallel with the first display, except for the CS (chip select) line.

The Animated Eyes sketch can be found within the sample files for the TFT_eSPI library, under the “generic” folder. Assuming that you have wired up the second GC9A01 display, you’ll want to use theAnimated_Eyes_2sketch.

The GC9A01 LCD module is a 1.28-inch round display that is useful for instrumentation and other similar projects. Today we will learn how to use this display with an Arduino Uno and an ESP32.

A lcd display is an effective and economic means to visually present data collected by an Arduino. On the market is a great variety of lcd displays. Most common are monochrome displays capable of presenting two lines with each 16 characters (16×2) and displays that show four lines with each 20 characters (20×4). Here we will discuss the basics of connecting a 16×2 lcd display to an Arduino. After that we will connect a Dallas DS18B20 temperature sensor to the Arduino with the purpose to display sensor data. Simple sketches are provided at successive stages while we will walk through each sketch.

Data collected with a sensor connected to an Arduino can be presented in many ways. They can be displayed on your computer via Serial Monitor, transmitted to another Arduino or even to a server on the internet to have them available for final display on your smartphone, tablet or any other suitable platform. An elegant, maybe the ‘historical’ way that is very useful in standalone situations, is to use a display of some sorts connected directly to the Arduino board. Most common today are displays based on lcd, OLED or TFT technology. I assume that lcd displays were the first made available to the Arduino community. Most are compatible with the de facto Hitachi HD44780 standard. Many manufacturers, mostly Chinese, are flushing the market with affordable lcd displays ready to be connected with an Arduino.

Figure 1: Front view of a classic, China made 16×2 lcd display ready to connect with an Arduino. The pin interface has 16 pins numbered 1 to 16. On some displays (like this one) connectivity code is printed onto the printed circuit board. Note that the 220 Ω resistor between 5V and pin 15 is necessary to reduce the voltage to the backlight led to 3.3V.

Such displays are available in various tastes, colors and numbers of characters that can be displayed. As this is a ‘basic’ paper, I will discuss here the 16×2 monochrome display (two lines of 16 characters each) because I regard this device as the ‘mother of all lcd displays’. They are perfect for the beginner and they may as well perfectly serve needs of more advanced Arduino hobbyists. Many permanent projects can be equipped with a lcd display to provide visual information, for instance digital clocks and timers, water temperature control devices, moisture sensor devices, tachometers, barometers, complete weather stations, etcetera.

Pin 3 of the display must be connected with the middle contact, named in jargon the ‘’wiper’, of a 10 kΩ potentiometer. Only one of the other two pins of the potentiometer must be connected to GND. You can ignore the other pin. This pot meter supplies a voltage to the display that adjusts the contrast of the characters against the (fixed illumination) background. Power for the background illumination is supplied via pins 15 and 16 of the display. Background illumination is achieved with a white led and a diffuser. The diffuser sticks out on the side of the display (figure 1). As leds are typically 3.3V devices, a 220 Ω resistor is needed in series at pin 15 to protect the backlight led from receiving too much power.

As the potentiometer is only needed to fine-tune the contrast one can experiment to connect pin 3 via a resistor with a fixed value with GND of the Arduino. Begin the experiments with a 10 kΩ resistor and replace it stepwise with one with a lower value until a satisfactory contrast is achieved. With the display shown in figures 1 and 2 a 470 Ω resistor sufficed.

Data from the Arduino to be displayed on the lcd display run via pins 11,12,13 and 14 of the display. Display pin 11 is connected with pin 5 of the Arduino, display pin 12 with pin 4 of the Arduino, display pin 13 with pin 3 of the Arduino, and display pin 14 with pin 2 of the Arduino.

Once the proper pins of the lcd display are connected with the proper pins of the Arduino and connectivity has been double checked, the Arduino is connected to a computer and the following sketch can be compiled and uploaded.

The sketch starts with reference to a library. This library is supplied with the Arduino IDE, so don’t worry about starting a search on the internet to download it.

Pins ’11’ and 12′ refer here to the RS and RS-enable functions while 5,4,3 and 2 refer to the pins used to transfer data from the Arduino to the display. Note that you can setup data connectivity of your LCD from other pins on the Arduino, e.g. pins 8, 7, 6 and 5, but in all cases you have to declare these pins explicitly in the ‘LiquidCrystal lcd (…) statement.

This instruction tells the software that the connected lcd display is a 16×2 type. If your lcd is a 20×4 type, then the proper instruction is ‘lcd.begin (20, 4);’

And then the loop is announced. However, since in this basic sketch only one text is displayed once and forever in the ‘setup’ section there is no need to add instructions to the ‘loop’ section:

When the contrast potentiometer is turned to maximum contrast it can easily be seen that the characters are embedded in rectangle like structures. In a 16×2 lcd display there are two lines. Each consists of 16 of these rectangles. Each rectangle is formed by a matrix of 8 pixels high and 5 pixels wide. Each of the 40 individual pixels in a rectangle can be set ‘ON’ or ‘OFF’. Usually they are in ‘OFF ‘ position, that is: they have he same intensity as the background. Any letter, number or special character consists of a special configuration of ‘ON’ and ‘OFF’ pixels in their 8×5 matrix. In the HDM44780 chip 255 pre-programmed characters are available by default. This set of characters is called the lcd’s ‘ASCII character set’.

The following sketch, ‘ascii_lcd_character_set.ino’ displays on the lcd display in a loop the following data. On the first line comes the decimal (ascii) value of the character while on the second line of the display the character itself appears.

One of the funny things with the character set is that there is room for creating your own favorite character, icon or emoji. The Arduino has memory space to hold eight custom characters. Creating your own character works as follows.

Figure 4: Creating your own custom character in the 5×8 lcd pixel matrix of a lcd display ‘character’ rectangle. Here we create a ‘smiley’ and a ‘weepy’. In the byte matrix a ‘1’ means ‘pixel ON’ while a ‘0’ means ‘pixel OFF’.

Each character is built up of five bytes. Each bit corresponds with one pixel of the character, and as a bit can be ‘0’ or ‘1’, whether or not a pixel is displayed, is defined by how the byte has been set.

While we have defined the 8×5 pixel matrix of each custom character an additional instruction named ‘lcd.createChar’, is required before we can print the custom character to the lcd. Up to 8 custom characters are allowed:

Note on the uint8_t: In the official reference section on the Arduino forum (https://www.arduino.cc/en/Reference/LiquidCrystalCreateChar) the instruction says ‘lcd.write(byte(0)’. The Arduino IDE compiler needs to know however that this byte is of the unsigned 8-bit type: an uint8_t.

The loop of the sketch is quite straightforward: we print the ‘smile’ character to the first position of the lcd display, leave it in place for one second and then replace it with the ‘weep’ character. As these instructions are in the loop section the program will run forever.

It is interesting to create a custom character for the superscript ‘degree’ character when we are going to display temperatures in the next section of this paper.

This is a small, cheap and accurate sensor that records temperatures between -55 and 125 oC (-67°F to +257°F). Such a range is perfect for most applications. The accuracy in the working range (-10 to +85 oC) is 0.5 oC. One big advantage is that the DS18B20 is a one-wire device: for communication with an Arduino only one pin on the microcontroller board is necessary. Multiple DS18B20s can be connected with the Arduino via the same communication wire because each DS18B20 has a unique 8-bit identification tag. Calling this tag produces the response only of the sensor with that tag while other, identical sensors wired through the same line do not respond. A so-called pull-up resistor with a value of 4.7 kΩ between the data wire and 5V is necessary to maintain a stable signal (see wiring diagram in figure 6). If this resistor is absent, the sensor may not be recognized by the Arduino or readings may be unreliable.

The sketch, named ‘single_DS18B20_lcd_display.ino’ uses three libraries: the built-in LiquidCrystal.h and the external OneWire.h and DallasTemperature.h. The external libraries are available in the public domain (https://www.arduinolibraries.info/libraries/one-wire).

The OneWire library needs to know with which Arduino pin the sensor is expected to communicate. In our example the sensor’s data pin is connected to Arduino pin 9. In the example we soft define this pin (as a variable). In case we might need another pin we only have to change here the pin number and not worry whether the pin number must be changed elsewhere in the sketch.

The setup part takes care of identifying the sensor to the Arduino, it creates the special character ‘superscipt-degree’, sets up the lcd and instructs the lcd display to display (print) the so-called ‘permanent’ characters that is the characters that will be seen on the display al the time. In the ‘loop’ section only the variable data (temperature readouts) need to be sent to the lcd display. This is efficient, improves the speed and avoids flickering of the display. We also have Serial Monitor at hand in case trouble shooting is necessary.

Subroutines: These are calculations or procedures that are repeatedly necessary in the sketch. These tasks can be placed outside the loop and called from within the loop. Often, subroutines deal with a specific task, here control of the dynamic part of getting and displaying sensor data on the lcd display Apart from preventing chaos and therefore supporting higher efficiency the strategy of using subroutines is particularly helpful for debugging. Once a subroutine works the programmer can focus on the main job of the sketch or on other subroutines.

In this paper we have connected a 16×2 lcd ‘classic’ display to an Arduino, discussed the sketch necessary to bring the display to life, attached a DS18B20 temperature sensor to the Arduino and, finally, display sensor data using a custom character.

This classic way of connecting a lcd display to an Arduino uses 6 pins on the Arduino. With a simple application such as a one-wire temperature sensor this is not a major problem. However when an application uses more pins, or when multiple sensors must be connected with the Arduino a ‘shortage’ of pins may threaten the project. In that case an I2C lcd-display might help because the I2C protocol needs only the analog pins A4 and A5 of the Arduino. 16×2 and 20×4 lcd displays with backpack I2C extenders working with I2C are currently available while these extenders can be bought also separately. However, there is a price, that is extra use of memory. The sketch ‘single_DS18B20_lcd_display’ uses 9,106 bytes of program memory and 487 bytes of dynamic memory to run with a 16×2 lcd display. The same sketch compiled for the same but now I2C expander-supported 16×2 lcd display, gobbles up 10,928 bytes of program memory and 720 bytes of dynamic memory. The advantage of I2C is less wires and less required pins at the expense of a higher memory load.

This is a tutorial of an open source Arduino library, which lets you turn your Arduino to a “Clock”, with a Maxim Integrated DS3232 Real Time Clock module. I will show you how to install the library to Arduino IDE and make an example project with the library, throughout this tutorial while giving information digital clocks and their working principle.

A digital clock is a clock consisting of a power supply, a circuit consisting of an crystal oscillator and a display to show the time, which shows the time digitally unlike traditional analog clocks. First digital clock is made by an Austrian engineer named Josef Pallweber using a jump hour mechanism. Digital clocks have the same fundamental working principle as the analog clocks. They need a source of power to run the clock, which is the power supply, a battery or AC power, a display which can be a LED, LCD display or a seven segment display, and a time base that keeps track of the time which is the time circuit consisting of an crystal oscillator and a counter. The crystal oscillator creates a steady 60 or 50 Hertz signal. Then created signal is divided down using a counter circuit in order to create a binary number. Then this number is converted to the time format desired (12 hour or 24 hour format) and sent to the display. Digital clocks are used in nearly everywhere in our lives, such as ovens, cars, phones, televisions, computers, radios, industrial timers.

I"ll show you step by step how to use the DS3232RTC Arduino library with a simple example. In this example project, we will make a real time digital clock with an Arduino microcontroller, and a Maxim Integrated DS3232 or DS3231 Real-Time Clock module. In order to make a real time digital clock with an Arduino, first we’ll have to get the time from the real time clock module. Then we need to print the time in certain intervals to the serial monitor screen. Connections for DS3232 real time clock module to Arduino is shown below.

3. First we need to add the setup commands. In the void setup() function, add the code that starts serial communication in 9600 baud rate. Then type the library function to get the time from the RTC module. Add an if statement afterwards, which will trigger if the Arduino cannot sync up with the real time clock module and prints the situation to serial monitor. Add an else statement and make it print that the system time is set.

4. After setup is done, we need to create a function that returns the time and prints the time to serial monitor. Name the void returning function “displayTime”. Add the codes below which prints the time to serial monitor.

In this tutorial I’ve shown how to install “DS3232RTC” Arduino library, written by GitHub user “JChristensen” to Arduino IDE, showing how to use the library functions with an example, while giving information about what digital clocks are and their working principle.

In this Arduino touch screen tutorial we will learn how to use TFT LCD Touch Screen with Arduino. You can watch the following video or read the written tutorial below.

As an example I am using a 3.2” TFT Touch Screen in a combination with a TFT LCD Arduino Mega Shield. We need a shield because the TFT Touch screen works at 3.3V and the Arduino Mega outputs are 5 V. For the first example I have the HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor, then for the second example an RGB LED with three resistors and a push button for the game example. Also I had to make a custom made pin header like this, by soldering pin headers and bend on of them so I could insert them in between the Arduino Board and the TFT Shield.

So now I will explain how we can make the home screen of the program. With the setBackColor() function we need to set the background color of the text, black one in our case. Then we need to set the color to white, set the big font and using the print() function, we will print the string “Arduino TFT Tutorial” at the center of the screen and 10 pixels down the Y – Axis of the screen. Next we will set the color to red and draw the red line below the text. After that we need to set the color back to white, and print the two other strings, “by HowToMechatronics.com” using the small font and “Select Example” using the big font.

In order the code to work and compile you will have to include an addition “.c” file in the same directory with the Arduino sketch. This file is for the third game example and it’s a bitmap of the bird. For more details how this part of the code work you can check my particular tutorial. Here you can download that file:

Along 3 years I have been trying several leg mechanism, at first I decided to do a simple desing with tibial motor where placed on femur joint.This design had several problems, like it wasn"t very robust and the most importat is that having the motor (with big mass) that far from the rotating axis, caused that in some movements it generate unwanted dynamics to the robot body, making controlability worse.New version have both motors of femur/tibial limb at coxa frame, this ends with a very simple setup and at the same time, the heaviest masses of the mechanism are centered to the rotating axis of coxa limb, so even though the leg do fast movements, inertias won"t be strong enough to affect the hole robot mass, achieving more agility.Inverse Kinematics of the mechanismAfter building it I notice that this mechanism was very special for another reason, at the domain the leg normally moves, it acts as a diferential mecanism, this means that torque is almost all the time shared between both motor of the longer limbs. That was an improvent since with the old mechanism tibial motor had to hold most of the weight and it was more forced than the one for femur.To visualize this, for the same movement, we can see how tibial motor must travel more arc of angel that the one on the new version.In order to solve this mechanism, just some trigonometry is needed. Combining both cosine and sine laws, we can obtain desired angle (the one between femur and tibia) with respect to the angle the motor must achieve.Observing these equations, with can notice that this angle (the one between femur and tibia) depends on both servos angles, which means both motors are contributing to the movement of the tibia.Calibration of servosAnother useful thing to do if we want to control servo precisely is to print a calibration tool for our set up. As shown in the image below, in order to know where real angles are located, angle protactor is placer just in the origin of the rotating joint, and choosing 2 know angles we can match PWM signal to the real angles we want to manipulate simply doing a lineal relation between angles and PWM pulse length.Then a simple program in the serial console can be wrtten to let the user move the motor to the desired angle. This way the calibration process is only about placing motor at certain position and everything is done and we won"t need to manually introduce random values that can be a very tedious task.With this I have achieved very good calibrations on motors, which cause the robot to be very simetrial making the hole system more predictable. Also the calibration procedure now is very easy to do, as all calculations are done automatically. Check Section 1 for the example code for calibration.More about this can be seen in the video below, where all the building process is shown as well as the new leg in action.SECTION 1:In the example code below, you can see how calibration protocol works, it is just a function called calibrationSecuence() which do all the work until calibration is finished. So you only need to call it one time to enter calibration loop, for example by sending a "c" character thought the serial console.Also some useful function are used, like moving motor directly with analogWrite functions which all the calculations involved, this is a good point since no interrupts are used.This code also have the feature to calibrate the potentiometer coming from each motor.#define MAX_PULSE 2500 #define MIN_PULSE 560 /*---------------SERVO PIN DEFINITION------------------------*/ int m1 = 6;//FR int m2 = 5; int m3 = 4; int m4 = 28;//FL int m5 = 29; int m6 = 36; int m7 = 3;//BR int m8 = 2; int m9 = 1; int m10 = 7;//BL int m11 = 24; int m12 = 25; int m13 = 0;//BODY /*----------------- CALIBRATION PARAMETERS OF EACH SERVO -----------------*/ double lowLim[13] = {50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 50, 30, 30, 70}; double highLim[13] = {130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 130, 150, 150, 110}; double a[13] = { -1.08333, -1.06667, -1.07778, //FR -1.03333, 0.97778, 1.01111, //FL 1.03333, 1.05556, 1.07778, //BR 1.07500, -1.07778, -1.00000, //BL 1.06250 }; double b[13] = {179.0, 192.0, 194.5, //FR 193.0, 5.5, -7.5, //FL 7.0, -17.0, -16.0, //BR -13.5, 191.5, 157.0, //BL -0.875 }; double ae[13] = {0.20292, 0.20317, 0.19904 , 0.21256, -0.22492, -0.21321, -0.21047, -0.20355, -0.20095, -0.20265, 0.19904, 0.20337, -0.20226 }; double be[13] = { -18.59717, -5.70512, -2.51697, -5.75856, 197.29411, 202.72169, 185.96931, 204.11902, 199.38663, 197.89534, -5.33768, -32.23424, 187.48058 }; /*--------Corresponding angles you want to meassure at in your system-----------*/ double x1[13] = {120, 135, 90, 60, 135 , 90, 120, 135, 90, 60, 135, 90, 110}; //this will be the first angle you will meassure double x2[13] = {60, 90, 135, 120, 90, 135, 60, 90, 135, 120, 90, 135, 70};//this will be the second angle you will meassure for calibration /*--------You can define a motor tag for each servo--------*/ String motorTag[13] = {"FR coxa", "FR femur", "FR tibia", "FL coxa", "FL femur", "FL tibia", "BR coxa", "BR femur", "BR tibia", "BL coxa", "BL femur", "BL tibia", "Body angle" }; double ang1[13] = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}; double ang2[13] = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0}; float xi[500]; float yi[500]; float fineAngle; float fineL; float fineH; int motorPin; int motor = 0; float calibrationAngle; float res = 1.0; float ares = 0.5; float bres = 1.0; float cres = 4.0; float rawAngle; float orawAngle; char cm; char answer; bool interp = false; bool question = true; bool swing = false; int i; double eang; int freq = 100; // PWM frecuency can be choosen here. void connectServos() { analogWriteFrequency(m1, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m1, LOW); pinMode(m1, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m2, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m2, LOW); pinMode(m2, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m3, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m3, LOW); pinMode(m3, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m4, freq); //FL coxa digitalWrite(m4, LOW); pinMode(m4, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m5, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m5, LOW); pinMode(m5, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m6, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m6, LOW); pinMode(m6, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m7, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m7, LOW); pinMode(m7, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m8, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m8, LOW); pinMode(m8, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m9, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m9, LOW); pinMode(m9, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m10, freq); //FR coxa digitalWrite(m10, LOW); pinMode(m10, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m11, freq); //femur digitalWrite(m11, LOW); pinMode(m11, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m12, freq); //tibia digitalWrite(m12, LOW); pinMode(m12, OUTPUT); analogWriteFrequency(m13, freq); //body digitalWrite(m13, LOW); pinMode(m13, OUTPUT); } void servoWrite(int pin , double angle) { float T = 1000000.0f / freq; float usec = float(MAX_PULSE - MIN_PULSE) * (angle / 180.0) + (float)MIN_PULSE; uint32_t duty = int(usec / T * 4096.0f); analogWrite(pin , duty); } double checkLimits(double angle , double lowLim , double highLim) { if ( angle >= highLim ) { angle = highLim; } if ( angle <= lowLim ) { angle = lowLim; } return angle; } int motorInfo(int i) { enc1 , enc2 , enc3 , enc4 , enc5 , enc6 , enc7 , enc8 , enc9 , enc10 , enc11 , enc12 , enc13 = readEncoders(); if (i == 0) { rawAngle = enc1; motorPin = m1; } else if (i == 1) { rawAngle = enc2; motorPin = m2; } else if (i == 2) { rawAngle = enc3; motorPin = m3; } else if (i == 3) { rawAngle = enc4; motorPin = m4; } else if (i == 4) { rawAngle = enc5; motorPin = m5; } else if (i == 5) { rawAngle = enc6; motorPin = m6; } else if (i == 6) { rawAngle = enc7; motorPin = m7; } else if (i == 7) { rawAngle = enc8; motorPin = m8; } else if (i == 8) { rawAngle = enc9; motorPin = m9; } else if (i == 9) { rawAngle = enc10; motorPin = m10; } else if (i == 10) { rawAngle = enc11; motorPin = m11; } else if (i == 11) { rawAngle = enc12; motorPin = m12; } else if (i == 12) { rawAngle = enc13; motorPin = m13; } return rawAngle , motorPin; } void moveServos(double angleBody , struct vector anglesServoFR , struct vector anglesServoFL , struct vector anglesServoBR , struct vector anglesServoBL) { //FR anglesServoFR.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.tetta , lowLim[0] , highLim[0]); fineAngle = a[0] * anglesServoFR.tetta + b[0]; servoWrite(m1 , fineAngle); anglesServoFR.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.alpha , lowLim[1] , highLim[1]); fineAngle = a[1] * anglesServoFR.alpha + b[1]; servoWrite(m2 , fineAngle); anglesServoFR.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoFR.gamma , lowLim[2] , highLim[2]); fineAngle = a[2] * anglesServoFR.gamma + b[2]; servoWrite(m3 , fineAngle); //FL anglesServoFL.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.tetta , lowLim[3] , highLim[3]); fineAngle = a[3] * anglesServoFL.tetta + b[3]; servoWrite(m4 , fineAngle); anglesServoFL.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.alpha , lowLim[4] , highLim[4]); fineAngle = a[4] * anglesServoFL.alpha + b[4]; servoWrite(m5 , fineAngle); anglesServoFL.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoFL.gamma , lowLim[5] , highLim[5]); fineAngle = a[5] * anglesServoFL.gamma + b[5]; servoWrite(m6 , fineAngle); //BR anglesServoBR.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.tetta , lowLim[6] , highLim[6]); fineAngle = a[6] * anglesServoBR.tetta + b[6]; servoWrite(m7 , fineAngle); anglesServoBR.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.alpha , lowLim[7] , highLim[7]); fineAngle = a[7] * anglesServoBR.alpha + b[7]; servoWrite(m8 , fineAngle); anglesServoBR.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoBR.gamma , lowLim[8] , highLim[8]); fineAngle = a[8] * anglesServoBR.gamma + b[8]; servoWrite(m9 , fineAngle); //BL anglesServoBL.tetta = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.tetta , lowLim[9] , highLim[9]); fineAngle = a[9] * anglesServoBL.tetta + b[9]; servoWrite(m10 , fineAngle); anglesServoBL.alpha = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.alpha , lowLim[10] , highLim[10]); fineAngle = a[10] * anglesServoBL.alpha + b[10]; servoWrite(m11 , fineAngle); anglesServoBL.gamma = checkLimits(anglesServoBL.gamma , lowLim[11] , highLim[11]); fineAngle = a[11] * anglesServoBL.gamma + b[11]; servoWrite(m12 , fineAngle); //BODY angleBody = checkLimits(angleBody , lowLim[12] , highLim[12]); fineAngle = a[12] * angleBody + b[12]; servoWrite(m13 , fineAngle); } double readEncoderAngles() { enc1 , enc2 , enc3 , enc4 , enc5 , enc6 , enc7 , enc8 , enc9 , enc10 , enc11 , enc12 , enc13 = readEncoders(); eang1 = ae[0] * enc1 + be[0]; eang2 = ae[1] * enc2 + be[1]; eang3 = ae[2] * enc3 + be[2]; eang4 = ae[3] * enc4 + be[3]; eang5 = ae[4] * enc5 + be[4]; eang6 = ae[5] * enc6 + be[5]; eang7 = ae[6] * enc7 + be[6]; eang8 = ae[7] * enc8 + be[7]; eang9 = ae[8] * enc9 + be[8]; eang10 = ae[9] * enc10 + be[9]; eang11 = ae[10] * enc11 + be[10]; eang12 = ae[11] * enc12 + be[11]; eang13 = ae[12] * enc13 + be[12]; return eang1 , eang2 , eang3 , eang4 , eang5 , eang6 , eang7 , eang8 , eang9 , eang10 , eang11 , eang12 , eang13; } void calibrationSecuence( ) { //set servos at their middle position at firstt for (int i = 0; i <= 12; i++) { rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(i); servoWrite(motorPin , 90); } // sensorOffset0 = calibrateContacts(); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("_________________________________SERVO CALIBRATION ROUTINE_________________________________"); Serial.println("___________________________________________________________________________________________"); Serial.println("(*) Don"t send several caracter at the same time."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("Keyboard: "x"-> EXIT CALIBRATION. "c"-> ENTER CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "i"-> PRINT INFORMATION. "); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "n"-> CHANGE MOTOR (+). "b" -> CHANGE MOTOR (-)."); Serial.println(" "m"-> START CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "q"-> STOP CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "r"-> CHANGE RESOLUTION."); Serial.println(" "p"-> ADD ANGLE. "o"-> SUBTRACT ANGLE. "); Serial.println(" "s"-> SAVE ANGLE."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); while (CAL == true) { if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "x") { Serial.println("Closing CALIBRATION program..."); CAL = false; secuence = false; startDisplay(PAGE); angleBody = 90; anglesIKFR.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKFR.alpha = -45.0; anglesIKFR.gamma = 90.0; anglesIKFL.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKFL.alpha = -45.0; anglesIKFL.gamma = 90.0; anglesIKBR.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKBR.alpha = 45.0; anglesIKBR.gamma = -90.0; anglesIKBL.tetta = 0.0; anglesIKBL.alpha = 45.0; anglesIKBL.gamma = -90.0; } else if (cm == "i") { // + Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println("(*) Don"t send several caracter at the same time."); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("Keyboard: "x"-> EXIT CALIBRATION. "c"-> ENTER CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "i"-> PRINT INFORMATION. "); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "n"-> CHANGE MOTOR (+). "b" -> CHANGE MOTOR (-)."); Serial.println(" "m"-> START CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "q"-> STOP CALIBRATION."); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println(" "r"-> CHANGE RESOLUTION."); Serial.println(" "p"-> ADD ANGLE. "o"-> SUBTRACT ANGLE. "s"-> SAVE ANGLE."); Serial.println(" "); delay(500); Serial.println(" "); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); Serial.println(" "); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); Serial.println("Actual parameters of the motor: "); Serial.print("High limit: "); Serial.print(highLim[motor]); Serial.print(" Low limit: "); Serial.print(lowLim[motor]); Serial.print(" Angle 1: "); Serial.print(ang1[motor]); Serial.print(" Angle 2: "); Serial.println(ang2[motor]); Serial.println("---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"); } else if (cm == "m") { // + secuence = true; } else if (cm == "s") { // + } else if (cm == "n") { // + motor++; if (motor >= 13) { motor = 0; } Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); } else if (cm == "b") { // + motor--; if (motor < 0) { motor = 13 - 1; } Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } } if (secuence == true) { Serial.print("Starting secuence for motor: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); for (int i = 0; i <= 30; i++) { delay(20); Serial.print("."); } Serial.println("."); while (question == true) { unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 100000) { previousMicros = currentMicros; if (Serial.available() > 0) { answer = Serial.read(); if (answer == "y") { question = false; interp = true; secuence = true; } else if (answer == "n") { question = false; interp = false; secuence = true; } else { Serial.println("Please, select Yes(y) or No(n)."); } } } } answer = "t"; question = true; if (interp == false) { Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" | Place motor at 1ts position and save angle"); Serial.println(" | This position can be the higher one"); rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); calibrationAngle = 90; //start calibration at aproximate middle position of the servo. while (secuence == true) { /* find first calibration angle */ if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "p") { // + Serial.print(" | +"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle + res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "o") { // - Serial.print(" | -"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle - res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else if (cm == "q") { // quit secuence secuence = false; Serial.println(" | Calibration interrupted!!"); } else if (cm == "s") { // save angle ang1[motor] = calibrationAngle; secuence = false; Serial.print(" | Angle saved at "); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } } } if (cm == "q") { Serial.println(" |"); } else { secuence = true; Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" | Place motor at 2nd position and save angle"); Serial.println(" | This position can be the lower one"); } while (secuence == true) { /* find second calibration angle */ if (Serial.available() > 0) { cm = Serial.read(); if (cm == "p") { // + Serial.print(" | +"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle + res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "o") { // - Serial.print(" | -"); Serial.print(res); Serial.print(" : "); calibrationAngle = calibrationAngle - res; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } else if (cm == "r") { // + if (res == ares) { res = bres; } else if (res == bres) { res = cres; } else if (res == cres) { res = ares; } Serial.print("SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else if (cm == "q") { // quit secuence secuence = false; Serial.println(" | Calibration interrupted!!"); } else if (cm == "s") { // save angle ang2[motor] = calibrationAngle; secuence = false; Serial.print(" | Angle saved at "); Serial.println(calibrationAngle); } } } /*--------------------start calibration calculations------------------*/ if (cm == "q") { Serial.println("___|"); Serial.println("Calibration finished unespected."); Serial.println(" Select another motor."); Serial.print("SELECTED MOTOR: "); Serial.print(motorTag[motor]); Serial.print(". SELECTED RESOLUTION: "); Serial.println(res); } else { Serial.println("___"); Serial.println(" |___"); Serial.print( " | | Interpolating for motor: "); Serial.println(motorTag[motor]); secuence = true; //real angle is calculated interpolating both angles to a linear relation. a[motor] = (ang2[motor] - ang1[motor]) / (x2[motor] - x1[motor]); b[motor] = ang1[motor] - x1[motor] * (ang2[motor] - ang1[motor]) / (x2[motor] - x1[motor]); Serial.println(" | |"); } interp = true; } /*---------------------------make swing movement to interpolate motor encoder-----*/ if (interp == true and secuence == true) { delay(200); double x; int k = 0; int stp = 180; swing = true; i = 0; orawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); previousMicros = 0; while (swing == true) { // FIRST unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 10000) { // save the last time you blinked the LED previousMicros = currentMicros; x = x2[motor]; calibrationAngle = a[motor] * x + b[motor]; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); if ((i % 3) == 0) { yi[k+1] = x; xi[k] = rawAngle; Serial.print(" | | Real ang: "); Serial.print(x); Serial.print(" -> Servo ang: "); Serial.print(calibrationAngle); Serial.print(" Enc: "); Serial.println(rawAngle); k++; } if (i >= stp) { swing = false; } i++; } } swing = true; i = 0; while (swing == true) { // moving unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 10000) { // save the last time you blinked the LED previousMicros = currentMicros; x = x2[motor] + float(i) * (x1[motor] - x2[motor]) / stp; calibrationAngle = a[motor] * x + b[motor]; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); if ((i % 6) == 0) { yi[k+1] = x; xi[k] = rawAngle; Serial.print(" | | Real ang: "); Serial.print(x); Serial.print(" -> Servo ang: "); Serial.print(calibrationAngle); Serial.print(" Enc: "); Serial.println(rawAngle); k++; } if (i >= stp) { swing = false; } i++; } } swing = true; i = 0; while (swing == true) { // SECOND unsigned long currentMicros = micros(); if (currentMicros - previousMicros >= 10000) { // save the last time you blinked the LED previousMicros = currentMicros; x = x1[motor]; calibrationAngle = a[motor] * x + b[motor]; servoWrite(motorPin , calibrationAngle); rawAngle , motorPin = motorInfo(motor); if ((i % 3) == 0) { yi[k+1] =

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey