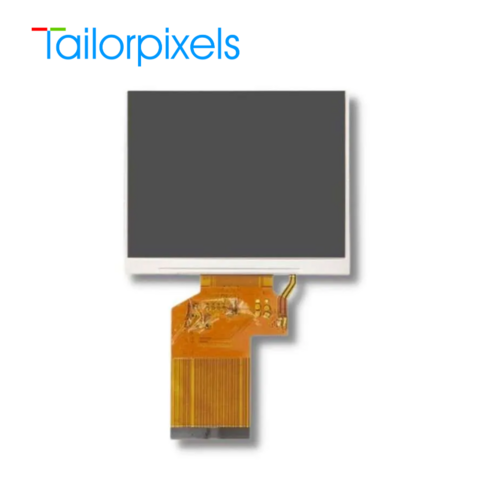

tn film tft lcd quotation

IPS (In-Plane Switching) lcd is still a type of TFT LCD, IPS TFT is also called SFT LCD (supper fine tft ),different to regular tft in TN (Twisted Nematic) mode, theIPS LCD liquid crystal elements inside the tft lcd cell, they are arrayed in plane inside the lcd cell when power off, so the light can not transmit it via theIPS lcdwhen power off, When power on, the liquid crystal elements inside the IPS tft would switch in a small angle, then the light would go through the IPS lcd display, then the display on since light go through the IPS display, the switching angle is related to the input power, the switch angle is related to the input power value of IPS LCD, the more switch angle, the more light would transmit the IPS LCD, we call it negative display mode.

The regular tft lcd, it is a-si TN (Twisted Nematic) tft lcd, its liquid crystal elements are arrayed in vertical type, the light could transmit the regularTFT LCDwhen power off. When power on, the liquid crystal twist in some angle, then it block the light transmit the tft lcd, then make the display elements display on by this way, the liquid crystal twist angle is also related to the input power, the more twist angle, the more light would be blocked by the tft lcd, it is tft lcd working mode.

A TFT lcd display is vivid and colorful than a common monochrome lcd display. TFT refreshes more quickly response than a monochrome LCD display and shows motion more smoothly. TFT displays use more electricity in driving than monochrome LCD screens, so they not only cost more in the first place, but they are also more expensive to drive tft lcd screen.The two most common types of TFT LCDs are IPS and TN displays.

A thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD) is a variant of a liquid-crystal display that uses thin-film-transistor technologyactive matrix LCD, in contrast to passive matrix LCDs or simple, direct-driven (i.e. with segments directly connected to electronics outside the LCD) LCDs with a few segments.

In February 1957, John Wallmark of RCA filed a patent for a thin film MOSFET. Paul K. Weimer, also of RCA implemented Wallmark"s ideas and developed the thin-film transistor (TFT) in 1962, a type of MOSFET distinct from the standard bulk MOSFET. It was made with thin films of cadmium selenide and cadmium sulfide. The idea of a TFT-based liquid-crystal display (LCD) was conceived by Bernard Lechner of RCA Laboratories in 1968. In 1971, Lechner, F. J. Marlowe, E. O. Nester and J. Tults demonstrated a 2-by-18 matrix display driven by a hybrid circuit using the dynamic scattering mode of LCDs.T. Peter Brody, J. A. Asars and G. D. Dixon at Westinghouse Research Laboratories developed a CdSe (cadmium selenide) TFT, which they used to demonstrate the first CdSe thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD).active-matrix liquid-crystal display (AM LCD) using CdSe TFTs in 1974, and then Brody coined the term "active matrix" in 1975.high-resolution and high-quality electronic visual display devices use TFT-based active matrix displays.

The circuit layout process of a TFT-LCD is very similar to that of semiconductor products. However, rather than fabricating the transistors from silicon, that is formed into a crystalline silicon wafer, they are made from a thin film of amorphous silicon that is deposited on a glass panel. The silicon layer for TFT-LCDs is typically deposited using the PECVD process.

Polycrystalline silicon is sometimes used in displays requiring higher TFT performance. Examples include small high-resolution displays such as those found in projectors or viewfinders. Amorphous silicon-based TFTs are by far the most common, due to their lower production cost, whereas polycrystalline silicon TFTs are more costly and much more difficult to produce.

The twisted nematic display is one of the oldest and frequently cheapest kind of LCD display technologies available. TN displays benefit from fast pixel response times and less smearing than other LCD display technology, but suffer from poor color reproduction and limited viewing angles, especially in the vertical direction. Colors will shift, potentially to the point of completely inverting, when viewed at an angle that is not perpendicular to the display. Modern, high end consumer products have developed methods to overcome the technology"s shortcomings, such as RTC (Response Time Compensation / Overdrive) technologies. Modern TN displays can look significantly better than older TN displays from decades earlier, but overall TN has inferior viewing angles and poor color in comparison to other technology.

Most TN panels can represent colors using only six bits per RGB channel, or 18 bit in total, and are unable to display the 16.7 million color shades (24-bit truecolor) that are available using 24-bit color. Instead, these panels display interpolated 24-bit color using a dithering method that combines adjacent pixels to simulate the desired shade. They can also use a form of temporal dithering called Frame Rate Control (FRC), which cycles between different shades with each new frame to simulate an intermediate shade. Such 18 bit panels with dithering are sometimes advertised as having "16.2 million colors". These color simulation methods are noticeable to many people and highly bothersome to some.gamut (often referred to as a percentage of the NTSC 1953 color gamut) are also due to backlighting technology. It is not uncommon for older displays to range from 10% to 26% of the NTSC color gamut, whereas other kind of displays, utilizing more complicated CCFL or LED phosphor formulations or RGB LED backlights, may extend past 100% of the NTSC color gamut, a difference quite perceivable by the human eye.

The transmittance of a pixel of an LCD panel typically does not change linearly with the applied voltage,sRGB standard for computer monitors requires a specific nonlinear dependence of the amount of emitted light as a function of the RGB value.

In-plane switching was developed by Hitachi Ltd. in 1996 to improve on the poor viewing angle and the poor color reproduction of TN panels at that time.

It achieved pixel response which was fast for its time, wide viewing angles, and high contrast at the cost of brightness and color reproduction.Response Time Compensation) technologies.

Less expensive PVA panels often use dithering and FRC, whereas super-PVA (S-PVA) panels all use at least 8 bits per color component and do not use color simulation methods.BRAVIA LCD TVs offer 10-bit and xvYCC color support, for example, the Bravia X4500 series. S-PVA also offers fast response times using modern RTC technologies.

A technology developed by Samsung is Super PLS, which bears similarities to IPS panels, has wider viewing angles, better image quality, increased brightness, and lower production costs. PLS technology debuted in the PC display market with the release of the Samsung S27A850 and S24A850 monitors in September 2011.

TFT dual-transistor pixel or cell technology is a reflective-display technology for use in very-low-power-consumption applications such as electronic shelf labels (ESL), digital watches, or metering. DTP involves adding a secondary transistor gate in the single TFT cell to maintain the display of a pixel during a period of 1s without loss of image or without degrading the TFT transistors over time. By slowing the refresh rate of the standard frequency from 60 Hz to 1 Hz, DTP claims to increase the power efficiency by multiple orders of magnitude.

Due to the very high cost of building TFT factories, there are few major OEM panel vendors for large display panels. The glass panel suppliers are as follows:

External consumer display devices like a TFT LCD feature one or more analog VGA, DVI, HDMI, or DisplayPort interface, with many featuring a selection of these interfaces. Inside external display devices there is a controller board that will convert the video signal using color mapping and image scaling usually employing the discrete cosine transform (DCT) in order to convert any video source like CVBS, VGA, DVI, HDMI, etc. into digital RGB at the native resolution of the display panel. In a laptop the graphics chip will directly produce a signal suitable for connection to the built-in TFT display. A control mechanism for the backlight is usually included on the same controller board.

The low level interface of STN, DSTN, or TFT display panels use either single ended TTL 5 V signal for older displays or TTL 3.3 V for slightly newer displays that transmits the pixel clock, horizontal sync, vertical sync, digital red, digital green, digital blue in parallel. Some models (for example the AT070TN92) also feature input/display enable, horizontal scan direction and vertical scan direction signals.

New and large (>15") TFT displays often use LVDS signaling that transmits the same contents as the parallel interface (Hsync, Vsync, RGB) but will put control and RGB bits into a number of serial transmission lines synchronized to a clock whose rate is equal to the pixel rate. LVDS transmits seven bits per clock per data line, with six bits being data and one bit used to signal if the other six bits need to be inverted in order to maintain DC balance. Low-cost TFT displays often have three data lines and therefore only directly support 18 bits per pixel. Upscale displays have four or five data lines to support 24 bits per pixel (truecolor) or 30 bits per pixel respectively. Panel manufacturers are slowly replacing LVDS with Internal DisplayPort and Embedded DisplayPort, which allow sixfold reduction of the number of differential pairs.

Kawamoto, H. (2012). "The Inventors of TFT Active-Matrix LCD Receive the 2011 IEEE Nishizawa Medal". Journal of Display Technology. 8 (1): 3–4. Bibcode:2012JDisT...8....3K. doi:10.1109/JDT.2011.2177740. ISSN 1551-319X.

K. H. Lee; H. Y. Kim; K. H. Park; S. J. Jang; I. C. Park & J. Y. Lee (June 2006). "A Novel Outdoor Readability of Portable TFT-LCD with AFFS Technology". SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers. AIP. 37 (1): 1079–82. doi:10.1889/1.2433159. S2CID 129569963.

2.2. THE WEBSITE MAY COLLECT USERS" INFORMATION WHEN THE USER REGISTERS WITH, BROWSES, ACCESSES SERVICES PROVIDED BY, OR PARTICIPATES IN AD OR PROMOTIONAL CAMPAIGN INITIATED BY THE WEBSITE. THE WEBSITE MAY ALSO OBTAIN THE SAME PERSONAL INFORMATION FROM ITS BUSINESS PARTNERS.

2.4. THE WEBSITE COLLECTS TRANSACTION DATA BETWEEN YOU AND TRENDFORCE AND FROM RELEVANT BUSINESS PARTNERS. THESE INCLUDE SPECIFIC PRODUCTS AND SERVICES THAT ARE DIRECTLY OBTAINED FROM THE WEBSITE.

TFT displays are full color LCDs providing bright, vivid colors with the ability to show quick animations, complex graphics, and custom fonts with different touchscreen options. Available in industry standard sizes and resolutions. These displays come as standard, premium MVA, sunlight readable, or IPS display types with a variety of interface options including HDMI, SPI and LVDS. Our line of TFT modules include a custom PCB that support HDMI interface, audio support or HMI solutions with on-board FTDI Embedded Video Engine (EVE2).

A TN or Twisted Nematic TFT LCD is a cost-effective high performance LCD. It offers good brightness performance and fast response times. However, it suffers in one key area and that is its viewing cone. TN LCD’s typically have three good viewing angle directions. In these directions the image is typically clear and colors are consistent up to 80 degrees from the center of the LCD. The remaining viewing direction is usually good through 40-50 degrees from center. Afterwards, the image is likely to invert, almost appearing like an x-ray.

TFT LCD, acronym for Thin Film Transistor Liquid Crystal Display, is a technology developed for improve image quality and has countless consumer and industrial uses.

Specifically, within TFT monitors, liquid crystals allow faster and smoother state transitions while saving power, resulting in high image quality on the display, which appears without flickering or bright irregularities (unlike simpler LCD screens).

TFT screens can be of different sizes, ranging from small 3.5" screens to large displays, and can also be identified by their area of use or by certain special features and applications, such as multitouch.

TFT displays are always clearly visible in sunlight, making them particularly suitable for outdoor use. This type of display is also particularly light, thin and energy-efficient, as well as being relatively inexpensive in relation to the technical features offered.

Digimax has an extensive catalogue ofTFT screens from 7" to 23", LCD displays and professional monitors capable of handling a high number of pixels to enable high image quality, high resolution and a screen without glare or flicker.

TFT technology is now a consolidated reality for the choice of monitors, screens and industrial displays: following this market evolution, Digimax offers the latest generation of TFT touch screen solutions, multi touch monitors and transparent displays able to offer the right option for every need.

We offer both standard and customised TFT LCDs through strategic partnerships with leading international suppliers and brands: Ampire displays, Raystar monitors and DLC screens, as well as RockTech, RockTouch and AUO touch screens.

Together with Digimax consultancy, a specific service is also available to configure TFT kits consisting of a TFT LCD monitor and matching PC board: it is possible to customise CPU and coverlens, touch technology used and connection wiring between motherboard and display.

LCD stands for “Liquid Crystal Display” and TFT stands for “Thin Film Transistor”. These two terms are used commonly in the industry but refer to the same technology and are really interchangeable when talking about certain technology screens. The TFT terminology is often used more when describing desktop displays, whereas LCD is more commonly used when describing TV sets. Don’t be confused by the different names as ultimately they are one and the same. You may also see reference to “LED displays” but the term is used incorrectly in many cases. The LED name refers only to the backlight technology used, which ultimately still sits behind an liquid crystal panel (LCD/TFT).

As TFT screens are measured differently to older CRT monitors, the quoted screen size is actually the full viewable size of the screen. This is measured diagonally from corner to corner. TFT displays are available in a wide range of sizes and aspect ratios now. More information about the common sizes of TFT screens available can be seen in our section about resolution.

The aspect ratio of a TFT describes the ratio of the image in terms of its size. The aspect ratio can be determined by considering the ratio between horizontal and vertical resolution.

The resolution of a TFT is an important thing to consider. All TFT’s have a certain number of pixels making up their liquid crystal matrix, and so each TFT has a “native resolution” which matches this number. It is always advisable to run the TFT at its native resolution as this is what it is designed to run at and the image does not need to be stretched or interpolated across the pixels. This helps keep the image at its most clear and at optimum sharpness. Some screens are better than others at running below the native resolution and interpolating the image which can sometimes be useful in games.

You generally cannot run a TFT at a resolution of above its native resolution although some screens have started to offer “Virtual” resolutions, for example “virtual 4k” where the screen will accept a 3840 x 2160 input from your graphics card but scale it back to match the native resolution of the panel which is often 2560 x 1440 in these examples. This whole process is rather pointless though as you lose a massive amount of image quality in doing so.

Unlike on CRT’s where the dot pitch is related to the sharpness of the image, the pixel pitch of a TFT is related to the distance between pixels. This value is fixed and is determined by the size of the screen and the native resolution (number of pixels) offered by the panel. Pixel pitch is normally listed in the manufacturers specification. Generally you need to consider that the ‘tighter’ the pixel pitch, the smaller the text will be, and potentially the sharper the image will be. To be honest, monitors are normally produced with a sensible resolution for their size and so even the largest pixel pitches return a sharp images and a reasonable text size. Some people do still prefer the larger-resolution-crammed-into-smaller-screen option though, giving a smaller pixel pitch and smaller text. It’s down to choice and ultimately eye-sight.

While this aspect is not always discussed by display manufacturers it is a very important area to consider when selecting a TFT monitor. The LCD panels producing the image are manufactured by many different panel vendors and most importantly, the technology of those panels varies. Different panel technologies will offer different performance characteristics which you need to be aware of. Their implementation is dependent on the panel size mostly as they vary in production costs and in target markets. The four main types of panel technology used in the desktop monitor market are:

TN Film was the first panel technology to be widely used in the desktop monitor market and is still regularly implemented in screens of all sizes thanks to its comparatively low production costs. TN Film is generally characterized by good pixel responsiveness making it a popular choice for gamer-orientated screens. Where overdrive technologies are also applied the responsiveness is improved further. TN Film panels are also available supporting 120Hz+ refresh rates making them a popular choice for stereoscopic 3D compatible screens. While older TN Film panels were criticized for their poor black depth and contrast ratios, modern panels are actually very good in this regard, often producing a static contrast ratio of up to 1000:1. Perhaps the main limitation with TN Film technology is its restrictive viewing angles, particularly in the vertical field. While specs on paper might look promising, in reality the viewing angles are restrictive and there are noticeable contrast and gamma shifts as you change your line of sight. TN Film panels are normally based around a 6-bit colour depth as well, with a Frame Rate Control (FRC) stage added to boost the colour palette. They are often excluded from higher end screens or by colour enthusiasts due to this lower colour depth and for their viewing angle limitations. TN Film panels are regularly used in general lower end and office screens due to cost, and are very popular in gaming screens thanks to their low response times and high refresh rate support. Pretty much all of the main panel manufacturers produce TN Film panels and all are widely used (and often interchanged) by the screen manufacturers.

IPS was originally introduced to try and improve on some of the drawbacks of TN Film. While initially viewing angles were improved, the panel technology was traditionally fairly poor when it came to response times and contrast ratios. Production costs were eventually reduced and the main investor in this technology has been LG.Display (formerly LG.Philips). The original IPS panels were developed into the so-called Super IPS (S-IPS) generation and started to be more widely used in mainstream displays. These were characterized by their good colour reproduction qualities, 8-bit colour depth (without the need for Frame Rate Control) and very wide viewing angles. These panels were traditionally still quite slow when it came to pixel response times however and contrast ratios were mediocre. In more recent years a change was made to the pixel alignment in these IPS panels (see our detailed panel technology article for more information) which gave rise to the so-called Horizontal-IPS (H-IPS) classification. With the introduction of overdrive technologies, response times were improved significantly, finally making IPS a viable choice for gaming. This has resulted more recently in IPS panels being often regarded as the best all-round technology and a popular choice for display manufacturers in today’s market. Improvements in energy consumption and reduced production costs lead to the generation of so-called e-IPS panels. Unlike normal 8-bit S-IPS and H-IPS classification panels, the e-IPS generation worked with a 6-bit + FRC colour depth. Developments and improvements with colour depths also gave rise to a generation of “10-bit” panels with some manufacturers inventing new names for the panels they were using, including the co-called Performance-IPS (p-IPS). It is important to understand that these different variants are ultimately very similar and the names are often interchanged by different display vendors. For more information, see our detailed panel technologies guide.

Nowadays IPS panels are produced and developed by several leading panel manufacturers. LG.Display technically own the IPS name and continue to invest in this popular technology. Samsung began production of their very similar PLS (Plane to Line Switching) technology, as did AU Optronics with their AHVA (Advanced Hyper Viewing Angle). These are all so similar in performance and features that they can be simply referred to now as “IPS-type”. Indeed monitor manufacturers will normally stick to the common IPS name but the underlying panel may be produced by any number of different manufacturers investing in this type of panel tech. AU Optronics have done a good job with finally increasing the refresh rate of their IPS panels, and making them a more viable option for gamers. Native 144Hz IPS-type panels are now available and response times continue to be reduced as well. Modern IPS panels are characterized by decent response times, if not quite as fast as TN Film they are certainly more fluid than older panels. Contrast ratios are typically around 1000:1 and viewing angles continue to be the widest and most stable of any panel technology. You will find varying colour depths including 6-bit+FRC and 8-bit commonly being used, although this makes little difference in practice. One of the remaining limitations with IPS-type technologies are the so-called “IPS glow”, where darker content introduces a pale glow when viewed from an angle. It’s a characteristic of the panel technology and pretty hard to avoid without additional filters being added to the panels. On larger and wider screens some people find this glow distracting and problematic.

The original early VA panels were quickly scrapped due to their poor viewing angles, and in their place came the two main types of VA matrix. Multi-Domain Vertical Alignment (MVA) and Patterned Vertical Alignment (PVA) panels. These VA variants were characterized by their reasonably wide viewing angles, being better than TN Film but not as wide as IPS. They were originally poor when it came to pixel response times but offered 8-bit colour depths and the best static contrast ratios of all the technologies discussed here. Traditionally VA panels were capable of static contrast ratios of around 1000 – 1200:1 but this has even been improved now to 3000:1 and above. Until very recently VA panels remained very slow and so were not really suitable for gaming. However during 2012 we saw advancements with the latest generation of VA panels and through the use of overdrive technologies this has been significantly improved. Perhaps the main limitation with VA panels is still their viewing angles when compared with popular IPS panel options. Gamma and contrast shifts can be an issue and the technology also suffers from an inherent off-centre contrast shift issue which can be distracting to some users. Through the years we have seen several different generations of VA panels. AU Optronics are the main manufacturer of MVA matrices, and we have seen the so-called Premium-MVA (P-MVA) and Advanced-MVA (AMVA) generations emerge. Chi Mei Innolux (previously Chi Mei Optoelectronics / CMO) also make their own variant of MVA which they call Super-MVA (S-MVA).The only manufacturer of PVA panels is Samsung as it is their own version of VA technology. We have seen several generations from them including Super-PVA (S-PVA) and cPVAandSVA. For more information, see our detailed panel technologies guide.

This technology was developed by Sharp for use in some of their TFT displays. It consists of several improvements that Sharp claim to have made, mainly to counter the drawbacks of the popular TN Film technology. They have introduced an Anti-Glare / Anti-Reflection (AGAR) screen coating which forms a quarter-wavelength filter. Incident light is reflected back from front and rear surfaces 180° out of phase, thus canceling reflection rather diffusing it as others do. As well as reducing glare and reflection from the screen, this is marketed as being able to offer deeper black levels. Sharp also claim to offer better contrast ratios than any competing technology (VA and IPS); but with more emphasis on improving these other technologies, this is probably not the case with more modern panels. There are very few ASV monitors around really, with the majority of the market being dominated by TN, VA and IPS panels.

This technology was developed by BOE Hydis, and is not really very widely used in the desktop TFT market, more in the mobile and tablet sectors. It is worth mentioning however in case you come across displays using this technology. It was developed by BOE Hydis to offer improved brightness and viewing angles to their display panels and claims to be able to offer a full 180/180 viewing angle field as well as improved colours. This is basically just an advancements from IPS and is still based on In Plane technology. They claim to “modify pixels” to improve response times and viewing angles thanks to improved alignment. They have also optimised the use of the electrode surface (fringe field effect), removed shadowed areas between pixels, horizontally aligned electric fields and replaced metal electrodes with transparent ones. More information about AFFS can be found here.

This panel technology was developed by NEC LCD, and is reported to offer wide viewing angles, fast response times, high luminance, wide colour gamut and high definition resolutions. Of course, there is a lot of marketing speak in there, and the technology is not widely employed in the mainstream monitor market. Wide viewing angles are possible thanks to the horizontal alignment of liquid crystals when electrically charged. This alignment also helps keep response times low, particularly in grey to grey transitions. Their SFT range also offers high definition resolutions and are commonly used in medical displays where extra fine detail is required.

NEC’s SFT technology was first developed to be labelled as Advanced-SFT (A-SFT) which offered enhanced luminance figures. This then developed further to Super Advanced-SFT (SA-SFT) where colour gamut reached 72% of the NTSC colour space, and then to Ultra Advanced-SFT (UA-SFT) where the gamut was still at 72% or higher, but with a further enhancement of the luminance as compared with SA-SFT. These changes were all made possible thanks to the improved transmissivity of the SFT technology. More information is available from NEC LCD

Take for instance this example response time graph (rise times from 0 > x) I have put together. The X-axis defines the grey scale ranging from code 0 to code 255, and the Y-axis shows the response time across this range. As you progress to the right of the graph, the transitions are getting progressively lighter. So for instance at code 100 the transition is from black > dark grey, but at code 200 the transition is from black > light grey. At code 255, this is the change from black > white and is traditionally the fastest transition. It is the fastest because this is the widest change and therefore the largest voltage is applied to the liquid crystals. For many years, manufacturers have quoted the fastest transition of the panel as the figure for ‘response time’. This was always at the black > white > black transition and so this became accepted as the ISO standard norm for measuring response time. If this graph were a real panel, it would very likely be quoted as a 10ms screen and shows a characteristic curve for a traditional, non-overdriven, TN Film panel.

One thing to note regarding pixel response time is that the overall performance of the TFT will also depend on the technology of the panel used. TN film panels offer response time graphs similar to that above, but screens based on traditional VA / IPSvariant panels can show response time graphs more like this (we are assuming for now non-overdriven panels):

This is again a mock up, but shows a typical curve shape you may expect from a VA / IPS panel (not using overdrive) when compared with TN film. Although a VA/IPS screen might be quoted as perhaps 12ms for instance, this might not mean it is as reactive as a 12ms TN film panel. Again, it is a good idea to check for reviews which measure the response time across the whole range as well as to consider real-life responsiveness tests such as those we carry out in our reviews.

Overdrive or ‘Response Time Compensation’ (RTC) is a technology which is designed to boost the response times of pixels across all transitions, with particular focus on improving the grey to grey changes which is the most important as those transitions are far more common in real-life uses. It is achieved by sending an over-voltage to the pixels to make them change orientation more quickly. While the full black > white change remains largely unchanged (since it already received the maximum voltage anyway), improvements across other transitions are often dramatic. With the introduction of overdriven panels the ISO point is not always the fastest transition any more, and so if a monitor has a response time quoted as “grey to grey / G2G” then you can be pretty certain it is using overdrive technology. The manufacturers still want to quote the fastest response time of their panel and show the improvements they have made though, but be wary of this change away from the ISO standard of quoting response times. The ISO response times have hit a wall really with TN Film stuck at 5 – 8ms, IPS stuck at around 16ms and MVA/PVA stuck at about 12ms. However, with the introduction of overdrive technologies, the more important grey to grey transitions are now significantly improved, and response times of 1 – 5ms G2G are now common place. These technologies have allow significant improvements in all panel technologies, but particularly in IPS and VA panels where response times were previously poor.

Some reviews sites including TFTCentral have access to advanced photosensor (photodiodе + low-noise operational amplifier) and oscilloscope measurement equipment which allows them to measure response time as detailed above. See our article about response times for more information on that method. Graphs showing response time according to their equipment are produced. Other sites rely on observed responsiveness to compare how well a panel can perform in practice and what a user might see in normal use. We think it is important to study both methods if possible to give a fuller picture of a panels performance. For visual tests TFTCentral uses a program called PixPerAn (developed by Prad.de) which is good for comparing monitor responsiveness with its series of tests. The favourite seems to be the moving car test as shown here:

In addition to pixel response time measurements and visual tests described above, it is also possible to capture the levels of blurring and smearing the human eye will experience on a display. This is achieved using a pursuit camera setup. They are simply cameras which follow the on-screen motion and are extremely accurate at measuring motion blur, ghosting and overdrive artefacts of moving images. Since they simulate the eye tracking motion of moving eyes, they can be useful in giving an idea of how a moving image appears to the end user. It is the blurring caused by eye tracking on continuously-displayed refreshes (sample-and-hold) that we are keen to analyse with this new approach. This is not pixel persistence caused by response times; but a different cause of display motion blur which cannot be captured using static camera tests. Low response times do have a positive impact on motion blur, and higher refresh rates also help reduce blurring to a degree. It does not matter how low response times are, or how high refresh rates are, you will still see motion blur from LCD displays under normal operation to some extent and that is what this section is designed to measure. Further technologies specifically designed to reduce perceived motion blur are required to eliminate the blur seen on these type of sample-and-hold displays which we will also look at.

These tests capture the kind of blurring you would see with the naked eye when tracking moving objects across the screen (example from the Asus ROG Swift PG279Q). As you increase the refresh rate the perceived blurring is reduced, as refresh rate has a direct impact on motion blur. It is not eliminated entirely due to the nature of the sample-and-hold LCD display and the tracking of your eyes. No matter how fast the refresh rate and pixel response times are, you cannot eliminate the perceived motion blur without other methods.Tests like the above would give you an idea of the kind of perceived motion blur range when using the particular screen without any bur reduction mode active.

The Contrast Ratio of a TFT is the difference between the darkest black and the brightest white it is able to display. This is really defined by the pixel structure and how effectively it can let light through and block light out from the backlight unit. As a rule of thumb, the higher the contrast ratio, the better. The depth of blacks and the brightness of the whites are better with a higher contrast ratio. This is also referred to as the static contrast ratio.

When considering a TFT monitor, a contrast ratio of 1000:1 is pretty standard nowadays for TN Film and IPS-type panels. VA-type panels can offer static contrast ratios of 3000:1 and above which are significantly higher than other competing panel technologies.

Some technologies boast the ability to dynamically control contrast (Dynamic Contrast Ratio – DCR) and offer much higher contrast ratios which are incredibly high (millions:1 for instance!). Be wary of these specs as they are dynamic only, and the technology is not always very useful in practice. Traditionally, TFT monitors were said to offer poor black depth, but with the extended use of VA panels, the improvements from IPS and TN Film technology, and new Dynamic Contrast Control technologies, we are seeing good improvements in this area. Black point is also tied in to contrast ratio. The lower the black point, the better, as this will ensure detail is not lost in dark image when trying to distinguish between different shades.

Brightness as a specification is a measure of the brightest white the TFT can display, and is more accurately referred to as its luminance. Typically TFT’s are far too bright for comfortable use, and the On Screen Display (OSD) is used to turn the brightness setting down. Brightness is measure in cd/m2 (candella per metre squared). Note that the recommended brightness setting for a TFT screen in normal lighting conditions is 120 cd/m2. Default brightness of screens out of the box is regularly much higher so you need to consider whether the monitor controls afford you a decent adjustment range and the ability to reduce the luminance to a comfortable level based on your ambient lighting conditions. Different uses may require different brightness settings as well so it is handy when reviews record the luminance range possible from the screen as you adjust the brightness control from 100 to 0%.

The colour depth of a TFT panel is related to how many colours it can produce and should not be confused with colour space (gamut). The more colours available, the better the colour range can potentially be. Colour reproduction is also different however as this related to how reliably produced the colours are compared with those desired.

At the lower end, TN Film panels are normally quite economical, and their sub pixels only have 64 possible orientations each, giving rise to a true colour depth of only 262,144 (i.e. 64 steps on each RGB = 64 x 64 x 64 = 18). This is also referred to commonly s 18-bit colour (i.e. 6 bits per RGB sub pixel = 6 + 6 + 6) This colour depth is pretty limited and so in order to reach 16 million colours and above, panel manufacturers commonly use two technologies: Dithering and Frame Rate Control (FRC). These terms are often interchanged, but strictly can mean different things. These technologies simulate other colours allowing the colour depth to improve to typically 16.2 million colours.

Spatial Dithering – The dithering method involves assigning appropriate colour values from the available colour palette to close-by pixels in such a way that it gives the impression of a new colour tone which otherwise could not have been created at all. In doing so, there complex mappings according to which the ground colours are mutually assigned, otherwise it could result in colour noise / dithering noise. Dithering can be used to allow 6-Bit panels, like TN Film, to show 16.2 million perceived colours. This can however sometimes be detectable to the user, and can result in chessboard like patterns being visible in some cases.

Frame Rate Control / Temporal Dithering– The other method is Frame-Rate-Control (FRC), also referred to sometimes as temporal dithering. This works by combining four colour frames as a sequence in time, resulting in perceived mixture. In basic terms, it involves flashing between two colour tones rapidly to give the impression of a third tone, not normally available in the palette. This allows a total of 16.2 reproducible million colours. Thanks to Frame-Rate-Control, TN panel monitors have come pretty close to matching the colours and image quality of VA or IPS panel technology, but there are a number of FRC algorithms which vary in their effectiveness. Sometimes, a twinkling artefact can be seen, particularly in darker shades, which is a side affect of such technologies. Some TN Film panels are now quoted as being 16.7 million colours, and this is down to new processes allowing these panels to offer a better colour depth compared with older TN panels.

Colour gamut in TFT monitors refers to the range of colours the screen is capable of displaying, and how much of a given reference colour space it might be able to display. It is ultimately linked to backlight technology and not to the panel itself.

Laser Displays are capable of producing the biggest colour gamut for a system with three basic colours, but even a laser display cannot reproduce all the colours the human eye can see, although it is quite close to doing that. However, in today’s monitors, both CRT and LCD (except for some models I’ll discuss below), the spectrum of each of the basic colours is far from monochromatic. In the terms of the CIE diagram it means that the vertexes of the triangle are shifted from the border of the diagram towards its centre.

Traditionally, LCD monitors were capable of giving approximate coverage of the sRGB reference colour space as shown in the diagram above. This is defined by the backlighting used in these displays – Cold-cathode fluorescent lamps (CCFL) that are employed which emit radiation in the ultraviolet range which is transformed into white colour with the phosphors on the lamp’s walls. These backlight lamps shine through the LCD panel, and through the RGB sub-pixels which act as filters for each of the colours. Each filter cuts a portion of spectrum, corresponding to its pass-band, out of the lamp’s light. This portion must be as narrow as possible to achieve the largest colour gamut.

LED backlighting has now become the norm for desktop monitors and is available in a few variations. The most common is White-LED (W-LED), which is a replacement for standard CCFL backlighting. The LED’s are placed in a line along the edge of the matrix, and the uniform brightness of the screen is ensured by a special design of the diffuser. The colour gamut is limited to sRGB as standard (around 68 – 72% NTSC) but the units are cheaper to manufacturer and so are being utilised in more and more screens, even in the more budget range. They do have their environmental benefits as they can be recycled, and they have a thinner profile making them popular in super-slim range models and notebook PC’s. It is possible to extend the colour gamut of W-LED displays using “Quantum Dot” technologies which are fairly new.

Viewing angles are quoted in horizontal and vertical fields and often look like this in listed specifications: 170/160 (170° in horizontal viewing field, 160° in vertical). The angles are related to how the image looks as you move away from the central point of view, as it can become darker or lighter, and colours can become distorted as you move away from your central field of view. Because of the pixel orientation, the screen may not be viewable as clearly when looking at the screen from an angle, but viewing angles of TFT’s vary depending on the panel technology used.

As a general rule, the viewing angles are IPS-type > VA-type > TN Film. The viewing angles are often over exaggerated in manufacturers specs, especially with TN Film panels where quoted specs of 160 / 160 and even 170 / 170 are based on overly loose measuring techniques. Be wary of 176/176 figures as these are sometimes used as over-exaggerated specs for a TN Film panel and are based on more lapse measurement techniques as well.

TFT screens do not refresh in the same way as a CRT screen does, where the image is redrawn at a certain rate. As a TFT is a static image, and each pixel refreshes independently, setting the TFT at a common 60Hz native refresh rate does not cause the same problems as it would on a CRT. There is no cathode ray gun redrawing the image as a whole on a TFT. You will not get flicker, which is the main reason for having a high refresh rate on a CRT in the first place. Standard TFT monitors operate with a 60Hz recommended refresh rate, but can sometimes support up to 75Hz maximum (within the spec) or sometimes even further using ‘overclocking’ methods. The reason that 60Hz is recommended by all the manufacturers is that it is related to the vertical frequency that TFT panels run at. Some more detailed data sheets for the panels themselves clearly show that the operating vertical frequency is between about 56 and 64Hz, and that the panels ‘typically’ run at 60Hz (see the LG.Philips LM230W02 datasheet for instance – page 11). If you decide to run your refresh rate from your graphics card above the recommended 60Hz it will work fine, but the interface chip on the monitor will be in charge of scaling the frequency down to 60Hz anyway. Some screens will allow you to run at the maximum 75Hz as well for an additional boost in frame rates and some minor improvements in motion clarity. The support of this will really depend on the screen, your graphics card and the video connection being used. You may find the screen operates fine at the higher refresh rate setting but in reality the screen will often drop frames to meet the 60Hz recommended setting (or spec of the panel) anyway. Generally we would suggest sticking to 60Hz on standard TFT monitors.

The desire to offer higher frame rate support and higher refresh rates has lead to panel manufacturers developing panels which can natively support 120Hz+. It is common now to see 120Hz or 144Hz as natively supported refresh rates. This allows much higher frame rates to be displayed and the increase in refresh rate also brings about positive improvements in perceived motion clarity. TN Film panels have been around for many years now with high refresh rates and in recent years there has been development in IPS-type and VA-type panels to boost their refresh rates as well. You will also now see some ‘overclocked’ monitors available where manufacturers have attempted to boost the refresh rate further. For instance the native 144Hz IPS-type panel of the Asus ROG Swift PG279Q up to 165Hz, or the 144Hz native VA-type panel of the Acer Predator Z35 up to 200Hz. Results of these overclocks do vary and are not guaranteed but may provide some additional benefits.

You will see more mention of higher refresh rates from both LCD televisions and now desktop monitors. It’s important to understand the different technologies being used though and what constitutes a ‘real’ 120Hz and what is ‘interpolated’:

Interpolated 120Hz+– These technologies are the ones commonly used in LCD TV’s where TV signal input is limited to 50 / 60 Hz anyway (depending on PAL vs NTSC). To help overcome the issues relating to motion blur on such sets, manufacturers began to introduce a technology to artificially boost the frame rate of the screen. This is done by an internal processing within the hardware which adds an intermediate and interpolated (guessed / calculated) frame between each real frame, boosting from 50 / 60fps to 100 / 120 fps. This technology can offer a noticeable improvement in practice when it is controlled very well. Some sets even have 240 and 480Hz technologies which operate in the same way, but with further interpolation and inserted frames. See here for further information.

Manufacturer specifications will usually list power consumption levels for the monitor which tell you the typical power usage you can expect from their model. This can help give you an idea of running costs, carbon footprint and electricity demands which are particularly important when you’re talking about multiple monitors or a large office environment. Power consumption of an LCD monitor is typically impacted by 3 areas:

Specs will often list a typical usage for the screen, normally related to whatever the default factory brightness control / luminance is. They may also list a maximum usage, when brightness is turned up to full and sometimes also an additional maximum when USB ports are in use. A standby power usage is often also included indicating the power draw when the screen is in standby mode. Some screens also feature various presets or modes designed to help limit power consumption, often just involving preset brightness settings. Again these can be useful in multi-monitor environments.

This relates to the connection type from the TFT to your PC or other external device. Older screens nearly all came with an analogue connection, commonly referred to as D-sub or VGA. This allows a connection from the VGA port on your graphics card, where the signal being produced from the graphics card is converted from a pure digital to an analogue signal. There are a number of algorithms implemented in TFT’s which have varying effectiveness in improving the image quality over a VGA connection. Some TFT’s with then offer a DVI input as well to allow you to make use of the DVI output from your graphics card which you might have. This will allow a pure digital connection which can sometimes offer an improved image quality. It is possible to get DVI – VGA converters. These will not offer any improvements over a standard analogue connection, as you are still going through a conversion from digital to analogue somewhere along the line. Dual-Link DVI is also sometimes used which is a single DVI connection but with more pins, allowing for higher resolution/refresh rate support than a single-link DVI.

TN Film panels are the mostly widely used in the desktop display market and have been for many years since LCD monitors became mainstream. Smaller sized screens (15″, 17″ and 19″) are almost exclusively limited to this technology in fact and it has also extended into larger screen sizes over the last 7 years or so, now being a popular choice in the 20 – 28″ bracket as well. The TN Film panels are made by many different manufacturers, with the big names all having a share in the market (Samsung, LG.Display, AU Optronics) and being backed up by the other companies including most notably Innolux and Chunghwa Picture Tubes (CPT). You may see different generations of TN Film being discussed, but over the years the performance characteristics have remained similar overall.

TN Film has always been so widely used because it is comparatively cheap to produce panels based on this technology. As such, manufacturers have been able to keep costs of their displays down by using these panels. This is also the primary reason for the technology to be introduced into the larger screen sizes, where the production costs allow manufacturers to drive down retail costs for their screens and compete for new end-users.

The other main reason for using TN Film is that it is fundamentally a responsive technology in terms of pixel latency, something which has always been a key consideration for LCD buyers. It has long been the choice for gaming screens and response times have long been, and still are today, the lowest out of all the technologies overall. Response times typically reach a limit of around 5ms at the ISO quoted black > white > black transition, and as low as 1ms across grey to grey transitions where Response Time Compensation (overdrive) is used. TN Film has also been incorporated into true 120Hz+ refresh rate desktop displays, pairing low response times with high refresh rates for even better moving picture and gaming experiences, improved frame rates and adding 3D stereoscopic content support. Modern 120Hz+ refresh rate screens normally also support NVIDIA 3D Vision 2 and their LightBoost system which brings about another advantage for gaming. You can use the LightBoost strobed backlight system in 2D gaming to greatly reduce the perceived motion blur which is a significant benefit. Some screens even include a native blur reduction mode instead of having to rely on LightBoost ‘hacks’, providing better support for strobing backlights and improving gaming experiences when it comes to perceived motion blur. As a result, TN Film is still the choice for gamer screens because of the low response times and 120Hz+ refresh rate support.

The main problem with TN Film technology is that viewing angles are pretty restrictive, especially vertically, and this is evident by a characteristic severe darkening of the image if you look at the screen from below. Contrast and colour tone shifts can be evident with even a slight movement off-centre, and this is perhaps the main drawback in modern TN Film panels. Some TN Film panels are better than others and there have been improvements over the years to some degree, but they are still far more restrictive with fields of view than other panel technologies. The commonly quoted 170/160 viewing angles are an unfair indication of the actual real-life performance really, especially when you consider the vertical contrast shifts. Where viewing angles are quoted by a manufacturer as 160/160 or 170/160 that is a clear sign that the panel technology will be TN Film incidentally.

Movie playback is often hampered by ‘noise’ and artifacts, especially where overdrive is used. Black depth was traditionally quite poor on TN Film matrices due to the crystal alignment, however, in recent years, black depth has improved somewhat and is generally very good on modern screens, often surpassing IPS based screens and able to commonly reach contrast ratios of ~1000:1. TN Film is normally only a true 6-bit colour panel technology, but is able to offer a 16.7 million colour depth thanks to dithering and Frame Rate Control methods (6-bit + FRC). Some true 8-bit panels have become available in recent years (2014 onwards) but given the decent implementation of FRC on other 6-bit+FRC panels, the real-life difference is not something to concern yourself with too much.

Most TN Film panels are produced with a 1920 x 1080 resolution, although some larger sizes have become available with higher resolutions. A new generation of Quad HD 2560 x 1440 27″ TN Film panels emerged in 2014. We’ve also seen the introduction of 28″ Ultra HD 3840 x 2160 resolution TN Film panels become available, and adopted in many of the lower cost “4k” models in the market. Where used, the Anti-Glare (AG) coating used on most TN Film panels is moderately grainy – not as grainy as some older IPS panel coatings, but not as light as modern IPS, VA or equivalents. Also at the time of writing there are no ultra-wide (21:9 aspect ratio) or curved format TN Film panels in production.

MVA technology, was later developed by Fujitsu in 1998 as a compromise between TN Film and IPS technologies. On the one hand, MVA provided a full response time of 25 milliseconds (that was impossible at the time with IPS, and not easily achievable with TN), and on the other hand, MVA matrices had wide viewing angles of 160 – 170 degrees, and thus could better compete with IPS in that parameter. The viewing angles were also good in the vertical field (an area where TN panels suffer a great deal) as well as the horizontal field. MVA technology also provided high contrast ratios and good black depth, which IPS and TN Film couldn’t quite meet at the time.

As MVA developed over the years the problem became that the response times were not as good as TN film panels and was very difficult to improve. Sadly, the response time grows dramatically when there’s a smaller difference between the pixel’s initial and final states (i.e. the more common grey to grey transitions). Thus, such matrices were unsuitable for dynamic games. With the introduction of RTC and overdrive technologies, the manufacturers launched a new breed of MVA discussed in the following sections.

Premium MVA (P-MVA) panels were produced by AU Optronics, and Super MVA (S-MVA) panels by Chi Mei Optoelectronics (now Innolux) and Fujitsu from 1998 onwards. AU Optronics have since entered a more recent generation referred to as AMVA (see the next section) and S-MVA panels are rarely used in mainstream monitors nowadays. When they were launched they were able to offer improved response times across grey to grey (G2G) transitions which is a great improvement in the MVA market. While responsiveness was still not as fast as TN Film panels using similar RTC technologies, the improvement was obvious and quite drastic. This was really the first time that MVA matrices could be considered for gaming, and arrived at the time when overdrive was being more widely implemented in the market.

While some improvements have been made, the color-reproduction properties of these modern MVA technologies can still be problematic in some situations. Such panels give you vivid and bright colors, but due to the peculiarities of the domain technology many subtle color tones (dark tones often) are lost when you are looking at the screen strictly perpendicularly. When you deflect your line of sight just a little, the colors are all there again. This is a characteristic “VA panel contrast shift” (sometimes referred to as ‘black crush’ due to the loss of detail in dark colours) and some users pick up on this and might find it distracting. Thus, MVA matrices are somewhere between IPS and TN technologies as concerns color rendering and viewing angles. On the one hand, they are better than TN matrices in this respect, but on the other hand the above-described shortcoming prevents them from challenging IPS matrices, especially for colour critical work.

Traditionally MVA panels offered 8-Bit colour depth (a true 16.7 million colours) which is still common place today. We have yet to see any new breed of 10-bit capable MVA panel even using Frame Rate Control (8-bit + FRC). Black depth is a strong point of these P-MVA /S-MVA panels, being able to produce good static contrast ratios as a result of around 1000 – 1200:1 in practice. Certainly surpassing IPS matrices of the time as well as most TN Film panels. This has improved since with more recent AMVA panels to 3000 – 5000:1 (see next section).

MVA panels also offer some comparatively good movie playback with noise and artifacts quite low compared with other technologies. The application of overdrive doesn’t help in this area, but MVA panels are pretty much the only ones which haven’t suffered greatly in movie playback as a result. Many of the MVA panels are still pretty good in this area, sadly something which overdriven TN Film, IPS and PVA panels can’t offer. While CMO are still manufacturing some S-MVA matrices, AU Optronics no longer produce P-MVA panels and instead produce their newer generation of MVA, called AMVA (see below).

AU Optronics have more recently (around 2005) been working on their latest generation of MVA panel technology, termed ‘Advanced Multi Domain Vertical Alignment’ (AMVA). This is still produced today although a lot of their focus has moved to the similarly named, and not to be confused AHVA (Advanced Hyper Viewing Angle, IPS-type) technology. Compared with older MVA generations, AMVA is designed to offer improved performance including reduced colour washout, and the aim to conquer the significant problem of colour distortion with traditional wide viewing angle technology. This technology creates more domains than conventional multi-domain vertical alignment (MVA) LCD’s and reduces the variation of transmittance in oblique angles. It helps improve colour washout and provides better image quality in oblique angles than conventional VA LCD’s. Also, it has been widely recognized worldwide that AMVA technology is one of the few ways to provide optimized image quality through multiple domains.

AMVA provides an extra-high contrast ratio of greater than 1200:1, reaching 5000:1 in manufacturer specs at the time of writing for desktop monitor panels by optimized colour-resist implementation and a new pixel design and combining the panels with W-LED backlighting units. In practice the contrast ratio is typically nearer to 3000:1 from what we’ve seen, but still far beyond IPS and TN Film matrices. The result is a more comfortable viewing experience for the consumer, even on dimmer images. This is one of the main improvements with modern AMVA panels certainly, and remains way above what competing panel technologies can offer.

AMVA still has some limitations however in practice, still suffering from the off-centre contrast shift you see from VA matrices. Viewing angles are therefore not as wide as IPS technology and the technology is often dismissed for colour critical work as a result. As well as this off-centre contrast shift, the wide viewing angles often show more colour and contrast shift than competing IPS-type panels, although some recent AMVA panel generations have shown improvements here (see BenQ GW2760HS for instance with new “Color Shift-free” technology). Responsiveness is better than older MVA offerings certainly, but remains behind TN Film and IPS/PLS in practice. The Anti-Glare (AG) coating used on most panels is light, and sometimes even appears “semi glossy” and so does not produce a grainy image.

AUO developed a series of vertical-alignment (VA) technologies over the years. This is specifically for the TV market although a lot of the changes experienced through these generations applies to monitor panels as well over the years. Most recently, the company developed its AMVA5 technology not only to improve the contrast ratio, but also to enable a liquid crystal transmission improvement of 30% compared to AMVA1 in 2005. This was accomplished by effectively improving the LC disclination line using newly developed polymer-stabilized vertical-alignment (PSA) technology. PSA is a process used to improve cell transmittance, helping to improve brightness, contrast ratio and liquid crystal switching speeds.

We have included this technology in this section as it is a modern technology still produced by Sharp as opposed to the older generations of MVA discussed above. Sharp are not a major panel manufacturer in the desktop space, but during 2013 began to invest in new and interesting panels using their MVA technology. Of note is their 23.5″ sized MVA panel which was used in the Eizo Foris FG2421 display. This is the first MVA panel to offer a native 120Hz refresh rate, making it an attractive option for gamers. Response times had been boosted significantly on the most part, bringing this MVA technology in line with modern IPS-type panels when it comes to pixel latency. The 120Hz support finally allowed for improved frame rates and motion smoothness from VA technology, helping to rival the wide range of 120Hz+ TN Film panels on the market.

Of particular note also are the excellent contrast ratios of this technology, reaching up to an excellent 5000:1 in practice, not just on paper. Viewing angles are certainly better than TN Film and so overall these MVA panels can offer an attractive all-round option for gaming, without some of the draw-backs of the TN Film panels. Viewing angles are not as wide as IPS panel types and there is still some noticeable gamma shift at wider angles, and the characteristic VA off-centre contrast shift still exists.

There was the same problem with traditional PVA matrices as with MVA offerings – their response time grew considerably when there’s a smaller difference between the initial and final states of the pixel. Again, PVA panels were not nearly as responsive as TN Film panels. With the introduction of MagicSpeed (Samsung’s overdrive / RTC) with later generations (see below), response times have been greatly improved and are comparable to MVA panels in this regard on similarly spec-ed panels. They still remain behind TN Film panels in gaming use, but the overdrive really has helped improve in this area. There are no PVA panels supporting native 120Hz+ refresh rates and Samsung have no plans to produce any at this time. In fact Samsung’s investment in PVA seems to have been cut back significantly in favour of their IPS-like PLS technology.

The contrast ratio of PVA matrices is a strong point, as it is with MVA. Older PVA panels offered contrast ratios of 1000 – 1200:1 typically, but remained true to their spec in many cases. As such at the time of their main production they were better than TN Film, IPS and even MVA in this regard. Movie playback is perhaps one area which is a weak point for PVA, especially on Samsung’s overdriven panels. Noise and artifacts are common unfortunately and the panels lose out to MVA in this regard. Most PVA panels were true 8-bit modules, although some generations (see below) began to use 6-bit+FRC instead. There are no 10-bit supporting PVA panels available, either native 10-bit or 8-bit+FRC. Panel coating is generally light on PVA panels, quite similar to a lot of MVA panels.

Close up inspection of the pixels making up an S-PVA matrix reveals the above. The dual sub-pixels consist of two zones, A and B, with one being turned on only at high brightness. So, the first picture shows red sub-pixels of roughly rectangular shape while the second picture shows two small

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey