lcd monitors compatible with mac iici for sale

A vintage Apple monitor isn"t just a blast from the past to add to your Mac collection, but it can also be used for retro computing. Apple has been producing computer monitors since 1976 in varying sizes and capabilities. If you plan on using a vintage Apple monitor, then you should first learn about the display capabilities and required connections to ensure proper functioning of your iMac.

Apple first started producing monochrome monitors and then eventually moved onto cathode ray tube (CRT) and liquid crystal display (LCD) options. Apple nicknamed monochrome monitors "Green Screens" due to the bright green text color on their screens. These original devices were bulky and lacked color capabilities in their resolutions, making them fade out of popularity towards the 1980"s. CRT displays are also heavy, but they offered more colors and a higher-quality display. Apple used these monitors until the late 1990"s when LCD monitors took over the market.

LCD technology uses a flat panel screen, rather than the bulky screens of CTR standards. Today LCD monitors are the standard screen for laptops and desktops almost exclusively, and they began to outsell CTRs by 2004.

The earliest monitors were very small. Most monitors only measured 13-14 inches. However, in the 1990"s and early 2000"s, larger LCD monitor sizes became more popular. Monitor sizes up to 30 inches are common, but the most-used option is the 27-inch display. This size creates a resolution that is suitable for daily Mac use as well as gaming and entertainment purposes.

Apple Macbooks and iMac models are designed with portability and ease of use in mind. Mac never produced a model over 17 inches as a result. Most displays found in Apple Macbook products utilize Retina technology, which is a type of LED format that offers higher pixel density. The most common Mac sizes include the following:

The page is written in German language. It seems to be maintained, still, as the page moved to a new host few months ago (thanks to Uwe Draeger !). If one knows about a similar collection of well documented mac hardware hacks in English language, please post the url.

If you want to set up a monitor for old mac use, only, it is a good idea to make a cable with the appropriate connector and hard wired sense pins, as additional adaptors tend to distort the analogue video signal slightly. It is also possible to make the mac video card ignore any sense pin settings and to choose from any resolution the video card is capable of. To make this, use some control panel like "Activate all resolutions". In case you did so, consider to make a sense pin wiring for a basic resolution of 640 x 480 at 66.7 Hz to support almost any mac w/o specific software settings.

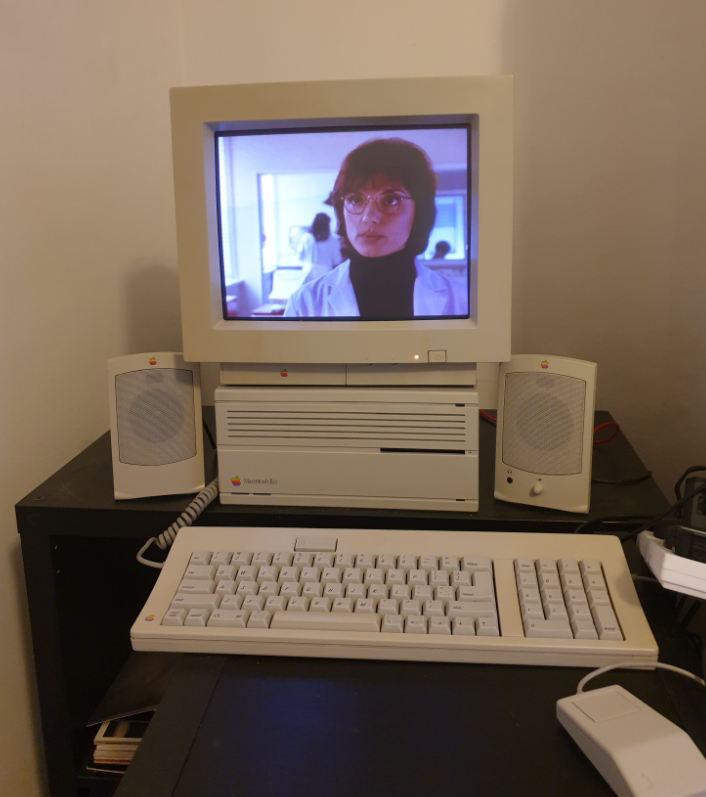

Building on the success of the Mac IIcx, the IIci offers 56% more power in the same compact case. A new feature was integrated video. The big advantage: Users no longer needed to buy a separate video card. The big disadvantage: The built-in video uses system memory (this is sometimes called “vampire video”).

Built-in video replaces the Macintosh II High Resolution Video Card (25 MHz motherboard video vs. a 10 MHz NuBus connection) and supports 8-bit color on a 640 x 480 screen as well as 4-bits on a 640 x 870 Portrait Display. Depending on bit depth, this uses between 32 KB and 320 KB of system memory. Also, Byte reports (Oct. 1989) that because the CPU and video share the same memory, the CPU is shut out of accessing RAM during video refresh, reducing performance by up to 8%.

Our own tests on a IIci show that although CPU performance does increase slightly when using a NuBus video card, video performance with an unaccelerated video card is about half as fast as the built-in video. Unless you need to support a larger screen or have an accelerated video card, overall performance may be worse with a video card than with internal video.

The Mac II, IIx, and IIcx all run a 16 MHz CPU on a 16 MHz motherboard with a separate 10 MHz bus for NuBus cards. Byte mentions (Oct. 1989) that the IIci runs its CPU and RAM at 25 MHz, NuBus at 10 MHz, I/O subsystems with a third oscillator, and onboard video with a fourth oscillator. By decoupling various subsystems this way, it was easier for Apple to boost the CPU and RAM speed without redesigning every part of the motherboard.

The IIci was the first Mac to support the 68030’s burst access mode, which “allows the CPU to read 16 bytes of data at a time in about half the clock cycles. This results in [a] . . . 10 percent improvement in performance.” (Byte, Oct. 1989, p. 102)

The IIci was the first Mac with “clean” ROMs, allowing 32-bit operation without special software. Along with the Mac Portable, it was the first Mac to use surface mount technology.

If you’re running low on RAM, by all means buy more. You should have at least 8 MB, but more is much better (unless you’re sticking with System 6, in which case you can’t use more than 8 MB).

Quadra 700 motherboards are uncommon. For that level of performance, consider a 68040-based accelerator, such as the Sonnet Presto 040 (40 MHz 68040 with 128 KB L2 cache, see our benchmark page). See a more complete list of accelerators below. Note that you will have to perform surgery on your case with the Quadra 700 motherboard upgrade.

A newer hard drive will be far more responsive and have far more capacity than the one that shipped with the computer. Any 3.5″ half-height or third-height drive will fit.

Discontinued accelerators (68030 unless otherwise noted) include the Applied Engineering TransWarp (50 MHz 68030, 25, 33 MHz 68040), DayStar Universal PowerCache (33, 40, 50 MHz), Fusion Data TokaMac SX (25 MHz 68040), Logica LogiCache (50 MHz), Radius Rocket (25 MHz 68LC040 to 40 MHz 68040), TechWorks NuBus (33 MHz 68040), and Total Systems Magellan (25 MHz 68040).

Moving Files from Your New Mac to Your Vintage Mac, Paul Brierley, The ‘Book Beat, 2006.06.13. Old Macs use floppies; new ones don’t. Old Macs use AppleTalk; Tiger doesn’t support it. New Macs can burn CDs, but old CD drives can’t always read CD-R. So how do you move the files?

Was the Macintosh IIci the Best Mac Ever?, Dan Knight, Mac Musings, 2009.01.19. Introduced in 1989, the Mac IIci was fast, had integrated video, included 3 expansion slots, and could be upgraded in myriad ways.

Know Your Mac’s Upgrade Options, Phil Herlihy, The Usefulness Equation, 2008.08.26. Any Mac can be upgraded, but it’s a question of what can be upgraded – RAM, hard drive, video, CPU – and how far it can be upgraded.

Creating Classic Mac Boot Floppies in OS X, Paul Brierley, The ‘Book Beat, 2008.08.07. Yes, it is possible to create a boot floppy for the Classic Mac OS using an OS X Mac that doesn’t have Classic. Here’s how.

The Compressed Air Keyboard Repair, Charles W Moore, Miscellaneous Ramblings, 2008.07.24. If your keyboard isn’t working as well as it once did, blasting under the keys with compressed air may be the cure.

A Vintage Mac Network Can Be as Useful as a Modern One, Carl Nygren, My Turn, 2008.04.08. Old Macs can exchange data and share an Internet connection very nicely using Apple’s old LocalTalk networking.

Vintage Mac Networking and File Exchange, Adam Rosen, Adam’s Apple, 2007.12.19. How to network vintage Macs with modern Macs and tips on exchanging files using floppies, Zip disks, and other media.

Vintage Mac Video and Monitor Mania, Adam Rosen, Adam’s Apple, 2007.12.17. Vintage Macs and monitors didn’t use VGA connectors. Tips on making modern monitors work with old Macs.

Getting Inside Vintage Macs and Swapping Out Bad Parts, Adam Rosen, Adam’s Apple, 2007.12.14. When an old Mac dies, the best source of parts is usually another dead Mac with different failed parts.

Solving Mac Startup Problems, Adam Rosen, Adam’s Apple, 2007.12.12. When your old Mac won’t boot, the most likely culprits are a dead PRAM battery or a failed (or failing) hard drive.

20 year old Mac IIci dies, Mozilla for Classic Mac OS, USB 3 on Mac this year?, and more, Mac News Review, 2009.07.10. Also picking a Mac over a PC, which Macs can boot from SD?, GrandReporter automates searching the Web, an online image editor, and more.

The 25 most important Macs (part 2), Dan Knight, Mac Musings, 2009.02.17. The 25 most significant Macs in the first 25 years of the platform, continued.

Golden Apples: The 25 best Macs to date, Michelle Klein-Häss, Geek Speak, 2009.01.27. The best Macs from 1984 through 2009, including a couple that aren’t technically Macs.

Why You Should Partition Your Mac’s Hard Drive, Dan Knight, Mac Musings, 2008.12.11. “At the very least, it makes sense to have a second partition with a bootable version of the Mac OS, so if you have problems with your work partition, you can boot from the ’emergency’ partition to run Disk Utility and other diagnostics.”

Better and Safer Surfing with Internet Explorer and the Classic Mac OS, Max Wallgren, Mac Daniel, 2007.11.06. Tips on which browsers work best with different Mac OS versions plus extra software to clean cookies and caches, detect viruses, handle downloads, etc.

Simple Macs for Simple Tasks, Tommy Thomas, Welcome to Macintosh, 2007.10.19. Long live 680×0 Macs and the classic Mac OS. For simple tasks such as writing, they can provide a great, low distraction environment.

Interchangeabilty and Compatibility of Apple 1.4 MB Floppy SuperDrives, Sonic Purity, Mac Daniel, 2007.09.26. Apple used two kinds of high-density floppy drives on Macs, auto-inject and manual inject. Can they be swapped?

Macintosh IIx: Apple’s flagship gains a better CPU, FPU, and floppy drive, Dan Knight, Mac Musings, 2007.09.19. 20 years ago Apple improved the Mac II by using a Motorola 68030 CPU with the new 68882 FPU. And to top it off, the IIx was the first Mac that could read DOS disks with its internal drive.

Vintage Macs provide a less distracting writing environment, Brian Richards, Advantage Mac, 2007.09.18. A Mac OS X user finds an old Macintosh IIsi and discovers the joy of writing undisturbed by music, messaging, and streaming content.

No junk from Apple, Mac mouse dies after 18 years, time to cut the gigabyte BS, and more, Mac News Review, 2007.08.10. Also new iMac and Mac mini models, Apple’s aluminum keyboards, new NAS drive looks like a Mac mini, first software update for aluminum iMacs, and more.

Mac System 7.5.5 Can Do Anything Mac OS 7.6.1 Can, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2007.06.04. Yes, it is possible to run Internet Explorer 5.1.7 and SoundJam with System 7.5.5. You just need to have all the updates – and make one modification for SoundJam.

Appearance Manager Allows Internet Explorer 5.1.7 to Work with Mac OS 7.6.1, Max Wallgren, Mac Daniel, 2007.05.23. Want a fairly modern browser with an old, fast operating system? Mac OS 7.6.1 plus the Appearance Manager and Internet Explorer may be just what you want.

Format Any Drive for Older Macs with Patched Apple Tools, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2007.04.25. Apple HD SC Setup and Drive Setup only work with Apple branded hard drives – until you apply the patches linked to this article.

Making floppies and CDs for older Macs using modern Macs, Windows, and Linux PCs, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2007.03.15. Older Macs use HFS floppies and CDs. Here are the free resources you’ll need to write floppies or CDs for vintage Macs using your modern computer.

System 7 Today, advocates of Apple’s ‘orphan’ Mac OS 7.6.1, Tommy Thomas, Welcome to Macintosh, 2006.10.26. Why Mac OS 7.6.1 is far better for 68040 and PowerPC Macs than System 7.5.x.

The legendary Apple Extended Keyboard, Tommy Thomas, Welcome to Macintosh, 2006.10.13. Introduced in 1987, this extended keyboard was well designed and very solidly built. It remains a favorite of long-time Mac users.

30 days of old school computing: No real hardships, Ted Hodges, Vintage Mac Living, 2006.10.11. These old black-and-white Macs are just fine for messaging, word processing, spreadsheets, scheduling, contact management, and browsing the Web.

Jag’s House, where older Macs still rock, Tommy Thomas, Welcome to Macintosh, 2006.09.25. Over a decade old, Jag’s House is the oldest Mac website supporting classic Macs and remains a great resource for vintage Mac users.

Mac OS 8 and 8.1: Maximum Size, Maximum Convenience, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2006.09.11. Mac OS 8 and 8.1 add some useful new features and tools, and it can even be practical on 68030-based Macs.

Vintage Macs with System 6 run circles around 3 GHz Windows 2000 PC, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2006.07.06. Which grows faster, hardware speed or software bloat? These benchmarks show vintage Macs let you be productive much more quickly than modern Windows PCs.

Floppy drive observations: A compleat guide to Mac floppy drives and disk formats, Scott Baret, Online Tech Journal, 2006.06.29. A history of the Mac floppy from the 400K drive in the Mac 128K through the manual-inject 1.4M SuperDrives used in the late 1990s.

System 7.6.1 is perfect for many older Macs, John Martorana, That Old Mac Magic, 2006.03.24. Want the best speed from your old Mac? System 7.6.1 can give you that with a fairly small memory footprint – also helpful on older Macs.

System 7.5 and Mac OS 7.6: The beginning and end of an era, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2006.02.15. System 7.5 and Mac OS 7.6 introduced many new features and greater modernity while staying within reach of most early Macintosh models.

Turning an LC or other ancient Mac into a webcam with a QuickCam, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2006.01.25. As long as it has 4 MB of RAM and a hard drive, any 16 MHz or faster Mac that supports color can be configured as a webcam.

System 7: Bigger, better, more expandable, and a bit slower than System 6, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2006.01.04. The early versions of System 7 provide broader capability for modern tasks than System 6 while still being practical for even the lowliest Macs.

Web browser tips for the classic Mac OS, Nathan Thompson, Embracing Obsolescence, 2006.01.03. Tips on getting the most out of WaMCom, Mozilla, Internet Explorer, iCab, Opera, and WannaBe using the classic Mac OS.

Which system software is best for my vintage Mac?, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2005.11.22. Which system software works best depends to a great extent on just which Mac you have and how much RAM is installed.

The legendary DayStar Turbo 040 hot rods 68030 Macs, Tyler Sable, Classic Restorations, 2005.11.29. DayStar’s vintage upgrade can make an SE/30 and most models in the Mac II series faster than the ‘wicked fast’ Mac IIfx.

Never connect an Apple II 5.25″ floppy drive to the Mac’s floppy port. Doing so can ruin the floppy controller, meaning you can’t even use the internal drive any longer.

Internal video on the IIci and IIsi, and the Mac II mono and color video cards, will not work with multisync monitors, whether Apple or PC style. Griffin Technology made the Mac 2 Series Adapter, which works with Apple’s Multiple Scan monitors and most Mac compatible monitors. There was also a version for using VGA-type monitors on older Macs.

Serial port normally restricted to 57.6 kbps; throughput with a 56k modem may be limited. See 56k modem page. For more information on Mac serial ports, read Macintosh Serial Throughput in our Online Tech Journal.

In January 1989 – January has always been one of Apple’s favorite months for new product releases – Apple unveiled the best ever compact Mac with a 9″ b&w display, the Macintosh SE/30.

Essentially a Mac IIx in an SE case with a single expansion slot, the SE/30 with an ethernet card became a favorite network server, since it didn’t require buying a video card and monitor like the IIx did.

In March, Apple introduced two very practical monitors for professionals, the Portrait Display, which showed a full page at once, and the Two-Page Display, a 21″ screen that showed two pages side-by-side. Both were high quality b&w screens, many of which remained in use for a decade or more.

Apple didn’t stop there – six months later it shipped the Mac IIci, the first Mac to run faster than 16 MHz. Not only did the IIci run at a blazing 25 MHz, but by adding a 32 KB level 2 cache card, you could boost performance another 30%, making it about twice as fast as 16 MHz Macs.

The IIci was also the first modular Mac with integrated video. Using system memory, the IIci supports a 640 x 480 display at 256 colors or a Portrait Display with 16 shades of gray.

Of course, there were compromises involved with this design. Since video runs at 25 MHz, it is very fast, but because it uses system memory, other processes were slowed by about 8%. To overcome this, many users installed NuBus video cards (accelerated ones when they became available), allowing all system memory to be used just for programs, not sharing some of it for video.

The IIci had the best SCSI throughput of any 60830-based Mac, hitting approximately 2.1 MBps, compared with 1.4 MBps for earlier models. Even the “wicked fast” 40 MHz IIfx introduced in 1990 had slower SCSI.

I used a IIci for several years, designing books on an Apple Two-Page Display. Although a powerhouse in its day, I was glad to move on to Quadras and Power Macs in later years. Of course, desktop publishing is one of those areas that drove the Mac market and never had enough speed.

I also own a couple Portables, both work but need to be cleaned up. One has 5 MB of RAM, and I used to tote it around, claiming it was my Macintosh Gameboy. It handles System 7.x quite nicely.

Sometime between 2003 and 2006 I found this Apple Macintosh Quadra 700 at the old State Road Goodwill in Cuyahoga Falls. According to this Macintosh serial decoding site my Quadra (serial # F114628QC82) was the 7012th Mac built in the 14th week of 1991 in Apple’s Fremont, California factory.

After I started this blog I dragged over most of the vintage Mac stuff out of my parents’ attic to my apartment. I decided that the Quadra 700 should get a semi-permanent place on my vintage computing desk. The desk (which you’ve probably seen in the Macintosh SE and PowerBook G3 entries) has a credenza that limits how deep of a monitor I can use. The Multiple Scan 17 doesn’t leave enough space for the keyboard and really restricts what else I can have on the desk.

Originally my plan was to use the Quadra with an HP 1740 LCD monitor I picked up at the Kent-Ravena Goodwill so I bought a DB-15 to HD-15 (VGA) converter.

However, while digging through the Mac stuff in my parents’ attic I made an interesting discovery. Unbeknownst to me I owned AppleColor High-Resolution RGB 13″ monitor.

When I was still living with my parents there wasn’t really a lot of room in my bedroom for all of the vintage computing stuff I had accumulated. Often, I would lose interest in something and it would go into the attic.

At some point my Dad must have brought home this monitor from a thrift store. Unlike most CRT monitors where the monitor cable is attached to the monitor this one has a detachable cable which was lost when he bought it (I have since purchased a replacement on eBay). With all of the Mac stuff put away and no monitor cable to test it with, it joined everything else in the attic and I forgot about it.

Years later when I stumbled upon it deep in the shadows of a poorly lit part of the room, I thought it was the cheaper Macintosh 12″ RGB monitor that went with the LC series. But then, I saw the name plate on the back.

This was an amazing stroke of luck because that’s a damn fine monitor. Back in the late 80s this was one of Apple’s high end Trinitron monitors. Remember those Apple brochures my mother got in West Akron in 1989 from the Macintosh SE entry?

Apple also sold a rather attractive optional base for the AppleColor RGB monitor with great Snow White detailing, as seen in this drawing from Technical Introduction to the Macintosh Family: Second Edition.

Oddly enough, when I ventured further into my parent’s attic I found a box of Macintosh stuff that a college roommate had recovered from being trashed at a college graphics lab that contained, among other things, the manual for this model of monitor.

The Quadra 700 is one of my all-time favorite thrift store finds. It was the first extremely serious Macintosh I have owned from the expandable 680X0 era (roughly from 1987 to 1994 when Apple moved to PowerPC CPUs). Previously the most powerful Mac I had found was a Macintosh LC III with a color monitor. That machine introduced me to what the experience of using a color Macintosh had been like in the early 1990s but the Quadra was on another level entirely.

To put this in perspective: Macintosh LC III was a lower-end machine from 1993 that gave you something like the performance of a high-end Macintosh from 1989. The Quadra 700 (along with the Quadra 900 which was basically the same guts in a larger, more expandable case) was Apple’s late 1991 high-end machine. When it was new, the Quadra 700 cost a staggering $5700, without a monitor. The monitor could easily add another $1500.

Apple created a lot of machines in the Macintosh II series and it’s a bit difficult to keep track of them. As you can see in the brochure, the original machine was the Macintosh II, built around Motorola’s 68020 processor and for the first time in the Macintosh, a fully 32-bit bus. That machine was succeeded the following year by the Macintosh IIx, which, like all following Macintosh II models used the 68030 processor. The II and the IIx both had six NuBus expansion slots, which is why their cases are so wide.

If you’re more familiar with the history of Intel processors don’t let the similar numbering schemes lead you into thinking the 68020 was equivalent to a 286 and the 68030 was equivalent to a 386. In reality the original Macintosh’s 68000 CPU would be more comparable to the 286 while the 68020 and 68030 were comparable to the 386. In the numbering scheme that Motorola was using at the time processors with even numbered digits in their second to last number like the 68000, 68020 and 68040 were new designs and processors with odd numbers like 68010 and 68030 were enhancements to the previous model. The 68030 gained a memory mapping unit (MMU) which enabled virtual memory. The jump from the 286 to the 386 was much greater than the jump from the 68020 to the 68030.

The next machine in the series was the Macintosh IIcx in 1989, which basically took the guts of the IIx and put them in a smaller case with only three expansion slots (hence, it’s a II-compact-x). Like the II and the IIx, the IIcx had no on-board video and required a video card to be in one of the expansion slots.

The case used in the Macintosh IIcx and IIci was designed to match in color, styling, and size the AppleColor High Resolution RGB monitor I have, as seen in this illustration from Technical Introduction to the Macintosh Family: Second Edition.

As you probably caught onto by now the Quadra 700 uses the same case as the Macintosh IIci but with the Snow White detail lines and the Apple badge turned 90 degrees, turning it into a mini-tower. That’s why the monitor matches the Quadra so well.

The last Macintosh to use the full-sized six-slot Macintosh II case was the uber-expensive Macintosh IIfx in 1990. It used a blistering 40MHz 68030 and started at $8970.

However, if you bought a IIfx, you may have felt very silly the next year when the Quadra series based on the new 68040 processor came out and succeeded the Macintosh II series.

According to these benchmarks at Low End Mac, the 25MHz 68040 in the Quadra 700 scores 33% higher than the Macintosh IIfx’s 40MHz 68030 on an integer benchmark and five times as fast on a math benchmark. Plus, it was just over half the price of the IIfx.

The interior of the Quadra 700 is extremely tidy. The question the hardware designers at Apple were clearly working with was: what is the most efficient case layout if you need to pack a power supply, a hard disk, 3.5″ floppy drive, and 2 full-length expansion slots in a case? In the Quadra 700 the two drives are at the front of the right side of the case, the PSU is at the back of the right side, and the two expansion slots take up the left side of the case.

You can tell how the arrival of CD-ROM drives threw a wrench in all of this serene order. You’re never going to shoe-horn a 5.25″ optical drive in this case. And when you do get a CD drive in the case you’re going to have an ugly looking gap for the drive door rather than just the understated slot for the floppy. I think Apple’s designs lost a lot of their minimalist beauty when they started putting CD drives in Macintoshes soon after the Quadra 700.

Inside the case, the way everything is attached without screws is very impressive. The sides of the case and the cage that hold the drives forms a channel that the PSU slides into. Assuming nothing is stuck you should be able to pull out the PSU, detach the drive cables, and then pull out the drive cage in a few short minutes without using a screwdriver (actually, there’s supposed to be a screw securing the drive cage to the logic board but it was missing in mine with no ill effects).

We tend to think of plastic in the pejorative. But, plastic is only cheap and flimsy when it’s badly done. This Quadra’s case is plastic done really, really well. It doesn’t flex or bend. It’s rock solid. But, when you pick the machine up it’s much lighter than you expect it to be.

Second, notice the six empty RAM slots. Curiously enough, on the Quadra 700 the shorter memory slots just above the battery are the main RAM. I believe this machine has four 4MB SIMMs in addition to 4MB RAM soldered onto the logic board (the neat horizontal row of chips labeled DRAM to the left of the SIMMs on the bottom of the picture) The larger white empty slots are for VRAM expansion.

The way the video hardware talks to the CPU makes it really, really fast compared to previous Macintoshes with built-in video and even expensive video cards for the Macintosh II series.

The Quadra’s video hardware supports a wide variety of common resolutions and refresh rates including VGA’s 640×480 and SVGA’s 800×600. That’s why I can use the Quadra with that VGA adapter pictured above. This was neat stuff in an era when Macintoshes tended to be very proprietary.

Imagine a time when computing was quickly becoming mainstream; computers with graphical user interfaces were becoming the norm, and expensive Macs were not doing entirely well in the market. Early Windows-based computers were obtrusive, buggy, and required more time setting IRQs and swapping hard drive ribbon cables than they offered uninterrupted uptime.

After growing up with a three or four of computers thrown together with scrap parts and running whatever operating systems I could pull together from a friend or my Dad’s office, I was longing for a computer on which I could simply work, play, and have some fun. I had enjoyed the feeling of touching the components of the computer that made sensible words and graphics appear on the screen, but I often didn’t enjoy the fact that I had to do it (especially when I gave myself a nice shock one time!).

In 1992, my Dad helped me buy a Mac; our family had a Mac Plus for a time, and I had learned to love early black and white games like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and classics like Spectre or Armor Alley.

I quickly dove into the case, and realized what an immense pleasure it was to operate inside the IIci; getting to the orderly insides took only a click and a pop of two little latches on the back of the top panel. Until I bought a Blue-and-White G3, I thought the IIci was the hardware-hacker’s ideal Mac.

I booted up the Mac and installed Mac OS 7.5.3 over our in-house AppleTalk network (this definitely beat swapping out 19 floppy disks, though the transfer rate was still abysmal—about 200kbps). I started finding any shareware floppies my Dad or brother had (my brother had some cutting-edge games like Pathways Into Darkness or Out of this World and the classic Dark Castle), and loading them on the (then) roomy 80 MB SCSI hard drive.

I really appreciated the integration of the Mac OS and the hardware of the IIci; when I decided to upgrade the RAM to 8 MB (from the original 2 MB), the Mac booted and was happy, and ran Photoshop LE 2.5.1 better than ever. When I installed a NuBus 10baseT network card (so I could use my Dad’s newly-installed network to access his ISDN connection to the Internet), I didn’t have to think about IRQ settings, the slot into which I installed the card, etc. In fact, I’d never spent more than a minute or two installing any of the upgrades I eventually put in my IIci:

I used this Mac IIci for over three years, making it the Mac I’ve used and owned the longest. I loved the simple, minimalist design so much that I decided to strip the innards and set the Mac on my dresser in lieu of other art objects until I left my parents’ house for College.

This Mac helped teach me all the paradigms of the Mac OS graphical environment (in comparison to MS DOS’s command line, and Windows 3.x and 95/98), and taught me that there was more to computing than flicking tiny switches on daughter cards, swapping out drive cables, and replacing bad CD-ROM drives (a common occurrence on the cheap PCs I was used to building). I likely spent a hundred hours simply memorizing every system setting, experimenting with the speed of a RAM disk, and playing with Photoshop, Glider Pro, Claris Works, etc.

I built my first website on this Mac IIci; it was little more than one page with a few facts about my life and family and some of my favorite pictures (scanned in with a Microtek SCSI scanner which took about 5 minutes per scan). I used Claris Home Page, but tweaked the HTML output by hand in SimpleText. I hosted the website on a Whistle InterJet that my Dad had running on a public IP address at his office.

Now that I’m a full-time web developer working in 5+ programming languages, I appreciate the simple setup I used to learn the basics of the web: HTML, JavaScript, and the HTTP protocol, all through plain text editing in SimpleText on a Mac. I truly believe that using a simple Mac helped me to focus more on the content and design of my work, even when working on parts of my projects that would rarely be seen by users. Though Steve Jobs wasn’t at Apple when the IIci was built, I think his design principles were still having a positive influence on the hardware designs coming out of Cupertino.

I wish I still had a IIci around, simply so I could pull all the parts off again and put it back together—there was something therapeutic about being able to strip an entire computer down to it’s casing (revealing signatures of the computer’s design team) and put it back together in less than 5 minutes. I credit a lot of my fundamental computer architecture understanding to the fact that I could pick apart every component of the computer—down to the CPU itself—and view the pins and jumper switches that controlled certain settings that affected how the software on the computer would run.

Looking back on the IIci and another favorite, the PowerBook 180c (a laptop with tricky Torx screws which I could field strip in less than 20 minutes), I remember with great nostalgia the times when computer hardware could be replaced on the chip-to-chip level, and voltmeters were as common as software tools like TechTool in checking the health and stability of one’s computer. Additionally, the lack of sites like iFixIt meant that I was learning the complex architecture of the computers in a truly DIY fashion.

I don’t miss the shocks, (though that only seemed to happen when I was working on PCs), but I do miss the hands-on experience I had while working on computers—especially Macs—as a kid. In today’s environment, software hacking seems to be the most enlightening form of computer learning, but it was not always so.

Since donating my IIci to a local school (I installed Netscape Navigator 2.0 so they could use it to access the Internet), I’ve owned a variety of desktop and laptop Macs, but I’ve never been taken in as much by any other Mac’s overall hardware design, even when I first held the impossibly-thin MacBook Air I’m using today.

The monitor might be the most important part of your Mac’s setup–after all, you can’t use any computer without one. Because you’ll spend a lot of time looking at it, you’ll want to invest wisely. Not only will you want a monitor that provides a pleasing experience, but the quality of the images on the screen can also affect your work.

Apple sells displays for its Macs, and you could go with its offerings, but its displays are a quite bit more expensive than what third parties have. Buying from a different company may mean you may not get a feature that Apple offers, but then it may also be a feature that you don’t need, depending on how you use the monitor. Note there are compatibility issues for M1 Macs. We have a guide to monitors for M1 Macs and what you need to know before buying.

Fortunately, there are plenty of companies that have great monitors that you can use with your Mac, without having to take out a second mortgage. Our sister publications TechAdvisor and PCWorld have tested several displays, and we list their top-rated ones that we have been able to confirm work with Macs, alongside the monitors we have reviewed below. Here are our recommendations in alphabetical order.

Apple’s highly specced Pro Display XDR is a stunning piece of engineering, and we found it hard to find fault with the picture quality and colour output, but at that price and with these features this is a display for a very specific audience.

The XDR is phenomenally well-specced: it’s 32in and 6K, offering 40 percent more screen space than Apple’s 5K displays, and offers a peak brightness of 1,600 nits (or 1,000 sustained). But it comes with a seriously eye-watering price tag, especially if you want to include the Pro Stand for adjustability and pivoting.

Picture quality is maintained at ultrawide viewing angles, thanks to industry-leading polariser technology. This is so that a creative team can gather round a single monitor and evaluate a photo, video or design project without suffering a loss of consistency.

As a production display, the Studio Display is still expensive but is an affordable alternative to the Pro Display XDR. Buyers will enjoy its handsome design, good image quality, and impressive spatial audio, but you can save a lot of money by going with a non-Apple display.

The Alogic Clarity is a stunning looking 27-inch display with built-in hub and a fantastic height-adjustable, tilt and pivot stand. It will appeal to Mac users with its Apple looks and is even, in some ways, a superior monitor to Apple’s own Studio Display, although its 4K resolution isn’t as sharp as Apple’s 5K screen.

The sylish Dell Ultrasharp U2421E is a slick design perfect for those with a USB-C/Thunderbolt charged MacBook, as the docking station features are handy. The colour range is also good, and while the price is high for this resolution and size, there are cheaper prices available online—check the latest prices above.

it looks professional and almost Apple-ish, and the support arm allows it to pivot and tilt extensively. It’s also got decent colour representation with close to 100% sRGB coverage and 83% of the P3 colour space.

It’s not a great-looking monitor, with larger than average display bevels on the plasticky chassis. It’s not luxurious but it’s fine for an office or workstation.

Acer’s Nitro XV272 costs more than a lot of 1080p monitors, but the IPS, 165Hz screen provides above-average image quality, excellent color accuracy and motion performance, and a full range of monitor-stand adjustments and a generous array of ports make it worth the cost.

It also has three video inputs, four USB ports, and a stand that feels a bit cheap but offers numerous ergonomic adjustments. These features signal that the Nitro XV272, though not expensive, is a cut above entry-level 1080p monitors.

But there’s more to the U3223QE than the panel. It’s also a fantastic business, productivity, and professional monitor loaded with image-quality options and a king’s buffet of connectivity.

The USB-C hub is crammed to the gills with connectivity. This includes multiple USB-C ports, one of which can handle up to 90 watts of Power Delivery, five USB-A ports, and ethernet.

Gigabyte’s M27Q X doesn’t look like much out of the box, but this 1440p/240Hz IPS panel delivers a superb media experience where it counts, with excellent motion clarity and stunning image quality for an HD screen.

It delivers bright, vivid image quality, but while it includes a USB-C upstream port, the power delivery is a mere 18W, which is nowhere near enough to charge a laptop, so you’ll still need to charge your MacBook with a charging cable or Mac docking station.

Display technology is a bit of a movable feast, with a lot of confusing jargon and technical features to wade through, as well as a variety of different interfaces and cables that are used by Apple itself and the various monitor manufacturers. So it’s worth taking a closer look at some of the factors that you need to think about when buying a monitor for your Mac.

If you’re looking for a size to start with for your own personal research, we recommend 24 inches—just like with Apple’s iMac. That seems like a good size for most people, and it’s easy to go up or down from that point. Most people tend to go between 24 and 27 inches for home use.

Screen resolution can go hand-in-hand with screen size. Screen resolution refers to the number of pixels used to create what you see on the screen. The higher the resolution, the more detail you can see. Larger displays tend to have more resolution options, as well as the ability to support higher resolutions.

Often, when you find two displays that are the same size but have a wide price difference, it’s mostly because of the screen resolution. Monitors with high resolutions are more expensive. For example, Apple’s $1,599 Studio Display is 27 inches, and it has a high screen resolution of 5120×2880 (5K resolution). On the other hand, LG sells the 27-inch 27UK650-W, but it’s a 3840×2160 (4K) resolution display for content creators, and it’s $350–lower resolution, but $1,249 cheaper. (There actually aren’t other 27-inch 5K monitors available, except for the $1,449 LG UltraFine 27MD5KL-B.)

How a monitor connects to a Mac can be confusing. The traditional HDMI and DisplayPort connectors used by many monitors are being replaced–or complemented–by USB-C and Thunderbolt ports. And though USB-C and Thunderbolt cables may look the same, there are actually some important technical differences between them, so it’s important to check which ports your new monitor uses and make sure you buy the correct cables and adapters.

Most recent Mac models have Thunderbolt ports, so if you buy a monitor that has HDMI or DisplayPort interfaces only, then you’ll need an adapter to connect to the Mac. This can get a bit confusing, but Apple does provide a list of the ports included on most recent Mac models so that you can figure out what you need.

Apple also provides a guide to HDMI and DisplayPort technology, which covers Mac models going right back to 2008, so that should provide all the info you need for all the Macs you use at home or at work. Less expensive monitors still tend to use HDMI and DisplayPort, and while it’s not too costly to buy adapters that will allow you to connect your Mac, we reckon it’s worth future-proofing your new monitor by getting one that includes at least one USB-C or Thunderbolt port.

If a display uses Thunderbolt to connect to the Mac, it may have additional USB-C or Thunderbolt ports so the display can act as a hub. In this case, If you have a device you want to connect to your Mac, you can connect it to one of the ports on the monitor, which is already connected to the Mac and probably in an easier location for access.

Look for a USB-C or Thunderbolt connection with power delivery (PD) that can charge your MacBook. A 65W PD will be enough for a MacBook Air or 14-inch MacBook Pro, but you’ll need at least 90W for a 15-inch or 16-inch Pro.

Read our article on how to connect a second screen to a Mac which explains everything you need to know about how to identify which ports you have, the adapters you will require, and how to set things up.

The Macintosh II is a personal computer designed, manufactured, and sold by Apple Computer from March 1987 to January 1990. Based on the Motorola 68020 32-bit CPU, it is the first Macintosh supporting color graphics. When introduced, a basic system with monitor and 20 MB hard drive cost US$5,498 (equivalent to $13,110 in 2021). With a 13-inch color monitor and 8-bit display card the price was around US$7,145 (equivalent to $17,040 in 2021).workstations from Silicon Graphics, Sun Microsystems, and Hewlett-Packard.

The Macintosh II was the first computer in the Macintosh line without a built-in display; a monitor rested on top of the case like the IBM Personal Computer and Amiga 1000. It was designed by hardware engineers Michael Dhuey (computer) and Brian Berkeley (monitor) and industrial designer Hartmut Esslinger (case).

Eighteen months after its introduction, the Macintosh II was updated with a more powerful CPU and sold as the Macintosh IIx. In early 1989, the more compact Macintosh IIcx was introduced at a price similar to the original Macintosh II, and by the beginning of 1990 sales stopped altogether. Motherboard upgrades to turn a Macintosh II into a IIx or Macintosh IIfx were offered by Apple.

Two common criticisms of the Macintosh from its introduction in 1984 were the closed architecture and lack of color; rumors of a color Macintosh began almost immediately.

The Macintosh II project was begun by Dhuey and Berkeley during 1985 without the knowledge of Apple co-founder and Macintosh division head Steve Jobs, who opposed expansion slots and color, on the basis that the former complicated the user experience and the latter did not conform to WYSIWYG—color printers were not common.

Initially referred to as "Little Big Mac", the Macintosh II was codenamed "Milwaukee" after Dhuey"s hometown, and later went through a series of new names. After Jobs was fired from Apple in September 1985, the project could proceed openly.

The Macintosh II was introduced at the AppleWorld 1987 conference in Los Angeles,IBM PC compatibles of the time. Previous Macintosh computers use an all-in-one design with a built-in black-and-white CRT.

The Macintosh II has drive bays for an internal hard disk (originally 40 MB or 80 MB) and an optional second floppy disk drive. It, along with the Macintosh SE, was the first Macintosh to use the Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) introduced with the Apple IIGS for keyboard and mouse interface.

The primary improvement in the Macintosh II was Color QuickDraw in ROM, a color version of the graphics routines. Color QuickDraw can handle any display size, up to 8-bit color depth, and multiple monitors. Because Color QuickDraw is included in the Macintosh II"s ROM and relies on 68020 instructions, earlier systems could not be upgraded to display color.

In September 1988, shortly before the introduction of the Macintosh IIx, Apple increased the list price of the Macintosh II by roughly 20%.AnimEigo notably used the Macintosh II for subtitling their earliest releases, including

CPU: The Macintosh II is built around the Motorola 68020 processor operating at 16 MHz, teamed with a Motorola 68881 floating point unit. The machine shipped with a socket for an optional Motorola 68851 MMU, but an "Apple HMMU Chip" (VLSI VI475 chip) was installed by default and could not implement virtual memory (instead, it translated 24-bit addresses to 32-bit addresses for the Mac OS, which would not be 32-bit clean until System 7).

The original Macintosh II did not have a PMMU by default. It relied on the memory controller hardware to map the installed memory into a contiguous address space. This hardware had the restriction that the address space dedicated to bank A must be larger than those of bank B. Though this memory controller was designed to support up to 16 MB 30-pin SIMMs for up to 128 MB of RAM, the original Macintosh II ROMs had problems limiting the amount of RAM that can be installed to 8 MB. The Macintosh IIx ROMs that also shipped with the FDHD upgrade fixed this problem, though still do not have a 32-bit Memory Manager and cannot boot into 32-bit addressing mode under Mac OS (without the assistance of MODE32).MODE32 contained a workaround that allowed larger SIMMs to be put in Bank B with the PMMU installed. In this case, the ROMs at boot think that the computer has 8 MB or less of RAM. MODE32 then reprograms the memory controller to dedicate more address space to Bank A, allowing access to the additional memory in Bank B. Since this makes the physical address space discontiguous, the PMMU is then used to remap the address space into a contiguous block.

Graphics: The Macintosh II includes a graphics card that supports a true-color 16.7 million color paletteVRAM was 256 KB. The 8-bit model supports 256-color video on a 640×480 display, which means that VRAM was 512 KB in size. With an optional RAM upgrade (requiring 120 ns DIP chips), the 4-bit version supports 640×480 in 8-bit color.

Expansion: Six NuBus slots were available for expansion (at least one of which had to be used for a graphics card, as the Mac II had no onboard graphics chipset and the OS didn"t support headless booting). It is possible to connect as many as six displays to a Macintosh II by filling all of the NuBus slots with graphics cards. Another option for expansion included the Mac286, which included an Intel 80286 chip and could be used for MS-DOS compatibility.

The original ROMs in the Macintosh II contained a bug that prevented the system from recognizing more than one megabyte of memory address space on a Nubus card. Every Macintosh II manufactured until approximately November 1987 had this defect. This happened because Slot Manager was not 32-bit clean.

Accessories: The Macintosh II and Macintosh SE were the first Apple computers since the Apple I to be sold without a keyboard. Instead the customer was offered the choice of the new ADB Apple Keyboard or the Apple Extended Keyboard as a separate purchase. Dealers could bundle a third-party keyboard or attempt to upsell a customer to the more expensive (and higher-profit) Extended Keyboard.

The Macintosh II was offered in three configurations. All systems included a mouse and a single 800 KB 3.5-inch floppy disk drive; a Motorola 68851 PMMU was available as an option and required for running A/UX.

Edwards, Benj (June 7, 2012). "The Macintosh II celebrates its 25th anniversary". Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

"Apple Begins Shipments Of Macintosh II Computer". Wall Street Journal. May 8, 1987. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

John Cook; Carol Cochrane (September 19, 1988). "Apple Announces 68030 Macintosh IIx With High Density Compatible Drive". Business Wire. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

Magid, Lawrence J. (March 2, 1987). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019. ...the color is spectacular. Unlike most color monitors, it also displays very readable text.

the front or back which you press to start and shut down the Mac. Tell us the model of your Mac and we"ll probably know what to offer. Note: if your Mac does not power up, make sure your AC cord is OK and that you have AC power

without replacing parts. If we have them with better parts at a higher price, we"ll advise when you order. We don"t always have these available or ready-to-sell; we"ll of course test and verify before any final quote. They are all "as available" or as described.

I have some UNUSED sealed-box Apple power supplies at MUCH higher costs but I cannot test without opening the box. Check my unused parts list for specifics.

PowerMac 7100, Centris 650, IIvx, IIiv power supplies: 614-0009, Astec 16870. Higher current than IIci, IIcx power supply. $69 each. shipping weight 5 pounds

This is what the 1/2 AA sized battery often looks like in your Mac. Most but the very oldest Macs use what is called a "1/2 AA" battery (see below for other Mac batteries). It"s shorter than an AA battery, but with a voltage of 3.6 volts. If the voltage drops below about 3.2 volts, it"s getting old: often they will read ZERO volts when they stop working. You can use a voltmeter to measure the voltage; if you remove it from your Mac you may have to "reset your PRAM" afterward, and the date and time. Mac "PRAM" memory also stores a few user settings. For a few vintage Macs, they apparently won"t start up without a working battery (but most models do).

For most Macs, there is also a battery cover which holds the battery in place. it"s a plastic frame surrounding the battery which snaps out. Apple number 520-0344. It might break from age when you remove the battery. It"s not essential but if you want one, it"s $3 plus shipping.

Mac PRAM battery, 3.6V 1/2AA, most Macs. Part numbers TL-5101S TL-5101/S 742-0011 922-1262. Battery manufacturers have their own brand and part numbers. Due to postal regulations and the fact you can buy these "on the Web", we no longer stock these batteries. We have a few old-stock batteries we can ship as installed in equipment only. Ask for for availability and price. Do NOT store your Mac with battery in place, it will CORRODE and LEAK!

Mac PRAM battery for Mac Plus, 128K, 512K - 4.5 V AA 4.5 Volt, AA sized. Brands include Panasonic PX 21, Eveready 523, ANSI 1306AP, IEC 5LR50, NEDA 1306AP, Varta V21PX. Look for suppliers of these on the Web, and compare prices. For instance, here"s one brand/model: Dantona� 4.5V/600mAh Alkaline Photo Battery, Model: TR133A. Any model that provides the correct voltage and is the correct size is adequate. Do NOT store your Mac with battery in place, it will CORRODE and LEAK! We may have old-stock, for sale in equipment only, ask.

An alternative to the 4.5V AA battery may be a 3.6V AA-size Lithium battery which is a little easier to find. We may have old-stock, for sale in equipment only, ask. Do NOT store your Mac with this battery in place, it will CORRODE and LEAK!

Mac PRAM battery, square Some Mac systems use a square or rectangular 4.5V battery, with a short black and red cable which connects it to the motherboard. We don"t stock this at this time; check with local computer stores, office supply stores, or electronic parts stores, and take it along so they can determine if they have a compatible battery.Do NOT store your Mac with battery in place, it will CORRODE and LEAK!

CRT (picture tube) for Compact Macs, including yoke (the coils around the neck of the CRT). YOur analog card may need some slight adjustment to orient or size the screen display: we don"t provide "how-to install" descriptions. Prices listed below are for working used CRT"s with yokes, with no to very slight screen burn. Shipping weight per CRT will be near 6 pounds, double boxed to protect them; and boxed under 12 X 12 X 12 inches *if possible* to reduce shipping cost. Typical weight under 6 pounds packed.

Clinton vs Samsung CRTs: I came across this comment about old compact Mac CRT"s: "The Clinton [brand] CRTs have nothing wrong with them but they have no anti-glare coating, which makes staring at them in a bright area an eye-straining experience. The Samsung [brand] units, on the other hand, are anti-glare.". I will charge more if you request a Samsung CRT for older compact Macs which may not have come with them.

We don"t offer CRT"s or picture tubes for the large "all in one" Macs, or for any Apple monitors. Too much work and risk and cost of shipping. Get one local to you and pick it up.

On the compact Macs (128K 512K Plus SE SE/30 Classic), there"s a small video card or cable at the end of the CRT. That carries the "video" into the CRT. We have these, as used pulls, for all those Macs. For instance, the Mac SE and SE/30 uses board with part-numbers 630-0169 and 820-0207; 630-0146 and 820-0205; Apple replacement part numbers are 982-0024. ON the 128K 512K Plus, it"s just a socket on a cable. If you want one of these, please describe your Mac model and describe the part by part-number. I"ll see what I can provide. I don"t get many requests for these.

Shields or shrouds are cardboard, plastic and metal sheets under or around logic boards motherboards or power supplies / analog cards. They look like these or look like these, from some classic Macs. I have a number of these as used, in various conditions and quantities. Ask for one for a specific Mac model, they may vary.

As of 2022, I"m rarely selling Mac cases for the 128K, 512K, Plus, SE, SE/30, Classic, Classic II. Simply put: too expensive to ship, too hard to pack against damage, too much work to photograph and grade, too cheep to buy elsewhere. "Why pay you $X for a case, when I can spend $X plus something and

I"ve generally found, I can"t provide a "compact Mac" case or other small Mac cases, at a price many customers hope for. Some seem to think, I have these "laying around" and I can toss them in a box and mail "em with some air-bag packing. No. Doesn"t work that way. Here"s some guidance about what it really takes to provide a compact Mac case - if you don"t want it busted up.

About shipping: A Mac SE case, with metal frame, nothing else - weighs just over 7 pounds. That case, will need a box 17 X 14 X 14 inches, to ship with enough padding around it to protect the case. A box and padding - let"s say it adds 4 pounds to the package. I should double-box the SE because of safety and because of the large hole where the CRT was removed. Other classic Mac cases may weigh a little less. A CRT adds pounds and is more fragile. Go to usps.com with weight and box size, your ZIP code and

Another complication: Many Mac models have very very fragile plastics. After 30, 40 years, the plastics lose flexibility and will shatter or snap off pieces with any stress. Some models

For PowerMac 7200, 7300, 7500, 7600, 8500, 8600, 9500, 9600, G3 Desktop, G3 Minitower, G3, G4 PCI2IDE AdapterConnect a large hard disk (5GB to 40GB) to your PCI-based Mac for as low as $15 per GigabytePricing starts at $199. Video & Memory Enhancements

Apple PowerPC 4400, 5400, 5500, 6360, 6400, 6500, Starmax, Umax C500, C600 or J710 PowerPC Cache CardsIncrease the performance of your PowerMac or PowerPC-based clone with a 512KB Level-2 Cache card. Verified performance increase on 6400 model of up to 165%. WOW!Affordably priced at $89.

For Power Mac 6100, 7100, 8100 PowerPC Cache CardsIncrease the performance of your Power Mac 6100, 7100 or 8100 with a 256KB or 1MB Level 2 Cache card.Pricing starts at $39.

For Mac IIci, IIvx, IIvi Mac IIci 32KB Cache CardGive your Mac IIci an added boost with a 32KB Cache card. Installs easily into the PDS slot.Priced to sell at $29.

For all Macs MicroMac Technology has Memory for all Mac computers. Call for up to date pricing.Competitively priced.

Cupertino, California Apple today introduced Mac Studio and Studio Display, an entirely new Mac desktop and display designed to give users everything they need to build the studio of their dreams. A breakthrough in personal computing, Mac Studio is powered by M1 Max and the new M1 Ultra, the world’s most powerful chip for a personal computer. It is the first computer to deliver an unprecedented level of performance, an extensive array of connectivity, and completely new capabilities in an unbelievably compact design that sits within arm’s reach on the desk. With Mac Studio, users can do things that are not possible on any other desktop, such as rendering massive 3D environments and playing back 18 streams of ProRes video.1 Studio Display, the perfect complement to Mac Studio, also pairs beautifully with any Mac. It features an expansive 27-inch 5K Retina display, a 12MP Ultra Wide camera with Center Stage, and a high-fidelity six-speaker sound system with spatial audio. Together, Mac Studio and Studio Display transform any workspace into a creative powerhouse. They join Apple’s strongest, most powerful Mac lineup ever, and are available to order today, arriving to customers beginning Friday, March 18.

“We couldn’t be more excited to introduce an entirely new Mac desktop and display with Mac Studio and Studio Display,” said Greg Joswiak, Apple’s senior vice president of Worldwide Marketing. “Mac Studio ushers in a new era for the desktop with unbelievable performance powered by M1 Max and M1 Ultra, an array of connectivity, and a compact design that puts everything users need within easy reach. And Studio Display — with its stunning 5K Retina screen, along with the best combination of camera and audio ever in a desktop display — is in a class of its own.”

Mac Studio delivers even more capability to users who are looking to push the limits of their creativity — with breakthrough performance, a wide range of connectivity for peripherals, and a modular system to create the perfect setup.

With the power and efficiency of Apple silicon, Mac Studio completely reimagines what a high-performance desktop looks like. Every element inside Mac Studio was designed to optimize the performance of M1 Max and M1 Ultra, producing an unprecedented amount of power and capability in a form factor that can live right on a desk.

Built from a single aluminum extrusionwith a square footprint of just 7.7 inches and a height of only 3.7 inches, Mac Studio takes up very little space and fits perfectly under most displays. Mac Studio also features an innovative thermal design that enables an extraordinary amount of performance. The unique system of double-sided blowers, precisely placed airflow channels, and over 4,000 perforations on the back and bottom of the enclosure guide air through the internal components and help cool the high-performance chips. And because of the efficiency of Apple silicon, Mac Studio remains incredibly quiet, even under the heaviest workloads.

Powered by either M1 Max or M1 Ultra, Mac Studio delivers extraordinary CPU and GPU performance, more unified memory than any other Mac, and new capabilities that no other desktop can achieve. With M1 Max, users can take their creative workflows to new levels, and for those requiring even more computing power, M1 Ultra is the next giant leap for Apple silicon, delivering breathtaking performance to Mac Studio. M1 Ultra builds on M1 Max and features the all-new UltraFusion architecture that interconnects the die of two M1 Max chips, creating a system on a chip (SoC) with unprecedented levels of performance and capabilities, and consisting of 114 billion transistors, the most ever in a personal computer chip.

With its ultra-powerful media engine, Mac Studio with M1 Ultra can play back 18 streams of 8K ProRes 422 video, which no other computer in the world can do. Mac Studio also shatters the limits of graphics memory on a desktop, featuring up to 64GB of unified memory on systems with M1 Max and up to 128GB of unified memory on systems with M1 Ultra. Since the most powerful workstation graphics card available today only offers 48GB of video memory, having this massive amount of memory is game changing for pro workloads. And the SSD in Mac Studio delivers up to 7.4GB/s of performance and a capacity of up to 8TB, allowing users to work on massive projects with incredible speed and performance.4

The compact design of Mac Studio puts an extensive array of essential connectivity within easy reach. On the back, Mac Studio includes four Thunderbolt 4 ports to connect displays and high-performance devices, a 10Gb Ethernet port, two USB-A ports, an HDMI port, and a pro audio jack for high-impedance headphones or external amplified speakers. Wi-Fi 6 and Bluetooth 5.0 are built in as well.

And because users frequently connect and disconnect devices, like portable storage, Mac Studio includes ports on the front for more convenient access. There are two USB-C ports, which on M1 Max supports 10Gb/s USB 3, and on M1 Ultra supports 40Gb/s Thunderbolt 4. There is also an SD card slot on the front to easily import photos and video. And Mac Studio provides extensive display support — up to four Pro Display XDRs, plus a 4K TV — driving nearly 90 million pixels.

The all-new Studio Display perfectly complements Mac Studio and also beautifully pairs with any Mac. In a class of its own, it features a gorgeous 27-inch 5K Retina screen, plus sensational camera and audio, delivering that integrated experience Mac users love.

Studio Display brings a stunning all-screen design with narrow borders and a refined, all-aluminum enclosure that houses an advanced set of features in a slim profile. Its built-in stand allows the user to tilt the display up to 30 degrees. To meet the needs of a variety of workspaces, Studio Display also offers a tilt- and height-adjustable stand option with a counterbalancing arm that makes the display feel weightless as it is adjusted. A VESA mount adapter option is also available, and supports landscape or portrait orientation for even more flexibility.

Studio Display features a 27-inch 5K Retina screen with over 14.7 million pixels. With 600 nits of brightness, P3 wide color, and support for over one bill

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey