display screens for exhibitions quotation

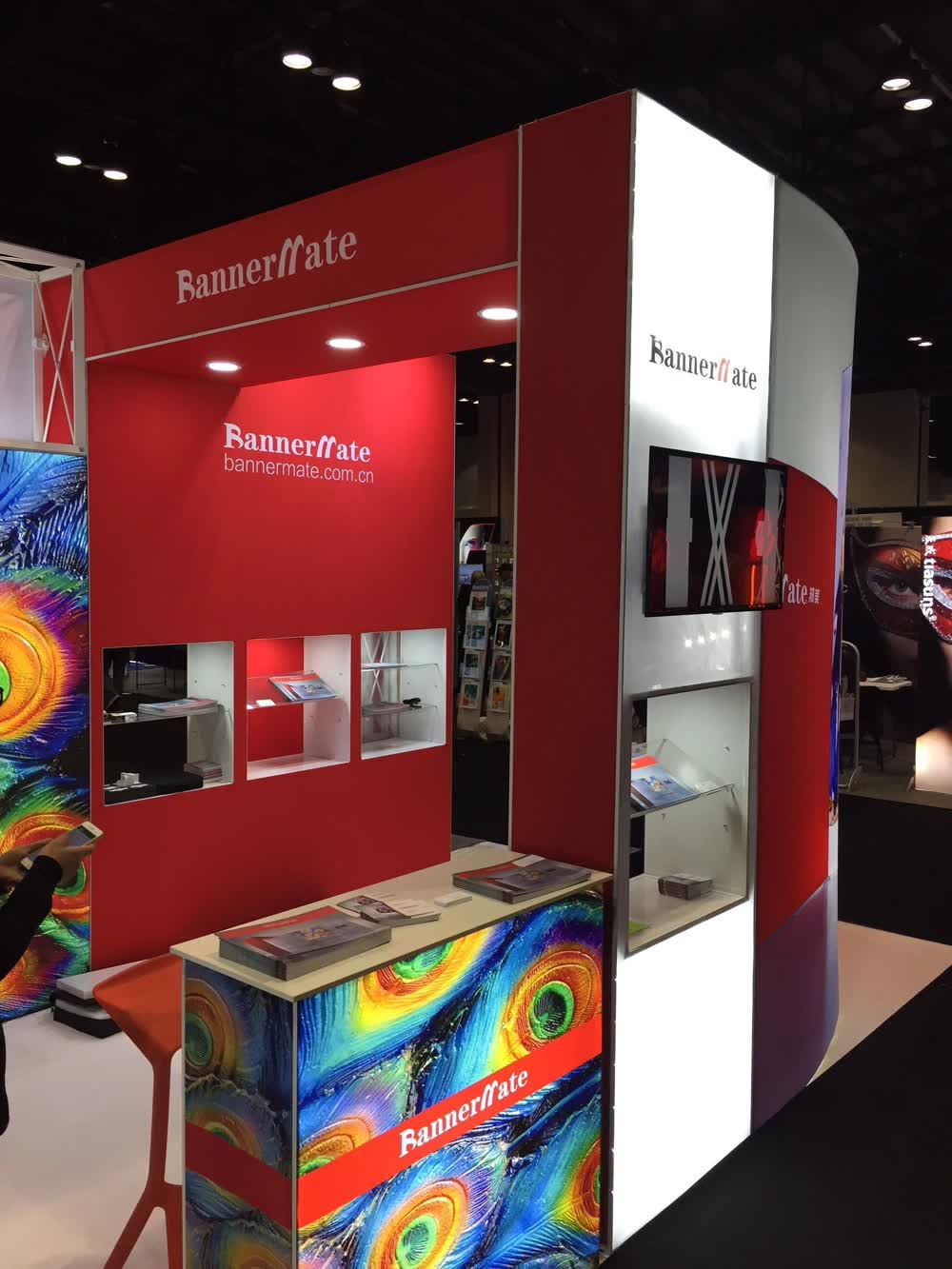

Our excellent T3 system is a perfect solution to the challenge of owning an exhibition stand system that is expandable, re-usable, totally flexible and looks a million dollars. We will design and deliver the ideal system or display unit for you quickly and at lowest possible cost.

We sell a wide selection of portable exhibit displays that are designed to meet your trade show, convention, and presentation needs. Portable exhibits, such as portable graphic displays, hook & loop display booths, and tabletop display boards, offer a great way to sell your products and services at promotional events. Our complete line of portable exhibit displays includes everything you need to make your next event a success.

Portable exhibits can make all the difference in the experience that a company has at a tradeshow, convention or expo. With the ease of these portable exhibit displays, you can be into the exhibition hall and have your display set up in no time! These portable exhibits offer lightweight, easy to setup, flexible designs that will help you present your products and services with professionalism and style. Tradeshows and other promotional events can be a crucial part of making your business a success; they give your company invaluable exposure and allow you to reach hundreds of people at one time. These portable exhibits help you to put your best foot forward and show your customers what you are selling and why they should invest in you. Our line of portable exhibit displays includes everything you need for a successful exhibit. We sell everything from pop up displays and hook & loop-receptive booths, to hanging banners, literature holders, and accessories.

We sell portable exhibits with every need and budget in mind. A great way to get a customized exhibit booth at a low cost is with our line of inexpensive tradeshow exhibit displays. These exhibit booths have 10 panels that allow for quick assembly and are covered in hook and loop receptive material. The lightweight panels fold and snap together which allows you to move from one location to another with ease. These portable booths are ideal for companies that need to get in and out of a tradeshow quickly. All of these boards are made with hook & loop-receptive fabric so you are able to attach any accessory such as posters, sell sheets and acrylic accessories to your display. We also sell more upscale adjustable trade show displays that are covered in hook and loop receptive material. These exhibit booths feature a pop up frame and come in a variety of styles, sizes and colors. Both of these options allow you to customize your display to your particular needs, and come with the option of a customized header. In addition to display booths covered in hook & pile-receptive fabric, we also sell portable exhibits with pop up frames and huge, custom color graphics. Both our lightweight graphic pop up displays and our high resolution graphic portable exhibits make excellent backdrops in trade show and convention booths.

Exhibit booths are not all you need to make a trade show or convention display successful. As a part of our line of portable exhibits, we also sell banner stands, literature holders, portable flooring, table covers, and more, all of which are designed to enhance your trade show displays. Portable banner stands offer a great way to add eye-catching graphics at the entrance of your booth, while iPad display stands get your information out to potential customers and clients. Portable counters offer a convenient place to display literature and demonstrate products, while portable flooring can ease the feet of tired show-goers. Booth accessories can also help separate you from the competition with fit and finish. Spotlights and banner lighting also help make your message

Portable exhibits, such as pop up booths, banner stands, and more, offer a great way to advertise your business at trade shows and other promotional events. We sell all of the portable exhibits that you need to make your next event a success one. In addition to portable tradeshow displays, Displays2go is one stop shopping for all of your point

of purchase needs including ballot boxes, sign holders, lecterns, stanchions and literature stands. Thousands of products are in stock and ready to ship to you. We have been manufacturing and shipping pop products for over 40 years and our

product line continues to grow daily. Orders can be easily placed from our website or over the phone. Our staff is waiting for your order. In addition, our design sales team can quote and prototype your custom sample requests in hours not days.

Please report this problem using the form below. The information you provide will be used to troubleshoot the problem. It won"t be shared or used for any other purpose.

A 50″ TV monitor starts at $325 for a 1-day rental. TV rental pricing depends on monitor size, quantity, rental duration, and additional accessories needed. Meeting Tomorrow offers a Best Price Guarantee where we’ll beat any competitor quote by 5%. Contact 1-877-633-8866 for an immediate quote.

Our HD TVs, touch screen displays, and 4k monitor rentals come in a variety of sizes from 32” to 90” from Samsung, NEC, Sharp, Panasonic, and other professional brands. Call 1-877-633-8866 to ask about availability and reserve your monitor rentals.

We are happy to learn the details of your event and recommend the perfect solution for you. When choosing a display size, we consider attendee count, venue layout, the content you’ll be presenting, and more. Call (877) 633-8866 and we’ll help you figure out the details or check out our article How to Rent the Right Size TV for Your Event.

Yes, TV monitor rentals are available anywhere in the U.S. and Canada, including all hotels, offices, and meeting locations. We offer delivery, setup, and on-site support for all display orders, and floor stands and wall mounts are available for all flat screen monitor rentals.

In order to use your monitor, you’ll need a floor stand or wall mount, cabling, and a content source like a laptop computer or USB media player. Meeting Tomorrow can provide you with everything you need to get your monitor up and running, plus any other AV equipment for your event.

Our TV monitor rentals can display content from a laptop computer or from a USB media player / USB stick. We also provide laptop computer rentals and any cabling you need for your monitor setup.

If you find a quote for the same equipment less than our price, we will beat it by 5%. All you need to do is provide us the quote you found from another competitor. Call (877) 633-8866 and we’ll help you make sure you’re getting the best price.

T3 Systems is manufactured, distributed and owned by Tecna Display Ltd, based in London. We have developed into one of the market leaders in the supply, design and manufacture of Modular Display Stands & Modular Display Systems.

Modular display companies, exhibition, display and interior contractors around the world are using T3Systems’ solutions to build dynamic structures and display environments for exhibition stands, graphic displays and signage, conferences, events, museums and retail interiors.

Our core product philosophy is Twist– Lock – Connect. All products manufactured and designed by Tecna Display Ltd are Tool – Free solutions resulting in ease of storage and transport, design flexibility and speed of assembly.

The excellent T3 Airframe and system is a perfect solution to the challenge of owning an exhibition stand system that is expandable, re-usable, totally flexible and looks a million dollars. We will design and deliver the ideal system or display unit for you quickly and at lowest possible cost.

THE WORLDWIDE LEADER IN TRADE SHOW DISPLAY! Our huge range of Exhibit Displays have been designed to help you stand out from the crowd at your next trade show event. As the world"s leading producer of high-quality custom modular and portable trade show displays, Nomadic Display has helped businesses like yours around the world produce dynamic selling environments. Whether you exhibit in smaller local events or at large international shows, Nomadic"s trade show booths are designed to communicate your company"s specific message effectively, and with striking visual impact meant to enhance your brand. Our exhibit display offerings range from pop up displays and portable displays to tension fabric displays and modular displays. Browse examples of exhibit design, booth rentals, and trade show displays, and explore our exhibit management and support service offerings to learn more about what we can do for you.

Your personal Display Consultant is standing by to explain how the right trade show display can make a significant impact on your next event.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refuseing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We know how challenging it is for a company to take part in a trade fair: the choice of the position of the stand often turns out to be one of the most important factors, as well as the graphics, the selection of furnishings and the advertising material to be prepared and distributed to interested parties, are decisive elements. There is nothing worse for a company than investing in participating in a national or international event and not making an economic profit in the short to medium term thanks to contacts and negotiations initiated at its stand.

The use of a large LED screen at a stand, customized according to your needs, both in terms of size and shape, is today an essential element to ensure maximum visibility to the brand and attract visitors, intrigued by the images shown on the display and by the modernity of the technological solution adopted.

LED screens have made great strides compared to thirty years ago, when solutions were relatively limited. Today it"s possible to use specially designed modules for using the big screen on the occasion of temporary events, which therefore require technical characteristics such as lightness for transport and ease of assembly and disassembly. From this point of view, cabless systems represent one of the most advanced and performing products for the rental market of LED screens as there are no data cables or power cables to connect but it"s enough to place one cabinet next to the other with the use of quick locks, with a great saving of time.

Euro Display has often been a partner of companies and brands for setting up LED screens at Fairs and Expo: among the many participations we mention the collaboration with Lavazza during Expo 2015 in Milan, where a curved Ledwall was set up, wrapped in spiral, over 30 meters long.

We can help any company to stand out from its competitors at Fairs and Expo with high-definition indoor large screens customized according to the size of the stand and the communication needs: contact us for further information and a no-obligation quote.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Browse and buy with exclusive price for your exhibition and retail display system such as pop up display system, bunting stand, graphic standee, brochure holder etc. Only in Manxeon"s Display Store

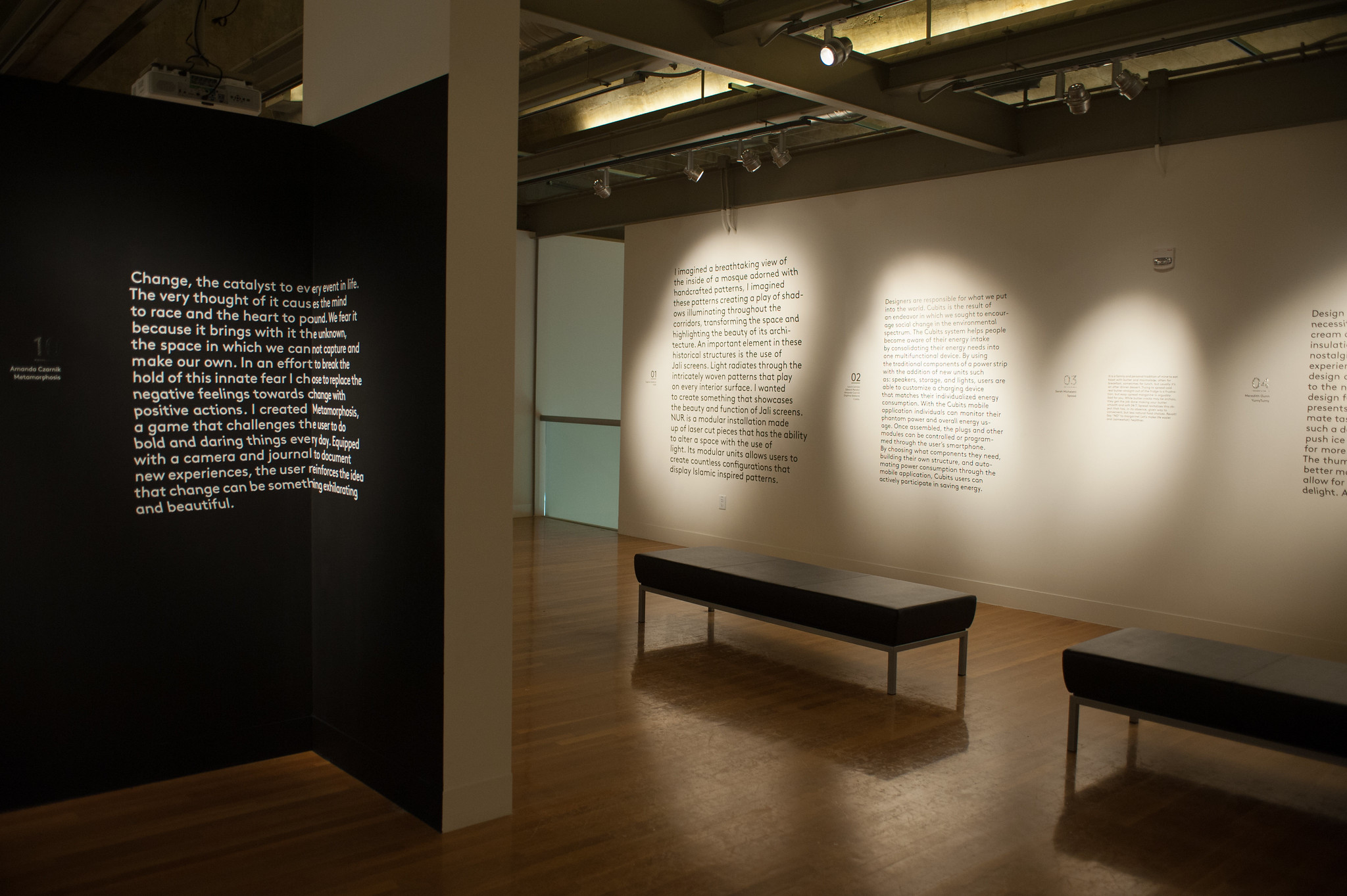

The Style Guide is intended for authors of texts on art—any kind of text—and for editors of these texts and their publishers. Its purpose is to provide guidelines for authors and editors in the writing and redaction of manuscripts. Uniformity of usage is not the purpose of this guide. Rather, it aims to ensure uniformity of comprehension about the issues that authors and editors deal with.

Although it would have its practical purposes, a definitive, this-way-only manual would be inadequate to the profession, since art history is an aggregate of many different methodologies and fields of specialization. Nor is it likely, or expected, that all publishers (or editors) will abandon long-cherished systems, especially when those systems adequately serve their purposes. Rather, we offer a guide to several generally accepted styles. Authors should consult with their publisher/editor before making final stylistic decisions; if the publisher is unknown at the time of writing, the author very often will be responsible for revising the manuscript later to accord with house style.

The style manuals and publications of various institutions were also among the sources consulted for substance and examples. We gratefully acknowledge: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York; the College Art Association, New York; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

This revised edition of the Style Guide, like the original, is dedicated to Virginia Wageman (1941–2003). A co-founder and early president of the AAE, she was an untiring campaigner for high editorial standards. Virginia’s loving devotion to her craft, fund of common sense, and sunny disposition made working with her deeply rewarding.

In general, abbreviations are appropriate in notes and parenthetical or display material but should be avoided in straight (narrative) text. Some publishers prefer to keep abbreviations to a minimum in text, spelling out reigned, circa, born, and so on, even in parenthetical references. Consistency is of primary importance. If you use b. for born, for example, you must used. for died. A list of common abbreviations appears below.

State names are spelled out in running text or when they stand alone. In references, captions, or checklists, standard state abbreviations—Mass. or Calif., for example—can be used. Avoid the two-letter postal-code form (see Chicago 10.28–30). Note, however, that some publishers prefer to spell out state names in all cases, an approach that makes the work more accessible to a global audience.

In running text, spell out: figure(s), note(s), number(s), page(s), plate(s), and catalogue number(s). These may be abbreviated in parenthetical references in text. See below for recommended abbreviations.

Spell out the word Saint in names of saints, but abbreviate it in personal names where the abbreviation is preferred. (Example: Ruth St. Denis.) See below under Saint for rules on church names and other related details.

Unusual diacritical marks should be marked on the manuscript by hand for the designer/typesetter/printer, either called out in the margin or marked with yellow or other highlighter.

Insert all accents given in the foreign language, including accents on capital letters. (Note that diacritical marks are not always used on the first letter of capitalized words in French: Etude, instead of Étude, or Edouard instead of Édouard.)

In running text, lowercase the preceding a museum name. This is to be done even for museums that have the article as part of the official name and capitalize The in their own documents and publications. Example:

In titles of journals, newspapers, or magazines, the preceding the name is lowercase and roman, even if it appears in the masthead for the publication. Examples:

The question of whether to capitalize or lowercase is one of the most common in the field of art history and one of the most difficult in which to attain any agreement. Chicago would lowercase all art movements, periods, and styles except those derived from proper nouns. However, many art historians and art institutions traditionally capitalize them. For this reason, we offer an alternative to the Chicago method.

For names of art movements that have entered the English language as an autonomous word (for example, baroque, meaning “stylistically overwrought”), capitalization of the movement helps to keep the distinction between word and movement clear.

For those who prefer to capitalize art movements, remember that it takes time for a body of works to achieve capital-letter status—to undergo the kind of critical ordering and analysis that ultimately yield a definition. What we now call Conceptual art, for example, generally remained lowercase until the concepts and the works that exemplified it had been articulated over time.

Adjectival forms: Impressionism/Impressionistic or impressionistic; Cubism/Cubist or cubist? Some prefer to lowercase adjectival forms since adjectival forms of proper nouns generally take the lowercase (Pope John Paul’s visit to New York; the papal visit). Others prefer to retain the initial cap to refer unambiguously to the movement, avoiding confusion with another meaning or referent of the word. We lean toward capitalizing any adjectival form that would be capitalized as a noun as the simpler method (thus avoiding such ambiguities as “German expressionist painter”: expressionist of German nationality or of the German Expressionist movement?).

Equally legitimate is the lowercasing of art movements. For some, it merely reflects a tendency to avoid capitalization whenever possible. For others, however, a lowercase baroque or cubism represents an ideological stance, in which the history of art is not a history of great “movements” progressing in linear fashion. But those who use a lowercase style should avoid ambiguities such as “German expressionist painter” (alternative: a painter of the German expressionist movement).

Avoid words and turns of phrase that exclude or are insensitive to readers of a certain gender, race, or religion. Equally, avoid any extremes of political correctness, unless required by the text; for example, the neologism “s/he” is to be avoided.

References to biblical passages (for example, Matt. 4:14) should be made in either the text or notes rather than in the bibliography. The first citation, however, should have an endnote or footnote that provides a full reference and the version of the Bible used (for example, 1 Kings 2:10–12 [New International Version]).

Books and sections of the Bible are usually capitalized (for example, Acts of the Apostles). For abbreviations of books of the Bible, see Chicago 10.45–50.

Two common styles for bibliographies are the “notes and bibliography” system and the “author-date” system. Both are described here, accompanied by sample bibliographies of likely entries for both systems.

In this context, references to “author” mean the name under which the work is alphabetized in the bibliography or list of references; it may be an organization or, as in some exhibition catalogues, the venue (such as New York for the Museum of Modern Art) or venues (New York and Philadelphia).

If the work is accessed online, include its DOI (Digital Object Identifier) or a URL. The latter is less reliable, as a Website may move or disappear. Printed-book publishers may require an electronic-resource identifier in citations for which a source is hard to find.

There are numerous ways to organize a bibliography under the notes and bibliography system. It may be presented as a single list in alphabetical order, or it may be divided into categories, separating sources of a general and a specific nature; books, exhibition catalogues, and articles; in a monograph, works by the artist, works about the artist, and exhibition history. If there is a suggested-reading list, sources for further reading—some of which may have been cited in the text—are given. A bibliography may include all the works cited in the text, or it may be a selected bibliography, which will not necessarily include all the works cited.

Milder, Patricia. “Teaching as Art: The Contemporary Lecture-Performance.” A Journal of Performance and Art 33, PAJ 97, no. 1 (2010): 13–27. doi:10.1162/PAJJ_a_00019.

In long books with many works cited, especially big exhibition catalogues that include references for the objects exhibited, shortened references (the author’s last name and the publication date) are often used in the text. When authors have the same last name, initials are generally added to distinguish them. When there is more than one identical short form (for example, two for Smith, 1957) letters are added after the dates (for example, 1957a and 1957b.)

The author-date system requires a reference list of every work cited in single, alphabetical-list form, giving the author’s full name and publication date as the first items. Footnotes or endnotes can be used to supplement the author-date system.

For capitalization of particles, follow the usage of the named individual or tradition. (In general, lowercase the particle in European names.) Examples:

Asian names: The traditional format for Chinese and Japanese names places the family name first, followed by the given name. Unless the name is Westernized, as it often is by authors writing in English, it should be kept in the traditional order.

In general, capitalize a political entity when it follows the name and lowercase it when it precedes—New York State, the state of New York—unless the official name happens to take that form: the District of Columbia, the Dominion of Canada.

Caption style varies according to field, period, institution, and so on, and caption forms will of necessity vary from publication to publication, subject to subject. What follows is a sampling of formats; for specific instructions on individual elements of captions, see Collections and collectors/Credit lines, Dates, Dimensions, Inscriptions, Media of artworks, Titles of artworks.

The caption normally begins with information identifying and describing the work of art. It usually ends with collections data, often including fund or donor credit and, sometimes, accession number.

Line-for-line style places elements of the caption on separate lines with no punctuation at the end of each line; run-in style gives all the information sentence-style, separated by punctuation. Checklists and catalogue entries often employ the line-for-line style. This style is seldom used in most books that are not also exhibition catalogues and periodicals, where the elements are placed in sequential order separated by punctuation. (This style is often used in exhibition catalogues for captions to figure references.) The particular style that the publisher requires should be ascertained ahead of time by the author or editor if possible.

All or some of the following information may be included in an illustration caption, in the order given or in a slightly different order. (For more information about each of these categories, see under each item.)

In general, the artist’s name should be given in full even in multiple captions for the same artist’s work, unless the article or book is about a single artist, in which case the artist’s last name is sometimes used after the first mention or the artist’s name is omitted altogether.

William Wegman (b. 1943), Ray and Mrs. Lubner in Bed Watching T.V., 1981. Polacolor ER, 24 x 20 (61 x 50.8). University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography, Tucson [source: Whitney Museum of American Art]

Plate 1. Egyptian, Vessel in the Form of the God Bes, Late Period, ca. 600 B.C., faience. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Purchase in memory of Bernard V. Bothmer, The Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 94.110.

Colorplate 22. Henri Matisse. Le Luxe, 1907–8. Casein on canvas, 6’ 10 1/8” x 4’ 6 3/4” (205.3 x 139 cm). Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen; Rump Collection.

Catalogue entries and checklists include caption information, as above, usually on separate lines, often followed by provenance, exhibition history, and publication history. The format, like that for captions, will of necessity vary, and there is no one set way for all publications. Here, as in Captions, a sampling of formats is offered; for specific instructions on individual elements, see Collections and collectors/Credit lines, Dates, Dimensions, Exhibition history, Inscriptions, Media of artworks, Titles of artworks.

The format of entries for catalogues raisonnés closely follows that of the exhibition entry or checklist, with a number assigned to the work; title and variations of the title; date; medium (usually omitted if works of a single category are listed, such as all paintings, in which, for example, all works are oil on canvas unless noted otherwise); dimensions; inscriptions; collection; provenance; exhibition history; publication history; and a category, usually called “Remarks,” for other pertinent information. In a book with hundreds of such entries, it is important to verify consistency among entries. To this end, it is helpful to check each of the elements noted above one at a time from beginning to end. For specific instructions on individual elements, see Collections and collectors/Credit lines, Dates, Dimensions, Exhibition history, Inscriptions, Media of artworks, Titles of artworks.

Also called a biographical outline, a chronology is often included in artist monographs, solo exhibition catalogues, and catalogues raisonnés. Many formats are possible. In writing a chronology, it is important to decide on a particular approach and then use it consistently. It is also helpful to decide what kinds of information to include and exclude. If there is limited space, information readily at hand elsewhere in the volume (for example, in an exhibition history) as well as material of secondary importance may easily be omitted. The intention of a chronology is primarily to trace the artist’s development, not necessarily to list all of the artist’s accomplishments and activities.

Louis and his wife moved into Washington, where they purchased a house at 3833 Legation Street, N.W. Louis converted the 12-by-14-foot dining room into the studio he was to use for the rest of his life.

JANUARY 27: With Mme Matisse, departs for the first of two trips to Morocco. Mme Matisse will stay in Tangier until the end of March, Matisse until mid-April. Paints landscapes, including Periwinkles (pl. 147), having received a landscape commission from Ivan Morosov; still lifes, including Basket of Oranges (pl. 148); and figure paintings.

For classical works that exist in numerous editions, write out the names of the sections of the work in the note, as readers might use an edition different from yours. Example: (bk. 1, sec. 3). The elements in the text can subsequently be given in Arabic numerals separated by periods without writing out the names of the sections. Example: (1.5).

For museums, all information required by the institution should be cited. This may include accession number and date and such information as “the Jones fund,” “Gift of,” and “purchased with funds from.” Credit-line information, not to be confused with copyright information, identifies the donor or fund(s) through which the object was acquired. Some publishers change punctuation and capitalization for consistency in style, while others (especially museums) insist on using the form given by the museum, including punctuation and capitalization. Examples:

To help achieve consistency, it is permissible to omit the wording “courtesy” or “courtesy of” in the collection line. For example, if Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts specifies its credit line as “Courtesy, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,” it could be given as simply “Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.” The use of “courtesy” should be reserved for signaling the role of an intermediary in obtaining a photograph or permission, as in “Collection of the artist; courtesy Mary Boone Gallery, New York.”

Some museums require a copyright credit for having given permission to reproduce a photograph. This should appear in the photograph credit, not the credit line. Example:

States and countries should be given only for cities judged to be obscure or where there are two cities with the same name, for example, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Cambridge, England. By tradition, “Cambridge” is given for the city in England, whereas the state name is added for the city in Massachusetts. Names of states may be spelled out. If they are abbreviated, the standard Webster’sabbreviations should be used rather than postal abbreviations. Chicago 10.28 also lists the older abbreviations.

For private collections, only the information the collector provides should be given. Do not add a city to private collection unless the owner approves. Examples:

Note that in the text, while formal collections should be capitalized (Lehman Collection), generic terms associated with collections should be lowercased (the collection of Robert Lehman).

In general, names of foreign museums are given in the original language for scholarly publications. However, for books with a wide general audience, names of foreign museums may be anglicized. Examples:

In cases where the owner cannot be ascertained, use “Location unknown” or “Whereabouts unknown.” If it is known that a work has been destroyed or lost, that information should be provided. Examples:

Credits usually appear at the end of a book, after the index, if there is one, though if they are short they may be on the copyright page. Pictures, extensively quoted passages of text (short quoted passages—properly attributed in the text or endnotes—and extensive quotations in scholarly publications are still covered by fair use), photographers, and owners of rights (organizations such as SPADEM that own rights to an artist’s work but do not own the actual work of art) must all be credited scrupulously. Many owners of artworks now request that a credit line appear in the caption to an image. However, wherever permitted, information beyond the location and owner of an artwork should be removed from the caption and inserted into the credits page. Picture agencies and photographers often request that a credit line appear with a photograph. Many publishers do not generally consent to that style and instead place all such credits at the end of the book. Note that the credits typically are not listed in the table of contents. For specific instructions, see Photograph and illustration credits.

Decades: 1950s; 1840s and 1850s (in full, no punctuation); or, when the century referred to is unambiguous, “the thirties.” Do not vary formats within one sentence or paragraph. Use “in the 1950s and 1960s” or “in the fifties and sixties,” not “in the 1950s and sixties,” “in the 1950s and 60s,” or “in the 1950s and ’60s.”

For two-dimensional works of art, height precedes width; depth follows for three-dimensional works. Always compare the measurements against the photograph of the artwork to make sure that dimensions are given in the correct order. For example, if a picture is of an obviously horizontal artwork and this does not correspond to the order of the dimensions, check with the owner of the artwork; the measurements may be transposed, or there may be a typo in the numbers.

A lowercase x may be used for by, or a multiplication sign, but use only one or the other. Always use a word space on either side of the x. Editors should mark a lowercase x to be set as a multiplication sign (*).

Use the inch as the basic unit of measurement in captions and catalogue entries. Inches may be signified with the abbreviation in., used just once per set of dimensions: 17 x 19 in.; 106 x 27 x 8 in. It may also be indicated by inch marks. When foot and inch marks are used, repeat the mark in a set of dimensions: 6’ 2” x 12’ 10”. Editors should indicate the use of foot and inch marks for the designer/typesetter/printer, especially if quotation marks were used in the manuscript.

As a general rule, use only the half, quarter, and eighth fractions. Change all sixteenths and thirty-seconds to the nearest rounded fractions. (Some institutions, however, go down to sixteenths, especially for works on paper.) It is unacceptable to leave dimensions of a third inch, a fifth inch, or a tenth inch.

Website titles are given in roman without quotation marks and are capitalized headline style. Be sure that when referring to a Website, it is differentiated from print materials either by the title, name of sponsor, author, or by a short description. Use quotation marks for titled sections or “pages” within a Website. Website titles that correspond to books or articles can be styled accordingly. Give revision dates for pages that are continuously updated.

Cite blogs, named podcasts, and video blogs in a style similar to that used for periodical articles. Include the author of the post; the name of the post; the blog title or description; the name of the parent publication (if there is one); the date of posting; and the URL.

Various formats and devices can be used to download electronic books from a bookstore or library, including PDF e-book, Amazon Kindle, Kobo eReader, Microsoft Reader, and EPUB. They are identified at the end of a full citation. Example:

Books that have entered the public domain are often available online at no cost. The electronic format should always be given for the source of the text. A full bibliographic example:

To the extent possible, provide full publication details. Include medium information, such as the type of source (examples: podcast, video, DVD), length, and other relevant facts about the original source or performance. The electronic file name, or URL, should be included. Give the date last accessed if the source has no date. Note that electronic content with no formal publisher or sponsoring body has the status of unpublished work, but the copyright restrictions are the same as for any published material.

Most exhibition catalogues share a number of components particular to them. These may include, in order (more or less) from front to back: a list of the exhibition schedule—including the travel itinerary and the exhibition’s funders and sponsors—which often appears on the copyright page; the Contents page (in cases of multiple contributors to the catalogue entries, this may be the only place where the full names of authors who wrote catalogue entries are given); the sponsor’s statement; lenders to the exhibition (may also appear with the back matter); list of trustees; funders (often given on the copyright page); the director’s foreword; acknowledgments, usually listing all the people who contributed money, expertise, writing, or artwork; essay or essays; catalogue entries; chronology; bibliography (possibly including an exhibition history); and index.

The catalogue entries themselves have several components: catalogue number; artist, nationality, dates; title of work; where created, date; material/medium; dimensions; signature/inscription information; credit line; accession number; text; provenance, or ex coll.; bibliography, or references; exhibitions, or exhibited; condition; related works; remarks. If short forms are used for the elements of bibliography and exhibitions, then the full information will be found in the overall bibliography at the end of the catalogue. For specific instructions, see Catalogue entries and checklists, Chronology, Collections and collectors/Credit lines, Exhibition history, Inscriptions, Notes.

There are many ways to style an exhibition catalogue in notes, bibliography, and exhibition history. For purposes of notes and bibliography, the most important information is the publisher, which may be different from the venue. For exhibition histories, the venue is the essential information. It is possible, of course, to offer all of this information, but many formats are tailored to the purpose. Examples:

Ruth Butler, “Rodin and the Paris Salon,” in Rodin Rediscovered, ed. Albert E. Elsen [exh. cat., National Gallery of Art] (Washington, D.C., 1981), 21. [This separates the venue and publishing information.]

Elizabeth Cropper, Pietro Testa, exh. cat., Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Mass., 1988. [If publishing information is different, it may be added in parentheses.]

Miller, Lillian B., ed. The Peale Family. Exh. cat. New York: Abbeville Press in association with the Trust for Museum Exhibitions and the National Portrait Gallery, 1996.

This refers to two different elements: a listing of an artist’s exhibitions in an artist monograph or exhibition catalogue, usually preceding the bibliography; and an item in an exhibition catalogue entry listing all the venues where the object was displayed. The latter is also called “Exhibitions” or “Exhibited.”

The first type may take many forms. Most are divided into solo exhibitions (or one-artist shows) and group exhibitions, both arranged chronologically, from earliest to most recent. If opening and closing dates are used, exhibitions should be arranged chronologically by opening date. If only the year or years are used, then the exhibitions within each year may be arranged alphabetically by venue or by location. (The latter may be more sensible than trying to decide if Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum should be under S or G, and whether Mary Boone Gallery is under M or B. There is no set rule. However, it may not be helpful if many exhibitions took place in the same city.)

The listing of one-artist exhibitions may omit the titles of the exhibition, which usually consist only of the artist’s name; if the title is different, it may be included. Example:

For traveling exhibitions, the information may be indicated by the simple addition (traveled) at the end of the entry. Otherwise, all travel stops may be listed, usually after the opening venue, with just the year or the entire range of dates, so long as the same information is given for each item throughout. Some sample forms:

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation, September 4–November 17, 1989 (traveled to: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990).

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation, September 4–November 17, 1989. Traveled to: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (organizer), A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation (traveled to: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, September 4–November 17, 1989; Whitney Museum of American Art, December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990).

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation, September 4–November 17, 1989. Traveled to: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990 (organizer).

A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, September 4–November 17, 1989; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (organizer), December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (co-organizer), A Forest of Signs, September 4–November 17, 1989; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (co-organizer), December 15, 1989–January 12, 1990.

The element “Exhibitions” or “Exhibited” in an exhibition catalogue entry may also take many forms. It may give full exhibition information (venue, location, year, title, number, plate, or page numbers in the catalogue), or it may give shortened names, with full information found in the bibliography. A shortened name may give the location and year only. Examples:

Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, 1910, no. 114 or no. 117; Grand Central Art Galleries, New York, 1924, Retrospective Exhibition of Important Works of John Singer Sargent, no. 2, as The Lady with the Rose—My Sister;Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, 1950, The Adelaide Hilton de Groot Loan Collection, no cat.; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 1983, Painting in the South (trav. exh.), exh. cat. by D. R. Smith, pp. 48–50; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1987, American Paradise, exh. cat. by J. Howat et al., pp. 48–50, no. 120.

Every exhibiting institution has its own style for the identifying labels that appear with the objects displayed in its galleries. Essentially, they repeat the information given in the checklist or catalogue entry, often following the same or a similar format. Labels with text, sometimes called chats or didactics, usually follow the same rules as any other kind of text.

See Michael Kauffmann, “Typology—the Old Testament,” wall label for Rubens and the Bible, curated by Helen Braham, Courtauld Institute Galleries (Somerset House), London, 1990–93.

Some types of exhibitions, however—such as expositions, world’s fairs, or recurrent shows—are usually cited in roman type, upper- and lowercase, as for a title. Examples:

Extended quotations—the length varies, from more than fifty words to more than one hundred words to more than ten typed lines—are set off from the text with a line space above and below the quotation, indented one-half inch from the left margin, and double-spaced. Extracts should not be enclosed in quotation marks, and any quotations within them should be enclosed with double, not single, quotation marks. An extract placed before the text begins is known as an epigraph.

For cross-references to illustrations within the book, use a blind reference (see plate 00) and indicate in pencil, circled in the margin, the tentative illustration number or title referred to.

Foreign-language quotations are set out and punctuated in the same way as English-language quotations. If an English translation would be useful to readers, place it either before or after the original quotation. If avoiding clutter is desirable, place the original-language text in an endnote or footnote rather than in the text. If the author of the text has not provided the translation, the translator/source must be given. Foreign-language quotations should not be put in italics or underlined.

Capitalization of publication titles, in notes and bibliographies as well as in text: For the most part, adhere to the rules of sentence-style capitalization for the language in question—that is, capitalize the initial word of the title and subtitle and any words that would normally be capitalized in prose. An English translation can follow in parentheses. Example:

Foreign titles of artworks are capitalized in the same way as literary titles. In a title, any periods, guillemets (« »), or extra spaces can be changed to reflect standard use. When an artwork is best known by its foreign title, that title should appear first, with the English translation following in parentheses. Example:

However, titles of well-known foreign works should be given in English, with the original title (following in parentheses) when the writer thinks it worth including. Example:

Most institutions and publishers follow English-style capitalization for the names of foreign journals, buildings, institutions, and similar categories. Examples:

The use of foreign-language words in text should be minimized. Where it is essential, the English translation should be added within parentheses or quotation marks.

Foreign words and phrases that are likely to be unfamiliar should be in italics; translations following the foreign language are in parentheses, or quoted, but not both.

Traditional English names for foreign places should be used: Florence (not Firenze); Munich (not München). In general, publishers and institutions rely on the first-choice spelling given by Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary. Foreign publishers’ names are not translated. Example:

Omit honorifics except when thanking a person for help. In general, omit honorifics when citing debts of published or older sources; give honorifics when citing current unpublished ones, such as letters or oral communications. Examples:

To determine current usage for compound words and words with prefixes and suffixes, consultMerriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary or Webster’s Third New International Dictionary.Also, see the guidelines in Chicago 7.77–85. If a compound is not hyphenated in any of these sources, it probably should not be hyphenated. Use a hyphen only if the sentence might be ambiguous or confusing without it.

Hyphens are not used with most prefixes, such as non-,post-, orsemi-. Exceptions are before capitalized words, as in post-Kantian; to separate repeated vowels, as in semi-industrial; or to distinguish homonyms, as in re-creation/recreation. For a list of examples, see Chicago 7.85.

Most compounds with like are closed (that is, do not need a hyphen) unless confusion or misreading would result, for example, when the first element ends in the letter l, consists of three or more syllables, or is a compound word or a proper noun. Examples:

Note: A -like compound formed with a proper name (Matisse-like) is incorrect when the comparison is to the artist’s work or style, not the artist personally. In these instances, use Matissian, Disneyesque, Rousseauvian (or Rousseauesque)—or better yet, recast the sentence.

It is useful to employ italics in citing pages on which illustrations appear. For a large index, it might be helpful to use small capital letters for the names of artists or places. (Note that when using small caps for this purpose, full caps should be used for those letters that would normally be capitalized. Example: DE KOONING, WILLEM.)

Inscriptions of any type—signatures, labels, stamps, marks—are usually specified for artworks in the catalogue entry or checklist, transcribed word-for-word, line-for-line, along with their location. Letters or words lost through damage are usually indicated by empty brackets (one em space in length) or sometimes simply by a (one em) space. Parentheses indicate letters omitted as the result of abbreviation in the inscription. Words in capital letters are usually set in small capitals. Line divisions are indicated by a solidus/ (with a space—ideally, a hair space—on either side of the solidus). Note that full capital letters are used in the examples below. However, small capital letters may be advisable in some cases.

For sculpture, the following terms may be used to indicate locations: base or base top, base front, base rear, base side, rim of base, base edge, under base, side, corner, back, above base. Examples:

A full sentence or more in a foreign language should be set in roman type. Familiar words and phrases should be in roman type; such words are likely to be found in the latest edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. Common examples:

Each chapter should be a separate file.The front matter (table of contents, preface, acknowledgments, and foreword) takes up a single file, as does the back matter (appendix, glossary, bibliography, and image-reproduction credits). Complex and lengthy back-matter elements are better treated as separate files. Captions, too, should be in a separate file.

Footnotes and endnotes are placed in the same file as the relevant chapter.Notes in electronic manuscripts can be hyperlinked to the text by the publisher. When a publisher requests that footnotes or endnotes not be embedded in the text, it is sometimes helpful to create a separate file for them. One university press uses embedded notes in endnote function in both a text and a separate notes file, so that notes can be added or deleted as necessary. Note numbers in text should be superscript. In the notes themselves, note numbers should be on the line, not superscript.

All text elements must be fully double-spaced (not 1.5), including quotations, notes, bibliography, and captions, even if the computer program defaults to single spacing for notes and extracts.Such defaults can be overridden.

Tabs—never spaces—should be used for paragraph indents.Do not leave an extra line space between paragraphs unless instructed by the publisher to do so.

Use italic type or roman type underscored for words to be set in italics. Punctuation following italic words is set roman, including parentheses enclosing a word or words completely in italics.

Publishers’ instructions will vary on header and footer information in a manuscript. The author’s name, chapter number, and page number should appear in either the header or footer, unless the author has been instructed to keep the author’s name off the manuscript (for example, if it will be sent out for peer review).

name of the article/book; number of words for each element (text, footnotes, captions, etc.); total number of words, including notes, captions, and all other elements;

computer system used (PC, Macintosh), software and version (example: Microsoft Word 2010) or cloud-based application site (example: Google Docs), and the file names for all documents.

The medium of most artworks takes the form of “medium on support”: oil on canvas; pencil on wove paper (some institutions prefer “graphite” to “pencil”); pen and brown ink with brown wash on paper, and so on.

The materials used to create an object should be listed in a consistent fashion; both “tempera on wood” or “tempera on panel” are acceptable, but only one form should be used within a single publication. Similarly, if there are two different ways to cite the same medium (gelatin silver [or gelatin-silver] print and black-and-white photograph), just one should be used throughout.

Two terms are used for notes: footnotes, which are notes placed at the bottom of a page, and endnotes, which appear at the end of an article, chapter, or book. The terms footnotes and endnotes are essentially interchangeable.

Exhibition catalogues are indicated by the abbreviation “exh. cat.” Only the year the catalogue is published need be cited, not the exhibition’s range of dates. If the exhibition opened in one year and closed in the next, the opening date is used for the year of publication. Only the sponsoring institution need be given, not the entire list of venues. When the publisher is different from the sponsoring institution, that information may be (but need not be) included. Example: Lise Duclaux et al., Ingres, exh. cat., Petit Palais, Paris, 1967 (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1967). Note that some institutions substitute the publisher for the venue. Example: Lise Duclaux et al., Ingres, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1967). If the catalogue is cited as a book, that is, omitting the mention “exh. cat.,” then only the publisher’s name is needed. If the catalogue is a copublication between sponsoring institution and publisher, that information, as specified on the title page, should be given. Example: David B. Warren et al., American Decorative Arts and Paintings in the Bayou Bend Collection (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts in association with Princeton University Press, 1998).

Publishers’ names may be shortened to exclude “and Co.,” “Inc.,” “Ltd.,” “Publishers,” and the like, so long as they are treated consistently. Avoid truncating a publisher’s name: Alfred A. Knopf, not Knopf. For journals, if the month is included in the date of publication, spell it out or abbreviate it consistently. If seasons are used, uppercase them (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter).

For journals, distinguish between vol. and no. If the issue number is given, it is not necessary to give the month of publication (although it is not incorrect to include it). Example: Art Bulletin 81, no. 3 (1999). Unless the publication’s pages run consecutively throughout the volume, an issue number or month must be given.

Chicago recommends using figures only for volumes and page numbers. Example: (3: 466). Many institutions, however, prefer to identify one or each element. Example: vol. 3, 466, or vol. 3, p. 466.

A shortened form for references may be used to reduce the size of documentation. If there is a complete bibliography, the short form may be used even at the first mention. Example of a full citation in a note:

Use ibid. (not italicized) only in consecutive references (without intervening citations) to the same work. If note 3 contains two references and note 4 refers to the second reference cited in note 3, use a short form of the reference rather than ibid. in order to avoid ambiguity. Abbreviations for frequently cited journals, archives, series, and the like may be used in the notes if the key to the abbreviations is given at the head of the notes section or bibliography.

Vincent A. Smith, The Oxford History of India, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958). V. P. Shah, Jaina-Pupa-Mandana, vol. 1 (New Delhi: Abhinav, 1987), 90–105. [Note that for multivolume works, only the year of the volume cited need be given. If inclusive years are given, the year of the volume cited should be given as well.]

Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” in Minimalist Art: A Critical Anthology, ed. Gregory Battcock (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1968), 101–24. [Give inclusive pages for essays or chapters in a book.]

Pierre Marcel, “Une oeuvre de Watteau au musée de Dijon,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 94 (May 1904): 372–78. [For capitalization of foreign titles and periodicals, see Foreign languages.]

Numbers from one through one hundred and round numbers (six hundred, two thousand) are spelled out in text. Use numerals for numbers 101 and above, except for round numbers. Use numerals when numbers in the same paragraph range both below and above one hundred. Use numerals when odd numbers over one hundred are mixed with round numbers. Examples:

Inclusive numbers: Use all digits for numbers below 100 (that is, all two-digit numbers). Use all digits when the first number ends with 00. Use the changed part only, omitting unneeded zeroes from 101 through 109, 201 through 209, etc. For B.C. dates, repeat all digits. All digits are usually given for birth and death dates as well. For all other dates, repeat the last two digits only. For inclusive page numbers and other uses, repeat the last two digits only. Examples:

Arabic numerals are used for series, volume, part, section, or chapter numbers, even if roman numerals are given in the cited source. Roman numerals (lowercased) are used only for front-matter pages and illustrations/plates so numbered.

For a list of useful Internet resources, click on Helpful Links. Suggestions for additional Web resources are always welcome, as is feedback on the present set of links. Send e-mails to philfreshman@gmail.com.

It is usually the author’s responsibility to obtain written permission to reproduce images of any kind. This may include permission from the owner of a work of art, from a photographer for his or her photograph of a work of art, from a photo agency, from the artist or artist’s agent, from an institution that holds copyright to the object or the image, or from others. Publishers may require that editors make sure all necessary permissions have been obtained and that any required credit form has been supplied.

Some books list such credits page by page, a method that takes up a great deal of space. A more usual procedure is to make a list in alphabetical order, giving the name of the photographer, institution, or agency followed by page numbers and directionals (top, above, center, below, bottom, left, right) to specify the illustration when more than one appears on a single page. If directionals are abbreviated, a key should be given. The names and pages may be given in list form or run in, separated by semicolons.

It is usually unnecessary to credit the museum or collection that owns the artwork as the supplier of the reproduction, unless the institution requires a special form of credit. Example: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. [credit line for owner of artwork] (photo: © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art). A credit usually must be given if the photo was supplied by a photograph archive or agency or by an institution other than the owner or if the photographer’s name is required. Examples:

If the illustration was reproduced from a book, that information must be given, with the full facts of publication and the page and/or plate number. Example: (from Spiro Kostof, A History of Architecture [New York: Oxford University Press, 1985], p. 195, fig. 9.4.)

Publishers generally request that photographic material and artwork be submitted in digital formats. They will recommend their preferred types of art files, and will need to know details of the software programs the author has used.

At the place in the text where an image is to be inserted, an electronic work may display a thumbnail image, along with its file name and the hyperlink to the file of the full-size image. Placement references (example: ) may be unnecessary, as a software program may have its own keying system for illustrations.

Digital works in the public domain may be used without permission—with the owner acknowledged, as a courtesy, in the article/book—but the quality of Internet pictures or artwork created using the Microsoft Office suite may be too poor for use in a publication.

Electronic transmission is quickly becoming the preferred mode for submitting photographic material and artwork, but in some cases actual photographs, transparencies, and the like are acceptable.

Authors are usually responsible for obtaining photographs and transparencies and for obtaining permissions to reproduce them. Usually, authors pay for their own photographs. The question of who pays reproduction fees depends on the publisher. For journal articles, the author is in almost all cases responsible for this. For books and exhibition catalogues, however, the publisher may pay some or all of the reproduction fees. Many museums will waive reproduction fees for photographs to be used in scholarly periodicals.

Generally, photographs must be in hand when an article/book is submitted for publication. If illustrations need to be scanned, publishers usually prefer to do this themselves in order to ensure quality control. If you do not have a photograph of a particular artwork and want to wait to order the photograph until after publication decisions are made, you may be able to include a photocopy made from a book or other publication.

Marking should be done on a separate label. Write on adhesive labels before attaching them. Attach the identification label on a pressure-sensitive sticker or label to the back of the black-and-white photograph, to the plastic sleeve covering the transparency, or directly to the slide mount. If it is necessary to write directly on the back of photos, it should be done lightly with a soft-lead (no. 1) pencil. Hard pencils and ballpoint pens can ruin the surface of the photograph, whereas felt-tip pens can bleed or, if used on a group of photographs that are then stacked, transfer to the photographic surface underneath it. Do not use paper clips, staples, rubber bands, or other plastic or metal fasteners on or in contact with photographs. Never use Scotch tape on photographs—front or back.

If only part of the illustration is required, the area to be reproduced should be clearly indicated on a photocopy or printout of the photograph. If the image contains writing, such as a caption in a print, indicate if the writing should be cropped out or if it is essential to retain the writing. If color transparencies are to be printed in black-and-white, or if a print needs to be cropped, silhouetted, touched up, or cleaned, that information should be noted on the envelopes enclosing them and/or on an illustration or photo list supplied with the illustrations.

The submission of illustrations should be accompanied by an illustration or caption list, sometimes called a photo log or illustration-transmittal list, with numbers corresponding to the identification numbers on the illustrations. The desired size of each illustration should be indicated (large, medium, small; A, B, C; full page, half page, quarter page), those to be reproduced in color so marked, and any illustrations that belong together noted, as well as any other instructions for the designer, such as cropping, silhouetting, converting from color to black-and-white, touching up, cleaning, or making a detail. It may be useful to note the format of the illustration submitted (b/w, transparency, slide, and so on), as this information is essential for the production list, which will contain all the above information with final numbers and the final order of all illustrations being used.

Use a singular possessive for animal adjectives (examples: lion’s-head decoration; bull’s-eye window) and entities such as corporations and organizations, except when the name is a plural form ending in s(example: Springboard for the Arts’ workshop).

Depending on the publisher and the schedule, an author may be involved in several rounds of editing before a manuscript is finalized—and is responsible for carefully proofreading the agreed-upon finished edit. The author should be permitted to read the first set of page proofs in order to fix gross errors but should not be permitted to rewrite on proofs, and can be charged for corrections that the publisher deems excessive. The standard correction allowance before charges are applied is 10 percent.

Use a comma before which when it introduces a nonrestrictive clause (one that adds information but that if omitted would not change the meaning

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey