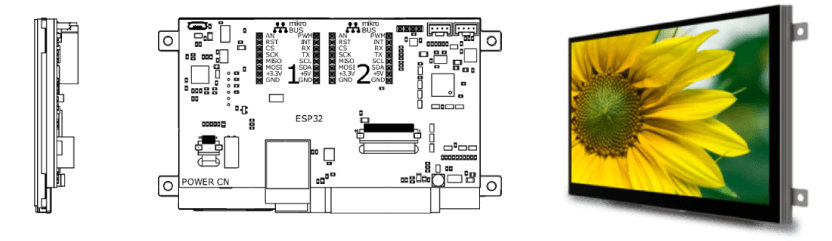

e3 commercial lcd displays free sample

The industry is flooded with manufacturers of varying capabilities, resources, commitment to quality and pre/post sales support. Some of these manufacturers will produce average quality displays without the needed enhancements that your customers expect today.

E3 Displays is all about making the manufacturing of your perfect display simple. We’ll guide you through an easy process to help you built your product so you never have to worry about low quality, inferior technology, unnecessary enhancements, and post sales continued support. Let’s make your business thrive.

Located at Hope Artiste Village in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, E3 Commercial Kitchen Solutions was founded in 2010 to proudly serve as a manufacturers’ representative to the commercial foodservice equipment industry. The space operates as a test kitchen and showroom for visiting clients. While on-site, clients can test the exclusive lines of restaurant equipment with E3 Corporate Chef, Josh Hill.

E3 represents some of the best-in-class manufacturers such as Alto-Shaam, Southbend, Wells, APW Wyott and many more. We were lucky enough to have the opportunity to speak with Equipment Specialist, Joe McDonald, and Chef Josh to discuss their favorite attributes of the business.

Joe describes E3 as a manufacturers’ representative firm that specializes in foodservice equipment. They cover the six New England states and promote and support the brands that the business represents. E3 and their employees work with end-users, and design consultants and dealers assist them with foodservice equipment solutions based on their applications.

The TriMark and E3 partnership works exceptionally well because both parties have the same goals, like (Joe outlines) “As a manufacturers’ rep group, we have always done business with TriMark – going back to the days of just United East. The benefit we look for is a true partnership where both the dealer and representative look to support each other to provide the end-user with the best product for their needs. We work together to help identify what that piece of equipment might be, by understanding the client’s business – where they are today and where they want to be tomorrow.”

The partnership has primarily been a success because it has always been a two-way street. Joe explains that E3 is often asked to get involved in equipment specifications and demonstrations at both the E3 test kitchen and TriMark Innovation Center in Boston. When TriMark leads with one of E3 manufacturers, we look to sell it based on its features and benefits, but most importantly because of how it fits the needs of our customer.

Along with partners Joe Burbine and Ken Lawler, McDonald is one of the principals of E3. His title is Equipment Specialist which entails understanding the needs of the end-user to find the best product that will meet those needs. Whether it is a dealer representative calling Joe for suggestions or working with them in the field, the common goal is to identify the product that can best support the final application. Understanding the goal of the operator is critical to whether E3 can be successful in the recommendations they make.

Another major part of Joe’s role includes being regularly involved with Chef Josh and the rest of the E3 team to run programs at their test kitchen. Their aim is to showcase and educate customers on either a specific product line or a group of lines and engage designers and consultants to emphasize product capabilities as well as the services that the E3 team can offer both pre-sale and post-sale. McDonald emphasizes the importance of product education so that people fully understand what the equipment can do and how it is essential to their success. The team spends a lot of time post-sale making sure the product is living up the consumer’s expectations. The primary goal is to see their end-users thrive and succeed.

McDonald is proud and invested in the E3 business. He attributes the success of the business to “the team and always trying to keep it fun. We work together and always try to do what is right and best for anyone we work with. We play to each other’s strengths and are never afraid to hand something off to another team member if we think they are the best person to handle the job”, Joe says. “The team members at E3 are more than colleagues; we are friends who genuinely care about each other and our families. Our team takes a lot of pride in what we do and it’s a great feeling to know you always have someone watching out for you and they are there when you need them. The fun we have together makes the harder days a lot easier to get through. The people I work with make me better at what I do, and I cannot say enough about how much respect I have for all of them. We are a TEAM.”

Performing the role of Corporate Chef, Josh handles all the culinary aspects of E3 including trainings, demos and culinary classes. He works with clients to test drive equipment and troubleshoot cooking applications in order to achieve maximum menu efficiency. Josh focuses on collaborating and interacting with consumers to streamline complex procedures into user-friendly settings.

Hill finds E3 a rewarding place to work on a variety of levels. To start, the business has a commitment to excellence – for both themselves and their customers. Josh also takes pride in collaborating with chefs. He enjoys teaching them new and innovative approaches to cooking; this allows him to pass along the practices and skills he has learned throughout his career. Lastly, he highlights the changing dynamic of the industry. There are constantly new prospects engaging with E3, which allows Josh to continually meet new people, travel to new places and build lasting relationships.

The industry"s most cost-effective, 43-inch high-brightness optical solution, reliable and stable quality, can effectively save commercial display research and development time.

Choose the Multipette E3 or E3x multi-dispenser pipette for all liquid types without compromising on accuracy and precision. These electronic positive displacement dispenser pipettes are ideal for stress-free, long series repetitive dispensing due to their lightweight, ergonomic design, and easy, motor driven action which reduces fatigue and the risk of repetitive strain injuries. The Multipette E3 and E3x have a wide dispensing range of 1 µL to 50 mL, 5,000 different dispensing volumes with increments as low as 100 nL and are used with Combitips® advanced positive displacement tips. With automatic tip recognition, the Multipette/Combitips system is ideal for all types of liquids, and by preventing aerosols from leaving the syringe-style tips, users can work safely with hazardous liquids and volatile solutions.

While the Multipette E3 already meets many application needs with its three main operating modes Dispensing, Automatic Dispensing and Pipetting, the Multipette E3x comes with four additional modes: Sequential Dispensing, Aspiration, Aspiration/Dispensing, and Titration. Both models use Combitips advanced and ensure easy, efficient and contamination-free liquid handling.

Combitips advanced tips easily attach to the Multipette E3/E3x electronic multi-dispenser pipettes. Their built-in sensor recognizes the size of the tip, and the volume appears automatically in the display - eliminating time-consuming volume calculations and incorrect dispensing volumes. Combitips advanced are available in nine sizes, allowing a wider dispensing range of up to 112 different volumes and longer series dispensing before needing to stop for a refill.

The Multipette/Combitips system provides the perfect solution for accurate dispensing of all types of liquid. Effortlessly fill plates or long series of tubes with the Multipette E3/E3x electronic multi-dispenser pipette, while maximizing pipetting accuracy and precision with the positive displacement Combitips advanced tip. With the Eppendorf Pipette Software Update Tool you can easily update your electronic Multipette and stay up to date with the latest software improvements and new features!

The packaging of Multipette E3/E3x dispensers contains different materials, including cardboard and plastic foil. Our Multipette packaging cardboard material consists of approx. 92 % recycling material. Please support the global sustainability initiative of recycling valuable raw material by collecting the cardboard and disposing of it in the appropriate collection container at your organization. In respect to the wrapping foils made of LD-PE, we recommend to select a dedicated recycling partner where PE material can be recycled.

Total OCPUs (cores) for Compute instances that use shapes in the VM.Standard.E3 and BM.Standard.E3 series and container instances that use the CI.Standard.E3.Flex shape

Total memory for Compute instances that use shapes in the VM.Standard.E3 and BM.Standard.E3 series and container instances that use the CI.Standard.E3.Flex shape

2,000 - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Italy Northwest (Milan),Japan Central (Osaka),Japan East (Tokyo), Netherlands Northwest (Amsterdam), Saudi Arabia West (Jeddah), Singapore (Singapore), South Korea Central (Seoul), Sweden Central (Stockholm), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

32,000 GB - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Italy Northwest (Milan),Japan Central (Osaka),Japan East (Tokyo), Netherlands Northwest (Amsterdam), Saudi Arabia West (Jeddah), Singapore (Singapore), South Korea Central (Seoul), Sweden Central (Stockholm), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

500 - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US West (San Jose))

6 - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

7,000 GB - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US West (San Jose))

84 GB - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

2,000 - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Italy Northwest (Milan),Japan Central (Osaka),Japan East (Tokyo), Netherlands Northwest (Amsterdam), Saudi Arabia West (Jeddah), Singapore (Singapore), South Korea Central (Seoul), Sweden Central (Stockholm), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

32,000 GB - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Italy Northwest (Milan),Japan Central (Osaka),Japan East (Tokyo), Netherlands Northwest (Amsterdam), Saudi Arabia West (Jeddah), Singapore (Singapore), South Korea Central (Seoul), Sweden Central (Stockholm), UK South (London), US East (Ashburn), US West (Phoenix), US West (San Jose))

500 - commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US West (San Jose))

7,000 GB commercial realm (Australia East (Sydney), Australia Southeast (Melbourne), Brazil East (Sao Paulo), Brazil Southeast (Vinhedo), Canada Southeast (Montreal), Canada Southeast (Toronto), France Central (Paris), France South (Marseille), Germany Central (Frankfurt), India South (Hyderabad), India West (Mumbai), Israel Central (Jerusalem), Italy Northwest (Milan), Japan Central (Osaka), Japan East (Tokyo), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa Central (Johannesburg), South Korea Central (Seoul), South Korea North (Chuncheon), Sweden Central (Stockholm), Switzerland North (Zurich), UAE East (Dubai), UK South (London), US West (San Jose))

Pay-as-You-Go or PromoTotal OCPUs (cores) for Compute instances that use shapes in the VM.Standard.E3 and BM.Standard.E3 series and container instances that use the CI.Standard.E3.Flex shape

Total memory for Compute instances that use shapes in the VM.Standard.E3 and BM.Standard.E3 series and container instances that use the CI.Standard.E3.Flex shape

Due to their role in many diseases, enzymes of the ubiquitin system have recently become interesting drug targets. Despite efforts, primary screenings of compound libraries targeting E2 enzymes and E3 ligases have been strongly limited by the lack of robust and fast high-throughput assays. Here we report a label-free high-throughput screening assay for ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases based on MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay allows testing E2 enzymes and E3 ligases for their ubiquitin transfer activity, identifying E2/E3 active pairs, inhibitor potency and specificity and screening compound libraries in vitro without chemical or fluorescent probes. We demonstrate that the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay is a universal tool for drug discovery screening in the ubiquitin pathway as it is suitable for working with all E3 ligase families and requires a reduced amount of reagents, compared with standard biochemical assays.

Ubiquitylation is a post-translational modification which impacts almost every biological process in the cell. Dysregulation of the ubiquitylation pathway is associated with several diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and immunological dysfunctions. Single ubiquitin moieties or polyubiquitin chains are added to the substrate by the combined action of three different classes of enzymes: the E1 activating enzymes, the E2s conjugating enzymes, and the E3 ligase enzymes (Pickart, 2001). In the first step, a single ubiquitin molecule is coupled to the active site of an E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme in an ATP-dependent reaction. In the second step, the ubiquitin molecule is transferred from E1 to an E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme. In the final step, ubiquitin is transferred to the protein substrate in a process mediated by an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which provides a binding platform for ubiquitin-charged E2 and the substrate. Ubiquitin chain formation is highly specific and regulated by a plethora of different E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases. The human genome encodes two ubiquitin-activating E1, >30 ubiquitin-specific E2, and 600–700 of E3 ligases (Kim et al., 2011). Thus, including about 100 deubiquitylating enzymes, approximately 800 ubiquitin enzymes regulate the dynamic ubiquitylation of a wide range of protein substrates (Kim et al., 2011). Within this complexity, E3 ligases are the most diverse class of enzymes in the ubiquitylation pathway as they play a central role in determining the selectivity of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation and signaling.

E3 ligases have been associated with a number of pathogenic mechanisms. Mutations in the E3 ligases MDM2, BRCA1, TRIMs, and Parkin have been linked to multiple cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (Fakharzadeh et al., 1991, Hatakeyama, 2011, Welcsh and King, 2001), and MDM2-p53 interaction inhibitors have already been developed as a potential anti-cancer treatment (Shangary and Wang, 2009). This highlights the potential of E2 enzymes and E3 ligases as drug targets. Although all E3 ligases are involved in the final step of covalent ubiquitylation of target proteins, they differ in both structure and mechanism and can be classified in three main families depending on the type of E3 ligases promoting ubiquitin-protein ligation and on the presence of characteristic domains. The RING ligases bring the ubiquitin-E2 complex into the molecular vicinity of the substrate and facilitate ubiquitin transfer directly from the E2 enzyme to the substrate protein. In contrast, homologous to the E6-AP C terminus family (HECTs) covalently bind the ubiquitin via a cysteine residue in their catalytic HECT domain before shuttling it onto the target molecule. RING between RINGs (RBRs) E3 ligases were shown to use both RING- and HECT-like mechanisms where ubiquitin is initially recruited on a RING domain (RING1) then transferred to the substrate through a conserved cysteine residue in a second RING domain. The vast majority of human E3 enzymes belong to the RING family, while only 28 belong to the HECT and 14 to the RBR family of E3 ligases (Chaugule and Walden, 2016).

Due to the high attractiveness of E2 and E3 ligases as drug targets, a number of drug discovery assays have been published, based on detection by fluorescence (Dudgeon et al., 2010, Krist et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2004), antibodies (Davydov et al., 2004, Huang et al., 2005, Kenten et al., 2005, Marblestone et al., 2010), tandem ubiquitin-binding entities (Heap et al., 2017a, Marblestone et al., 2012), surface plasmon resonance (Regnstrom et al., 2013), or cellular and bacterial two-hybrid (Levin-Kravets et al., 2016, Maculins et al., 2016). However, many of these tools are either too expensive for very high-throughput drug discovery or potentially result in false-positive and false-negative hits due to the use of non-physiological E2/E3 ligase substrates. We have addressed this gap by developing the first in vitro label-free MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry-based approach to screen the activity of E2 and E3 ligases that uses unmodified mono-ubiquitin as substrate. As a proof-of-concept, we screened a collection of 1,430 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for inhibitors of a subset of three E3 ligases that are clinically relevant and belong to three different E3 ligase families. The screen shows high reproducibility and robustness, and we were able to identify a subset of 15 molecules active against the E3 ligases tested. We validated the most powerful positive hits by determining the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values against their targets, confirming that bendamustine and candesartan cilexitel inhibit HOIP and MDM2, respectively, in in vitro conditions.

E2 and E3 ligase activity results in formation of free or attached polyubiquitin chains, mono-ubiquitylation, and/or multiple mono-ubiquitylation of a specific substrate. However, in absence of a specific substrate, most E3 ligases will either produce free polyubiquitin chains or undergo auto-ubiquitylation which is a mechanism thought to be responsible for the regulation of the E3 enzyme itself (de Bie and Ciechanover, 2011). Furthermore, there is some evidence that auto-ubiquitylation of E3 ligases is facilitating the recruitment of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (Ranaweera and Yang, 2013). Auto-ubiquitylation assays or free polyubiquitin chain production have been widely used to assess the E3 ligase potential of a protein (de Bie and Ciechanover, 2011, Lorick et al., 1999). We used this property of E2 and E3 ligases to design a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry-based high-throughput screening (HTS) method that allowed the reliable determination of activities of E2 and E3 ligase pairs by measuring the depleting intensity of mono-ubiquitin in the assay as a readout.

As proof-of-concept we used three E3 ligases belonging to different E3 families and representative of all the currently known ubiquitylation mechanisms. MDM2 is an RING-type E3 ligase which controls the stability of the transcription factor p53, a key tumor suppressor that is often found mutated in human cancers (Rivlin et al., 2011, Vogelstein et al., 2000). ITCH belongs to the HECT domain-containing E3 ligase family involved in the regulation of immunological response and cancer development (Hansen et al., 2007, Rivetti di Val Cervo et al., 2009, Rossi et al., 2009). Finally, HOIP, an RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase and member of the LUBAC (linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex). As part of the LUBAC complex, HOIP is involved in the regulation of important cellular signaling pathways that control innate immunity and inflammation through nuclear factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation and protection against tumor necrosis factor α-induced apoptosis (Kirisako et al., 2006, Tokunaga et al., 2009). HOIP is the only known E3 ligase generating linear ubiquitin chains (Ikeda et al., 2011). Because of that, fluorescent assays using C- or N-terminally labeled ubiquitin species cannot be used to form linear chains.

To determine MDM2, ITCH, and HOIP auto-ubiquitylation reaction rate and the linearity range we followed the consumption of mono-ubiquitin over time with increasing starting amount of mono-ubiquitin. We matched MDM2, ITCH, and HOIP with E2 conjugating enzymes as reported in the literature: MDM2 and ITCH were incubated with E2D1 (UbcH5a) (Honda et al., 1997), while HOIP was used in combination with UBE2L3 (UbcH7) (Kirisako et al., 2006). In brief, the in vitro ubiquitylation reaction consisted of 1 mM ATP, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.125 μM ubiquitin, 50 nM E1, 250 nM E2, and 250 or 500 nM E3 ligase enzyme at 37°C for 30 min in a total volume of 5 μL (Figure 1A). Reactions were started by addition of ubiquitin and terminated by addition of 2.5 μL of 10% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. A dose of 1.05 μL of each reaction was then spiked with 300 nL (4 μM) of 15N-labelled ubiquitin and 1.2 μL of 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone matrix and 250 nL of this solution was spotted onto a 1,536 μL plate MALDI anchor target using a nanoliter dispensing robot. The samples were analyzed by high mass accuracy MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (MS) in reflector positive ion mode on a rapifleX MALDI-TOF MS.

(A) Workflow of the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay. Each of the three E3 ligases were incubated with their E2 partner with different concentrations of mono-ubiquitin (12.5, 6.25, and 3.125 μM) at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by addition of 2.5 μL 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at different time points. Reaction aliquots (1.05 μL) were mixed with 150 nL of 1.5 μM 15N ubiquitin as internal standard. Subsequently, the analytes were mixed with 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone matrix and spotted onto a 1,536 AnchorChip MALDI target (Bruker Daltonics). Data analysis was performed using FlexAnalysis.

(B) E2/E3 ligase reactions are linear. Linearity is determined by mono-ubiquitin consumption over time. Only at very high and low concentrations of ubiquitin, the reaction is not linear. Data points have been normalized to determine reaction linearity. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

(C) Western blots of in vitro reactions (E1 100 nM, UBE2D1 250 nM, UBE2L3 125 nM, MDM2 and ITCH 500 nM, HOIP 250 nM, and ubiquitin 6.25 μM) of the three E3 ligases showing increased ubiquitin chain formation over time.

In our experimental conditions, ubiquitin consumption relied on the presence on an E3 ligase as we did not observe a significant reduction in the ubiquitin level within the negative controls (Figure 1B), where only E1 activating enzyme and E2 conjugating enzyme were present. Enzyme concentrations were optimized by reducing enzyme concentrations of previously reported SDS-PAGE auto-ubiquitylation assay protocols (Choo and Zhang, 2009, Zhao et al., 2012). An excess of ubiquitin (in the μM range) compared with the ubiquitin cascade enzymes (250 nM for HOIP, 500 nM for ITCH, and 500 nM for MDM2) was found necessary in order to control reaction velocity. As expected, we observed that ubiquitin consumption was dose and enzyme dependent (Figure 1B, Figures S1 and S2). Reaction rates were related to ubiquitin concentration (Table S1) and different enzymes showed different rates of ubiquitin consumption (Figure 1B).

The well-established E2-E3 auto-ubiquitylation assays followed by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis provided similar results, and we observed that the time-dependent disappearance of ubiquitin is comparable using both techniques (Figure 1C). Moreover, while substrate and enzyme concentrations are comparable with western blot-based approaches, the reaction volume (5 μL) is smaller than most of the antibody-based approaches currently reported in literature (Sheng et al., 2012).

E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzymes are the central players in the ubiquitin cascade (Stewart et al., 2016). The human genome encodes ∼40 E2 conjugating enzymes, of which about 30 conjugate ubiquitin directly while others conjugate small ubiquitin-like proteins such as SUMO1 and NEDD8 (Cappadocia and Lima, 2017). E2 enzymes are involved in every step of the ubiquitin chain formation pathway, from transferring the ubiquitin to mediating the switch from ubiquitin chain initiation to elongation, and defining the type of chain linkage. Connecting ubiquitin molecules in a defined manner by modifying specific Lys residues with ubiquitin is another intrinsic property of many E2 enzymes. Early studies showed that, at high concentrations, E2 enzymes can synthesize ubiquitin chains of a distinct linkage or undergo auto-ubiquitylation even in the absence of an E3 (Pickart and Rose, 1985), albeit at lower transfer rates (Stewart et al., 2016). This characteristic has been exploited for the generation of large amounts of different ubiquitin chain types in vitro (Faggiano et al., 2016).

As control for E2 enzyme mono or multi-ubiquitylation or E2-dependent ubiquitin chain assembly, we firstly assessed which E2 conjugating enzymes in our panel were able to consume ubiquitin even in absence of a partner E3 ligase. Utilizing the MALDI-TOF E2-E3 assay, we systematically tested 27 recombinantly expressed E2 conjugating enzymes (Table S2) for their ability to process ubiquitin either by the formation of polyubiquitin chains or by auto-ubiquitylation at different concentrations (250 nM, 500 nM, and 1 μM). We found that the UBE2Q1 and UBE2Q2 were able to consume ubiquitin even in absence of a specific E3 ligase at 250 nM after 45 min incubation time, and almost completely exhausting the starting ubiquitin amount after 2 hr of incubation (Figure 2). UBE2O and UBE2S are able to consume ubiquitin when present at a starting concentration of 500 nM, with consumption being evident from 90 min onward. Interestingly, UBE2Q1, UBE2Q2, and UBE2O (Berleth and Pickart, 1996, Klemperer et al., 1989, Melner et al., 2006) are E2 conjugating enzymes characterized by an unusually high molecular mass compared with other E2 enzymes: in particular, UBE2O has been reported as an E2-E3 hybrid which might explain its ability to form ubiquitin chains in the absence of an E3 ligase. Most of the E2 conjugating enzymes showed ubiquitin-consuming activity once their concentration was increased to 1 μM. Interestingly, UBE2D1 and UBE2L3 do not show any ligase activity, even at 1 μM, making these E2 conjugating enzymes the perfect candidates for inhibitor screening of E3 ligases as all ubiquitin-consuming activity in an assay will be down to E3 activity. Our results demonstrate that the E2-E3 MALDI-TOF assay has the potential to be employed for measuring E2 in vitro activity and therefore can be employed for screening inhibitors against those E2 enzymes that possess intrinsic ubiquitin ligase activity in vitro.

Any given E3 ligase cooperates with specific E2 enzymes in vivo. However, it is still difficult to predict which E2/E3 enzyme pair would be functional. Determining E2/E3 specificity is paramount to set up in vitro ubiquitylation assays and to perform inhibitor screens against E3 ligases. Using the E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay, we investigated the activity of MDM2, ITCH, and HOIP throughout 8 time points when incubated with any of 27 ubiquitin E2 enzymes, covering the majority of the reported classes/families (Figure 3). We arbitrarily defined “fully active” pairs any E2-E3 couple that completely depleted the mono-ubiquitin starting amount after 2 hr incubation time. The UBE2D family is reported in the literature as being able to productively interact with MDM2 (Marblestone et al., 2013), ITCH (Sheng et al., 2012), and HOIP (Lechtenberg et al., 2016). Our data showed that UBE2D1 and UBE2D2, also known as UBCH5a and UBCH5b, were fully active with all the E3 ligases under investigation confirming the promiscuous activity of this class of E2 enzymes that was previously reported in the literature (Lechtenberg et al., 2016, Marblestone et al., 2013, Sheng et al., 2012). The UBE2E family was only partially active against the E3s ligases of interest. The well-characterized human E2L3 (or UBCH7) showed activity with HOIP and ITCH, confirming the already reported UBCH7 ability of functioning with both HECT and RBR E3 families (Capili et al., 2004, Shimura et al., 2000). Taken together these results demonstrate that the E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay is suitable for determining E2 specificity toward their cognate E3 enzymes in a high-throughput fashion.

E1-E2 enzymes (50 and 250 nM, respectively) and E3 ligases were incubated in duplicate with 6.125 μM ubiquitin at 37°C for the time indicated. Reactions were stopped at the indicated time points with 2% TFA final and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Ligase activity was calculated considering T0 as 0% and the complete disappearance of mono-ubiquitin signal from the mass window as 100% activity.

We next evaluated whether the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay had the potential to assess the potency and selectivity of E2/E3 inhibitors. As proof-of-concept, we tested five inhibitors that had previously been reported to inhibit E1, E2, or E3 ligases: PYR41 (Yang et al., 2007), BAY117082 (Strickson et al., 2013), gliotoxin (Sakamoto et al., 2015), nutlin-3A (Vassilev et al., 2004), clomipramine (Rossi et al., 2014), and Compound 1 (Brownell et al., 2010). We also tested PR619 (Altun et al., 2011), a broad-spectrum, alkylating deubiquitylase (DUB) inhibitor, which we hypothesized would also inhibit other enzymes with active site cysteines, such as E1/E2 enzymes and E3 ligases. PYR41 is a specific and cell-permeable inhibitor of E1 ubiquitin loading but does not directly affect E2 activity (Yang et al., 2007). BAY117082, initially described as inhibitor of NF-κB phosphorylation, has been shown to inactivate the E2 conjugating enzymes Ubc13 (UBE2N) and UBCH7 (UBE2L3), as well as the E3 ligase LUBAC (of which HOIP is part) (Strickson et al., 2013). Gliotoxin is a fungal metabolite identified as a selective inhibitor of HOIP through an fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based HTS assay (Sakamoto et al., 2015). Nutlin 3A is a MDM2-p53 interaction inhibitor, able to displace p53 from MDM2 with an IC50 in the 100–300 nM range (Khoury and Domling, 2012). However nutlins are not reported to be able to inhibit MDM2 auto-ubiquitylation. Compound 1 is a pan-inhibitor of ubiquitin-like activating enzymes, an analog of the NEDD8 activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 (Rossi et al., 2014, Soucy et al., 2009). It forms a covalent adduct with the ubiquitin-like substrate through its sulfamate group in a process that requires Mg-ATP. Clomipramine is a compound reported as able to block ITCH ubiquitin transthiolation in an irreversible manner, achieving complete inhibition at 0.8 mM (Rossi et al., 2014). However, in our hands it did not inhibit any of the E3 ligases at 10 μM, and we determined its IC50 for ITCH to be ∼500 μM (Figure S3). We therefore did not follow up clomipramine.

Performing IC50 inhibition curves using the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay (Figure 4; Table S3), we could show that PYR41 inhibited MDM2, ITCH, and HOIP at IC50 values of 3.1, 11.3, and 5.7 μM. BAY117082 also strongly inhibited MDM2 with an IC50 value of 2.4 μM, and HOIP and ITCH with IC50 values of 2.9 and 25.9 μM, respectively. Gliotoxin showed an IC50 value of 2.8 μM against HOIP, of 30.5 μM against ITCH, and 0.5 μM against MDM2. As expected, nutlin-3A did not show any inhibitory activity toward MDM2, ITCH, or HOIP, as it was designed as an interaction inhibitor. We found that Compound 1 inhibited the reactions with all three E3 ligases with similar potencies at 1–2 μM, probably by inhibiting the E1 enzyme. PR619 resulted as the most powerful inhibitor of the ubiquitination cascade, with an IC50 of 0.6 μM against MDM2, 0.4 μM against ITCH, and 0.2 μM when tested against HOIP, suggesting that PR619, which also acts as a DUB inhibitor (Ritorto et al., 2014), has a very low degree of selectivity and inhibits many enzymes with active cysteines.

IC50 determination for six described E3 ligase inhibitors for MDM2 (A), ITCH (B), and HOIP (C). Small inhibitor compounds were pre-incubated for 30 min at different concentrations (0–100 μM). Ubiquitin was added and incubated for a range of time depending on the E3 (usually 30 or 40 min). For statistical analysis, Prism GraphPad software was used with a built-in analysis, nonlinear regression (curve-fit), variable slope (four parameters) curve to determine IC50 values. Data are represented as mean ± SD.

Having established that the E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay can be used to assess the specificity and potency of inhibitors, we explored its suitability for HTS. It is important to underline that, because of the nature of the assay, inhibitors of E1 or E2, which both contain active site cysteines (Rossi et al., 2014, Sakamoto et al., 2015) may be identified as hits. We tested a library of 1,430 FDA-approved compounds from various commercial suppliers with validated biological and pharmacological activities at 10 μM final. None of the compounds present in the library are known for specifically targeting MDM2, ITCH, or HOIP. The assay was performed supplying ATP in excess (1 mM) to reduce the likelihood of identifying ATP analogs as inhibitors of these enzymes.

The screens against the three different E3 ligases, expressed as percentage effect (Figures 5 and S5) exhibited robust Z′ scores >0.5 (Table S5). These scores provide a measure for the suitability of screening assays; HTS assays that provide Z′ scores >0.5 are generally considered robust.

A total of 1,430 compounds from various commercial suppliers were tested at a final concentration of 10 μM each against MDM2, ITCH, and HOIP. The uninhibited control contained 5 nL DMSO but no compound, whereas the inhibited control had been inactivated by pre-treatment with 2.0% TFA.

We defined as a positive hit a compound whose potency ranked above the 50% residual activity threshold. Overall, we identified nine compounds reporting inhibition rates >50% against the E3 ligases of interest. Candesartan cilexetil was the only compound able to inhibit MDM2 activity by more than 50% (see Table 1). With regard to HOIP screening, six compounds were identified as potential inhibitors: bendamustine, moclobemide, ebselen, cefatrizine, fluconazole, and pyrazinamide. The ITCH inhibitor screening identified two positive hits: hexachlorophene and ethacrynic acid. Hexachlorophene is an organochloride compound once widely used as a disinfectant. It acts as an alkylating agent, thus resulting in the wide and not specific inhibition of E3 ligases: this explains why this compound results as a weak inhibitor of MDM2 as well. Ethacrynic acid is a diuretic compound (Melvin et al., 1963) and a potent inhibitor of glutathione S-transferase, with intrinsic chemical reactivity toward sulfhydryl groups (Koechel, 1981), which might explains its ranking as positive hit in our assay when tested against both MDM2 and ITCH. Overall, our results demonstrate that the E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay can be employed to screen large compound libraries against E1, E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases belonging to different families for the identification of new inhibitors in the ubiquitin pathway.

To validate the results obtained from the HTS we performed IC50 determination of compounds with the highest inhibitor potency in the single point screening. Candesartan cilexitel, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, inhibited MDM2 with an IC50 of 8.8 μM (Figure 6A). Best hit was bendamustine, a nitrogen mustard used in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphomas. It belongs to the family of alkylating agents. Bendamustine ranked as the compound with the highest inhibition score against HOIP, while it did not significantly affect MDM2 and ITCH activities. We confirmed that bendamustine selectively inhibited HOIP at an IC50 of 6.4 μM, while ITCH and MDM2 showed a considerably higher IC50 value of 76.8 μM and 114 μM, respectively (Figure 6B). Bendamustine retained its inhibition power when HOIP was paired with UBE2D1 as conjugating enzyme (Figure S6), suggesting that the compound binds preferentially to HOIP. This shows that the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 ligase assay can be used to identify selective inhibitors from a high-throughput screen.

The ubiquitin system has in recent years become an exciting area for drug discovery (Cohen and Tcherpakov, 2010), as multiple enzymatic steps within the ubiquitylation process are druggable. The potential of targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway was first demonstrated in 2003 by the approval of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade; Millennium Pharmaceuticals) for use in multiple myeloma. While proteasome inhibition is a broad intervention affecting general survivability, E3 ubiquitin ligases and DUBs (Ritorto et al., 2014) represent the most specific points of intervention for therapeutic tools as they specifically regulate the ubiquitylation rate of specific substrates. For example, nutlins, cis-imidazoline analogs able to inhibit the interaction between MDM2 and tumor suppressor p53, have recently entered early clinical trials for the treatment of blood cancers (Burgess et al., 2016). The small number of drugs targeting E3 ligases currently on the market is partly due to the lack of suitable high-throughput assays for drug discovery screening. Traditionally, screening for inhibitors of ubiquitin ligases and DUBs has been performed using different fluorescence-based formats in high-throughput and ELISA, SDS-PAGE, and western blotting in low-throughput. These approaches show a number of limitations. ELISA- and SDS-PAGE-based approaches are time consuming and low-throughput by nature, and therefore mostly incompatible with HTS. The applicability of fluorescence-based techniques such as FRET is dependent on being able to get FRET donors and acceptors in the right distance, and the fluorescent label might affect inhibitor binding. To address these issues, we have developed a sensitive and fast assay to quantify in vitro E2/E3 enzyme activity using MALDI-TOF MS. It builds on our DUB MALDI-TOF assay (Ritorto et al., 2014), which has enabled us to screen successfully for a number of selective DUB inhibitors (Kategaya et al., 2017, Magiera et al., 2017, Weisberg et al., 2017), and adds to the increasing number of drug discovery assays utilizing label-free high-throughput MALDI-TOF MS. Apart from E2/E3 enzymes and DUBs (Ritorto et al., 2014), high-throughput MALDI-TOF MS has now successfully been used for drug discovery screening of protein kinases (Heap et al., 2017b), protein phosphatases (Winter et al., 2018), histone demethylases, and acetylcholinesterases (Haslam et al., 2016), as well as histone lysine methyltransferases (Guitot et al., 2014).

In the context of E3 ligase drug discovery, it is critical to identify the appropriate E2/E3 substrate pairing to ensure the development and use of the most physiologically relevant screening assay. There have been many reports of limited E2/E3 activity profiling with a small number of E2 and E3 enzymes using ELISA-based assays, structural-based yeast two-hybrid assays, and western blot (Lechtenberg et al., 2016, Marblestone et al., 2013, Sheng et al., 2012). All of these approaches are time consuming, require large amounts of reagents, and are difficult to adapt for HTS. We have successfully used our E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay to identify active E2/E3 pairings, which could then be further characterized using our HTS screen. The “E2 scan” was quickly and easily adapted, collecting data of three E3 enzymes against 29 E2 enzymes at 8 time points in one single experiment. Moreover, after identification of the right E2/E3 pairs, we applied the MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay to determine inhibition rates and the IC50 values of small-molecule inhibitors. In a proof-of-concept study, we performed an HTS for inhibitors of three E3 ligases. The MALDI-TOF analysis speed of 1.3 s per sample (∼35 min per 1,536-well plate) and low sample volumes (reaction volume 5 μL/MALDI deposition 250 nL) make the E2/E3 MALDI-TOF assay comparable with other fluorescence/chemical probe-based technologies. Automatic sample preparation, MALDI-TOF plate spotting, and data collection allowed us to quickly analyze thousands of compounds through the use of 1,536 sample targets. The assay successfully identified bendamustine as a novel small-molecule inhibitor for HOIP, an attractive drug target for both inflammatory disease and cancer (Ikeda et al., 2011, MacKay et al., 2014, McGuire et al., 2016, Stieglitz et al., 2013). Bendamustine, a nitrogen mustard, shows likely very high reactivity against a range of targets in the cell including its intended target DNA. However, it is surprising that it shows a 12- and 18-fold higher activity against HOIP than against ITCH and MDM2, respectively, suggesting that there is possibly a structural effect and some selectivity can be reached between different E3 ligases. It also shows that E1 conjugating enzymes were not affected by bendamustine as the same enzyme was also used in the MDM and ITCH reaction. While this is just a proof-of-concept study characterizing E2/E3 activity and identifying inhibitors in an in vitro system, follow-up studies will need to verify results in cellular and ultimately in vivo models.

In conclusion, we present here a novel screening method to assay E2/E3 activity with high sensitivity, reproducibility, and reliability, which is able to carry out precise quantified measurements at a rate of ∼1 s per sample spot. Using physiological substrates, we showed proof-of concept for three E3 ligases that are attractive drug targets. Considering the speed, low consumable costs, and the simplicity of the assay, the MALDI-TOF E3 ligase assay will serve as a sensitive and fast tool for screening for E1, E2 enzyme, and E3 ligase inhibitors.

Our understanding of the ubiquitin biology has been rapidly expanding. The role of the ubiquitin system in the pathogenesis of numerous disease states has increased the interest in finding new strategies to pharmacologically interfere with the enzymes responsible of the ubiquitination process. However, the development of molecules targeting the ubiquitin cascade, especially the E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases, has not being extensively sustained by the availability of robust and affordable technologies for extensive primary screening of compound libraries. Performing high-throughput screening in the ubiquitin field remains challenging and it usually requires engineered proteins or the synthesis of chemical probes. Here we show that the MALDI-TOF E2-E3 assay is a robust, scalable, label-free assay that can be employed for primary screening of compound libraries against E2 conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases belonging to different families and representative of all the currently known ubiquitylation mechanisms. The MALDI-TOF E2/E3 assay is a readily accessible addition to the drug discovery toolbox with the potential to accelerate drug discovery efforts in the ubiquitin pathway.

15N-labelled ubiquitin was produced as described in Ritorto et al (Ritorto et al., 2014). Human recombinant 6His-tagged UBE1 was expressed in and purified from Sf21 cells using standard protocols. Human E2s were all expressed as 6His-tagged fusion proteins in BL21 cells and purified via their tags using standard protocols. Briefly, BL21 DE3 codon plus cells were transformed with the appropriate constructs (see table below), colonies were picked for overnight cultures, which were used to inoculate 6 x 1L LB medium supplemented with antibiotics. The cells were grown in Infors incubators, whirling at 200 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.5 – 0.6 and then cooled to 16°C – 20°C. Protein expression was induced with typically 250 μM IPTG and the cells were left over night at the latter temperature. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 4200 rpm for 25min at 4°C in a Beckman J6 centrifuge using a 6 x 1 L bucket rotor (4.2). The cells were resuspended in ice cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.2 % Triton X-100, 10 μg/ml Leupeptin, 1 mM PefaBloc (Roche), 1mM DTT) and sonicated. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 18500 xg for 25 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated for 1 h with Ni-NTA-agarose (Expedeon), then washed five times with 10 volumes of the lysis buffer and then twice in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.015% Brij35, 1 mM DTT. Elution was achieved by incubation with the latter buffer containing 0.4M imidazole or by incubation with Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease (purified in house). The proteins were buffer exchanged into 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT and stored at -80°C. HOIP (697-1072) DU22629 and Itch (DU11097) ligases were expressed in BL21 cells as GST-tagged fusion proteins, purified via their tag and collected by elution (GST-Itch) or by removal of the GST-tag on the resin (HOIP).

pGex-Mdm2 [DU 43570] was expressed in BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells grown in LB media containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Cells were induced with 250 μM isopropyl beta-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD600 of 0.6-0.8 and grown for 16 hours at 15°C. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 1 % Triton, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 % 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM Pefabloc, 1 mM benzamidine. Cell lysis was carried out by sonication. After being clarified through centrifugation, bacterial lysate was incubated with Glutathione Agarose (Expedeon) for 2 hours at 4°C. The resin bound proteins were washed extensively with Wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1 % 2-mercaptoethanol), before being eluted with wash buffer containing 20 mM Glutathione. The purified proteins were dialysed into storage buffer, flash frozen and stored at -80°C.

The E2-E3 reaction consists of recombinant E1 (100 nM), E2 conjugating enzyme (125-250 nM), E3 ligases (250-500 nM) and 0.25 mg/mL BSA in 10 mM HEPES pH 8.5, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM ATP in a total volume of 5 μl. Assays were performed by dispensing 2.5 μL of enzyme solution into round bottom 384-well plates (Greiner, Stonehouse, UK). Plates were centrifuged at 200 xg and the reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 2.5 μL substrate solution containing 10 μM ubiquitin in 5 mM HEPES pH 8.5. For enzyme titration and time course experiments E2/E3 ligases concentrations ranged from 125 nM to 1000 nM with a maximum reaction time of 120 min. Plates were incubated at 37°C for typically 20-60 min (depending on the activity of E3 ligase used) before being quenched by the addition of 2.5 μL of a 10 % (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution. Controls – with only DMSO - where placed on column 23. For the enzyme inactivated controls in columns 24, 2.5 μL of 10 % TFA was manually dispensed prior to addition of the enzyme solution by XRD-384 Automated Reagent Dispenser (FluidX). 1.05 μl of each reaction were spiked with 150 nl (4 μM) of 15N-labelled ubiquitin (average mass 8,659.3 Da) and 1.2 μl of 7.6 mg/ml 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone (DHAP) matrix (prepared in 375 ml ethanol and 125 ml of an aqueous 25 mg/ml diammonium hydrogen citrate).

We used a library of 1430 FDA approved compounds from various commercial suppliers with validated biological and pharmacological activities. For single concentration screening 5 nL of 10 mM compound solution in DMSO was transferred into HiBase Low Binding 384-well flat bottom plates (Greiner bio-one) to give a final screening concentration of 10 μM. Columns 23 and 24 were reserved for uninhibited and inhibited controls respectively. The uninhibited control contained 5 nL DMSO but no compound, whereas the inhibited control contained 5 nL PR-619 but the enzyme was inactivated by pre-treatment with 1.0 % TFA. All compounds and DMSO were dispensed using an Echo acoustic dispenser (Labcyte, Sunnyvale, USA). For all HTS assays the final DMSO concentration was 0.1 %. For concentration response curves of known HOIP, MDM2 and ITCH inhibitors, a threefold serial dilution was prepared from 10 mM compound solutions in DMSO in 384-well base plates V-Bottom (Labtech). 100 nL of compound was transferred into 384-well round bottom low binding plates using a Mosquito Nanoliter pipetter (TTP Labtech, Melbourn, UK), giving a final concentration range between 100 μM and 100 nM.

de Bie P., Ciechanover A. Ubiquitination of E3 ligases: self-regulation of the ubiquitin system via proteolytic and non-proteolytic mechanisms. Cell Death Differ.2011;18:1393–1402. PubMed]

Huang J., Sheung J., Dong G., Coquilla C., Daniel-Issakani S., Payan D.G. High-throughput screening for inhibitors of the e3 ubiquitin ligase APC. Methods Enzymol.2005;399:740–754. [PubMed]

Kenten J.H., Davydov I.V., Safiran Y.J., Stewart D.H., Oberoi P., Biebuyck H.A. Assays for high-throughput screening of E2 AND E3 ubiquitin ligases. Methods Enzymol.2005;399:682–701. [PubMed]

Lechtenberg B.C., Rajput A., Sanishvili R., Dobaczewska M.K., Ware C.F., Mace P.D., Riedl S.J. Structure of a HOIP/E2∼ubiquitin complex reveals RBR E3 ligase mechanism and regulation. Nature.2016;529:546–550. PubMed]

MacKay C., Carroll E., Ibrahim A.F.M., Garg A., Inman G.J., Hay R.T., Alpi A.F. E3 ubiquitin ligase HOIP attenuates apoptotic cell death induced by cisplatin. Cancer Res.2014;74:2246–2257. PubMed]

Marblestone J.G., Butt S., McKelvey D.M., Sterner D.E., Mattern M.R., Nicholson B., Eddins M.J. Comprehensive ubiquitin E2 profiling of ten ubiquitin E3 ligases. Cell Biochem. Biophys.2013;67:161–167. [PubMed]

Marblestone J.G., Larocque J.P., Mattern M.R., Leach C.A. Analysis of ubiquitin E3 ligase activity using selective polyubiquitin binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta.2012;1823:2094–2097. PubMed]

Marblestone J.G., Suresh Kumar K.G., Eddins M.J., Leach C.A., Sterner D.E., Mattern M.R., Nicholson B. Novel approach for characterizing ubiquitin E3 ligase function. J. Biomol. Screen.2010;15:1220–1228. [PubMed]

Rossi M., Rotblat B., Ansell K., Amelio I., Caraglia M., Misso G., Bernassola F., Cavasotto C.N., Knight R.A., Ciechanover A. High throughput screening for inhibitors of the HECT ubiquitin E3 ligase ITCH identifies antidepressant drugs as regulators of autophagy. Cell Death Dis.2014;5:e1203. PubMed]

Sheng Y., Hong J.H., Doherty R., Srikumar T., Shloush J., Avvakumov G.V., Walker J.R., Xue S., Neculai D., Wan J.W. A human ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (E2)-HECT E3 ligase structure-function screen. Mol. Cell Proteomics.2012;11:329–341. PubMed]

The ubiquitylation cascade (Figure 1) requires the action of three enzymes — Ub-activating enzyme (E1), Ub-conjugating enzyme (E2) and Ub protein ligase (E3 ligase) — in an energy-dependent hierarchical cascade [18]. Initially, the C-terminus of Ub is activated by a two-step ATP-dependent reaction in which a thioester bond is formed with a cysteine residue of E1. Ub is subsequently transferred to a cysteine residue of E2 via a thioester transfer reaction. E3s recruit Ub-loaded E2 enzymes and then either directly catalyze the ubiquitylation of the substrate lysine residue or facilitate the transfer of Ub to the substrate from the E2 via HECT (homology to E6-Ap carboxyl terminus), RING (really interesting new gene) or RBR (RING-in-between-RING) domains [19–21]. Recently, the SidE effector protein family of Legionella pneumophila was shown to directly ubiquitylate substrates via an mART motif. This mechanism operates without the need for E1/E2 enzymes or ATP, and activates ubiquitin using nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [22]. Interestingly, the mART motif is also present in a family of mammalian proteins, indicating the potential for this all-in-one enzyme activity to exist in mammals [22]. Ubiquitin-specific proteases (USPs) [also known as deubiquitinases (DUBs)] act as reciprocal regulators of ubiquitlyation by catalyzing the removal of Ub from substrate proteins. Substrate ubiquitylation can signal many cellular fates, depending on chain topology, but one of the best-characterized outcomes is degradation by the proteasome.

One E1 enzyme (UBA1) is encoded in the human genome, with two known isoforms (nuclear and cytoplasmic localizations) [23,24]. Thirty-eight E2s have been identified (reviewed by ref. [25]), and there are ∼100 known DUBs [26]. However, substrate specificity is largely determined by >600 putative E3s identified to date [19,27]. It should be noted that the catalytic activities of many putative E3s and DUBs are yet to be validated. A key feature of the UPS is a significant degree of redundancy and multiplicity, where individual protein substrates may be targeted by multiple E3s (or DUBs), and a single E3 (or DUB) may have multiple protein substrates [28]. An emerging theme in understanding the regulation of protein ubiquitylation comes from the observation that E3/DUB pairs can act in a highly co-ordinated manner to regulate ubiquitylation (and hence activity) of each other and downstream substrates, although only a few examples have been observed to date [29–31]. The E3 ligase:DUB pair of Rsp5:Ubp2 acts in a co-ordinated fashion, with Ubp2 antagonizing Rsp5 E3 ligase activity by forming a complex together with Rsp5 and Rup1 that deubiquitylates Rsp5 substrates [29]. The DUB USP9X has been shown to stabilize the E3 ligase SMURF1 in MDA-MB-231 cells [31], and another interesting example is the reciprocal regulation of abundance and activity of the E3 ligase:DUB pair of UBR5 and DUBA, which controls IL-17 production in T cells. UBR5 destabilizes DUBA through ubiquitylation, whereas DUBA stabilizes UBR5 in activated T cells by attenuating degradative auto-ubiquitylation, triggering UBR5-mediated ubiquitylation of the transcription factor RORyt in response to TGF-β [30].

Most components of the UPS — from E1 through to the proteasome — are under active investigation as potential therapeutic targets in cancer and other indications [32–35]. The best-known compound targeting the UPS is the dipeptide boronic bortezomib (velcade) [36,37], a 26S proteasome inhibitor approved for clinical use in multiple myeloma [38]. Thalidomide and its analogues (lenalidomide-CC-5013 and pomalidomide-CC-4047) are immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) approved for clinical use in the treatment of multiple myeloma (reviewed in ref. [39]). Although the precise molecular mechanism remains unclear, IMiDs are thought to exert their teratogenic and anti-tumour effects by targeting cereblon (CRBN) [40]. The interaction disrupts the function of the E3 ligase complex constituted by CRBN, DDB1 and Cul4, causing down-regulation of fibroblast growth factor genes [40,41]. Apcin (APC inhibitor) is a novel small molecule inhibitor of another E3 ligase complex: anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) [42]. Apcin binds to and competively inhibits Cdc20, a substrate recognition co-receptor of APC/C [42]. This effect is amplified by the co-addition of another small molecule inhibitor — tosyl-l-argine methyl ester — which also blocks the APC/C–Cdc20 interaction [42].

Several studies have shown that ubiquitin variants (UbVs) can also function as highly specific inhibitors or activators for various enzymes, including E3s and DUBs. For example, UbVs have been developed to either inhibit HECT E3s by binding to the E2-binding site or activate by targeting an ubiquitin-binding exosite [44]. Furthermore, exploitation of the low-affinity interactions between Ub and enzymes of the ubiquitin system by engineered optimization has produced potent and selective modulators of UPS components, including DUBs, E2s and E3s [45]. These UbVs will be very useful tools to elucidate the function of E3s by modulating their activity.

As E3 ligases primarily determine the substrate specificity of the UPS they may represent more specific targets for inhibition [46,47]. The pursuit of inhibitors that target specific E3 ligase activity or block E3–substrate interactions led to the development of Nutlins (cis-imidazoline compounds), which are currently in clinical trials for various indications. Nutlins prevent binding of the E3 ligase MDM2 to its substrate, the tumour suppressor p53 [19,48–51]. Another compound currently in clinical trials for cancer is the Smac mimetic GDC-0152, which binds to anti-apoptotic proteins (IAPs), inducing IAP self-ubiquitylation and degradation, and consequently apoptosis [52].

Although E3 ligases make promising therapeutic targets, efforts into developing therapeutics targeting E3 ligases have so far been relatively ineffective — with no drugs currently approved for clinical use. This is partly due to limited understanding of ligase–substrate relationships and biological function. A key to the development of effective therapeutics is the identification of E3 ligase substrates and, conversely, the ligases are targeting a specific substrate. These will not only advance understanding of functional roles but also are necessary for the development of functional assays for drug screening and associated discovery and the validation of relevant biomarkers.

You can cancel your subscription at any time. For annual commitment subscriptions, such as Office 365 E3, there is a penalty for canceling before the end of your contract. Read the complete

Yes, you can mix and match Office 365 plans. Please note that there are some license limitations at the plan level. The Microsoft 365 Apps for business, Microsoft 365 Business Basic, and Microsoft 365 Business Standard plans each have a limit of 300 users, while the Enterprise plans are for an unlimited number of users. For example, you can purchase 300 Microsoft 365 Business Standard seats, 300 Microsoft 365 Business Basic seats, and 500 Enterprise E3 seats on a single tenant.

Many Office 365 plans also include the desktop version of Office, for example, Microsoft 365 Business Standard and Office 365 E3. One of the benefits of having the desktop version of Office applications is that you can work offline and have the confidence that the next time you connect to the Internet all your work will automatically sync, so you never have to worry about your documents being up to date. Your desktop version of Office is also automatically kept up to date and upgraded when you connect to the Internet, so you always have the latest tools to help you work.

In general, top-of-the-line displays, that are priced significantly higher than traditional devices, have Delta E levels of one or less. It’s impossible to get down to zero, however. Next to that, however, are the high-end, high-quality devices that have a Delta E of ≦2.

The precision provided by CIELAB is at a level where it requires significantly more data per pixel, compared to RGB and CMYK standards. Since the gamut of the standard is higher than most computer displays, occasionally there is some loss of precision; however, advances in technology have made such issues negligible.

Many displays are comprised of red, green, and blue lights. When seen from afar, usually two feet or further, then the colors merge. When examined closely, the human eye is able to see different sources.

Regardless of the color space you use for your projects or displays, be it CIELAB, RGB, or HSV; you’ll always want to consider the Delta E levels of your equipmen

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey