bitmap animation arduino tft lcd price

ILI9341 based TFT Touchscreen Display Shields are very popular low cost Display Shields for Arduino. Visuino has had support for them for quite a while, but I never had chance to write a Tutorial on how to use them. Recently however few people asked questions about using displays with Visuino, so I decided to make a tutorial.

In this Tutorial, I will show you how easy it is, to connect the Shield to Arduino, and program it with Visuino to animate a Bitmap to move around on the Display.

In the "Shields" dialog expand the "Displays" category, and select the "TFT Color Touch Screen Display ILI9341 Shield", then click on the "+" button to add it (Picture 2)

Next we need to add Graphics elements to render text and bitmap. First we will add graphics element to draw the shadow of the text:In the Object Inspector, click on the "..." button next to the value of the "Elements" property of the "TFT Display" Element (Picture 1)

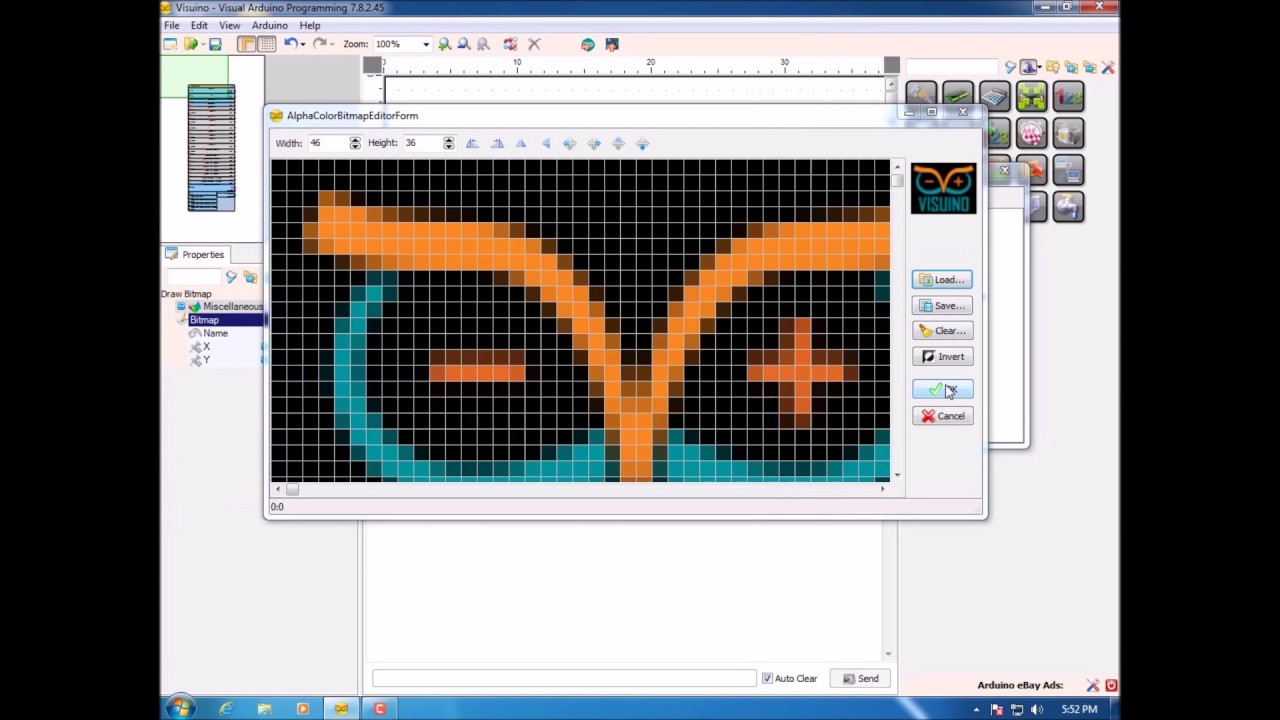

Next we will add graphics element to draw the bitmap:In the Elements editor select “Draw Bitmap”, and then click on the "+" button (Picture 1) to add one (Picture 2)

In the Object Inspector, click on the "..." button next to the value of the "Bitmap" property of the "Draw Bitmap1" Element (Picture 2) to open the "Bitmap Editor" (Picture 3)

In the File Open Dialog, select the bitmap to draw, and click on the "Open" button (Picture 4). If the file is too big it may not be able to fit in the Arduino memory. If you get out of memory error during the compilation, you may need to select a smaller bitmap

To animate the Bitmap, we need to control its X and Y position. For this we will add pins for the X and Y properties:In the Object Inspector click on the "Pin" button at front of the "X" property of the "Draw Bitmap1" element (Picture 1), and select "Integer SinkPin" (Picture 2)

In the Object Inspector click on the "Pin" button at front of the "Y" property of the "Draw Bitmap1" element (Picture 3), and select "Integer SinkPin" (Picture 4)

We will use 2 Integer sine generators to animate the bitmap movement:Type "sine" in the Filter box of the Component Toolbox then select the "Sine Integer Generator" component (Picture 1), and drop two of them it in the design area

Add TipAsk QuestionCommentDownloadStep 9: In Visuino: Configure the Second Sine Generator, and Connect the Sine Generators to the X and Y Coordinate Pins of the Bitmap

Connect the "Out" output pin of the SineIntegerGenerator1component to the "X" input pin of the "Shields.TFT Sisplay.Elements.Draw Bitmap1" element of the Arduino component (Picture 4)

Connect the "Out" output pin of the SineIntegerGenerator2component to the "Y" input pin of the "Shields.TFT Display.Elements.Draw Bitmap1" element of the Arduino component (Picture 5)

To render the bitmap every time the X and Y position are updated we need to send a clock signal to the "Draw Bitmap1" element. To send the command after the positions have been changed, we need a way to synchronize the events. For this we will use Repeat component to constantly generate events, and Clock Multi Source to generate 2 events in sequence. The first event will clock the sine generators to update the X and Y positions, and the second will clock the "Draw Bitmap1" :Type "repeat" in the Filter box of the Component Toolbox, then select the "Repeat" component (Picture 1), and drop it in the design area (Picture 2)

Connect the "Pin[ 1 ]" output pin of the "Clock" input pin of the "Shields.TFT Display.Elements.Draw Bitmap1" element of the Arduino component (Picture 6)

Pictures 2, 3, 4 and 5 and the Video show the connected and powered up project. You will see the Bitmap moving around the ILI9341 based TFT Touchscreen Display Shield as seen on the Video.

Also attached is the Visuino project, that I created for this Instructable, and the bitmap with the Visuino logo. You can download and open it in Visuino: https://www.visuino.com

Displaying a custom image or graphic on a LCD display is a very useful task as displays are now a premium way of providing feedback to users on any project. With this functionality, we can build projects that display our own logo, or display images that help users better understand a particular task the project is performing, providing an all-round improved User Experience (UX) for your Arduino or ESP8266 based project. Today’s tutorial will focus on how you can display graphics on most Arduino compatible displays.

The procedure described in this tutorial works with all color displays supported by Adafruit’s GFX library and also works for displays supported by the TFTLCD library from Adafruit with little modification. Some of the displays on which this procedure works include:

While these are the displays we have, and on which this tutorial was tested, we are confident it will work perfectly fine with most of the other Arduino compatible displays.

For each of the displays mentioned above, we have covered in past how to program and connect them to Arduino. You should check those tutorials, as they will give you the necessary background knowledge on how each of these displays works.

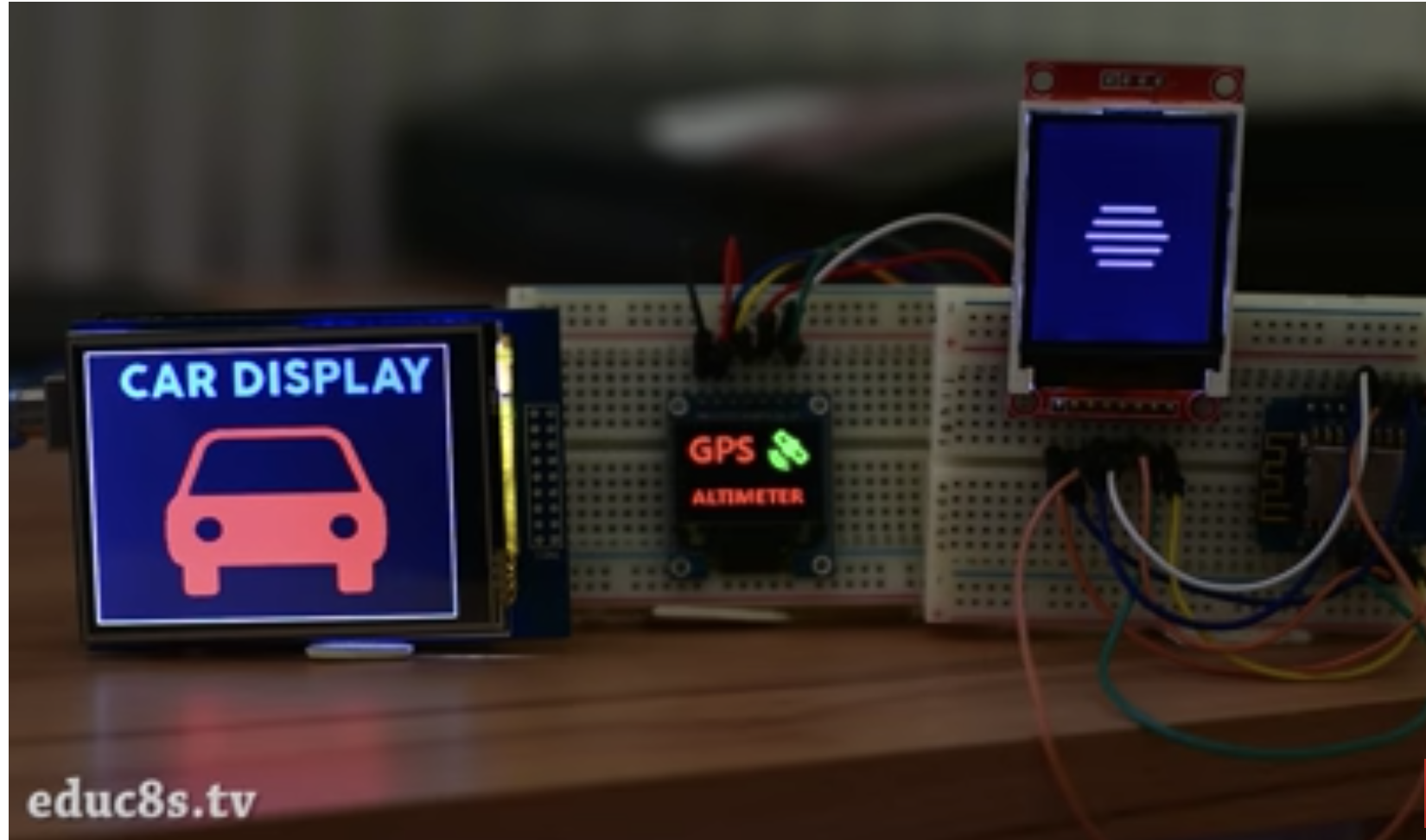

For this tutorial, we will use the 2.8″ ILI9325 TFT Display which offers a resolution of 320 x 340 pixels and we will display a bitmap image of a car.

To demonstrate how things work, we will use the 2.8″ TFT Display. The 2.8″ TFT display comes as a shield which plugs directly into the Arduino UNO as shown in the image below.

Not all Arduino displays are available as shields, so when working with any of them, connect the display as you would when displaying text (we recommend following the detailed tutorial for the display type you use of the above list). This means no special connection is required to display graphics.

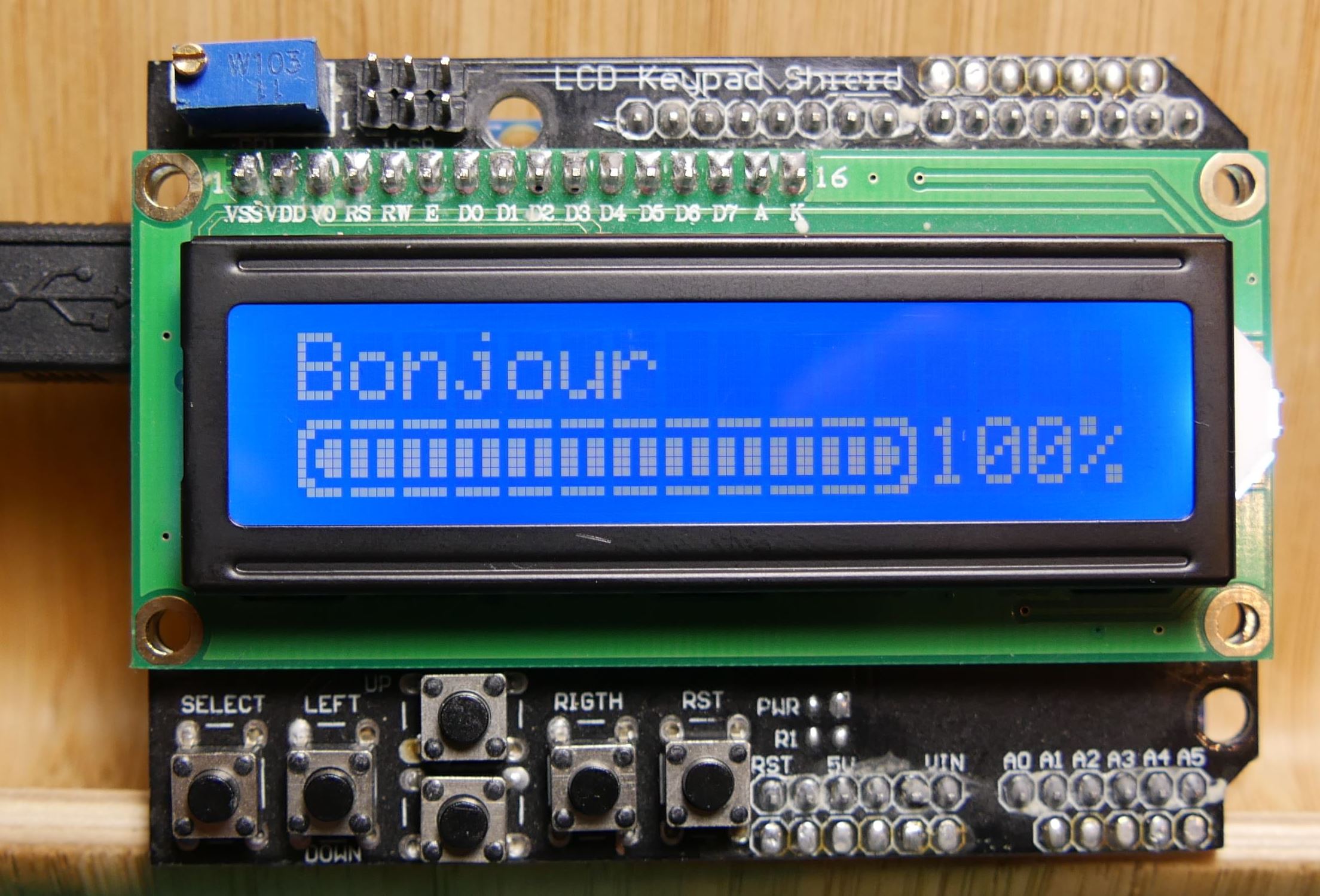

Before an image is displayed on any of the Arduino screens, it needs to be converted to a C compatible hex file and that can only happen when the image is in bitmap form. Thus, our first task is to create a bitmap version of the graphics to be displayed or convert the existing image to a bitmap file. There are several tools that can be used for creation/conversion of bitmap images including, Corel Draw and Paint.net, but for this tutorial, we will use the Paint.net.

Your graphics could also include some text. Just ensure the background is black and the fill color is white if you plan to change the color within your Arduino code.

With the graphics done, save both files as .bmp with 24bits color.It is important to keep in mind that large bitmaps use up a lot of memory and may prevent your code from running properly so always keep the bitmaps as small as possible.

Image2Code is an easy-to-use, small Java utility to convert images into a byte array that can be used as a bitmap on displays that are compatible with the Adafruit-GFX or Adafruit TFTLCD (with little modification) library.

All we have to do is to load the graphics into the software by clicking the “Choose file” button and it will automatically generate a byte array equivalent to the selected bitmap file.

Paste the bit array in the graphics.c file and save. Since we have two graphics (the car and the text), You can paste their data array in the same file. check the graphics.c file attached to the zip file, under the download section to understand how to do this. Don’t forget to declare the data type as “const unsigned char“, add PROGEM in front of it and include the avr/pgmspace.h header file as shown in the image below. This instructs the code to store the graphics data in the program memory of the Arduino.

With this done, we are now ready to write the code. Do note that this procedure is the same for all kind of displays and all kind of graphics. Convert the graphics to a bitmap file and use the Img2code utility to convert it into a hex file which can then be used in your Arduino code.

To reduce the amount of code, and stress involved in displaying the graphics, we will use two wonderful libraries; The GFX library and the TFTLCD library from Adafruit.

The GFX library, among several other useful functions, has a function called drawBitmap(), which enables the display of a monochrome bitmap image on the display. This function allows the upload of monochrome only (single color) graphics, but this can be overcome by changing the color of the bitmap using some code.

The Adafruit libraries do not support all of the displays but there are several modifications of the libraries on the internet for more displays. If you are unable to find a modified version of the library suitable for your the display, all you need do is copy the code of the drawBitmap() function from the GFX library and paste it in the Arduino sketch for your project such that it becomes a user-defined function.

The first two are thex and y coordinates of a point on the screen where we want the image to be displayed. The next argument is the array in which the bitmap is loaded in our code, in this case, it will be the name of the car and the text array located in the graphics.c file. The next two arguments are the width and height of the bitmap in pixels, in other words, the resolution of the image. The last argument is the color of the bitmap, we can use any color we like. The bitmap data must be located in program memory since Arduino has a limited amount of RAM memory available.

As usual, we start writing the sketch by including the libraries required. For this procedure, we will use the TFTLCD library alone, since we are assuming you are using a display that is not supported by the GFX library.

Next, we specify the name of the graphics to be displayed; car and title. At this stage, you should have added the bit array for these two bitmaps in the graphics.c file and the file should be placed in the same folder as the Arduino sketch.

With that done, we proceed to the void loop function, under the loop function, we call the drawbitmap() function to display the car and the text bitmap using different colors.

The last section of the code is the drawBitmap function itself, as earlier mentioned, to use the drawbitmap() function with the Adafruit TFTLCD library, we need to copy the function’s code and paste into the Arduino sketch.

Plug in your screen as shown above. If you are using any other display, connect it as shown in the corresponding linked tutorial. With the schematics in place, connect the Arduino board to your PC and upload the code. Don’t forget the graphics file needs to be in the same folder as the Arduino sketch.

That’s it for this tutorial guys. The procedure is the same for all kinds of Arduino compatible displays. If you get stuck while trying to replicate this using any other display, feel free to reach out to me via the comment sections below.

In this tutorial, I will show you how easy it is to connect the shield to the Arduino and program it using visualino to make the bitmap move on the display.

As shown in picturesTo to start programming the Arduino, insert the TFT shield into the top of the Arduino Uno, you need to install the Arduino IDE from here: Make sure to install 1. 6.

First, we will add the graphic element to draw the shadow of the text: now we will add the graphic element to draw the text: Next, we will add the graphic element to draw the bitmap: to animate the bitmap, we need to control its X and Y positions.

To do this, we will add pins for the X and Y attributes: We will animate the bitmap movement using 2 integer sine generators: to render the bitmap every time we update the X and Y positions, we need to send the clock signal to the \”draw Bitmap1\” element.

I picked up the following Adafruit TFT LCD:This lovely little display breakout is the best way to add a small, colorful, and bright display to any project. Since the display uses 4-wire SPI to communicate and has its own ...

I"ve played with the example code to do some line drawings, as well as to pull a bitmap from an attached SD card. I also figured out how to do some basic animation with the following pseudocode:

Question #2 has to do with bitmap animation. I figured out how to pull a similar 30x30 image, and I can move it around the screen, similar to the line drawing animation. However, redrawing the animation currently involves accessing the SD card at every movement, which seems slow and incorrect. I think the correct way to do it would be to pull the bitmap into an object of some kind, but I don"t know how to do this.

I am messing around with TFT displays now and have been interested in my TFT displays bitmap function, however, it is very slow. when doing any other kind of colour printing/messages it is about as instantaneous as I"d expect, but when doing bitmaps it takes almost 30seconds to fully update the 320x480px screen.

I"m wondering if this is normal for this type of display and setup and if not then, how can I speed it up! Ideally I"d like to display simple animations!

Arduino Uno: Bitmap Animation on ILI9341 TFT Touchscreen Display Shield With Visuino: ILI9341 based TFT Touchscreen Display Shields are very popular low cost Display Shields for...

Arduino Uno: Bitmap Animation on ILI9341 TFT Touchscreen Display Shield With Visuino: ILI9341 based TFT Touchscreen Display Shields are very popular low cost Display Shields for...

In this article, you will learn how to use TFT LCDs by Arduino boards. From basic commands to professional designs and technics are all explained here.

There are several components to achieve this. LEDs, 7-segments, Character and Graphic displays, and full-color TFT LCDs. The right component for your projects depends on the amount of data to be displayed, type of user interaction, and processor capacity.

TFT LCD is a variant of a liquid-crystal display (LCD) that uses thin-film-transistor (TFT) technology to improve image qualities such as addressability and contrast. A TFT LCD is an active matrix LCD, in contrast to passive matrix LCDs or simple, direct-driven LCDs with a few segments.

In Arduino-based projects, the processor frequency is low. So it is not possible to display complex, high definition images and high-speed motions. Therefore, full-color TFT LCDs can only be used to display simple data and commands.

There are several components to achieve this. LEDs, 7-segments, Character and Graphic displays, and full-color TFT LCDs. The right component for your projects depends on the amount of data to be displayed, type of user interaction, and processor capacity.

TFT LCD is a variant of a liquid-crystal display (LCD) that uses thin-film-transistor (TFT) technology to improve image qualities such as addressability and contrast. A TFT LCD is an active matrix LCD, in contrast to passive matrix LCDs or simple, direct-driven LCDs with a few segments.

In Arduino-based projects, the processor frequency is low. So it is not possible to display complex, high definition images and high-speed motions. Therefore, full-color TFT LCDs can only be used to display simple data and commands.

After choosing the right display, It’s time to choose the right controller. If you want to display characters, tests, numbers and static images and the speed of display is not important, the Atmega328 Arduino boards (such as Arduino UNO) are a proper choice. If the size of your code is big, The UNO board may not be enough. You can use Arduino Mega2560 instead. And if you want to show high resolution images and motions with high speed, you should use the ARM core Arduino boards such as Arduino DUE.

In electronics/computer hardware a display driver is usually a semiconductor integrated circuit (but may alternatively comprise a state machine made of discrete logic and other components) which provides an interface function between a microprocessor, microcontroller, ASIC or general-purpose peripheral interface and a particular type of display device, e.g. LCD, LED, OLED, ePaper, CRT, Vacuum fluorescent or Nixie.

The LCDs manufacturers use different drivers in their products. Some of them are more popular and some of them are very unknown. To run your display easily, you should use Arduino LCDs libraries and add them to your code. Otherwise running the display may be very difficult. There are many free libraries you can find on the internet but the important point about the libraries is their compatibility with the LCD’s driver. The driver of your LCD must be known by your library. In this article, we use the Adafruit GFX library and MCUFRIEND KBV library and example codes. You can download them from the following links.

You must add the library and then upload the code. If it is the first time you run an Arduino board, don’t worry. Just follow these steps:Go to www.arduino.cc/en/Main/Software and download the software of your OS. Install the IDE software as instructed.

First you should convert your image to hex code. Download the software from the following link. if you don’t want to change the settings of the software, you must invert the color of the image and make the image horizontally mirrored and rotate it 90 degrees counterclockwise. Now add it to the software and convert it. Open the exported file and copy the hex code to Arduino IDE. x and y are locations of the image. sx and sy are sizes of image. you can change the color of the image in the last input.

Upload your image and download the converted file that the UTFT libraries can process. Now copy the hex code to Arduino IDE. x and y are locations of the image. sx and sy are size of the image.

In this template, We converted a .jpg image to .c file and added to the code, wrote a string and used the fade code to display. Then we used scroll code to move the screen left. Download the .h file and add it to the folder of the Arduino sketch.

In this template, We used sin(); and cos(); functions to draw Arcs with our desired thickness and displayed number by text printing function. Then we converted an image to hex code and added them to the code and displayed the image by bitmap function. Then we used draw lines function to change the style of the image. Download the .h file and add it to the folder of the Arduino sketch.

In this template, We added a converted image to code and then used two black and white arcs to create the pointer of volumes. Download the .h file and add it to the folder of the Arduino sketch.

In this template, We added a converted image and use the arc and print function to create this gauge. Download the .h file and add it to folder of the Arduino sketch.

while (a < b) { Serial.println(a); j = 80 * (sin(PI * a / 2000)); i = 80 * (cos(PI * a / 2000)); j2 = 50 * (sin(PI * a / 2000)); i2 = 50 * (cos(PI * a / 2000)); tft.drawLine(i2 + 235, j2 + 169, i + 235, j + 169, tft.color565(0, 255, 255)); tft.fillRect(200, 153, 75, 33, 0x0000); tft.setTextSize(3); tft.setTextColor(0xffff); if ((a/20)>99)

while (b < a) { j = 80 * (sin(PI * a / 2000)); i = 80 * (cos(PI * a / 2000)); j2 = 50 * (sin(PI * a / 2000)); i2 = 50 * (cos(PI * a / 2000)); tft.drawLine(i2 + 235, j2 + 169, i + 235, j + 169, tft.color565(0, 0, 0)); tft.fillRect(200, 153, 75, 33, 0x0000); tft.setTextSize(3); tft.setTextColor(0xffff); if ((a/20)>99)

In this template, We display simple images one after each other very fast by bitmap function. So you can make your animation by this trick. Download the .h file and add it to folder of the Arduino sketch.

In this template, We just display some images by RGBbitmap and bitmap functions. Just make a code for touchscreen and use this template. Download the .h file and add it to folder of the Arduino sketch.

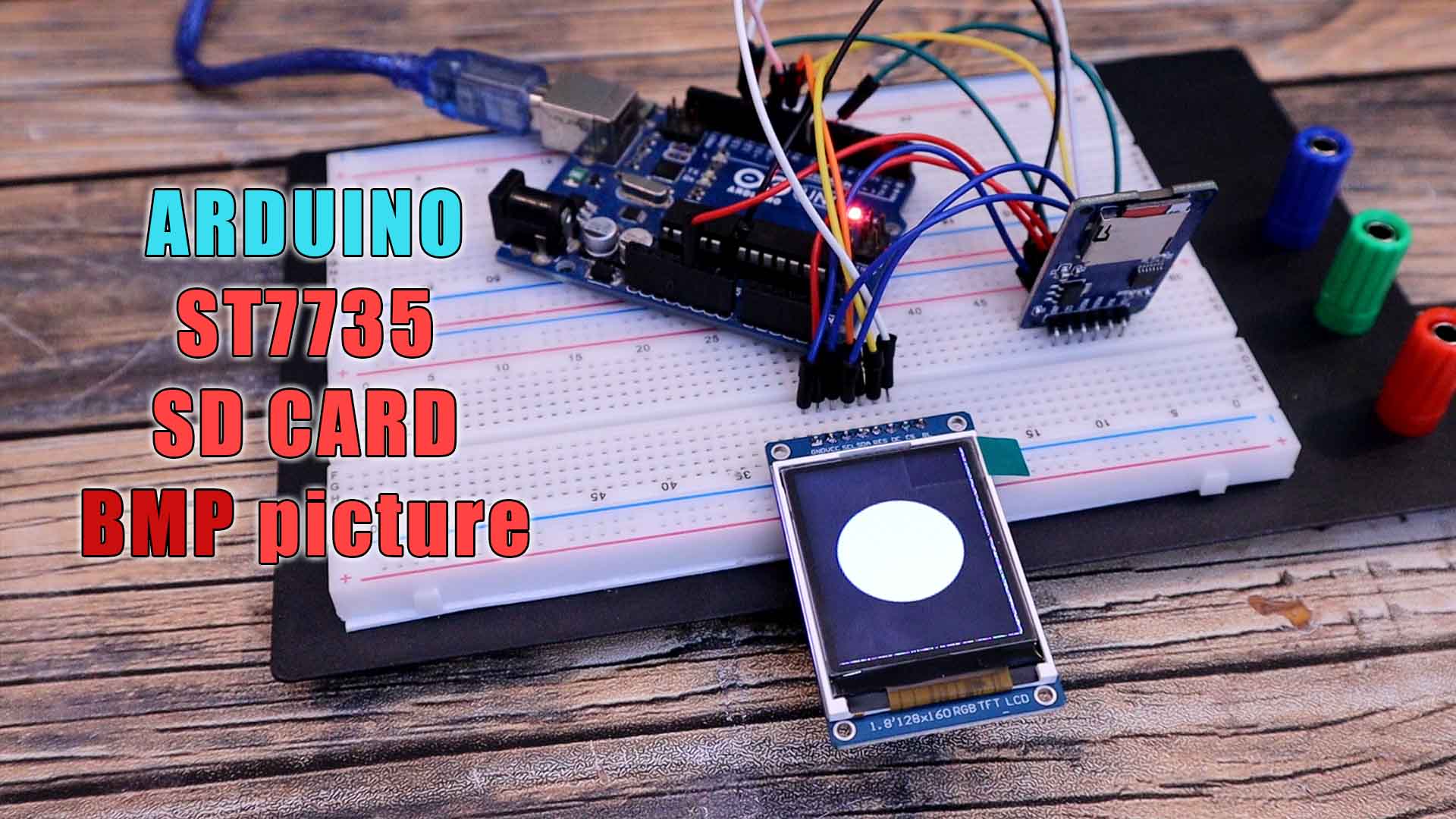

In this guide we’re going to show you how you can use the 1.8 TFT display with the Arduino. You’ll learn how to wire the display, write text, draw shapes and display images on the screen.

The 1.8 TFT is a colorful display with 128 x 160 color pixels. The display can load images from an SD card – it has an SD card slot at the back. The following figure shows the screen front and back view.

This module uses SPI communication – see the wiring below . To control the display we’ll use the TFT library, which is already included with Arduino IDE 1.0.5 and later.

The TFT display communicates with the Arduino via SPI communication, so you need to include the SPI library on your code. We also use the TFT library to write and draw on the display.

The 1.8 TFT display can load images from the SD card. To read from the SD card you use the SD library, already included in the Arduino IDE software. Follow the next steps to display an image on the display:

In this guide we’ve shown you how to use the 1.8 TFT display with the Arduino: display text, draw shapes and display images. You can easily add a nice visual interface to your projects using this display.

Stop-motion animation is the reverse process of freezing motion: such an animation is produced by displaying successive picture frames at high speed. Here we bring back to life Muybridges’ Sallie Gardner with the aid of a microcontroller connected to a suitable display. Several displays were tested with the ‘Sallie Gardner’ sketch running on an Arduino Uno, Nano or a Wemos D1 mini with an ESP8266 microprocessor chip.

Arduinos are designed to microprocess: they receive data, calculate, and communicate. Output through a display is limited since Arduinos lack a graphical processor. All the hard work in a common Arduino (Uno, Nano) is performed by a single 8-bit processor (ATmega 328) that has limited memory: 1kB EEPROM, 2kB SRAM (‘dynamic memory’) and 32kB flash memory (‘program memory’).

Programs are loaded in program memory while variables are created and during runtime stored in dynamic memory. Users have to live with the dynamic and program memory constraints offered by a common Arduino, or they can switch to an Arduino ‘Mega’ with an ATmega2560 microprocessor (256 kB flash and 8kB SRAM). One jump higher on the ladder is the family of ESP8266 based microboards, e.g., the Wemos D1 mini: 4 MB of SRAM and 50 kB of flash memory.

The challenge in the current project was to achieve fluent stop-motion animation featuring Sallie Gardner, using a humble Arduino Nano, and to see how well the animation performs with several displays. For this purpose I had available a 128*64 pixel LCD display with ST7920 controller, a 128*64 hybrid OLED display with SSD1306 controller, a 130*130 SSD TFT screen with 1283A controller, a 240*240 pixel TFT display powered by a SSD1283A chip, and several larger Arduino compatible TFT displays driven by ILI controllers

Our LCD display limits images to 128×64 pixels. The original ‘The Horse in Motion’ picture is an eight-bit gray scale jpg file from which we have to cut out frames to produce the animation bitmaps. Each cut-out frame produces a file with a size of 19 kB. Eleven of these files take 198 kB which is far beyond the amount of memory available in program space of an Arduino Nano. One solution for this is to load the files one after another from sd card, but the time consumed by this process would produce a slide show rather than the illusion of motion. A better solution is to load image frames from a separate .cpp file that needs to reside in the same directory as the sketch. The third approach, used in this paper, is to include the images in the sketch. One way or another, we need to reduce the image frames for our stop-motion animation to dimensions of 128×64 pixels or less to fit the screen.

A major consideration is that LCDs and OLEDs typically work with pixels that are either ON or OFF, that is, these devices require one-bit images: black / white. One-bit images are also called ‘monochrome’.

The combination all these considerations leads to the need to cut Muybridge’s ‘The Horse in Motion’ photograph down to eleven 1-bit frames each 128 pixels wide and 64 pixels high. Smaller frames are allowed; an advantage of smaller frames is faster loading in the LCD and, for that matter, a smoother animation.

figure 2. Direct bitmap conversion from 8-bit gray level to 1-bit (monochrome) wherein the final image is a 96×64 pixel image. The conversion produces ‘dithering’ which as a ‘spray’ of black pixels mimics grey shades.

The ‘The Horse in Motion’ photograph as I acquired it from wikipedia is a grayscale, eight-bit JPG formatted file*. If we cut a frame, say Sallie Gardner nr. 11, out of the original picture with for instance Photoshop or The Gimp and reduce it to a size that fits a 128*64 screen we can subsequently export the image in monochrome bitmap format. Here, export filters dither grey tones, that is, they produces speckles sprayed in the image to sort of mimic grey shades (figure 2). The amount of dithering can be reduced by enhancing contrast and intensity of the original cut before applying the export filter. In most cases the monochrome image files need some retouch step to remove traces of dithering. The preferred format of the output image files is Microsoft bmp. Note that these monochrome images are not nicely scalable, that is, if one attempts to do that the horse becomes a stack of big black squares. Anti-aliasing can not be applied to monochrome images.

figure 3. Import of a cut-out frame (nr. 11) of the original picture in a vector program is followed by manual segmentation (upper right; red contour). Subsequent deletion of the original bitmap produces a vector contour that can be scaled indefinitely without loss of sharpness. This vector image can then be exported to 1-bit monochrome bmp image format. If your vector drawing programs doesn’t have a monochrome bitmap export filter you will need extra software to convert the export file into proper monochrome bmp.

figure 4. Illustration of the vector procedure. Upper part: closed contour drawings of the horse and its rider are prepared in the vector drawing program as overlay for each frame of Muybridge’s original photograph. Lower part: the underlying bitmap is deleted, a 2:1 proportion frame added and export to 1-bit bitmap files can start. Note that a big advantage of vector images (the contour drawings) is that they remain scalable without loss of quality.

9. Scale the entire stack such that animation frame bitmaps, when exported, satisfy the conditions for LCD display: maximum width 128 pixels, maximum height 64 pixels. In the case of Sallie Gardner the scaling was conducted such that exported animation frame images measured 96×64 pixels, that is: height is here the limiting factor for the Sallie Gardner animation frames.

An intermediate, monitoring step is to check with an animated GIF creating program whether all export actions have been executed correctly and indeed have produced the 1-bit monochrome bitmaps that we need for the animation. I use Fiji (ImageJ) for this purpose. Fiji is a wonderful, free, open source cross platform imaging suite built on a Java platform (https://imagej.net/Fiji). One can also check with an animated GIF how fluid the movements in the Arduino animation will be. Small corrections can at this point be made in the vector file to get the very best out of the animation.

While Arduinos can work with bitmap files loaded from sd card, the loading and processing from sd card is is not fast enough to support animation. The monochrome images that we have produced need to be embedded in the sketch in 8-bit hexadecimal code (so-called ‘c-array’), or as ‘extern’ in the sketch folder

Conversion from bitmap to hexadecimal code is done with the program lcd-image-converter (freely available at https://sourceforge.net/projects/lcd-image-converter/). There exist also on line conversion tools.

Output of lcd-image-converter is a c-array file that, because it is in plain ascii text format, can be opened in any ascii editor (Notepad, Notepad++, Gedit) (figure 5).

The c-array starts with a variable: static const uint8_t, followed by the image’s file name and size (between the brackets). File size of each c-array is 768 bytes which will result in an animation that has 11×768 bytes = 8,448 bytes. With an Arduino Uno or Nano these c-arrays must be placed in program memory because the dynamic memory can hold only 2 kB of information.

figure 5. C-array file opened with an ascii editor (gedit). Frame 0. Left column: the entire c-array file listed. C-array files are composed as follows: top section: array information (commented), middle section: visual output (commented). All you need is in fact to copy-paste the bottom section: hex code array (pink) into the Arduino sketch.

If an array is defined in a sketch it will by default be compiled by the Arduino IDE to run in dynamic memory. As shown above, each frame of our animation requires 768 bytes. All the c-arrays must be placed in in program memory as constant unsigned chars. To achieve this the library

The stop-motion was initially developed on a 128*64 LCD, just out of curiosity to know in the first place whether it was possible to create an animation on technology so limited in graphic display. The library available to work with the 128*64LCD is

The complete sketch for the 128*64 ST7920 LCD wired to an Arduino Nano is supplied at the end of this document. You will find also versions of the sketch compatible with different display / microprocessor combinations. All these sketches contain the hexadecimal c-array description for each frame. I have added for each frame in a series of commented lines of empty and black characters a visual impression of how the frame looks like.

From the beginning it was evident that frame nr. 11 of “The Horse in Motion” would not contribute to a fluent animation. I assumed that each of the other frames would smoothly transfer to the next and that each animation cycle of frames would smoothly overflow into the next. However, the prototype sketch running on an Arduino Nano that powers a 128*64 LCD with ST7920 controller (figure 6), hiccuped at the point where it cycles from the last frame to the first. The cause appeared to be frame nr. 0 that seems to be atypical. Maybe this frame has been included by Muybridge to produce an appealing 4×3 photomontage. Who knows. Anyway, after frame nr 0 was excluded a very smoothly running animation remained. At this point I decided to include only frames 1 through 10 in the final animation. After completion of the prototyping work the ‘production’ sketch was adapted to run on a variety of combinations of microprocessor boards and displays at hand. A selection of the tested displays is shown in figure 6 while the table below provides the essentials of the tested devices.

Running the animation on the 128*64 LCD requires reference to the

Also on the 128*64 OLED with the SSD1306 controller the horse gallops fast and friendly under the

The 130*130 TFT display has a SSD1283A controller that needs the

Equestrian performance on the 130*130 TFT display connected to a Wemos D1 Mini did not produce faster animation than with a Nano as engine. In sketches written for the Wemos D1 Mini one is free to use the PROGMEM instruction. This microprocessor board has plenty SRAM available for the animation job. If PROGMEM was left out and all frame arrays were loaded as variables in dynamic memory instead of program memory, one might expect a faster animation. This however did not materialize: the speed of the animation did not change.

On the TFT display with more pixels (240*240-ST7789) the results were disappointing. Screen updates between every frame that sweep the entire screen instead of the 128×64 pixel ‘Sallie Gardner’ were markedly visible. On the 2.4, 2.8, 3.5 and 3.95 inch 240×320 and 320×480 pixel TFT displays (shields) with ILI controllers, including the 3.95 inch 320×480 ILI6814 screen, animation speed was grandiose, thanks to the support of David Prentice’s

figure 6. Animation played on several displays in combination with either Arduino Uno or Nano, or with a Wemos D1 Mini. While all these images measure 96 pixels in width and 64 pixels in height the size of their appearance is different because of pixel dimensions in these displays. The speed of the animation differs sharply between displays depending on the ‘efficiency’ of the library included in the sketch. The head of the jockey on the OLED is yellow because this display is of the hybrid, blue-yellow type.

The 128*64 LCD is a relatively big display with in proportion big LCD pixels. The OLED, 130*130 TFT and 240*240 TFT are devices with one-inch diagonal screens where the 240*240 TFT stands out with minuscule pixels that provide extreme sharpness. Sallie Gardner will certainly win a horse race on 320*480 TFT screens with my sketches compared with the LCD, OLED and small TFTs. The secret here is that on the TFT displays running under the

Searching the internet for other Muybridge horse animations for the Arduino I encountered in the Arduino forum a sketch for the Adafruit 128*64 OLED created in 2016 by Greg Stievenart and featuring ‘Annie G’, another galloping race horse, from Muybridge’s book “Animal Locomotion” (1887), plate 626; Muybridge has published hundreds of montage pictures of all kinds of animals and humans in motion; Sallie Gardner was only the premiere of his gigantic oevre. See https://forum.arduino.cc/index.php?topic=375985.0. Greg uses the method wherein the c-arrays are separate, external files. This works fine.

Most of the work to produce an animation is invested in the preparation of the frames. The limitations as far as Arduinos concerned are display size, c-array size, available memory in the microprocessor board, number and size of the frames, display controller speed and, finally, the efficiency of the library that contains the graphical and bitmap functions that govern printing each c-array to the display. Quite a handful of constraints! This makes it the more challenging and simultaneously more fun to continue working with small microprocessor boards. An animation is a chain of events in which the slowest link determines the outcome, that is a smooth and elegant animation.

As I had mentioned in one of my prior posts, I had been using Paul Stoffregen’s ILI9341_t3 library to drive data on the TFT display, and for the purposes of static information (pictures, text, whatever) it was more than sufficient. However, animation of these elements would prove to be a significant obstacle. The basic idea about how these screens work is that you push information to them and they stay in that state until something overwrites them. A basic instance is a single pixel – you can tell it to display a red color, and it will do so indefinitely so long as the device remains powered and it does not receive any subsequent data to change that specific pixel to a different color. However, this means that any region that might be subject to animation is essentially a three-step process:Draw the initial graphical element;

If you have the memory for it, you can basically create a ‘frame buffer’, or memory construct that can do these calculations invisibly, and once they are done simply update the necessary result to the screen. However, a 240 x 320 screen is 76,800 pixels, and it probably goes without saying that even with the expanded memory of a Teensy 3.2, we don’t have the necessary overhead for that kind of process here. Another approach you can take is to re-draw everything after a change, which does work, but ends up being hugely inefficient. As an example, anything that would cross over the UI lines would necessitate the UI lines be re-drawn. You can call the function that draws the UI, but it will end up re-drawing the UI lines on the entire display, which in the context of animation begins to cause a flickering effect as these areas are continually re-drawn. Not great.

With the use of the clipping region prior, the exact same function call now only draws on a portion of the screen. This is a practically small change, but has huge implications. Now, we can set a clipping region and only re-draw the areas of the screen that may require it for animation as necessary. This all but eliminates any display flickering, as it is no longer trying to update things across the entire 240×320 space of the screen, but a much smaller area instead.

In order for this to work, a large number of the basic drawing functions all had to be re-written to include a preliminary check at the beginning to see if the area about to be drawn is inside the ‘approved’ clipping region. It took me an afternoon of careful splicing, but I was able to extract the clipping region code from KurtE’s library and built it into my local version of the TFT library I had been using. For something like the writeRect function in the image example above, this is a sample of the type of code that needed to be inserted:

As a practical matter, I had some concerns that there would still be a fair bit of device slowdown, as even if you’re not drawing outside of the clipping region the functions still have to sweep progressively through the bitmap data to figure out what needs to be drawn. In practice, Kurt’s code is smartly designed to minimize the amount of time spent passing through any areas outside the clipping region, such that there is virtually no hit to performance that I was able to detect. I had to leave most of the rest of his library modifications out of my code as they wouldn’t work for the Teensy 3.2, but it’s safe to say that without this extra functionality I wouldn’t have been able to do most of what I have accomplished with the screen to date.

Animation is not just changing information on a screen, but also a function of change over time. You can control time constraints inside an Arduino environment with a simple delay(); call, which allows you to basically stop whatever it’s doing for that period. Say, for example, you had an object, and wanted to move its X position from 0 to 100. You could simply increment the x variable of that object in a loop, and after each change you could ask the microcontroller to delay(100); to make sure it moved at the pace you wanted it to across the screen. The problem arises, however, when you have multiple things that you’re asking the microcontroller to do at once. During a delay() call, nothing is calculated or advanced. No other elements could move simultaneously on the screen. Even button presses from the user would go ignored, which would make for a very frustrating experience. This is called ‘blocking’ in arduino parlance, and there are a number of resources that do a much better job of explaining the concept and issues here than I can afford the time for.

The way we typically deal with these scenarios is to avoid the use of delay() entirely. Instead, we create timers on the arduino by using the millis() command, which reads the number of milliseconds since the program started. This gives you an absolute reference to a value of time that is always increasing, and based on this value you can determine if enough time has passed to actually take a step in multiple different, simultaneous processes. To give you a pseudocode example:

Kurt’s was not the only library I was able to integrate and take advantage of. Although it’s entirely possible to do all of the above timing without any fancy library assistance, it becomes cumbersome. I adopted pfeerick’s elapsedMillis library to help me with the tracking of separate animation loops, which dramatically simplified the work involved. Now, each loop could simply have a designated timer object assigned to it, and each timer could easily be reset after the associated functions were run, all with basically a single line of code each. Way less of a headache.

Another aspect of animation is the idea of easing. Simply moving an object from X = 0 to X = 100 by increment the value of X is fine, and it will move in a linear fashion from start to finish. However, it will look unnatural; nothing in nature moves linearly from one point to another. In reality, things tend to accelerate or decelerate as they move. Our brains are wired to expect this kind of motion, so when animating we should be looking to duplicate these natural acceleration changes. Easing is a way to simulate this effect by replacing these linear changes with ones that ebb and flow. From what I have seen, a large amount of modern easing calculations stem from Robert Penner’s Easing Functions. Robert is a figure from Ye Olde Days of Macromedia Flash and the early internet, and he created a fairly comprehensive set of reusable easing functions that have been embraced in as many programming languages as I am aware of. The idea is that you simply feed the function your start current time (in whatever form you want to use – it can be seconds, steps of a process, any measurable interval), a start value, the desired total change in value, and the total duration, and it’ll spit out the required result for how far along in the animation you are. Gizma.com has a really straightforward interactive demo of how easing works that you can play around with to get the general idea of how these play out in practice. I tracked down an Easing library on GitHub by user “chicoplusplus” which included these functions in a tidy and accessible way for arduino usage, and tacked it into the VK’s program.

The final library I leaned on here was one simply called “Bounce2” by Thomas Fredericks. This one is a bit more esoteric in nature, and has nothing to do with animation, despite what you might think. Instead, it handles button input on the arduino.

The primary article on the Arduino.cc page does a good job of explaining the issue, but the simple summary is that when you push a button, it doesn’t do exactly what you think it does.

Handily, the Teensy (and a number of other Arduino) have internal pull-up and pull-down resistors, so we can skip actually needing to add extra electronics components! Instead, we simply use the pinMode declaration:

One of the other significant changes since my last post was the discovery of additional functionality in the ILI9341_t3 library for alternative ways of drawing Bitmaps. Up til that point, I had been drawing multi-colored images with the drawBitmap() function, which took a uint8_t array of bitmap data and a single color and drew that information out in a top-to-bottom pass. This worked fine, but in order to draw an image with, say, four colors, you had to have four separate image arrays and call each one in sequence with the correct color. This was tedious and honestly a bit slow in terms of how quickly the images would appear on the screen.

Turns out, there are better ways of doing this! The writeRectBPP functions in the library are specifically designed for this kind of thing, but I didn’t realize it until I got well into reviewing how everything worked. The “BPP” part of the function stands for “bit-per-pixel”, and indicates the color depth of the drawing function in question. 1BPP is basically what I had been doing – you have two colors, generally “on” or “off” while drawing the bitmap. 2BPP expands that range to 4 colors, which is analogous to what I had been inadvertently doing before. But 4BPP… that is where things get interesting. That is the realm of 16 colors, which may not sound like an awful lot, but actually begins to make images actually look realistic, rather than something that’s coming off a Commodore 64.

The writeRect4BPP function looks for a uint8_t array of pixel data and also uses a uint16_t array to serve as a palette of colors while drawing. With this information, it can draw out a 16-color bitmap in a single pass far more efficiently than what I had been doing, and in a way that looked dramatically better. The only challenge to using this method was how to convert my images into the correct data formats for this method. I tried a number of methods before stumbling onto what appears to be the ideal tool for the job – a company called “SEGGER” has a bitmap conversion tool (“BMPCVTDEMO”) that makes this process extremelystraightforward.

You can trim the color palette down to 16 colors easily, and the software even allows you to save the bitmap as a .c file, which contains all of the necessary bitmap information in an unsigned char array, which happens to be equivalent to a uint8_t array like what the function is looking for.

With this in place, we can use the output from the bitmap conversion program pretty much directly, making my life substantially easier if I end up in a position where I am personalizing things like the user/operator image for potential clients or customers.

With the preliminary structural code changes outlined above out of the way, I had to dive into actually taking all of these separate pieces and making them move. The first obvious issue is how to animate screen-to-screen transitions – from the LAPD start screen to the main UI, or the main UI to the profile page, for example. Here’s where I uncovered a new trick inherent to the ILI9341 display: scrolling. Review of the datasheet for the device (page 123) reveals that the display driver built into the ILI9341 TFT actually has scrolling functionality, at least in the sense that it can move data up or down on the screen without changing the actual pixel data. By writing a command to the VSCRSADD memory address, you can give the device a vertical offset value and it will move the screen up by that amount in pixels, wrapping the overflow back around to the bottom of the screen. Here’s an example of the start screen offset by 120 pixels upwards to illustrate:

The eye analysis is one of the biggest parts of the actual animation process, and to that end received basically an entirely new class of variables and functions while I was setting everything up. In my mind, the way the portable Voight-Kampff scanner would function is in two big phases – one phase where it recorded or captured image data about the subject being scanned, and another phase where it analyzed that information. I wanted to make the whole thing a fairly dynamic event – the scene where the device is used in Blade Runner 2049 is during a brawl, and the target puts up a decent fight to resist being scanned. The image would have to sway and move, either to simulate the operator’s hand not being perfectly steady under those conditions, or the movement and struggle of the targeted suspect. Mirroring some of our current camera-phone or webcam technology, I thought the image should also go randomly in and out of focus as the device attempted to resolve a clear enough image of the eye.

During the initial ‘recording playback’ phase following the scan, all of these elements come into play. In simple algorithmic terms, there are separate functions and timers generating a random X and Y sway for the image, and a third that periodically adjusts the focus of the image. The images themselves are 140×140 pixels, but using the setClipRect() function are constrained to the 120×120 pixel region on the UI for the eye graphic, which means I can have a maximum of ten pixels sway up, down, left or right. In practice, I found that a maximum of about 5 or 6 pixels in either direction was plenty, and the full 10 ended up being a bit too much movement. The blur is something I played with a lot while I was setting it up – initially I had up to six levels of blur, to make it a really smooth transition, but that required a lot of bitmap data. In the end, I settled for having two levels of blur – a 1 pixel Gaussian blur, and a 2 pixel one – which felt good enough to get the idea across.

Then we step into the “zooming” phase of the animation. I ended up slightly borrowing the way this process looks from the demo reel Territory Studios (the company responsible for the film’s screen graphics) put together for Blade Runner 2049.

Basically, the vertical bar will sweep down from the top of the screen and, in my version, passes back up. As it sweeps, in the wake of the bar it leaves the image of a zoomed-in eye. These zoomed in images were pre-baked simply because the Teensy didn’t have the memory required to do advanced bitmap functions like scaling and interpolation in addition to everything else I was having it do.

I settled on two steps of zoom for what I needed, though that was more out of consideration of the available memory on the Teensy 3.2, rather than my own desire – I would have gladly put more intermediate bitmaps in otherwise.

I included a brief animation where it draws 50 or 60 red “+” marks on the lower half of the eye image as the scanner engages in another pass of ‘analysis’, this time searching for the Nexus ID. Once this pass is completed, and if the target is found to be a Replicant, it’ll highlight the discovered ID number on the eye in red, letter-by-letter. It also transcribes this data into another field on the left side of the screen as it goes.

In total, I’ve got 4 sets of eyes built into the device at the moment. I would have gone for more, but I’m simply constrained by memory. Even the Teensy’s beefy 256k of flash starts getting full when you are throwing as many 16-color bitmaps at it as I have been. Still, I think there’s a reasonably good variety here, and the device is configured to never do the same eye graphic twice in a row, so hopefully they don’t get stale.

The profile page has its own selection of animations, but most of them are dedicated to outputting the necessary text elements, and don’t have quite the same level of involved programming as the eye analysis animations, and therefore won’t be something I spend as much time going through. I will say that all of the information that gets displayed is pulled from a dialog file that is very easy to edit, and all of the output is responsive to any changes made to that dialog file. If I ever decided, for example, to re-write the text field at the bottom of the profile page that announces the device user has the authority to detain, identify, or retire individuals, I would simply have to make those changes in the dialog file and the animation and UI would update accordingly to ensure that everything fit and was spaced out properly. I may never end up using that functionality as I may never end up changing the text that’s there, but I know future-me will be grateful if I ever do need to do that.

“ILI9341 based TFT Touchscreen Display Shields are very popular low cost Display Shields for Arduino. Visuino has had support for them for quite a while, but I never had chance to write a Tutorial on how to use them. Recently however few people asked questions about using displays with Visuino, so I decided to make a tutorial. In this Tutorial, I will show you how easy it is, to connect the Shield to Arduino, and program it with Visuino to animate a Bitmap to move around on the Display.”

Hey guys, Nick here. welcome to educ8s.tv a channel dedicated to DIY electronics projects with Arduino, Raspberry Pi, ESP8266 and other popular boards. In today’s Arduino tutorial, we are going to learn how to display custom bitmap graphics on most of the popular screens/displays that are compatible with the Arduino using the Adafruit GFX library and/or the Adafruit TFTLCD library.

Being able to display a personal/customized bitmap graphics on a display is a very useful functionality that Adafruit’s GFX library offers. With this functionality, we can build projects that display our own logo, or that helps users better understand a particular task the project is performing, providing an all-round improved User experience for your Arduino or ESP8266 based project.

The procedure that I am going to describe in this tutorial works with all the color displays that are supported by Adafruit’s GFX library and it also works for displays that use the TFTLCD library from Adafruit with a little modification. Some of the displays which I own on which this procedure works include the color OLED display, the 1.8” ST7735 color TFT display, the 2.8” Color Touch Screen which I reviewed a few weeks ago and the 3.5” Color TFT display. For each of the screen mentioned above, I have at one time or the other in the past cover how to connect them in an Arduino tutorial and you should check those tutorials out as it may give you a better background knowledge into how each of this displays works.

For this tutorial, we will be using the 2.8″ TFT Display which offers a resolution of 320 x 340 pixels resolution and we will display bitmap image of a car as shown in the image below.

As earlier mentioned and can be seen from the video, this procedure works with other screens which are compatible with the AdafruitGFX library or the Adafruit TFTLCD library.

Before putting the bitmap on a display we will need to create them or convert an already existing image into a bitmap image after which we will convert the bitmap image into a hex file which can then be used in our Arduino code. There are several tools which can be used for the creation of bitmap images, the likes of Corel draw and paint.net to mention a few, but for this tutorial, we will be using the paint.net software.

We can also create a text-based bitmap for the title, using any font and any language, we only need to make sure that background of the text is black and the text itself is white for easy display.

We then save both files as .bmp with 24bits color, it is important to keep in mind that large bitmaps use up a lot of memory and may prevent your code from running properly so always keep the bitmaps as small as possible.

With the graphics ready, the next task is for us to convert the graphics into bit arrays so they can be used in the code. To do this, we will be using the Image to LCD bitmap converter Java utility developed by Adafruit.

Paste the copied data array in the graphics.c file and save. Since we have two graphics for this tutorial, paste the data array for the two graphics in the file, separating them with their names. Don’t forget to declare the type of data in the data array as cont unsigned char and to add PROGEM in front of it (as shown in the image below) to store the data in the program memory of the Arduino.

As earlier mentioned, this functionality can be achieved by using the Adafruit GFX library or making a slight modification to the Adafruit TFTLCD library. so we will need these libraries for this tutorial and they can be downloaded from the link below.

The GFX library from Adafruit offers a function called drawBitmap, which enables the display of a monochrome bitmap image on the display. We can’t load multicolor graphics with this function just single color graphics but we can change the color of the bitmap image itself and thus display our graphics in different colors. If the display you have does not support the Adafruit GFX library but supports the Adafruit TFTLCD library we will have to make a modification to the Arduino sketch which involves copying the code of the drawBitmap function from the GFX library and pasting it in our Arduino sketch so it becomes a user-defined function.

The drawBitmap function is the key ingredient to writing the code for this project and every other part of the code has been covered at one time or the other in other tutorials on this website. The drawBitmap function takes 6 arguments as shown in the code snippet below;

The first two are the x and y coordinates of a point on the screen where we want the image to be displayed. The next argument is the array in which the bitmap is loaded in our code, in this case, it will be the name of the car and the text array located in the graphics.c file. The next two arguments are the width and height of the bitmap in pixels, in other words, the resolution of the image. The last argument is the color of the bitmap, we can use any color we like. The bitmap data must be located in program memory since Arduino has a limited amount of RAM memory available. The function is used as shown in the code snippet below:

Since using the TFTLCD library to achieve the goals of this project is more complex, it’s probably better to do a full explanation of how to write the code using the procedure. Howbeit, the code for the two procedures is included in the folder under the download section.

Next, we declare the name of the graphics which will be used; car and title, at this stage, you should have added the bit array for this two bitmaps in the graphics.c file and the file should be located in the same sketch folder as this code.

Next, is the void loop function, under the loop function, we call the drawbitmap function to display the car and the text bitmap using different colors.

The last section of the code is the drawBitmap function itself, as earlier mentioned, to use the drawbitmap function with the Adafruit TFTLCD library, we need to copy the function’s code and paste into the Arduino sketch.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey