flicker free lcd monitors quotation

ViewSonic VP2785-4K looks promising (at 99% Adobe RGB), but it"s listed as flicker-free on ViewSonic UK site, but not on US site - I"m trying to confirm that with ViewSonic Support.

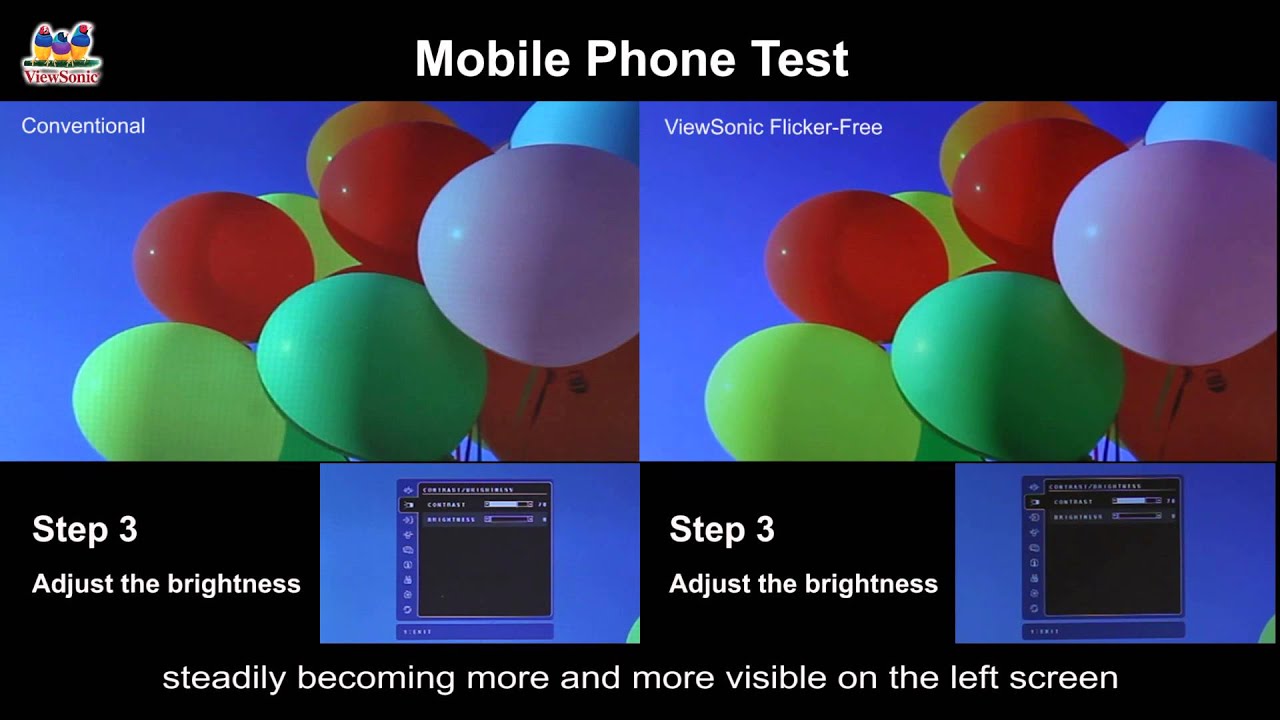

"Flickering is a characteristic of most LED screens. These screens used Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) to control the level of backlight brightness of the display. PWM works at a fixed frequency, turning the backlight on and off quickly to give the impression of reducing brightness. Flickering is not always apparent to the user because the refresh rate of many displays is too fast for human eye perception. Conventional monitors have a relatively long period between "on" and "off" states. "Traditional Flicker-Free" tries to mask the effects of flicker by increasing the frequency however this still causes the pupil to make rapid adjustments from large to small, affecting the autonomic nervous system and causing eye fatigue.

By integrating DC modulation LED backlights, the "on" "off" states of tradition flicker-free technology are completely removed. DC-modulation results in a constant stream of light, limiting the negative effects of using a computer for a prolonged period of time."

Backlight strobing, commonly known as black frame insertion (BFI), is an effect where the backlight flickers itself to try and improve the appearance of motion. We check for this in a separate test, but the BFI feature is tied into the flicker frequency; the only difference is that the image flicker is during regular use, while the BFI feature is usually something you can turn on and off. Below you can see an example of how introducing flicker on the LG 29UM69G-B helps improve the appearance of motion. However, there are times that the BFI features isn"t good and creates more image duplication, as you can see here.

Manufacturers implement different techniques of pulse width modulation, but one of the more common techniques is shortening the duty cycle. The duty cycle refers to the amount of time the pulse is sent for, and shortening the duty cycle reduces the intensity. Below are two examples from TVs that use different types of PWM, but the same techniques are applied with monitors that use PWM. You can see with the LG that the backlight flickers at all brightness levels, and the difference between the 100%, 50%, and 0% luminosity is the duty cycle. The backlight stays on for less time as you decrease the brightness. The Vizio starts to flicker at lower brightness levels with a short duty cycle, and by the time it reaches 0%, the cycle is almost 0.

A monitor can introduce image flicker at lower backlight levels, even if it"s flicker-free at its max brightness. If you"re concerned that your monitor flickers at lower backlight levels, set the brightness setting to its lowest, and wave your hand (or any object) in front of the screen. If you notice your hand is moving like it"s in front of a strobe light, then it has flicker. Increase the backlight until you don"t see this. If you don"t see this effect, then there"s no flicker.

We test the flicker on TVs similar to monitors, but on TVs, we also check to see which backlight setting the flicker starts at. We don"t do that for monitors. You can use the test above to see when the flicker starts exactly.

This test is meant for LED-backlit displays and not OLEDs because they don"t have a backlight. Still, OLED monitors get a perfect 10 because they don"t have any flicker.

LED-backlit monitors have a backlight to display an image on the screen. Sometimes, these monitors will use a technique called pulse width modulation in order to dim the backlight, where it sends short impulses, creating a flicker effect. We want to know which monitors do this and at which frequencies the backlight flickers. Most monitors we"ve tested are completely flicker-free, but there are a few that flicker. Introducing flicker can help with the appearance of motion but may also create eye strain, so having a monitor that flickers or not is entirely up to you.

ASUS Eye Care Monitors Receive Most Number of TÜV Rheinland Low Blue-Light Emissions and Flicker-Free Certifications. ASUS Low Blue Light Monitors feature a OSD menu that allows you to access four different Blue Light Filter settings onscreen. ASUS Flicker-Free technology uses Smart Dynamic Backlight Adjustment to reduce flicker, this protects you from eye fatigue, irritation and strains.

The wide range of conditions over which LCD monitors are used means that it is desirable to produce displays whose luminance (brightness) can be altered to match both bright and dim environments. This allows a user to set the screen to a comfortable level of brightness depending on their working conditions and ambient lighting. Manufacturers will normally quote a maximum brightness figure in their display specification, but it is also important to consider the lower range of adjustments possible from the screen as you would probably never want to use it at its highest setting. Indeed with specs often ranging up to 500 cd/m2, you will certainly need to use the screen at something a little less harsh on the eyes. As a reminder, we test the full range of backlight adjustments and the corresponding brightness values during each of our reviews. During our calibration process as well we try to adjust the screen to a setting of 120 cd/m2 which is considered the recommended luminance for an LCD monitor in normal lighting conditions. This process helps to give you an idea of what adjustments you need to make to the screen in order to return a luminance which you might actually want to use day to day.

Changing the display luminance is achieved by reducing the total light output for both CCFL- and LED-based backlights. By far the most prevalent technique for dimming the backlight is called Pulse Width Modulation (PWM), which has been in use for many years in desktop and laptop displays. However, this technique is not without some issues and the introduction of displays with high brightness levels and the popularisation of LED backlights has made the side-effects of PWM more visible than before, and in some cases may be a source of visible flicker, eyestrain, eye fatigue, headaches and other associated issues for people sensitive to it. This article is not intended to alarm, but is intended to show how PWM works and why it is used, as well as how to test a display to see its effects more clearly. We will also take a look at the methods some manufacturers are now adopting to address these concerns and provide flicker-free backlights instead. As awareness grows, more and more manufacturers are focusing on eye health with their monitor ranges.

1) Frequency –The backlight is cycled on and off very rapidly, and this cycling typically occurs at a fixed frequency (in Hz). How fast this cycling occurs can impact whether flicker is visible or perceivable to the user, with higher frequencies being potentially less problematic. PWM has been known to operate at low frequencies of 180 – 240Hz for example which are likely to be more problematic than higher frequencies ranging up in to the Kilohertz range (e.g. 18,000Hz).

3) Duty Cycle – The fraction of each cycle for which the backlight is in an “on” state is called the duty cycle. By altering this duty cycle the total light output of the backlight can be changed. As you reduce the brightness to reach a lower luminance, the duty cycle becomes progressively shorter, and the time for which the backlight is on becomes shorter, while the time for which it is off is longer. This technique works visually since cycling the backlight on and off sufficiently fast means the user cannot see this flickering, because it lies above their flicker-fusion threshold (more on this later).

The analogue (non-PWM) graphs corresponding to these perceived luminance levels would appear as shown below. In this case there is no modulation. This is the method used for flicker-free backlights which we will discuss more a little later.

CCFL backlights can be dimmed by reducing the current through the bulb, but only by about a factor of 2 because of their strict current and voltage requirements. This leaves PWM as the only simple method of achieving a large range of luminance. A CCFL bulb is in fact normally driven by the inverter to cycle on and off at a rate in the 10’s of kilohertz and well outside the range of flicker visible to humans. However, the PWM cycling typically occurs at a much lower frequency, around 175Hz, which can produce artefacts visible to humans.

While PWM is attractive to hardware makers for the reasons outlined above, it can also introduce distracting visual effects if not used carefully. Flicker from LED backlights is typically much more visible than for older CCFL backlights at the same duty cycle because the LED’s are able to switch on and off much faster, and do not continue to “glow” after the power is cut off. This means that where the CCFL backlight showed rather smooth luminance variation, the LED version shows sharper transitions between on and off states. This is why more recently the subject of PWM has cropped up online and in reviews, since more and more displays are moving to W-LED backlighting units now.

Where the effect of flicker can really come into play is any time the user’s eyes are moving. Under constant illumination with no flickering (e.g. sunlight) the image is smoothly blurred and is how we normally perceive motion. However, when combined with a light source using PWM several discrete afterimages of the screen may be perceived simultaneously and reduce readability and the ability of the eyes to lock onto objects. From the earlier analysis of the CCFL backlighting we know that false colour may be introduced as well, even when the original image is monochromatic. Below are shown examples of how text might appear while the eyes are moving horizontally under different backlights.

It is important to remember that this is entirely due to the backlight, and the display itself is showing a static image. Often it is said that humans cannot see more than 24 frames per second (fps), which is not true and actually corresponds to the approximate frame rate needed to perceive continuous motion. In fact, while the eyes are moving (such as when reading) it is possible to see the effects of flicker at several hundred hertz. The ability to observe flicker varies greatly between individuals, and even depends on where a user is looking since peripheral vision is most sensitive.

So how fast is PWM cycling backlights on and off? This seems to depend on the backlight type used, with CCFL-based backlights nearly all cycling at 175Hz or 175 times per second. LED backlights have been reported typically running from 180 – 420Hz, with those at the lower end flickering much more visibly. Some have even faster frequencies of >2000Hz so it really can vary. While this might seem too fast to be visible, keep in mind that 175Hz is not much faster than the 100-120Hz flicker observed in lights connected directly to the mains power.

100-120Hz flickering of fluorescent lights has in fact been linked to symptoms such as severe eye strain and headaches in a portion of the population, which is why high-frequency ballast circuits were developed that provide almost continuous output. Using PWM at low frequencies negates the advantages of using these better ballasts in backlights because it turns an almost constant light source back into one that flickers. An additional consideration is that poor quality or defective ballasts in fluorescent backlights can produce audible noise. In many cases this is exacerbated when PWM is introduced since the electronics are now dealing with an additional frequency at which power usage is changing.

It is also important to distinguish the difference between flicker in CRT displays and CCFL and LED backlit TFT displays. While a CRT may flicker as low as 60Hz, only a small strip is illuminated at any time as the electron gun scans from top to bottom. With CCFL and LED backlit TFT displays the entire screen surface illuminates at once, meaning much more light is emitted over a short time. This can be more distracting than in CRTs in some cases, especially if short duty cycles are used.

The flicker itself in display backlights may be subtle and not easily perceptible for some people, but the natural variation in human vision seems to make it clearly visible to others. With the use of high-brightness LED’s on the rise it is becoming increasingly necessary to use short PWM duty cycles to control brightness, making flicker more of a problem. With users spending many hours every day looking at their monitors, shouldn’t we consider the long term effects of both perceptible and imperceptible flicker?

If you find PWM backlight flickering distracting or just want to see if reducing it makes reading on a monitor easier, I’d encourage you to try the following: Turn the brightness of your monitor up to maximum and disable any automatic brightness adjustments. Now use the colour correction available in your video card drivers or calibration device to reduce the brightness to normal levels (usually by adjusting the contrast slider). This will reduce the luminance and contrast of your monitor while leaving the backlight on as much as possible during PWM cycles. While not a long-term solution for most due to the decreased contrast, this technique can help to discover if a reduction in PWM usage is helpful.

A much better method of course would be to purchase a display not relying on PWM for dimming, or at least one which uses a much higher cycling frequency. Few manufacturers seem to have implemented PWM at frequencies that would limit visible artefacts (well above 500Hz for CCFL and above 2000 Hz for LED). Additionally, some displays using PWM do not use a 100% duty cycle even at full brightness, meaning they will always produce flicker. Several LED-based displays may in fact be currently available which do not use PWM, but until backlight frequency and modulation become listed in specifications it will be necessary to see the display in person. Some manufacturers promote “flicker free” monitors in their range (BenQ, Acer for example) which are designed to not use PWM at all and instead use a Direct Current (DC) method of backlight dimming. Other manufacturers such as Eizo talk about flicker free backlights but also list a hybrid solution for their backlight dimming, where PWM is used for some of the brightness adjustment range at the lower end. In fact it seems an increasingly common practice for a screen to be PWM free down to a certain point, and then fro PWM to be used to really drive down the minimum luminance from there.

An easy method of measuring the PWM frequency of a backlight would be ideal, and luckily it can be done using only a camera which allows manual control of the shutter speed. This can quickly and easily identify PWM frequencies in the lower range, but may not be suitable for high frequency PWM. It should be able to detect PWM up to at least 500Hz though, but anything above that may look like a solid block, suggesting no use of PWM, when in fact it might be just using a higher frequency. Further more complex methods such as our oscilloscope setup would be needed to validate flicker-free status for definite.

What we are doing with this technique is turning a temporal effect into a spatial one by moving the camera during capture. The only significant source of light during the image capture is the thin line on the display, which is exposed onto consecutive columns on the sensor. If the backlight is flickering, different columns will have different brightness or colour values determined by the backlight at the time it was exposed.

BenQ GW2760HS – W-LED backlight. At all brightness settings the luminance output is a flat line, showing no PWM is being used. This is part of BenQ’s flicker free range.

The oscilloscope graphs can also allow us to examine the behaviour of the luminance output. Above is a typical W-LED backlight dimmed to 0% where PWM is used. You can see the changes between on and off are very steep and sudden, as the LED backlight is able to turn on and off very rapidly. As we’ve already discussed this can lead to potentially more noticeable flicker and associated issues as the changes are more pronounced.

As we said at the beginning, this article is not designed to scare people away from modern LCD displays, rather to help inform people of this potential issue. With the growing popularity in W-LED backlit monitors it does seem to be causing more user complaints than older displays, and this is related to the PWM technique used and ultimately the type of backlight selected. Of course the problems which can potentially be caused by the use of PWM are not seen by everyone, and in fact I expect there are far more people who would never notice any of the symptoms than there are people who do. For those who do suffer from side effects including headaches and eye strain there is an explanation at least.

With the long term and proven success of a technology like Pulse Width Modulation, and the many years of use in CCFL displays we can’t see it being widely changed at any time soon to be honest, even with the popular move to W-LED backlit units. It is still a reliable method for controlling the backlight intensity and therefore offering a range of brightness adjustments which every user would want and need. Those who are concerned about its side effects or who have had problems with previous displays should try and consider the frequency of the PWM in their new display, or perhaps even try and find a screen where it is not used at all in backlight dimming. Some manufacturers are proactively addressing this concern through the use of flicker free backlights, and so options are emerging which do not use PWM.

Spatial uniformity of displayed luminance can vary widely between different makes and models of LCD, the major determinant of uniformity being the backlight scheme [34] (some older LCDs allowed VGA input and relied on built-in analog-to-digital conversion, also a potential source of noise). Two commonplace schemes are, first, direct backlighting, wherein a spatial array of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) and a diffuser screen sit behind the liquid crystal panel, and, second, edge illumination, wherein light emitted by a linear array of diodes at one of the display’s edges is spatially distributed via lightguide. We quantified the spatial uniformity of the CG247X by presenting low-, medium-, and high-luminance static test patches at nine display positions (Fig 2, inset) and using the LS-110 spot meter to measure the luminance of each patch. At each luminance tested, we calculated the grand average over all display positions, and divisively normalized measurements by that average. As illustrated in Fig 2, at medium- and high-luminance, the CG247X showed greater spatial uniformity than our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b): for the CG247X, spatial variation was 5.1% at medium and 3.5% at high luminance, whereas for the U2415b, variation was 8.1% at medium and 8.5% at high luminance. The uniformity of the two displays was comparable at low luminance (CG247X, 27% versus U2415b, 17%). Prior to normalization, there were, as expected, marked differences between low-, medium-, and high-luminance measurements. For example, at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) on the CG247X, low-luminance measurements ranged from 0.07 to 0.10 cd/m2, medium-luminance measurements ranged from 57.70 to 57.93 cd/m2, and high-luminance measurements ranged from 113.9 to 114.2 cd/m2 (Table 1). We also quantified spatial surround effects; using a tripod at 1 m, we measured displayed luminance at position 5 comparing large (1920-by-1200 pixels) and small (384-by-384 pixels) 100%-luminance patches. For CG247X, the mean of 10 large-patch measurements was 0.56 cd/m2 greater than that of 10 small-patch measurements (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01), i.e., an increase of 0.50%. For the U2415b, the increase was 0.71 cd/m2, i.e., 0.67% (two-sample t-test, p < 0.01).

In-plane switching (IPS) LCDs, like our CG247X and U2415b, enable larger viewing angles than older LCD technology (e.g., twisted-nematic displays) [23]. To do so, IPS displays interdigitate electrodes (see 23]. For the displays we tested, vendor-issued specifications state a viewing angle of 178 deg, however, in the absence of further details, that derived measure is difficult to assimilate. We measured displayed luminance as a function of viewing angle over a range of azimuth and elevation (±60 deg). We fit a circular von Mises function (Fig 3, the CG247X and U2415b performed comparably in this regard. For the CG247X, the FW90M was 28.6 deg (fitted parameters: α = 1.45, κ = 3.37) and 32.6 deg (α = 1.65, κ = 2.62) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. For the U2415b, the FW90M was 31.2 deg (α = 1.60, κ = 2.85) and 31.0 deg (α = 1.55, κ = 2.90) for azimuth and elevation, respectively. At high-luminance we made a reduced set of measurements, assuming rotational symmetry, varying azimuth or elevation from 0 to 60 deg. These additional measurements yielded similar FW90M estimates. This descriptive model can be used to select a viewing distance with tolerable attenuation due to viewing angle. For example, if the CG247X is viewed from 1 m, a stimulus presented at the top of the display’s vertical meridian (i.e., elevation = 9.2 deg) would, due to viewing angle, undergo luminance attenuation by a factor of 0.97.

A common misconception among vision researchers and clinicians is that LCDs do not flicker (i.e., that LCDs are temporally uniform). In fact, there are two major sources of flicker that can affect a LCD: first, backlight flicker which usually occurs at temporal frequencies (e.g., 1000 Hz) well beyond the critical flicker fusion frequency (e.g., Elze & Tanner [24], and Ghodrati, Morris, & Price [35]), and, second, the so-called frame response which occurs at the refresh rate of the display (here, 60 Hz) [23, 36]. Frame responses are largely attributable to an LCD’s inversion scheme: a feature of modern displays wherein the polarity of the video signal voltage applied to the liquid crystal material is inverted from one video frame to the next. This inversion minimises long-term degradation, or aging, of the display by minimizing the DC voltage across the liquid crystal elements. Frame inversion schemes typically have fine spatial structure, on the scale of individual pixels, making them mostly imperceptible (e.g., dot inversion schemes [36]). We quantified the temporal uniformity of the CG247X by presenting (nominally) static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset) and using the linearized photodiode device to measure displayed luminance over time. At each of 11 luminances (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made 10 one-second recordings, averaging the Fourier amplitude spectra of those 10 recordings. Fig 4 shows the average spectrum at each luminance. The spectra of the CG247X revealed a frame response comprising a 60 Hz component as well as harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. The response at 60 Hz varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking at a luminance of 50%. However, the CG247X appeared free of backlight modulations. This absence of backlight modulations freed us of the consequences of said modulations (often desynchronized with the frame refresh signal) on increment/decrement transitions between luminances (see Fig 5 in [24]). The spectra of our consumer-grade LCD also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, likely associated with the back light. This latter temporal nonuniformity increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch.

We presented nominally static test patches at display position 5 (Fig 2, inset), measuring luminance with a linearized photodiode device. At each luminance (0, 10, 20 … 100%) we made ten 1-second recordings, deriving the Fourier amplitude spectrum for each. Each spectrum illustrated is the average of 10 spectra. For each display, we normalized spectra such that 1000 corresponds to the DC component at 50% luminance; therefore, a value of 5.0 corresponds to approximately 0.15 cd/m2. The spectra of the CG247X (upper) revealed a frame response, comprising a 60 Hz component and harmonic components at integer multiples of 60 Hz. This frame response varied non-monotonically in amplitude with the luminance of the static test patch, peaking between 40 and 50% luminance. The spectra of the U2415b (lower) also revealed a frame response, as well as 1.2 kHz flicker, the amplitude of which increased linearly with the luminance of the static test patch (amplitudes above 5.0 are not shown, arrowheads). For the U2415b, mains noise (50 Hz) was apparent at high-luminance. lum., luminance.

In general, LCD response times—the duration of the rise or fall of a step from one luminance level to another—vary as a function of both step source and destination luminance. This nonlinear behaviour is owing largely to mechanisms of response time compensation (RTC) (e.g., the work of McCartney [25]), a feature of many modern LCDs designed to enhance video. RTC mechanisms speed luminance transitions by transiently altering the voltage applied to the liquid crystal associated with individual pixels (e.g., Fig 1 in [27]; Fig 5 in [24]). We measured the CG247X’s response times by presenting luminance steps—both increments and decrements—to the linearized photodiode device. Step source and destination took values 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100%. As illustrated in Fig 5, response times varied as a function of both luminance step source and destination. For example, stepping from 0% luminance to 25% luminance took 24.5 ms, stepping from 75% to 100% took 12.9 ms, and stepping from 25% to 0% took 8.1 ms. All of these steps are the same height, but response times differ markedly. Overall, the response times of our consumer-grade LCD were less than the CG247X response times. However, as we will illustrate below, faster is not better; although RTC mechanisms reduced the response times of our consumer-grade LCD, they contaminated displayed luminance with overshoot and undershoot artifacts which are problematic for many applications in clinical and experimental vision research, including the presentation of mean-modulated flicker. RTC mechanisms lower “black-white-black” and “grey-to-grey” response times, which are used to promote displays to the gaming community and other consumer markets.

(A) CG247X response times. The leftmost gray box (labelled “0%”) encompasses four points showing mean response times for transitions from source luminance = 0% to destination luminances = 25, 50, 75, and 100% (x axis). These rise times (upward triangles) decreased with increasing destination luminance. The gray box labelled “25%” shows mean response times of transitions from source luminance = 25% to destination luminances = 0, 50, 75, and 100%. The fall time (downward triangle), from 25% to 0% luminance, was less than the rise times. Overall, response times varied as a function of both source and destination luminance, as is generally expected of LCDs. We made 10 measurements at each source/destination luminance pair; error bars, where not obscured by symbols, mark the full range (from minimum to maximum) of these 10 measurements. (B) U2415b response times. Graphical conventions are as in A. Overall, U2415b response times were less than CG247X response times.

At the outset of this study, we made preliminary measurements similar to those illustrated in Fig 5. We noticed that rise and fall times straddling 50% luminance were approximately equal (e.g., rise time from 25% to 75% = 16.3 ms; fall time from 75% to 25% = 17.1 ms) which led us to wonder whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts. To better determine the CG247X’s potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker, and its susceptibility, or otherwise, to overshoot and undershoot artifacts typical of LCDs implementing RTC mechanisms, we presented mean-modulated flicker on both the CG247X and our consumer-grade display, using the linearized photodiode device to measure luminance over time. We used a flicker period of 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast ranging from 20 to 100%. As illustrated in Fig 6, the consumer-grade display’s luminance traces revealed overshoot and undershoot artifacts symptomatic of RTC. The CG247X’s luminance traces, however, appeared free of RTC artifacts. We used these traces to estimate response times specific to mean-modulated flicker, illustrated in Fig 7. Overall, CG247X rise and fall times were greater than those of our consumer-grade LCD. However, with the exception of 100% contrast, CG247X rise and fall times were approximately equal, indicating its potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker.

Flicker period = 20 frames (333.3 ms), and contrast = 20 to 100% in increments of 20 as marked. At 40% contrast, the arrowheads show examples of luminance step source and destination as used in the computation of response times (Fig 7). For each display, we normalized traces to the luminance step destination at 100% contrast. For the U2415b, over- and undershoot are readily apparent at low and moderate contrast. The CG247X, however, shows exponential rise and fall, regardless of contrast.

Overall, CG247X (A) rise (upward triangles) and fall (downward triangles) times were greater than U2415b (B) rise and fall times. With the exception of 100% contrast, CG247X rise and fall times were approximately equal, indicating its potential suitability for presenting mean-modulated flicker. Each symbol represents the mean of 10 measurements. Error bars, where not obscured by symbols, mark the full range (minimum to maximum) of the 10 measurements.

To further determine whether the CG247X could be used to display achromatic, mean-modulated flicker without the introduction of unworkable artifacts, we presented flicker at frequencies ranging from 0.94 to 30 Hz and contrasts ranging from 20 to 100%. We used recorded traces (similar to those in Fig 6) to derive cycle-averaged luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for all flicker frequencies, and for contrasts up to 80%. At 100% contrast, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicating that, at full contrast, the monitor is not suitable for presenting mean-modulated flicker. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from our consumer-grade LCD (Dell U2415b) varied as a function of flicker frequency at all contrasts tested; this variation is problematic for presenting achromatic, mean-modulated flicker. We also used CG247X traces to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance. In Fig 8, we illustrate how cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of loss of contrast. The consumer-grade LCD was affected by both changes in cycle-averaged luminance and loss of contrast.

We presented mean-modulated flicker at a range of flicker frequencies (0.94 to 30 Hz) and contrasts (20 to 100%). We used waveforms (e.g., Fig 6) recorded from the CG247X (A) to derive cycle-averaged luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using the cycle-averaged luminance of a “reference” waveform, that is, the response to contrast = 20% and flicker frequency = 0.94 Hz. This relatively low-contrast, low-frequency waveform was chosen as reference because it should be easily realized by both displays. For clarity, cycle-averaged responses for contrast = 40, 60, 80, and 100% are offset by -0.1, -0.2, -0.3, and -0.4 log units, respectively (arrowheads). As shown, cycle-averaged luminance was approximately constant for contrast = 20 to 80% at all flicker frequencies tested (0.94 to 30 Hz). At contrast = 100%, cycle-averaged luminance decreased with flicker frequency. Cycle-averaged luminance recorded from the consumer-grade U2415b (B) increased with flicker frequency at all contrasts tested. Graphical conventions are as in A. We used waveforms recorded from the CG247X (C) to derive cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance; we divisively normalized that derived measure using cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance of the reference waveform (20%, 0.94 Hz). As shown, at all contrasts tested (20 to 100%), cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance decreased with flicker frequency, indicative of a loss of effective contrast. Cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance recorded from the U2415b (D) revealed both increases and decreases to effective contrast with flicker frequency. Each symbol is the average of 10 measurements. (None of the data in panels C and D is offset.) We modeled cycle-average luminance and r.m.s. luminance on the CG247X as a causal exponential decay (Methods). This model comprised one free parameter, τ. For the illustrated fit (blue), τ = 6.6 ms. The red symbols in panel C (slightly offset rightward for clarity) show the result of a validation experiment (see

Taken together, Fig 8, and the traces used to derive the measures plotted there, indicated a simple relationship between nominal and displayed luminance on the CG247X, namely, that the latter was, simply, a low-pass-filtered version of the former. To test this hypothesis, we modeled the function transferring nominal luminance to displayed luminance as a causal, exponential decay (Methods). We optimized the single free parameter in this model, the time constant of the exponential decay (τ), by minimizing the sum of the squared error between the model-derived cycle-averaged mean luminance and cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, and those derived from the photodiode traces. For the CG247X, the fit is illustrated in Fig 8 (blue). There, the fitted parameter, τ, was 6.6 ms. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged luminance, we computed the root-mean-square error (RMSE) separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, the RMSE was negligibly small for contrasts from 20 to 80% (ranging from 6.0e-4 to 6.3e-3 normalized units). At 100% contrast, RMSE was highest at 0.093. This simple model was a poor fit to the U2415b, not illustrated in Fig 8. For the U2415b, RMSEs were high, ranging from 0.04 at 20% contrast to 0.15 at 60% contrast. To assess the fit to cycle-averaged r.m.s. luminance, we calculated the square of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, R2, separately at each flicker contrast. For the CG247X, R2 was high, ranging from 0.9965 to 0.9999. As expected, the same calculation for the U2415b was consistent with a poor fit; at its worst, R2 = 0.03.

To quantify the nonlinearities associated with high-contrast, mean-modulated flicker, and to quantify temporal dependence between frames, we used a paired-pulse paradigm [37, 38]. We presented paired biphasic luminance pulses at position 5 (Fig 2, inset), systematically varying the inter-pulse interval, T (Methods). We used the measured responses to individual pulses to predict paired-pulse responses, and to model the display’s nonlinearities we subtracted each paired-pulse response from its prediction. Fig 9 shows the nonlinear behaviour of the CG247X and, for comparison, that of our consumer-grade LCD. In our CG247X, a nonlinear mechanism appeared to speed the transition between white and black (100% and 0% luminance, respectively; leftmost upper panel in Fig 9B). When paired pulses were separated by 16.67 ms or more (the three rightmost upper panels in Fig 9B where predicted and displayed luminance are approximately equal), the CG247X behaved linearly, that is, we saw no evidence of temporal dependence between frames. In our consumer-grade LCD, a nonlinear mechanism appeared to attenuate the transition to white (100% luminance; leftmost lower panel in Fig 9B). This attenuation reconciles with Fig 6 (lower), which shows marked overshoot at moderate contrast (e.g., 60% contrast, middlemost panel of Fig 6), but a near absence of overshoot at high-contrast (rightmost panel of Fig 6). Compared to the CG247X, the U2415b’s nonlinearities were large in magnitude and long-lasting. Paired pulses separated by as much as 33.33 ms (the third lower panel in Fig 9B, where predicted and displayed luminance are unequal) evoked nonlinear behaviour in the U2415b, that is, we saw clear evidence of temporal dependence between frames.

The GW2270H VA LED monitor brings viewing pleasure to everyday work and play with exquisite details on the exterior and striking visual performance delivered by 3000:1 high contrast ratio, 178°/178°wide-viewing angle, dual HDMI and BenQ"s eye-caring design, which consists of BenQ‘s Flicker-free technology and Low Blue Light modes

The Flicker-free Technology eliminates flickering at all brightness levels and reduces eye fatigue effectively. Conventional LCD screens flicker at the rate of 200 times per second. Your eyes may not see the flickers but they can certainly feel them. So relieve your eyes from the uncomfortable flickering effect by switching to a BenQ Flicker-free monitor.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey