oxide tft lcd supplier

LG Display"s oxide TFT technology can be applied to various display products. Since its performance is more than 50 times higher than that of the existing a-Si TFT, it can be applied to the entire product lines from mobiles to laptops and large TVs.

By reducing the size of the TFTs that make up individual pixels and increasing their performance, a display with high resolution and rich colors can be achieved.

By applying oxide TFT, the size of the circuit part of the panel outside the screen can be drastically reduced, making it possible to create a slim design display.

Oxide TFT is highly energy-efficient because the leakage current is very small when the screen is not working, so it can extend the battery life of notebooks or tablets.

LG Display is a pioneer in the industry"s first successful mass-production by researching and developing oxide TFT technology for the longest period of time. LG Display guarantees product reliability that customers can trust and use for a long time.

in-TOUCH products with built-in touch function can maintain slim design and superior image quality compared to add-on (out-cell) touch products with added touch electrodes. It is a technology unique to LG Display that can be applied not only in IT but also in various fields such as home application, health, industrial, and medical products. in-Touch has a built-in touch electrode in the LCD, optimized for slim & light products that can perform touch operation without additional touch electrodes or cover glass.

Oxide thin-film transistor (TFT) liquid crystal display (LCD) panels are increasingly adopted in mobile PCs due to their feature of high resolution while consuming low power. Global shipments of large oxide TFT LCD panels of 9 inches or larger are expected to grow from 20 million units in 2016 to 55.6 million units in 2017, according to new analysis from IHS Markit (Nasdaq: INFO). Of those, 51 million units are estimated to be applied to mobile PCs, which include notebook PCs and tablet PCs, up 200 percent from 17 million units in 2016.

“Demand for high-resolution panels has increased as media content for mobile PCs became available in higher resolutions,” said David Hsieh, senior director at IHS Markit. “Apple’ and Microsoft’s use of oxide TFT LCD panels for products – iPad, iPad Pro, and Surface, respectively – helped increase the oxide mobile PC panel market and encouraged other PC brands to follow suit.”

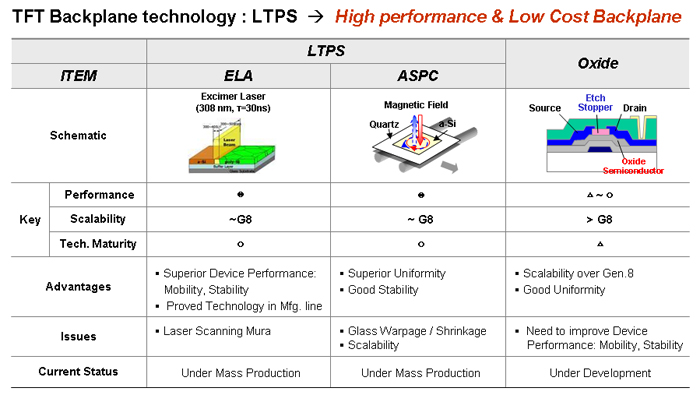

Low-temperature polysilicon (LTPS) and oxide TFT LCD solutions are major candidates for displaying high-resolution images, and they are expected to account for more than 19 percent of the entire mobile PC display market in 2017, according to the Large Area Display Market Tracker by IHS Markit.

While LTPS can deliver higher resolution images and consume less power than oxide TFT LCD or a-Si TFT LCD, it has its own limits: its production cost is high and the yield rate is low. In addition, it is less efficient to produce large panels. Albeit not as high resolution as LTPS, oxide TFT LCD panels still display high-resolution images better than the a-Si solution, and they are suitable to produce large panels at lower production cost than LTPS.

LG Display and Sharp have expanded their oxide mobile PC panel shipments aggressively by 180 percent and 370 percent, respectively. CEC Panda in China is estimated to increase its shipments from about 600,000 units in 2016 to 4.2 million in 2017. As some oxide panel suppliers are reducing their focus on the mobile PC display business, display makers in China and Taiwan, such as BOE and Innolux, are expected to produce more oxide panels in future, IHS Markit said.

The statistic illustrates large oxide TFT LCD panel unit shipments in 2016 and 2017, by type. Large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments for tablet PCs are projected to reach 32.6 million units worldwide in 2017.Read moreGlobal large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments by type in 2016 and 2017 (in million units)*CharacteristicTVTablet PCNotebook PCMonitor-----

IHS. (November 6, 2017). Global large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments by type in 2016 and 2017 (in million units)* [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved December 28, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/784229/global-large-oxide-tft-lcd-panel-shipment-by-type/

IHS. "Global large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments by type in 2016 and 2017 (in million units)*." Chart. November 6, 2017. Statista. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/784229/global-large-oxide-tft-lcd-panel-shipment-by-type/

IHS. (2017). Global large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments by type in 2016 and 2017 (in million units)*. Statista. Statista Inc.. Accessed: December 28, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/784229/global-large-oxide-tft-lcd-panel-shipment-by-type/

IHS. "Global Large Oxide Tft Lcd Panel Shipments by Type in 2016 and 2017 (in Million Units)*." Statista, Statista Inc., 6 Nov 2017, https://www.statista.com/statistics/784229/global-large-oxide-tft-lcd-panel-shipment-by-type/

IHS, Global large oxide TFT LCD panel shipments by type in 2016 and 2017 (in million units)* Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/784229/global-large-oxide-tft-lcd-panel-shipment-by-type/ (last visited December 28, 2022)

4.5.Comparing the key attributes of different TFT technologies (a-Si, pc-Si, nc-Si, OTFT, graphene, CNT, etc). Parameters include manufacturing technique, mobility, uniformity, stability, and commercialisation stage and primary uses

7.1.Radar chart assessing the merits of different backplane technologies (LTPS, oxide, a-Si, organics) for LCD displays. The parameters considered are resolution, size, flexibility, on-pixel processing, and 3D. Here, the scale is from

7.2.Radar chart assessing the merits of different backplane technologies (LTPS, oxide, a-Si, organics) for OLED displays. The parameters considered are resolution, size, flexibility, on-pixel processing, and 3D. Here, the scale is fro

7.7.Announced annual production capacity (area) of various OLED display manufactures in 2015-2016. Two categories are developed: 1) LTPS backplanes and 2) oxide backplanes

The display industry is continuing to move toward mid-to-large-size, immersive displays in high-performance tablets, notebooks and 8K TVs. As these trends become industry standards, the oxide market emerges as an important opportunity for enabling the next-generation of high-performance displays. These displays feature: higher resolution and faster refresh rates; enhanced circuitry integration to achieve slim bezels; and cost savings for panel makers by improving the panel aperture ratio and enabling large gen size manufacturing.

To achieve these technical requirements, new breakthroughs are needed in thin-film-transistor (TFT) technologies. Among the display industry’s current offerings, amorphous silicon TFT (a-Si TFT) maintains a leading position among all applications, while low-temperature poly-silicon TFT (LTPS) is the predominant display technology for enabling high-performance handheld displays. The key differences between a-Si and LTPS are that an a-Si TFT has a simpler process, structure, and is easier to scale up in terms of manufacturing. However, LTPS offers better TFT performance to achieve higher resolutions and lower power consumption. The drawbacks of LTPS come in size limitations and increased manufacturing costs. For these reasons, neither a-Si or LTPS can fully meet the technical requirements for this next generation of high-performance displays.

All of these industry requirements create new process and glass composition challenges, which present the need to develop an advanced oxide TFT glass technology.

For decades, the dominant technology for flat panel displays was an amorphous silicon (a-Si) backplane. The vast majority of displays were made using a-Si backplanes due to the simplicity in manufacturing process, good economics, and scalability to larger sizes. As demands for brighter and/or higher resolution displays grew due to the introduction and proliferation of handheld mobile devices, alternative backplane technologies, such as low temperature polysilicon (LTPS), became more prevalent. LTPS is similar to a-Si, but requires higher processing temperatures and a more complicated manufacturing process. This results in advanced properties for the backplane, such as >50X higher electronic mobility. These properties allow smaller TFTs (enabling higher resolutions and brighter displays) and faster refresh rates. While clearly a superior technology to a-Si, the higher temperatures and more complex manufacturing process make LTPS considerably more expensive than a-Si. Additionally, LTPS is not easily scaled to larger sizes to enable better panel economics.

The ideal backplane technology would combine the simplicity, economics, and scalability to larger panel sizes of a-Si with the heightened performance of LTPS. This is exactly what oxide TFT technologies offer. The most commonly implemented oxide TFT technology is based on Indium-Gallium-Zinc-Oxide or “IGZO” technologies.

Though the mobility of oxide TFT is not as high as LTPS, it is an order of magnitude better than a-Si technology and capable of driving OLED displays and 8K 120Hz + LCD TVs. Additionally, the low off-current of an oxide TFT could enable low refresh frequency without flicker effects on static images (a comparison of different TFT technologies are shown in Table 1). While, like LTPS, oxide TFT backplanes have improved electrical properties relative to a-Si backplanes, oxide TFT backplanes can scale up to Gen 10.5 at reasonable costs (unlike LTPS), thereby enabling high-end, large-size LCD and OLED TVs. It is for this “just right” compromise of a-Si and LTPS properties that oxide TFT is garnering so much attention from panel makers worldwide. It offers the ability to manufacture displays far superior to a-Si at sizes and costs unachievable by LTPS.

There are two major oxide TFT processes to consider: etch-stop and back channel etch (BCE). The key difference between the processes is the use of an etch-stop layer, also known as ESL, that is required to protect the IGZO channels during the etching process.

Oxide TFT reliability was the major concern in early stage of oxide TFT development. The oxide TFT channel was usually damaged in subsequent processes, so an etch stop structure was designed to protect the oxide TFT channel. The etch-stop (ESL) oxide TFT manufacturing process begins with a bottom gate structure which is covered by a gate insulator and TFT islands. After the gate insulator (GI) layers and TFT patterning, a patterned SiO2 layer is deposited to cover the IGZO channel area in order to protect oxide TFT from following source/drain (S/D) etching. This enables better TFT reliability, and after the S/D etching, then followed by passivation, ITO layer as the Figure 1 shows. In the ESL process, temperatures may go up to 300-400°C for up to an hour or more. While these are higher temperatures than some a-Si processes, it is considerably lower than the typical LTPS processes that can exceed 500°C.

The BCE oxide TFT process (Figure 2) is very similar to the ESL oxide TFT process in the first two photo etching processes (PEP) steps. However, a high temperature (400-500°C) annealing process enhances the TFT reliability that allows the removal of the ESL. The higher temperature annealing step requires a thermally stable glass that can withstand harsh manufacturing environments and processing times relative to the conventional oxide (ESL) or a-Si processes.

To panel makers, the BCE oxide TFT process is similar to the a-Si process, which has been widely used for the past two decades. Also, there is one photo-mask process reduction compared to the ES oxide TFT process, therefore, BCE oxide TFT is becoming a mainstream process of oxide TFT manufacturing.

While the oxide TFT process has clear technical benefits for the manufacture of large and high-performance TVs, it presents a unique set of challenges for the glass substrate used in the process.

When put through a typical TFT backplane process, glass substrates will change shape or size (i.e., strain) which is called a change in total pitch (TP). One of the most important glass substrate attributes is total pitch variation (TPV), which is the deviation from predictable glass movement within a glass sheet and from sheet-to-sheet. For a glass substrate to have good TPV performance, the substrate must have the required balance of physical properties to resist the various causes of strain of the substrate: elastic distortion, stress relaxation, and compaction. These sources of strain, and the corresponding glass property that resists them, are discussed below.

In TFT processes, there are several sources of stress applied to the glass substrate, such as film stresses and gate metals. In oxide TFT, the latter is particularly significant due to the substantial thickness and covered area of the gate metal. The pitch change associated with these stresses is determined by the size of the stress, the elastic modulus of the glass, and the thickness of the substrate. Since the stresses are determined by the TFT manufacturer and the industry is continually driving to thinner and thinner substrates, the only attribute within the control of the glass manufacturer is to increase the elastic modulus to increase the stiffness of the substrate. Also, because the stresses in the TFT process can vary across a sheet or sheet-to-sheet, a higher elastic modulus will reduce the strain due to variations in the applied stresses, thereby minimizing TPV from this potential cause.

The stresses from applied films and gate metal can also contribute to the overall TPV through the relaxation of those stresses during subsequent thermal treatments. As the substrate progresses through the various steps of the TFT process, the films, gate metal, and substrate itself will all undergo stress relaxation. As the stress state of the composite changes with time and temperature, the concomitant strain will accordingly change, causing a pitch change and an increase in TPV. The glass substrate resists this stress relaxation in proportion to its effective viscosity at the process temperatures. In a-Si TFT processes, the temperatures are low enough that there is a minimal amount of stress relaxation due to the glass substrate having a relatively high viscosity at these low temperatures (the viscosity of the glass increases as the temperature decreases). In oxide TFT processing, however, temperatures are higher and, therefore, the potential for stress relaxation is greater due to the lower effective viscosity of the glass. This is particularly acute for the BCE oxide TFT process, which has process steps with temperatures in excess of 400°C. Traditional glass substrates which are sufficient for the typical a-Si applications may also be sufficient for the lower temperature ESL oxide TFT processes. However, the higher temperature BCE oxide TFT process may require a substrate with a higher effective viscosity at temperatures in the range of 400°C.

The effective viscosity of the glass substrate also plays a role in the amount of viscous relaxation the glass substrate undergoes in the TFT process due to structural relaxation of the glass itself. This is commonly referred to as “compaction” or “shrinkage” in the glass industry. Compaction is due to the evolution of the glass structure from a non-equilibrium state toward a structure closer to equilibrium with the customer process. The amount of this viscous relaxation that occurs is proportional to the degree to which the glass is out of equilibrium, and inversely proportional to the effective viscosity of the glass at the TFT process temperatures. Consequently, a higher viscosity glass is beneficial for minimizing TPV, just like in stress relaxation. In glass property terms, a higher viscosity glass is a glass with a higher “annealing point” therefore glass manufacturers will often tout the high annealing point of their glass compositions.

Corning’s proprietary fusion process manufactures glass panels at Gen 10.5 sizes (2940 x 3370mm), enabling higher glass utilization for larger-screen sizes. For example, one sheet of Gen 10.5 glass could create eight 65” display panels, or six 75” display panels. This enhanced glass utilization greatly reduces cost for panel makers and is key for enabling the oxide TFT market"

For oxide TFT to be used in IT or handheld products, one of the key features is a thin and light form factor. To achieve this, the display panel usually needs to be thinned down to roughly 0.15mm / 0.15mm (for the two pieces of glass in the display) using the chemical slimming process. A faster etch rate is clearly desired to enable higher throughput and lower costs but this often comes at the cost of the generation of “sludge.” Sludge can create problems in the etch vendors’ processes and end up causing more cost than the fast etch rate reduced. By using a glass that balances maximizing etch rate while minimizing sludge generation, panel makers optimize their throughput and costs.

The technology challenges and technical requirements outlined fuel an industry need for a new glass substrate with the right balance of physical properties for oxide TFT technology. For displays applications, this includes low total pitch variation, low total thickness variation, and low sag. This package of glass attributes, alongside the ability to scale-up manufacturing to large-gen sizes, will help enable the next-generation of mid-to-large-size, immersive displays in 8K TVs.

These applications require a shift toward oxide technology, versus the current a-Si and LTPS TFT technologies. As the push for oxide increases, new process and technical challenges emerge for panel makers. To build a display that meets these performance expectations, panel makers require a thermally and dimensionally stable glass to improve yields while achieving the desired resolution.

One of the industry’s leading oxide panel makers selected Astra Glass as its backplane glass substrate because it has the inherent fidelity to thrive in high-temperature oxide-TFT glass fabrication for immersive high-performance displays.

One of the industry’s leading oxide panel makers selected Astra Glass as its backplane glass substrate because it has the inherent fidelity to thrive in high-temperature oxide-TFT glass fabrication for immersive high-performance displays.

One of the industry’s leading oxide panel makers selected Astra Glass as its backplane glass substrate because it has the inherent fidelity to thrive in high-temperature oxide-TFT glass fabrication for immersive high-performance displays.

One of the industry’s leading oxide panel makers selected Astra Glass as its backplane glass substrate because it has the inherent fidelity to thrive in high-temperature oxide-TFT glass fabrication for immersive high-performance displays.

Samsung Display, one of the leading amorphous silicon (a-Si) TFT LCD manufacturers for the past 20 years, is shutting down its first G7 line, Line 7-1, from as early as the end of July and there are rumors of a few more fab closures to come. Its a-Si TFT LCD footprint is expected to shrink dramatically over the next few years with potentially just one a-Si fab in operation in 2018 to serve its market-leading TV business.

Panasonic LCD is also rumored to be shutting down most or all of its G8.5 line. Based on the near term decline in a-Si TFT LCD capacity, Credit Suisse upgraded AUO and Innolux on this news and their shares surged.

Samsung’s Line 7-1, which began operation in October 2004 and production in May 2005, is rumored to be shutting down from the 30th July through the end of the year. It has a unique glass size (1,870 x 2,200mm), which was the largest in the world at the time of its introduction and is optimized for both 40” and 46” LCD TV panel production. It was also the site of the Samsung-Sony joint venture, S-LCD, established in April 2004. This line enabled Samsung and Sony to rapidly take share from smaller G6 fabs optimized for 32” and 37” panels. During that time, the two companies competed aggressively in retail while establishing 40” and 46” as mainstream sizes. The JV with Sony ended in 2011. S-LCD also built an 8th gen fab that began production in Q3’07, and Samsung built a second G7 line (L7-2) on its own, with even more capacity at over 170,000 substrates per month. L7-2 began production in Q3’08.

Displays are already a weak spot in Samsung’s financial performance. The category caused the device solutions division to be the only one to suffer a loss among all major divisions within Samsung in Q1’16, and its revenues of KRW6 trillion ($5.2 billion) were the lowest in two years. The display division alone posted an operating loss of KRW270 billion ($233 million) in Q1’16 resulting in an operating margin of -4.4%. While Samsung has a number of technology and capacity advantages in OLEDs for mobile displays, its a-Si TFT LCD business has matured and is increasingly becoming commoditized, as new entrants from China with government support are taking share. In addition, most of the a-Si TFT LCD market segments have become stagnant or are in decline, which points to more losses given the growing Chinese competition. On the other hand, OLEDs and flexible OLEDs are poised for rapid growth as they take share. As a result, it makes good business sense for Samsung to exit much of the a-Si TFT LCD market.

That is not all, however. Line 6, Samsung"s last 5th gen line with 1,100 x 1,300mm substrates and around 190,000 substrate per month capacity, is also expected to be shut down, according to industry insiders. That line, which features a-Si and oxide TFT LCD production, has been producing tablet, notebook PC and LCD monitor panels. Those markets have also been hit by stagnant demand, growing competition from China, commoditization and declining margins. This line is expected to be shut down between the end of 2016 and 2017. Line 6 is predicted to be converted to a semiconductor facility, making application processors for smartphones and tablets.

If Samsung closes down Line 6 and Lines 7-1 and 7-2, its a-Si production will be down to just two G8.5 fabs: one in Suzhou, China and one in Tangjong, Korea. The Suzhou fab, ramping to over 100,000 substrates per month, is also rumored to be a candidate for sale with Chinese and Indian TFT LCD suppliers as potential customers. If Samsung licenses its latest a-Si TFT LCD or oxide TFT LCD technology, that would certainly make the sale more attractive. This means Samsung would have just one a-Si TFT LCD fab: Line 8.

I believe Line 8 will be sufficient for Samsung to support its internal TV brand with leading edge panels for the TV market as it has a monthly capacity of 400,000 2,200 x 2,500mm (G8.5) substrates. Samsung’s TV business would likely continue to outsource its low-end panels for its TVs to other LCD manufacturers and focus this fab on higher margin products such as 8k, HDR, QD WCG, etc. I cannot see Samsung abandoning LCD TV panel production until it believes OLEDs are cost effective enough to takeover the mid-range high end of the TV market. This likely means not until OLED materials can be inkjet printed, Samsung is still likely to focus all of its TV panel production on LCDs.

If this occurs as described, Samsung Display"s output of 42" and larger panels would be LCD, and sub-42" would be OLED, although it may not have much production between 15" and 40". This would be an amazing, but expected, transformation given the supply/demand and profitability outlook for the a-Si market.

2016 and 2017 are expected to be back-to-back years of over $12 billion in LCD/OLED equipment spending. Unless these fabs struggle with their ramp and their yields, the a-Si market will continue to be oversupplied although conditions should improve in the 40”-43” market in the second half of 2016.

Rather than battle it out with government-subsidized Chinese players, Samsung appears to be accelerating its exit of the increasingly commoditized a-Si TFT LCD market. This should please its shareholders, especially if it can sell all its old equipment and license its a-Si technology for a royalty, but will be harmful to some of its suppliers. It is also likely to protect its TV business by holding onto its most competitive fab, but will increasingly become an OLED company. Interesting questions as a result of these moves include:

A couple of days after this article was originally posted, it was claimed - and later denied by a company official - that Samsung will move its a-Si TFT LCD operations out of Samsung Display and into Samsung Electronics. Such a move aligns perfectly with its intention, indicated above, to close its a-Si fabs as in a couple of years its a-Si TFT LCD operations may be limited to providing panels to its TV business. - Ross Young

Ross Young is the CEO and Founder of Display Supply Chain Consultants. He also serves on the Board of Directors of publicly traded touch sensor manufacturer UniPixel and diamond semiconductor developer Akhan Technologies. He previously founded DisplaySearch and served as its CEO from 1996 - 2007 where he launched most of their categories of coverage. He has also held executive positions at Samsung LCD and IMS Research.

.jpg)

Thin-Film transistor (TFT) complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) devices have recently attracted significant attention and have been widely studied. TFTs—Thin-Film-type devices—have the advantages of high field-effect mobility, high uniformity over large areas, and high optical transparency in the visible range. In an LCD, each liquid crystal pixel is driven by a TFT integrated behind it, achieving high speed, brightness, and contrast for display screen information. Most conventional TFTs are amorphous silicon and low-temperature polycrystalline silicon metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs). Such silicon-based TFTs and related devices typically have the following characteristics:Conventional silicon-based TFTs can easily achieve n- and p-Type doping, which is convenient for preparing complementary logic devices.

Dramatic advancements in transparent conductive oxide (TCO) devices (such as solar cells or low-contact-resistance materials for OLED) and flexible transparent electronics have been recently reported [1,2], which has made further improvements in the response speed and reduction in the power consumption of TFTs necessary. As the transistor size decreases, the response speed increases. Meanwhile, a smaller transistor size reduces the overall chip supply voltage, thus lowering the power consumption. However, it is difficult to advance silicon-based TFTs to achieve the high transparency required by modern technology, because mainstream silicon-based CMOS technology has developed to a 10 nm process node that is difficult to upgrade, leading directly to its process peak reaching the limit of transparent pixels. With the current process, it is difficult to obtain high-quality large-diameter silicon ingots [3,4]; thus, the development of silicon-based transistors has encountered significant hardships. As the market demand for more integrated and functionally complex integrated circuits increases, although the electrical properties of silicon-based TFTs are easy to control and suitable for the preparation of TFTs, the increase in market demand for more integrated and functionally complex integrated circuits highlight their drawbacks of low mobility, low stability, and poor light transmittance, making it difficult to achieve high-resolution and large displays [5].

Fortunately, oxide TFT devices with oxide semiconductors as the core materials can overcome the shortcomings of silicon-based TFTs. Currently, oxide TFTs with high electrical conductivity and high optical transmittance—such as wide-bandgap semiconductors or insulators—are a promising alternative. However, the bandgap width affects the conductivity and transparency of the material. Metallic materials have high conductivity but are opaque, making them an unsuitable alternative. A material with good transparency and a wide bandgap implies a low carrier concentration, which makes the material poorly conductive. However, high conductivity and transmittance in the entire visible region can only be achieved when the material has a bandgap greater than 3 eV and the carrier concentration is between 1019 and 1020 cm−3. The high transmittance in the visible region due to the wider optical bandgap leads to the reduced absorption of visible photons, resulting in poor material conductivity. Alternatively, carriers can be introduced through elemental doping to improve the conductivity of the material. Owing to their superior field-effect mobility, stability, and responsiveness compared to silicon-based TFTs, the development of oxide TFTs has greater potential—particularly in future-oriented integrated industrial circuits [6,7,8,9].

However, owing to the difficulty of achieving p-Type doping of oxide semiconductors, current devices based on oxide semiconductors only use n-type TFTs with unipolar characteristics [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The development of p-Type transistors has only just begun (e.g., Figure 1) [18,19]. Compared with n-type oxide semiconductor devices, the mobility of p-Type oxide semiconductor devices is 3–4 orders of magnitude lower. n-type TFTs have been developed in the industry, with low temperature, good economy, and mature technology, while p-Type TFTs are still in the experimental stage. Their performance remains unsatisfactory in terms of the switching ratio and threshold voltage, which has become a bottleneck hindrance [20,21]. To improve the performance of CMOS devices for applications that include image sensing in analog and digital electronic systems [22,23], the development of p-Type TFTs is necessary (e.g., Figure 2).

Performance of n- and p-channel tin oxide TFTs [24]: (a) Output and (b) transfer characteristics of tin oxide p-channel TFTs using ALD-Al2O3 as a gate dielectric. (c) Output and (d) transfer characteristics of tin oxide n-channel TFTs using SD-Al2O3 as a gate dielectric.

In metal oxides, the atoms of the metal are bonded with oxygen atoms through ionic bonds [25], while the 2p energy level of oxygen is much lower than the valence band electron energy level of metal. Owing to the strong electronegativity of oxygen ions as a strong localization-binding effect on the hole at the valence band maximum (VBM), even if a mass hole is introduced at the VBM, it forms a deep and dominated energy level, resulting in the low mobility of the hole carrier in the material. Hence, to fabricate CMOS circuits, p-Type TFTs with a performance similar to that of n-type TFTs are required. However, the development of high-performance p-Type oxides is severely limited because of the low p-Type VBM hole mobility.

In recent years, many studies have been carried out on p-Type oxide semiconductors [19,26,27,28,29,30]. In [19], the potential applications of material physics, various device structures, and the great potential of low-power electrons, transparent electrons, display applications, gas sensors, etc., are discussed. In the past five years, p-Type oxides have shown better stability, and the switching ratio of devices has been further improved. A few oxides have a unique energy band structure in which the VBMs are inherently modified by the co-hybridization of metal orbital states with the 2p orbitals of oxygen, which results in the reduction in the binding effect of the 2p orbitals of oxygen on hole carriers, improving the mobility of hole carriers and making p-Type conductivity in the material achievable. In this review, the recent processes for fabricating nickel oxide (NiO), tin oxide (SnO), and cuprous oxide (Cu2O) TFTs with p-Type characteristics are summarized. In Section 2, the unique valence band top of oxide semiconductors with p-Type characteristics is classified, and the performance characterization of TFTs is explained. The following three sections introduce the latest progress of p-Type NiO, SnO, and Cu2O TFTs, respectively, in terms of materials, manufacturing technology, and performance. In Section 6, the current issues and research progress of p-Type oxide TFTs are summarized. Finally, in Section 7, suggestions for the future research directions related to practical applications are put forward.

Thin-Film Transistor Liquid Crystal Displays use thin-film transistors to control the voltage applied to the liquid crystal layer at a sub-pixel level. The structure of TFT LCDs consists of a TFT “sandwich” and a BLU (Backlight Unit). A typical configuration is shown in the schematic diagram below.

Firstly, between the back and front polarizers, TFT LCD cells are made with two glass substrates – one for color filters, the other for a TFT array – and a liquid crystal layer sandwiched in between.

For normally black TFT LCDs, if we follow along a piece of light setting off from its backlight source, it will bea)guided uniformly by LGP;b)reflected and enhanced by BEF and DBEF;c)polarized by the back polarizer;d)polarization changed by twisted LC under the voltage applied by TFT arrays;e)“tinted” red/green/blue by corresponding color filter of the subpixel;f)let through the front polarizer by matched polarization; andg)finally, it will reach the surface and appears in viewer’s eyes.

Normally black LCDs have higher contrast and wider viewing angles without grayscale inversion phenomenon compared to their normally white relatives. And whether TFT LCDs are normally black or white depends on their LC switching mode:

Optical and SEM (scanning electron microscopy) images of fabricated (a, b) CL and (c, d) CLSE pixel structures. The five white line patterns in (d) are the ITO interdigitated pixel and common electrodes. (e) Images from the normal direction and from 50 degrees to the left and right of a 2.3-inch-diagonal display incorporating the IPS TFT-LCD panel. (f) The three-black matrix (BM) patterns (top: BM covering both gate and data lines, middle: BM covering only the data lines, and bottom: without BM) and (g) optical images of pixels without BM (left: LC on and off voltages supplied to every other data line, right: LC off voltage supplied to all data lines).

Figure 3e shows images from the normal direction and from 50 degrees to the left and right of a 2.3-inch-diagonal display incorporating the IPS TFT-LCD panel fabricated in our laboratory, (f) the three black matrix (BM) patterns (top: BM covering both gate and data lines, middle: BM covering only the data lines, and bottom: without BM), and (g) optical images of panel areas without the BM (left: LC on and off voltages supplied to every other data line, right: LC off voltage supplied to all data lines). As can be seen in the image from the normal direction, the brightness and contrast of the display area with the top BM and middle BM patterns are almost the same, but the contrast of the display area without the BM is relatively lower because of the lower darkness level of the LC off pixels indicating “HITACHI”. As shown in Fig. 3g, this is due to light leaking through the aperture between the data line and adjacent common lines. Therefore, in the CL structure, the BM on the drain line is necessary to obtain a high contrast ratio by shielding light leakage. This is the same as in the conventional structure. On the contrary, there is no light leakage along the gate line through the gaps between the gate line and edges of the pixel/common electrodes, as is clearly shown in Fig. 3g. This is a unique advantage of the CL structure because the conventional structure must shield these gaps with the BM to prevent light leakage. The suppression of light leakage along the gate line in the CL structure is due to the driving scheme (see Fig. 2b,a for a comparison with the conventional structure). During the holding period (tOFF) in the conventional structure, regardless of the pixel voltage, Vp (including Vp = 0), nonzero Vgp and Vgc are always applied to keep the TFT off, and these voltages are applied to the LC layer, inducing light leakage as reported in

Figure 4a shows the gate voltage (Vg) dependence of the panel brightness, while the inset shows that of the TFT current (transfer characteristics). The gray curves are for the conventional IPS TFT-LCD with the TFT before enhancement, the common line, and the matrix BM (MBM) shown at the top of Fig. 3f. The blue curves are for the proposed CL structure with the enhanced TFT and the stripe BM (SBM) shown in the middle of Fig. 3f. In this case, enhanced TFT characteristics were obtained by using an MNOS TFT without back-channel oxidation that was enhanced by the BTS process. In both structures, the threshold voltages for panel brightness, defined by extrapolating the straight part of the brightness curves, reflect those of the TFT transfer curves defined as Vg at a drain current of 10−12 A, and they are well matched to be 4 V and 9 V, respectively. The maximum brightness for the CL structure is 137% higher than that for the conventional structure, which is due to the increase in the aperture ratio from 38 to 52% that results from the elimination of the common line and the BM covering the gate line.

(a) Dependence of panel brightness and TFT current on gate voltage for the conventional pixel structure of 38% aperture ratio (AR) with matrix black matrix (MBM) over both drain and gate lines and proposed CL pixel structure of 52% AR with strip black matrix (SBM) over only the drain lines. Transfer characteristics before and after bias temperature stress (BTS) treatment are shown in the inset. (b) Charging and (c) holding characteristics of enhanced TFT of the CL structure with gate as a common line. Vg and Vd in the TFT ON state are 30 V and +/−7 V, respectively.

To estimate the charging and holding characteristics of the MNOS-enhanced TFT in the panel, the gate TFT ON and OFF time dependences of the panel brightness were measured (Fig. 4b,c). The charging characteristics in Fig. 4b are plotted as a function of tON at tOFF = 16.6 ms, Vg = 30 V, and Vd = ± 7 V. The holding characteristics in Fig. 4c are plotted as a function of tOFF at tON = 34 μs. 95.1% charging at tON = 34 μs and 95.3% holding at tOFF = 16.6 ms indicate that the enhanced TFT has sufficient charging and holding performance to drive a standard VGA (640 × 480 pixels) panel (the number of scanning lines is estimated as tOFF/tON = 16.6/0.034 = 488).

To confirm the driving conditions for the CL structure without the BM along the gate line (with the SBM), the tOFF dependence of the contrast ratio (CR) in the CL panel was further investigated as shown in Fig. 5a, where CR is plotted as a function of tOFF for the CL panels with the matrix BM (MBM) and the strip BM (SBM). The inset shows the brightness in the bright (Vd = 7 V) and dark (Vd = 0 V) states of the CL panel with the SBM as a function of tOFF and an optical image of the panel with tOFF = 6.4 ms. The SBM and MBM panels keep CR higher than 240 with tOFF > 16.6 ms, the frame period of a display panel without flicker being noticeable to the human eye. both panels decrease CR when tOFF is less than 16.6 ms; the CR of the SBM panel decreases faster than the CR of the MBM panel. As shown in the inset, the decrease in CR was due to the increase in dark-state brightness with decreasing tOFF as light leakage increases along the gate line. This light leakage is induced by the voltage Vgp = Vgc = VgON = 30 V applied only for 34 μs during the TFT ON (charging) state, which is 1/488th the duration, tOFF = 16.6 ms, of the TFT OFF (holding) state with Vgp = Vgc = VgOFF = 0 V, but the ratio increases with decreasing tOFF and becomes effective enough to switch on LC layer and induce light leakage. However, it should be stressed again that the CL panel with the normal holding (TFT OFF) time of 16.6 ms does not suffer from the light leakage along the gate line, so the aperture ratio can be increased by removing the BM along the gate line.

Figure 6 indicates the effect of bias temperature stress (BTS) on the TFT characteristics. As the stressing time, tS, of the positive gate stress voltage, Vst = + 77 V, increases from 0 to 3600 s, the transfer (Id-Vg) curve shifts in the positive direction (Fig. 6a). Vth is defined as Vg at which Id = 10−12 A and ΔVth is defined as the Vth shift from the initial value via BTS. As shown in Fig. 6b, ΔVth increases logarithmically with increasing tS: ΔVth = 2.17 + 4.93 × log (tS). The mechanism behind the gate-stress-induced Vth shift is electron tunnel injection from the a-Si:H semiconductor into the SiOx gate insulator. For confirmation, ΔVth of MNOS TFTs with different SiOx thicknesses is plotted as a function of the electric field applied to the SiOx layer in Fig. 6c. Here, the thickness of the SiOx was varied (5, 10, 20, 50 nm), while the SiN thickness was fixed at 200 nm. The electric field applied to SiOx, Eox, was calculated using the following equation,

Effect of bias temperature stress (BTS) on TFT characteristics. (a) The transfer (Id–Vg) curve shifts in the positive direction with positive gate bias stress of Vst = + 77 V over the duration of 0–3600 s. (b) ΔVth, defined as the Vth shift from the initial value via BTS, increases logarithmically with increasing tS, following ΔVth = 2.17 + 4.93 × log (tS). (c) ΔVth of MNOS TFTs with different SiOx thicknesses from 5 to 50 nm as a function of the electric field applied to the SiOx layer.

Figure 7a shows the effect of back-channel oxidation (BCO) and passivation (PAS) on the Id-Vg characteristics of the MNOS TFT. The Id-Vg curve with Vth = 5.1 V is further enhanced to Vth = 10.9 V after BCO, although there is a slight degradation of the slope of the current increase in the sub-threshold region. The slope recovers after PAS without any change to the enhanced characteristics

(a) Effect of back-channel oxidation (BCO) and passivation (PAS) on Id–Vg characteristics of MNOS TFT. (b) Vth and Vth standard deviation, σVth, after BTS and after BCO without BTS treatments and (c) SiOX thickness as a function of position along gate-line, x.

The advantage of BCO over BTS is the uniformity of the enhanced characteristics; Fig. 7b shows the distribution of the enhanced Vth as a function of position along gate-line, x, for the MNOS TFTs connected with a 90-mm-long gate line in the TFT substrate after BTS and BCO treatments. The average value of Vth and the standard deviation, σVth, for pristine TFTs before BTS or BCO, are 5.1 V and 0.35 V, respectively. After BCO, Vth is uniformly enhanced, with an average Vth = 11 V and σVth = 0.4 V without increasing σVth. On the other hand, after BTS, Vth is nonuniformly enhanced with an average Vth = 9.3 V and σVth of 1.4 V. In particular, Vth increases linearly as a function of position along gate-line, x. As the gate SiOx thickness linearly decreases, from (54 nm) to (47 nm) with increasing x as shown in Fig. 7c, the increase in ΔVth after BTS with x is due to increase in the electric field applied to SiOx as shown in Fig. 6c and Eq. 1.

It has been shown that the Vth of the MNOS TFT is independent of the gate SiOx thickness when the thickness is more than 5 nm8a, Vth of the MNOS TFT with the BCO treatment becomes almost independent of the BCO SiOx thickness. As shown in the inset, the thickness of BCO SiOx composed of oxidized a-Si:H linearly increases with BCO processing time, and the Vth increase almost saturates at a BCO SiOx thickness greater than 5 nm. Therefore, the enhanced MNOS TFT after BCO has a uniformly high Vth that is robust to thickness fluctuations of the gate and BCO SiOx layers. BCO also has an advantage over BTS in terms of the stability of Vth as shown in Fig. 8b, which plots the annealing time dependence of Vth for BCO and BTS. In this experiment, the stoichiometry (x) of the gate SiOx was 1.78 for BTS and 1.78 and 1.9 for BCO. The annealing temperature in the N2 atmosphere was 200 °C. In the case of BTS, Vth decreased to the pristine value after approximately 5 h of annealing, while Vth decreased more slowly in the case of BCO. In particular, the annealing time required for Vth to fall to 7 V was 7.5 times longer than that of BTS. Increasing the stoichiometry (x) of the gate SiOx dramatically improved the BCO-enhanced Vth to as much as 11 V, which was stably maintained after 24 h of annealing at 200 °C.

(a) Dependence of Vth on thickness of back-channel oxidized (BCO) SiOX. The inset shows the SiOx thickness dependence on the BCO process time for RF powers of 200 W and 500 W. (b) Stability of Vth as a function of annealing time for three different TFTs with gate SiOx stoichiometry, x = 1.78 and bias temperature stress (BTS), x = 1.78 and BCO, and x = 1.9 and BCO. The temperature of annealing in the N2 atmosphere was 200 °C. (c) Band diagram of back-channel oxidized MNOS TFT. The red arrows show the electric dipoles at the SiOX/a-Si:H and a-Si:H/BCO SiOX interfaces.

A schematic band model for the MNOS TFT with the BCO treatment and the sectional structure of the interface between the a-Si:H and gate and BCO SiOx are shown in Fig. 8c. The uniformly high Vth that is independent of SiOx thickness is due to the dipoles generated at the channel and back-channel interfaces between a-Si:H and SiOx8 of reference

A TFT LCD, or a thin film transistor liquid crystal display, is one of the fastest growing forms of display technology today. The thin film transistor (TFT) is a type of semiconductor device used in display technology to enhance efficiency, compactness, and cost of the product. In conjunction with its semiconductor properties, the TFT LCD is an active matrix display, controlling pixels individually and actively rather than passively, furthering the benefits of this semiconductor device.

The TFT LCD is built with three key layers. Two sandwiching layers consist of glass substrates, though one includes TFTs while the other has an RGB, or red green blue, color filter. The layer between the glass layers is a liquid crystal layer.

The Architecture of a TFT Pixelbelow) from the other substrate layer of the device and control the amount of voltage applied to their respective sub-pixels. This layer also has pixel electrodes between the substrate and the liquid crystal layer. Electrodes are conductors that channel electricity into or out of something, in this case, pixels.

On the surface level is the other glass substrate. Just beneath this glass substrate is where the actual pixels and sub-pixels reside, forming the RGB color filter. In order to counteract the electrodes of the previously mentioned layer, this surface layer has counter (or common) electrodes on the side closer to the liquid crystals that close off the circuit that travels between the two layers. In both these substrate layers, the electrodes are most frequently made of indium tin oxide (ITO) because they allow for transparency and have good conductive properties.

The outer sides of the glass substrates (closest to the surface or closest to the back) have filter layers called polarizers. These filters allow only certain beams of light to pass through if they are polarized in a specific manner, meaning that the geometric waves of the light are appropriate for the filter. If not polarized correctly, the light does not pass through the polarizer which creates an opaque LCD screen.

The twisted nematic effect is one of the cheapest options for LCD technology, and it also allows for fast pixel response time. There are still some limits, though; color reproduction quality may not be great, and viewing angles, or the direction at which the screen is looked at, are more limited.

The light that passes through the device is sourced from the backlight which can shine light from the back or the side of the display. Because the LCD does not produce its own light, it needs to use the backlight in the OLED) have come into use as well. Typically white, this light, if polarized correctly, will pass through the RGB color filter of the surface substrate layer, displaying the color signaled for by the TFT device.

Within an LCD, each pixel can be characterized by its three sub-pixels. These three sub-pixels create the RGB colorization of that overall pixel. These sub-pixels act as capacitors, or electrical storage units within a device, each with their own independent structural and functional layers as described earlier. With the three sub-pixels per pixel, colors of almost any kind can be mixed from the light passing through the filters and polarizer at different brightness based on the liquid crystal alignment.

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey