display screens disrupt sllep in stock

Joanna Cooper, M.D., a neurologist and sleep medicine specialist with the Sutter East Bay Medical Foundation, says bright screens stimulate the part of our brain designed to keep us awake. Looking at a brightly-lit screen prior to sleep can make for a restless night.

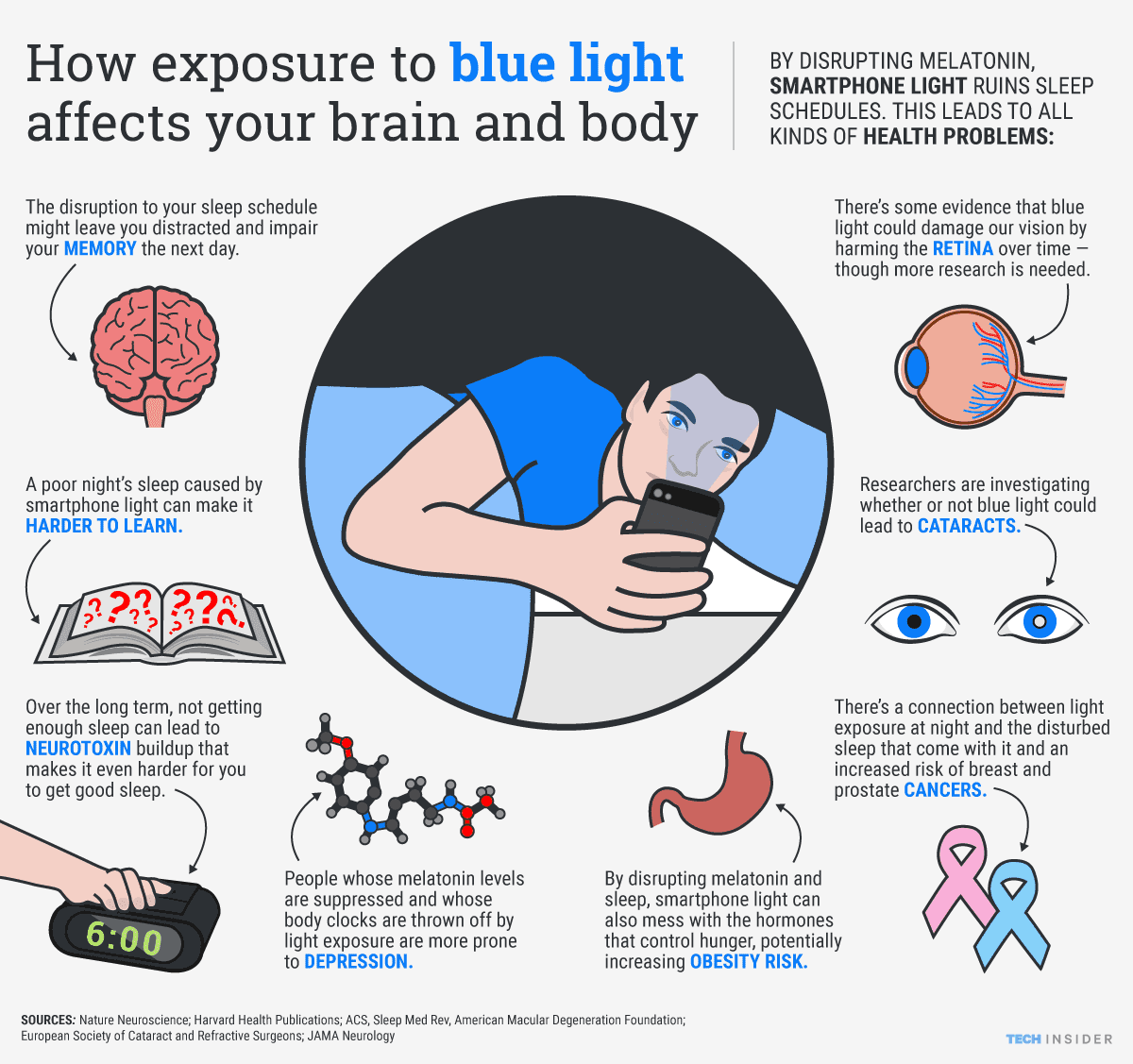

Device screens produce blue light, Dr. Cooper says, which is the part of the light spectrum most active in our sleep cycle. Stimulation of this part of the brain suppresses production of melatonin, making it difficult for many people to “turn off” their brains and fall asleep.

“The light from our screens can delay our transition to sleep, even if we are engaged in some soothing activity online,” Dr. Cooper says. “But it’s more likely that our evening texting, television shows or video games are stimulating in themselves, keeping the brain busy and wound up, and even causing adrenaline rushes instead of calm.”

See Full Reference to sleep problems stemming from electronic devices that emit blue light. Numerous studies have established a link between using devices with screens before bed and increases in sleep latency, or the amount of time it takes someone to fall asleep. Additionally, children who use these devices at night often do not receive enough high-quality sleep and are more likely to feel tired the next day.

See Full Reference. Unlike blue light, red, yellow, and orange light have little to no effect on your circadian rhythm. Dim light with one of these colors is considered optimal for nighttime reading. Portable e-readers like the Kindle and Nook emit blue light, but not to the same extent as other electronic devices. If you prefer to use an e-reader such as a Kindle or Nook, dim the display as much as possible.

Establish a Relaxing Bedtime Routine: A regular bedtime that ensures an adequate amount of rest is essential for healthy sleep. The hour before bed should consist of relaxing activities that don’t involve devices with screens.

See Full Reference reduce blue light emissions and decrease the display’s brightness setting. You should manually dim the display if your device does not automatically adjust the brightness in nighttime mode.

Here are ways you can reduce the negative effects of screen time on your child’s sleep:Avoid digital technology use in the hour before bedtime. This includes mobile phones, tablets, computer screens and TV. Encourage reading or quiet play instead.

Computers, televisions, tablets and other electronic devices give off all colors of light. And, he notes, evidence has been emerging that these screens — and especially the blue light they give off — can disrupt the body’s clock. Data show that this blue light tends to make us more alert at night. That makes it harder to fall asleep get all the rest we need.

Because electronic devices are all around us, it’s hard to avoid their blue light. We use the screens constantly, notes Amit Shai Green. He is a PhD student at the University of Haifa in Israel. He also is an author of the new study.

The researchers had tweaked the computer screens. Some gave off intense blue light. Others gave off soft blue light, intense red light or soft red light. Red light hasn’t been shown to affect sleep the way blue light does. For the new experiment, the researchers used red light as a control against which to compare any effects on sleep of blue light.

Looking at screens that gave off intense blue light cut someone’s sleep by about 16 minutes, compared to when they had used screens with red light. Those exposed to blue light also woke up more often at night than if they had been exposed to red light.

Using screens before bed damages the body’s biological clock, Green says. More and more people are using screens as kids and adolescents. At this age, their brains are still developing the ability to learn and pay attention. That makes the new results worrisome, Green says.

Rahman says the new work makes a good point about how blue light from screens can be bad for our bodies. However, he points out, the light in this study was extremely bright. It was far more bright than what a normal computer, tablet or TV would emit. Also, the screens were about 22 inches (about 56 centimeters) across. Tablets and phones are much smaller. So it’s hard to say how their blue light impacts on sleep might compare to those from using a device as large as the ones in this study.

Still, Rahman says the results remind us to think about how we use screens before bed. He recommends powering down electronics two hours before going to sleep. Read a book instead, he says. Talk with your family and friends. Write in a journal.

Technology helps facilitate education, communication, and entertainment, and technological devices have become a crucial element of navigating daily life. However, some devices may interrupt or negatively impact sleeping patterns. These include laptops, tablets, smartphones, and televisions – all of which feature screens that emit blue light. Overexposure to blue light in the evening can make it more difficult to fall and remain asleep.

Many electronic devices come equipped with “nighttime modes”, which can be activated to project less light from their screens. Nighttime modes may not be effective for improving sleep on their own. For example, one study focused on the Night Shift mode for iPad tablets. Researchers found that using Night Shift mode and adjusting the device’s brightness settings are both needed to reduce melatonin suppression for nighttime users.

Sleep is a critical aspect of health. One study found that children who watched more television, used a computer, played video games, or used their cell phones before bedtime not only experienced disruptions to sleep quality and quantity, but were also more likely to be overweight. These children were also more likely to feel tired in the morning and skip breakfast, a habit that has been linked to weight gain. Obesity can increase the likelihood of experiencing obstructive sleep apnea, which disrupts sleep and can lead to morning headaches.

Experts recommend that children and teens keep screens out of the bedroom and aim to stop using electronic devices at least 30 to 60 minutes before bed. These recommendations are a good place to start for adults as well.

For some, eliminating screens from the bedroom may not be possible due to work or family commitments. However, it is important to set a distinct time between device use and sleep. If you do keep your device in your room, consider turning off lights and silencing notifications.

Parents, educators, and clinicians express concern about whether excessive use of screen media among young people affects sleep and wellbeing. In this article, we provide an overview of the current science on screens and sleep, with a focus on recommendations to reduce the potentially problematic influence of screen time on pediatric sleep. We then review how impaired sleep in pediatric populations may lead to a range of adverse behaviors, physical health problems and well-being outcomes. We begin with a summary of the two consensus statements on child and adolescent sleep needs. Then we summarize the range of screen habits among youth, focusing on screen habits at bedtime. Next, we review current literature on evidence of the effects of youth screen habits on sleep, and the mechanisms by which screen habits may impact sleep. We conclude with evidence-based strategies to improve sleep through sleep-friendly screen-behavior recommendations and other take-home messages for families and practitioners.

Exposure to the light emitted by screens in the evening hours before and/or during bedtime is another likely mechanism by which use of screen media negatively impacts sleep. Screen-based light may affect sleep via several pathways:increasing arousal and reducing sleepiness at bedtime,

Clinicians can help families improve their sleep health and screen media habits by encouraging parenting marked by high levels of warmth and support, as well as limits that are clearly communicated, consistently applied appropriate to the child’s behavior and context, and allow for developmentally appropriate autonomy(i.e. an authoritative parenting style). Box 1) All parents should begin instilling family bedtime routines and healthy sleep habits early in life, and adjust these routines as youth mature (See Box 2). If the youth health behaviors and habits become part of the child’s own daily routine, she will be better able to take charge of her own sleep health behaviors when this becomes appropriate in later years. For younger children, these routines mean establishing household rules related to screens and sleep early on. For older children and adolescents, they involve open conversation about the core reasons for behaviors. This proactive and engaged parenting style promotes cooperation and parent-child shared goals for children’s health and well-being, and aims to help children develop self-regulation skills, and eventually increasing autonomy to govern their own behavior.

For teenagers presenting with excessive screen time, a few clinical pearls may help families to follow the recommendations laid out in Box 1 and 2, below. First, one must always focus on the chief complaint, what brought the patient to seek help in the first place. In cases of excessive nighttime screen media use, children and adolescents are often seen in the clinician’s office for poor academic performance or lack of concentration in school. Upon taking a careful history, the clinician often discovers a significant lack of sleep, often attributable to patients staying up late while using mobile devices, computers, or videogames. Clinicians must discover the underlying factors (e.g., social or family stress) which drive the patient to use the screens in the late hours. Addressing such factors directly may be essential to motivating families to achieve healthier screen habits.

The currently-supported mechanisms underlying the relationship between screen media habits and sleep outcomes include (1) displacement of time spent sleeping by time spent using screens, (2) psychological stimulation from screen-media content, and (3) alerting and circadian effects of exposure to light from screens.

6. Falbe J, et al. Sleep duration, restfulness, and screens in the sleep environment. Pediatrics.2015;135:e367–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2306. PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Chaput JP, et al. Electronic screens in children’s bedrooms and adiposity, physical activity and sleep: do the number and type of electronic devices matter? Can J Public Health.2014;105:e273–279. PubMed]

61. Higuchi S, Motohashi Y, Liu Y, Maeda A. Effects of playing a computer game using a bright display on presleep physiological variables, sleep latency, slow wave sleep and REM sleep. J Sleep Res.2005;14:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00463.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Higuchi S, Motohashi Y, Liu Y, Ahara M, Kaneko Y. Effects of VDT tasks with a bright display at night on melatonin, core temperature, heart rate, and sleepiness. J Appl Physiol (1985)2003;94:1773–1776. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2002. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

In a world increasingly dependent on technology, bright screens are more commonly part of our everyday life. These screens range broadly in size and purpose: televisions, computers, tablets, smartphones, e-books, and even wearable tech.

The Source of Light:Artificial light can come from light bulbs and many other sources, including the screens of televisions, computers, tablets, smartphones, e-books, and even wearable tech. Each of these can generate different amounts of light that can impact our sleep.

The Amount of Light:Each source of light generates its own light intensity. For comparison, full sunlight at midday may be 100,000 lux, whereas commercially available light boxes that are used to treat seasonal affective disorder often generate about 10,000 lux, and the screen of your smartphone may create hundreds of lux of light intensity, depending on the settings you use. (A unit of lux describes how much light falls on a certain area; whereas a unit of lumens tells you the total amount of light emitted by the light source). Using lux helps us understand how nearby screens may have more impact on us than the same screen from across a room. Even smaller amounts of light, such as from a smart phone that is held 12 inches from our face before going to sleep, may have a negative impact on our sleep.

The Color of Light: Much is made of the fact that blue light is responsible for shifting circadian rhythms, while red, yellow, and orange light waves do not have this effect. Full-spectrum light, what you might consider as “white light” or “natural light,” contains the blue wavelengths as well. Digital screen filters, blue light blocking glasses, and prescription glasses with FL-41 tint are sold to block this blue light wavelength to minimize disruption to our circadian rhythms.

"We are continuously exposed to artificial light, whether from screen time, spending the day indoors or staying awake late at night," says Salk Professor Satchin Panda, senior author of the study. "This lifestyle causes disruptions to our circadian rhythms and has deleterious consequences on health."

If you have trouble sleeping, laptop or tablet use at bedtime might be to blame, new research suggests. Mariana Figueiro of the Lighting Research Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and her team showed that two hours of iPad use at maximum brightness was enough to suppress people"s normal nighttime release of melatonin, a key hormone in the body"s clock, or circadian system. Melatonin tells your body that it is night, helping to make you sleepy. If you delay that signal, Figueiro says, you could delay sleep. Other research indicates that “if you do that chronically, for many years, it can lead to disruption of the circadian system,” sometimes with serious health consequences, she explains.

The dose of light is important, Figueiro says; the brightness and exposure time, as well as the wavelength, determine whether it affects melatonin. Light in the blue-and-white range emitted by today"s tablets can do the trick—as can laptops and desktop computers, which emit even more of the disrupting light but are usually positioned farther from the eyes, which ameliorates the light"s effects. The team designed light-detector goggles and had subjects wear them during late-evening tablet use. The light dose measurements from the goggles correlated with hampered melatonin production.

On the bright side, a morning shot of screen time could be used as light therapy for seasonal affective disorder and other light-based problems. Figueiro hopes manufacturers will “get creative” with tomorrow"s tablets, making them more “circadian friendly,” perhaps even switching to white text on a black screen at night to minimize the light dose. Until then, do your sleep schedule a favor and turn down the brightness of your glowing screens before bed—or switch back to good old-fashioned books.

Technology helps facilitate education, communication, and entertainment, and technological devices have become a crucial element of navigating daily life. However, some devices may interrupt or negatively impact sleeping patterns. These include laptops, tablets, smartphones, and televisions – all of which feature screens that emit blue light. Overexposure to blue light in the evening can make it more difficult to fall and remain asleep.

Many electronic devices come equipped with “nighttime modes”, which can be activated to project less light from their screens. Nighttime modes may not be effective for improving sleep on their own. For example, one study focused on the Night Shift mode for iPad tablets. Researchers found that using Night Shift mode and adjusting the device’s brightness settings are both needed to reduce melatonin suppression for nighttime users.

Sleep is a critical aspect of health. One study found that children who watched more television, used a computer, played video games, or used their cell phones before bedtime not only experienced disruptions to sleep quality and quantity, but were also more likely to be overweight. These children were also more likely to feel tired in the morning and skip breakfast, a habit that has been linked to weight gain. Obesity can increase the likelihood of experiencing obstructive sleep apnea, which disrupts sleep and can lead to morning headaches.

Experts recommend that children and teens keep screens out of the bedroom and aim to stop using electronic devices at least 30 to 60 minutes before bed. These recommendations are a good place to start for adults as well.

For some, eliminating screens from the bedroom may not be possible due to work or family commitments. However, it is important to set a distinct time between device use and sleep. If you do keep your device in your room, consider turning off lights and silencing notifications.

"We are continuously exposed to artificial light, whether from screen time, spending the day indoors or staying awake late at night," says Salk Professor Satchin Panda, senior author of the study. "This lifestyle causes disruptions to our circadian rhythms and has deleterious consequences on health."

With their brains, sleep patterns and even eyes still developing, children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the sleep-disrupting effects of screen time, according to a sweeping review of the literature published today in the journal Pediatrics.

“The vast majority of studies find that kids and teens who consume more screen-based media are more likely to experience sleep disruption,” says first author Monique LeBourgeois, an associate professor in the Department of Integrative Physiology at CU Boulder. “With this paper, we wanted to go one step further by reviewing the studies that also point to the reasons whydigital media adversely affects sleep.”

Through the young eyes of a child, exposure to a bright blue screen in the hours before bedtime is the perfect storm for both sleep and circadian disruption,” LeBourgeois says.

“The digital media landscape is evolving so quickly, we need our research to catch up just to answer some basic questions,” says Dr. Pam Hurst-Della Pietra, founder of the nonprofit Children and Screens, which helped orchestrate the issue.

“It’s not how long we’re using screens that really matters; it’s how we’re using them and what’s happening in our brains in response,” says Rich, director of the Center on Media and Child Health at Boston Children’s Hospital, associate professor of pediatrics at HMS, and associate professor of social and behavioral sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

A good night’s sleep is also key to brain development, and HMS researchers have shown that using blue light-emitting screen devices like smartphones before bedtime can disrupt sleep patterns by suppressing secretion of the hormone melatonin.

He and his team plan to discover targets for treatments that will counter circadian rhythm disruption, which can result, for example, from artificial light exposure.

Using blue-light devices suppresses the secretion of melatonin, a hormone released from the pineal gland overnight to control your sleep-wake schedule. As a result, it takes your body much longer to feel tired and delays bedtime significantly. Screens also stimulate parts of the brain that make us feel alert, raise our body temperature and heart rates. This makes it difficult to stay asleep and feel well-rested.

These results are fairly alarming, as it shows that the screens we so often use nowadays are having a negative impact on our sleep time and quality of sleep. Charles Czeisler, PhD, MD, FRCP, and chief of Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders notes that there has been a decline in average sleep duration and quality in the past 50 years, and attributes this decline directly to electronic devices emitting blue light. Below is a chart that shows the decline in average hours of sleep over the years.

Screens are now a fixture of modern childhood. As young people spend an increasing amount of time on electronic devices, the effects of these digital activities has become a prevalent concern among parents, caregivers, and policy-makers. Research indicating that between 50% to 90% of school-age children might not be getting enough sleep has prompted calls that technology use may be to blame. However, the new research findings from the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, has shown that screen time has very little practical effect on children’s sleep.

In practical terms, while the correlation between screen time and sleep in children exists, it might be too small to make a significant difference to a child’s sleep. For example, when you compare the average nightly sleep of a tech-abstaining teenager (at 8 hours, 51 minutes) with a teenager who devotes 8 hours a day to screens (at 8 hours, 21 minutes), the difference is overall inconsequential. Other known factors, such as early starts to the school day, have a larger effect on childhood sleep.

"This suggests we need to look at other variables when it comes to children and their sleep," says Przybylski. Analysis in the study indicated that variables within the family and household were significantly associated with both screen use and sleep outcomes. "Focusing on bedtime routines and regular patterns of sleep, such as consistent wake-up times, are much more effective strategies for helping young people sleep than thinking screens themselves play a significant role."

The aim of this study was to provide parents and practitioners with a realistic foundation for looking at screen versus the impact of other interventions on sleep. "While a relationship between screens and sleep is there, we need to look at research from the lens of what is practically significant," says Przybylski. "Because the effects of screens are so modest, it is possible that many studies with smaller sample sizes could be false positives - results that support an effect that in reality does not exist."

"The next step from here is research on the precise mechanisms that link digital screens to sleep. Though technologies and tools relating to so-called ‘blue light’ have been implicated in sleep problems, it is not clear whether play a significant causal role," says Przybylski. "Screens are here to stay, so transparent, reproducible, and robust research is needed to figure out how tech affects us and how we best intervene to limit its negative effects."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1363458925-3b3ae6e04ba84b1e801d29dc533c9603.jpg)

Joanna Cooper, M.D., a neurologist and sleep medicine specialist with the Sutter East Bay Medical Foundation, says bright screens stimulate the part of our brain designed to keep us awake. Looking at a brightly-lit screen prior to sleep can make for a restless night.

Device screens produce blue light, Dr. Cooper says, which is the part of the light spectrum most active in our sleep cycle. Stimulation of this part of the brain suppresses production of melatonin, making it difficult for many people to “turn off” their brains and fall asleep.

“The light from our screens can delay our transition to sleep, even if we are engaged in some soothing activity online,” Dr. Cooper says. “But it’s more likely that our evening texting, television shows or video games are stimulating in themselves, keeping the brain busy and wound up, and even causing adrenaline rushes instead of calm.”

Most of us view some type of electronic device for many hours each day. This includes TVs, smartphones, tablets, and gaming systems. But how does the blue light from those screens affect our health?

About one-third of all visible light is considered blue light. Sunlight is the biggest source of blue light. Artificial sources of blue light include fluorescent light, LED TVs, computer monitors, smartphones, and tablet screens.

Blue light exposure from screens is small compared to the amount of exposure from the sun. However, there is concern about long-term effects of screen exposure from digital devices. This is especially true when it comes to too much screen time and screens too close to the eyes.

Exposure to blue light before bedtime also can disrupt sleep patterns as it affects when our bodies create melatonin. Interruption of the circadian system plays a role in the development of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, sleep disorders, and cognitive dysfunctions.

Get blue-light filters for your smartphone, tablet, and computer screen. The filters prevent much of blue light from reaching your eyes without affecting the visibility of the display.

However, it’s not just that you’re on your phone that can disrupt your sleep. It’s more what you’re doing with the technology that makes a difference, like actively using your phone.

Phone screens and sleep have a tricky relationship. The blue light from your phone is an artificial color that mimics daylight. This can be great during the day, as it can make you feel more alert, but it’s just the opposite of what you need at night when you’re winding down and ready to hit the hay.

This isn’t necessarily happening to everyone, though. “Studies that have really shown support for light’s impact on sleep onset and melatonin production are much more people using screens for two hours straight prior to bedtime,” Dr. Drerup notes.

Dr. Drerup adds that what you’re doing on your phone before bed matters more. “The content you’re looking at probably has more of an impact than the blue light from the screens,” says Dr. Drerup. “There might be people that are more sensitive to it — but it’s really much more about what you’re doing on those devices.”

You probably know what it’s like to scroll through Facebook right before bed and see something that makes you upset. Unsurprisingly, stress and anxiety are often two major reasons for disrupted sleep.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey