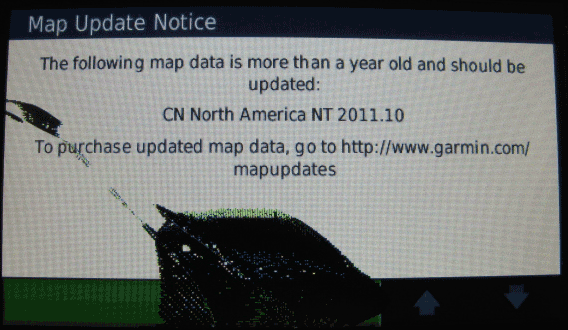

lcd panel looks like it has a smudge free sample

Dirty Screen Effect is a term and acronym often tossed around by TV reviewers and A/V forum enthusiasts as if everyone knows what it is. And, yet, very few folks have ever heard of it before. You may have seen it, though. In fact, if you’ve recently purchased a TV and it doesn’t look quite right, your TV might be suffering from Dirty Screen Effect, more commonly referred to as DSE.

In some ways, Dirty Screen Effect is an appropriate term — and it’s one of those things you just can’t unsee. But it doesn’t exactly look the way it sounds like it should look.

In this quick guide we’ll cover what Dirty Screen Effect looks like, what’s happening on a technical level, and what, if anything, you can do to get rid of it. We’ll also touch on the notion of the so-called “panel lottery” and how that plays into how clean — or dirty — your new TV screen might look.

Dirty Screen Effect (DSE) is a term that’s used to describe an LCD panel that has inconsistent luminance performance across its surface area. It can appear as random splotches, uniform lines, wide bars, and, in some cases, vignetting (a slight darkening toward the corners). DSE once plagued plasma TV panels as well. But since those are no longer in production, we’ll keep this explainer focused on LCD-based TVs.

As a reminder, any TV that uses an LED backlight also uses an LCD panel, so TVs marketed as LED, QLED, and mini-LED are all susceptible. Due to what causes DSE on a technical level, some may argue it can only apply to LCD-based TVs. However, similar effects can be seen in OLED-based displays — thus the term is often applied — so we’ll include those types of TVs as well, but address them separately.

While DSE can be seen in any number of scenarios, you are most likely to see it when there are big swatches of the same color on the screen. Take an ice hockey game, for example. Some areas of the ice will appear to be dingier or darker than other areas of the ice. You might also see DSE more easily when watching golf; when there are vast sections of grass on the screen, some parts of the grass may appear to be darker or more muted in color than other parts.

The trick with DSE is that the issue is fixed to the screen, so as the picture moves, you’ll notice that any part of the picture moving through these “dirty” areas gets a little dimmer. Hence, it seems as if the screen is dirty.

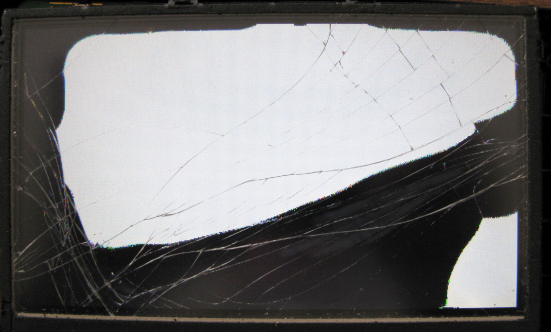

Some DSE is severe and some is so faint you may not notice it unless you look hard for it. As a very clear example of what DSE looks like when exposed by testing slides, we’ve included an example below.

There are a number of factors stemming from the manufacturing of an LCD panel that can cause Dirty Screen Effect, from variance in backlight distribution to variance in TFT switching for sub-pixels, to variance in conductivity and/or capacitance of transparent electrodes. That’s super-nerdy, though, and the actual cause is less important than the common theme here: inconsistency.

In panel manufacturing, there are numerous variables that can be introduced that would cause an LCD panel to have groups of pixels that shine less bright than others. This variance is, unfortunately, part of the tech that makes our TVs. And the manner in which different manufacturers handle that variance is also … you guessed it: Varied.

Dirty Screen Effect also can be caused by damage to the panel in shipping or mishandling of the TV during the setup or installation process. Generally speaking, it’s recommended one avoids “pinching” or otherwise exerting pressure on the front of the TV screen.

This is a difficult question to answer because I do not have data that supports objective analysis on the prevalence of DSE in newly manufactured televisions. However, I can offer some anecdotal perspective based on my experience as a TV reviewer and the feedback I get from readers and viewers, as well as reports I see in A/V forums.

From what I’ve seen, DSE — ranging from insignificant to severe — seems fairly common among newly manufactured LCD-based televisions, due primarily to the nature of LCD panel manufacturing. Very broadly, the less expensive a TV is, the more likely it is to exhibit some level of DSE. More expensive TVs are not immune to the issue, but some manufacturers have tighter quality assurance tolerances for their high-end products so — again, very broadly speaking — DSE tends to be less prevalent among those models.

DSE as a symptom of age is virtually impossible to track, however — again, anecdotally — I have witnessed DSE creep into a TV’s display panel slowly over time and worsen with age. I’ve seen it happen in TVs I own, TVs friends and family have owned, and TVs installed in commercial environments such as hotels and bars.

First, a warning: Once you see DSE on your TV, it’s tough to “un-see.” So, if you are happy with your TV’s performance and wish to stay that way, then you may wish to subscribe to the “ignorance is bliss” theory and forego the following tests.

If, however, you suspect that your new TV may have levels of DSE that you deem to be unacceptable, you can use this YouTube video (also posted at the top of this article) to look for signs of DSE. In our video, we not only provide testing slides that help to expose DSE, but guide you on how to spot it.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to eliminate DSE. Some websites suggest loosening the screws on the back of a TV to lessen the strain on the panel. We do not recommend this tactic as it could stand to void an active warranty. Also, it’s not very likely to work.

Really, the best way to get rid of DSE on a newly purchased TV is to catch it early and return or exchange the TV within the typical 30-day customer satisfaction period. It is rare for a manufacturer’s warranty to cover a repair or replacement when the complaint is over a flaw that the said manufacturer has already deemed to be within an acceptable margin of error.

Most TVs offer a “game mode” which, due to its tendency to brighten everything on-screen, can help to obscure DSE. But this is really just a Band-Aid measure. The DSE is still there, but it may be less obvious. Another somewhat helpful tip to reduce the appearance of DSE in LCD panels is to view the TV from as direct an angle as possible. As you move off-axis (view a TV from an angle) DSE tends to become more obvious.

In very limited instances, some cases of DSE on OLED TVs can be remedied by manually triggering the TV’s built-in “pixel refresh” system, usually located somewhere in the TV’s system menu.

The so-called “panel lottery” refers to the game TV buyers unwittingly play when purchasing a TV. Sometimes you “win the panel lottery,” which is a way of saying that the TV you got was in especially pristine shape and shows no signs of DSE. It’s also a term used to easily express that there’s such a variance in panel quality that it’s virtually impossible you’ll win a perfect panel. In other words, it’s all up to chance.

Many Apple products use liquid crystal displays (LCD). LCD technology uses rows and columns of addressable points (pixels) that render text and images on the screen. Each pixel has three separate subpixels—red, green and blue—that allow an image to render in full color. Each subpixel has a corresponding transistor responsible for turning that subpixel on and off.

Depending on the display size, there can be thousands or millions of subpixels on the LCD panel. For example, the LCD panel used in the iMac (Retina 5K, 27-inch, 2019) has a display resolution of 5120 x 2880, which means there are over 14.7 million pixels. Each pixel is made up of a red, a green, and a blue subpixel, resulting in over 44 million individual picture elements on the 27-inch display. Occasionally, a transistor may not work perfectly, which results in the affected subpixel remaining off (dark) or on (bright). With the millions of subpixels on a display, it is possible to have a low number of such transistors on an LCD. In some cases a small piece of dust or other foreign material may appear to be a pixel anomaly. Apple strives to use the highest quality LCD panels in its products, however pixel anomalies can occur in a small percentage of panels.

In many cases pixel anomalies are caused by a piece of foreign material that is trapped somewhere in the display or on the front surface of the glass panel. Foreign material is typically irregular in shape and is usually most noticeable when viewed against a white background. Foreign material that is on the front surface of the glass panel can be easily removed using a lint free cloth. Foreign material that is trapped within the screen must be removed by an Apple Authorized Service Provider or Apple Retail Store.

If you are concerned about pixel anomalies on your display, take your Apple product in for closer examination at an Apple Store, Apple Authorized Service Provider, or an Independent Repair Provider. There may be a charge for the evaluation. Genuine Apple parts are also available for out-of-warranty repairs through Self Service Repair.*

Have you ever left your TV or monitor on for days, stuck on the same image? You return to your screen, only to find an image burned into the display. No matter what you do, it won"t go away. It is a permanent image burn.

Why do monitors and TVs get image burn? Why can"t manufacturers prevent LCDs and plasma screens from a burnt image imprint? Moreover, what can you do to fix an image burn?

In some cases, you can minimize the image burn effect. In others, you can remove the image burn completely, so long as it hasn"t been burning too long.

Before flat-screens and crystal displays, most TVs and monitors featured CRT (Cathode Ray Tube) technology. In CRTs, individual pixels comprise a red, blue, and green phosphor component. Depending on the intensity of each phosphor component, the pixel appears to the human eye as a unique color.

When a particular still image remains for too long, the intensity of each phosphor component diminishes at an uneven rate. The result is a ghost image on the screen, which is known as image burning.

Plasma displays use plasma, a gaseous substance containing free-flowing ions. When the plasma is not in use, the particles in the plasma are uncharged and display nothing. With the introduction of an electric current, the ions become charged and begin colliding, releasing photons of light.

This is a very simplified version of how a plasma screen works. However, the main thing to understand is that plasma screens use phosphor material (like CRTs) to turn those photons into images.

LCD and LED do not work in the same way as CRTs, either. LCD and LED screens use backlit liquid crystals to display colors. Although manufacturers market screens using LED and LCD, an LED screen is still a type of LCD. The white backlight filters through the liquid crystals, which extract particular colors per pixel.

LCD and LED displays don"t suffer from the same type of image burn as CRTs and plasma screens. They"re not completely clear, though. LCD and LED screens suffer from image persistence. Read on to find out more about image persistence.

Before you can fix screen burn-in, take a second to understand why these images burn in the first place. LCDs and LEDs don"t suffer from burn-in as seriously as plasma screens. But static images can leave an imprint on both display types if left alone for too long. So, why does image burn happen?

First, let"s tackle plasma screen burn-in. Remember why CRTs experience image burn? When a still image remains on the screen for too long, the phosphor components in each pixel wear out at different rates. The uneven burn rates leave behind a ghost image, forever etched into the screen.

Plasma screens also suffer from phosphor deterioration. Plasma burning occurs when pixels on the screen are damaged through long exposure. The phosphor loses its intensity and only shows the light it was fed repeatedly. In this case, the still image, which causes the burn.

LCD and LED screens can also experience image burn, though the image burn process can take longer to develop into a permanent issue. In addition, LCD and LED screens suffer from another issue, known as image retention (also known as image persistence or an LCD shadow).

Image retention is a temporary issue that you are more likely to notice before it becomes a permanent issue. However, proper image burn can still affect LCD, LED, and OLED screens.

Image retention is a different issue from image burn (although it is a precursor to image burn). For example, you"re using an image of a steam train as a reference point for a drawing. You have the steam train image on your screen for a few hours before you decide to play a video game instead.

When you load up the video game on the screen, you can still see the faint outline of the steam train on the screen. The steam train image will remain for a short while, but the movement and color changes of the video game (or film, TV show, or other media type) should erase the retained image.

The other thing to consider is that LED and OLED image burn-in, when it happens, is irreversible. That"s because of how LED and OLED screens work. Individual pixels within an LED display decay when they emit light.

Under normal use, an LED, OLED, or QLED screen won"t suffer image burn. However, if you leave your screen on a single channel for hours every day, then burn-in can become an issue, as it would with almost any screen.

Issues arise when a screen shows a single news channel 24 hours a day, every day, causing channel logos to burn-in, along with the outline of the scrolling news ticker and so on. News channels are a well-known source of television burn-in, no matter the screen type.

Image burn-in fixes exist for LCD and plasma screens. How effective an image burn-in fix is depends on the screen damage. Depending on the length and severity of the image burn, some displays may have permanent damage.

The best fix for screen burn is to prevent it in the first place. Okay, that isn"t super useful if your screen is already experiencing image burn. However, you should always try not to leave your screen on a still image for too long. The time it takes for an image to burn-in varies from screen to screen, between manufacturers, sizes, and panel type.

My personal rule of thumb is to turn off the display if I plan on being away for more than 15 minutes. That way, it is difficult to get caught out, plus you save yourself money on electricity costs and monitor or TV wear and tear.

Another prevention method is to reduce screen contrast as much as you can. Unfortunately, most screens aren"t calibrated correctly, often pushing the contrast and brightness settings too high.

Lower contrast means the lighting across your screen is more even. This means less strain on specific areas of the screen, which helps protect against image burning.

If your plasma or LCD screen already has image burn-in, you can try turning on white static for 12 to 24 hours. The constant moving of white-and-black across your screen in random patterns can help remove the ghost image from your screen.

Unfortunately, this won"t work for extreme cases. Some TVs will have a built-in pattern swiping option that basically accomplishes the same thing (filling your screen with random patterns).

Pixel-shift constantly slightly adjusts the image on your screen, which varies the pixel usage to counteract image burn. You might have to enable a pixel or screen shift option in your screen settings. Pixel-shift is a handy feature for LED and OLED screens that cannot recover from image burn and should help counteract an LCD shadow.

Other modern screens feature built-in screen refresh functions that the manufacturer will advise using to remove image retention and image burn issues.

The best tool for fixing ghost images is JScreenFix. The original program helps fix monitors with dead pixels, but the same company also released an "advanced" version of the tool, known as JScreenFix Deluxe.

While the Deluxe version uses advanced algorithms to repair burned screens and prolong plasma and LCD longevity, the official site is no longer up and running, and there is no way to download the full version officially.

You can find the free version of the Deluxe app online, but it is limited to 20 minutes running at a time. Furthermore, we"re not going to link out to the versions you can find online as we cannot verify the security of these installations. If you do use the Deluxe version, you do so at your own risk.

Another option is to set a completely white desktop background and leaving to run for a few hours. The solid color might reset the image burn. A solid color background is more likely to help with image persistence than image burn, but it is still worth trying.

If you have television burn-in, you can attach a laptop to your TV using an HDMI cable, extend your desktop to the television, and share the white screensaver. Hopefully, that will shift your television burn-in.

The team over at ScreenBurnFixer offers a few different ways you can attempt to fix screen burn on your TV or monitor. As with any other screen burn-in fixes, their chance of working depends on the scale of the issue.

You can head to the ScreenBurnFixer Video page and find a video that matches your screen type, then let the video play for as long as possible (we"re talking multiple hours, not a quick half an hour blast). Alternatively, head to the Chart page and find your device or a device that matches your specifications.

There are several ways you can attempt to fix screen burn-in. The results will vary between the screen type and the level of burn-in. A screen with extensive image burn may not clear entirely, although you might see an improvement.

Some screen degradation over time is understandable. However, if you follow the steps in this guide, you"ll protect your screen from image burn before it becomes a permanent issue.

Use a non abrasive cleaning solution, diluting isopropyl alcohol (not rubbing alcohol, as it may contain oil) into a solution of 50% alcohol and 50% with distilled water water (or purified/bottled water). You could also buy a cleaning solution that does not contain bleach, ammonia, or vinegar.

Before you start, power-off and unplug your monitor. Spray the cleaning solution on a soft cloth (for example an old T-shirt), lint-free microfiber cloth, or some other very soft cloth. A large cloth is best, since it will help reducing the risk of leaving streaks across the display from finger pressure.

Starting from the top, wipe the screen in one direction until you have cleaned the entire screen. Apply light, but distributed pressure. Repeat if necessary. Let it air dry.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Your monitor is made up of millions of pixels. Each pixel is a group of red, green and blue subpixels that combine to create the images you see on your computer screen. When a few are dead or stuck, it can be super distracting.

If you’re having trouble identifying them, though, we’ll show you some tools to use, then tips for ridding your monitor of these tiny little eyesores.

A dead pixel occurs when an entire pixel or a group of subpixels remain dark even when they’re supposed to be on. Since this implies that the pixel or group of subpixels are no longer powering on, they’re harder to fix than stuck pixels. In most cases, dead pixels are lost forever.

A stuck pixel occurs when one or two of the color subpixels remain activated even when they’re supposed to be off. For example, the blue subpixel might get stuck, so the entire pixel will display a different color than what is intended.

To see what’s going on, you can enlist software to help. Try a third-party download like InjuredPixels for Windows. If you’re on a Mac or don’t want to download anything, go with a browser-based solution like LCD DeadPixel Test.

Most monitor manufacturers have a return policy for dead and stuck pixels. They’ll usually replace a monitor if it has more than several pixels stuck in a single color or brightness setting. Since dead pixels are difficult to fix, replacing your monitor via the manufacturer’s warranty is your best route.

You can go the web browser application route with a site called JScreenFix. The free service claims to fix most stuck pixels within 10 minutes by using an HTML5 “PixelFixer” tool.

And since it’s HTML5 and JavaScript-based, there’s nothing to install. All you have to do is bring up the website, drag the PixelFixer window over the stuck pixel area then leave it on for at least 10 minutes.

After detecting your monitor’s stuck or dead pixels, use PixelHealer’s flashing color box on the affected areas to try and jolt the pixels back into shape. The site claims that the tool uses the already proven method of using flashing RGB colors to restore a stuck pixel or even revive a dead one.

If your monitor is out of warranty and none of the pixel fixing software methods are working for you, you have two choices. Either you learn to live with a few stuck or dead pixels here and there, or, if you’re brave enough, there’s a last-ditch method you can attempt.

First, take note of the location of the stuck or dead pixel. Then turn off your monitor and try applying gentle pressure on the affected area to “massage” it back to life. Use something with a narrow but flat edge like a pencil eraser or a pen cap. To avoid damaging your screen, wrap it with a soft, damp microfiber cloth.

The idea is that by applying gentle force, you might coax the pixel back into its proper alignment. If not done correctly, this method can actually create more dead pixels, and extreme caution is required.

If you spend long enough debating the merits of LCD vs. OLED display technologies, eventually, someone will touch upon the subject of the dreaded OLED screen burn in. The point made is that OLED displays will inevitably suffer from horrible-looking artifacts over time, while LCD and new technologies like Mini-LED won’t. But like most of these debates, you’ll probably hear as many overblown anecdotes as you will actual facts about the issue.

You may never have experienced it for yourself, but many consumers are wary about the possibility of burn in when pondering their next smartphone purchase. Particularly as expensive flagship smartphones have universally adopted OLED display technology. Apple, Google, and other manufacturers acknowledge that burn in can be a problem in rare cases. OLED technology has made its way to much more affordable price points in recent years, putting the issue on the radar for even more consumers.

The word “burn in” is a little misleading, as no actual burning or heat problems are involved. Instead, this term describes a display suffering from permanent discoloration across any part of the panel. This may take the form of a text or image outline, fading of colors, or other noticeable patches and patterns on display. The display still works as expected, but a somewhat noticeable ghost image or discoloration persists when the screen is on. To be considered screen burn in, these artifacts have to be permanent and are a defect caused on the display hardware side. Rather than a graphical glitch that may be caused by software, temporary image retention, or a problem with the display driver circuitry.

The term dates back to old CRT monitors, where phosphor compounds that emit light to produce images lost their luminance with time. LCD panels can exhibit similar problems, but these are much rarer due to the nature of LCD’s backlight and color matrix design.

Although not as bad or noticeable as old CRT issues, today’s OLED smartphone displays can eventually suffer from a similar problem. That being said, it’s pretty difficult and rare to notice unless you know what you’re looking for, and it takes hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of screen-on time before any such errors appear. In smartphones, pattern burn in is typically associated with always-on displays, navigation buttons, and the notification bar. The example below demonstrates a textbook case:

Although most smartphones now support gesture navigation controls in the place of the old button design. So this type of burn-in is much less of a problem than it used to be.

The cause of all screen burn in is the varying lifecycle of a display’s light-producing components. As these parts age, their brightness changes, and therefore the panel’s color reproduction gradually shifts with time. Although this can be mitigated somewhat with clever software, all displays experience some color shift as they age. But with burn in, some parts of the screen age faster than others. This can gradually shift the perceivable colors of the screen in one area more than in another, leaving what looks like a ghost image behind.

With modern smartphone and smartwatch technology, screen burn in can manifest due to the different life spans between the red, green, and blue LED subpixels used in OLED panels. As we mentioned before, areas of the display that seldom change, are bright white, or are often black and switched off, such as navigation buttons or the notification bar, are the most likely areas to notice this issue. You may also notice the effect in darkened status bars designed to hide display notches.

This is because these areas are more likely to consistently display one color, a set icon, or text. In contrast, the rest of the display produces a more random selection of colors from various websites, videos, apps, etc., over a long period of use. Therefore the subpixels in these areas see different amounts of use and thus age differently, eventually resulting in a slight variation in color reproduction. Switching to transparent and color-changing bars has the added bonus of evening out the color aging process.

Speaking more technically, the issue is that blue LEDs have significantly lower luminous efficiency than red or green pixels. This means that a blue LED needs to be driven at a higher current for a set sized pixel to achieve the same brightness as red or green. Higher current causes the pixel to degrade faster, shortening its lifespan and eventually tinting the display towards the red and green colors. Therefore an OLED display’s color doesn’t degrade evenly; it will ultimately lean towards a red/green tint.

So, if one part of the panel spends a lot of time displaying a blue or white image, the blue pixels in this area will degrade faster than in other areas. That’s essentially what burn in is. However, display manufacturers do account for this in their panel designs.

If OLED screens have a problem with burn in, why do we continue using them? Burn in is a true downside to OLED displays, but there are plenty of reasons consumers and manufacturers like them. For starters, image quality is much better than in LCDs. OLED panels can reproduce more vibrant colors, more contrast, wider viewing angles, and faster refresh rates. Colors tend to be much more saturated, and blacks are much darker.

OLED displays have a simpler design, allowing thinner, lighter smartphone designs. You can also thank OLED technology for foldable phones and curved displays. If those improvements weren’t enough, you’ll also enjoy lower power consumption with OLED.

Additionally, burn in problems are only common after prolonged periods of use. As you may already know, smartphone manufacturers don’t expect you to keep a smartphone for more than 2-3 years. Recent statistics show that consumers currently keep their phones for an average of 2.75 years.

At this stage, manufacturers are very aware of the potential issues and have already taken some intelligent steps to help avoid burn in. For starters, Samsung has been using its pentile subpixel arrangement in its AMOLED displays since the Galaxy S3. By making the blue subpixel larger, it requires less current to drive in order to provide the necessary light. Driving the LED with less current increases its lifespan, so it takes longer for any noticeable color shift to occur.

This doesn’t directly address the issue of different parts of the screen aging at different rates, but it does mean that it will take significantly longer to notice than with older or cheaper OLED panels. More expensive and modern OLED panels are built with longer-lasting LEDs and well-designed layouts, meaning flagship smartphone displays age slower. These days, it’s cheaper phones packing cheaper displays that are marginally more likely to see issues after heavy use.

There are software solutions too. Android Wear product manufacturers can enable the OS’s “burn protection” option. This mode periodically shifts the screen’s contents by a few pixels, so they spend equal time displaying different colors. Smartphones equipped with Always-On display technology employ a similar tactic. Google also suggests a selection of design guidelines tailored to avoid screen burn-in problems when designing OLED watches. The move towards gesture rather than on-screen navigation controls is also helping to alleviate one of the more noticeable burn in areas.

If your screen is already burnt in, there’s not much that can be done to undo the damage. Some apps on the Play Store claim to reverse the problem. These will end up “burning” the rest of the screen to match the colors, which isn’t a real solution.

Keep your display brightness as low as reasonable. Increased brightness requires more current and therefore shortens LED lifespans. Don’t crank up the brightness unless you have to.

Use Immersive Mode, where available. This hides the notification bar and its static icons. Alternatively, pick a launcher that offers a similar feature, as well as a transparent navigation bar and app drawer options.

Try to make it so that the screen isn’t displaying the same thing all the time, in the same areas of the screen. For example, if you have a widget that almost always looks the same, chances are it will eventually burn into the image. Move things around now and then, and try to keep the view of your phone dynamic.

All that said, screen burn in isn’t something that should concern many users if they’re looking to buy a new OLED smartphone. Modern panels have much longer lifespans than early OLED smartphones, and even then, burn in was rare. Just don’t leave a static image on the screen 24/7 with the brightness set at max.

The bottom line is that you should be looking at several years’ worth of use out of a modern smartphone display before any screen burn in will be noticeable. But it doesn’t hurt to be aware of what can happen to aging handsets and how to maximize their lifespan.

How much DSE you see depends partly on the model you purchased. Pricier models generally feature improved better uniformity, mostly because manufacturers use more rigorous quality standards for their high-end products. But, no matter how much you spend, uniformity is unique to every individual unit, meaning you don"t really know how much DSE you"re getting until you see it in person.

Is your obsessive side getting twitchy yet? Before we discuss upping your Xanax prescription, let"s review how the DSE demon begins its possession of your beloved screen.

If you own a plasma TV, the pixels are individually illuminated and all capable of achieving the same level of brightness. This tends to make DSE less visible in these devices, particularly in high-end models.

Still, DSE may afflict cheaper versions, particularly if the anti-reflective coating on the glass that overlays the screen is of low quality or poorly applied. Furthermore, as the display ages, the phosphors in the screen may begin to wear out or malfunction, all of which can contribute to less uniform images, which is often apparent particular in scenes with fast panning shots.

In LCD and LED TVs, DSE is typically a bigger issue, one that"s due to the way these units are illuminated. Before we proceed, it"s worth mentioning that although marketing-speak often treats LED and LCD TVs as completely different technologies, they"re not different beasts.

LED units could be more accurately described as "LED-backlit LCD televisions," but salespeople and consumers alike are too lazy to utter that tongue-wearying phrase while haggling in a big-box store. What"s important to realize is that both categories rely on LCDs (liquid crystal displays), which act as shutters that either block light or allow it to pass, depending on the image that"s being rendered on the screen.

There are a variety of factors that affect LCD quality, notably illumination source. Older LCD TVs, for example, used multiple cold cathode fluorescent lamps (CCFL) to light LCDs from the rear. They provide generally smooth and even illumination, but they make the final product rather bulky.

More modern TVs rely on LEDs (light-emitting diodes) as a light source. Some models have what"s called full-array backlighting, in which the LEDs are stationed in regular intervals behind the screen, creating even lighting and excellent picture quality.

Other models incorporate what"s called edge lighting, which positions the LEDs along the edges of the screen. In general, the overall picture quality isn"t quite as good as a backlit screen, but manufacturers still use it because it allows them to build substantially slimmer TVs.

Regardless of the lighting source, sometimes it"s not the technology itself that results in DSE. It might be due to the way the display was handled at the factory or even en route to your home.

If you"ve ever pressed a little too hard on your smartphone or computer screen, you"ve likely witnessed a bit of discoloration, clear evidence of how sensitive LCDs are to physical pressure. Now, picture a huge manufacturing facility that cranks out thousands of these units per week. It"s easy to see how a bit of mishandling could alter the screen"s consistency.

The same goes for shipping. Some units travel long distances in cargo boxes, and then take bouncy rides in your car to their final resting place on your living room wall. That"s a lot of opportunities for tiny mishaps to affect LCD uniformity.

In a laboratory at the University of Hull 50 years ago, a new chemical compound was created that would impact the world as much as any drug, fuel or material. The man responsible for this society-changing invention was George Gray – his new liquid crystal molecules (now known as 5CB) made liquid crystal displays (LCDs) viable and kickstarted the multibillion-dollar flat-screen industry.

The story begins back in 1967 when John Stonehouse, a Labour MP and minster for technology under Prime Minister Harold Wilson, established a group to develop a technology that had only just made its debut on Star Trek – a full colour flat-screen display.

Unfortunately for Stonehouse, his amazing foresight has since been overshadowed by his attempt (in 1974) to fake his own death to avoid punishment for multiple counts of fraud and forgery.

Liquid crystals are a state of matter that sits between liquids and solids. They flow like a liquid, while the molecules within them maintain some order relative to each other, like in a crystal. The long and thin molecules pack against one another in an ordered rectangular arrangement of rows.

Crucially, these liquid crystal structures can interact with light in interesting ways, and this is key to how they work within flat-screen displays. Each pixel within an LCD is comprised of a light source, usually a light-emitting diode (LED), and a thin layer of liquid crystals sandwiched between two filters that scientists describe as polarising.

The light emanating from a bulb, LED or the Sun is known as unpolarised, in the sense that it consists of waves travelling outwards in a variety of orientations. By analogy, imagine a group of schoolchildren all waving skipping ropes. Some will wave their ropes up and down and some side to side, and some at angles in between.

Polarising filters bring order to emanating light waves by only allowing waves with a particular orientation to pass. As well as in LCDs, you find them in some sunglasses, for example. If we return to our rope analogy, imagine the ropes are fed through a slatted gate. The parallel slats of the gate only allow the waves travelling up and down to propagate, while the waves from all the children shaking their ropes in other directions are restricted – that’s what polarisation does with light.

Now imagine you have two polarising filters. You place one on top of the other and hold them up to the light. As expected, they cut out some of the light getting to your eye. Now, while keeping one in front of the other, you twist a filter by 90 degrees. It turns out that something odd happens – they now cut out all the light and together the filters appear opaque. In this orientation the first filter is cutting out the “side-to-side” polarised light, whilst the second filter cuts out “up and down” light.

The thin layer of liquid crystals between these polarising filters does something rather clever. The molecules stack in the shape of a helix that twists the polarisation of the light, letting it slip through the second filter.

There’s one more thing needed to turn this sandwich of polarising filters and liquid crystals into a pixel within a display. You need some means to switch the liquid crystal’s light-twisting properties on and off. That way you can control whether a pixel is bright or dark.

And, this is where we return to Stonehouse – because back in 1967 he got the ball rolling to crack that problem. In his role at the Ministry of Technology, Stonehouse soon learnt that the UK was paying the Americans more for the rights to use their colour cathode ray tube technology (in those big bulky televisions and monitors) in displays used by the military than it was spending on developing the supersonic airliner, Concorde.

This convinced him that the UK needed to develop a colour flat-screen panel. A government working group, led by the physicist Professor Cyril Hilsum, met with experts in their respective fields to decide which technologies should receive funding. When it came to the meeting on liquid crystals, the expert was asked why the light was reflecting off his sample bottle of liquid crystals and casting such a curious pattern on the wall. He couldn’t answer – but a young George Gray, a chemistry lecturer from the University of Hull, could. And that moment of brilliance won him the contract.

Within a year, Gray’s research team had developed a liquid crystal that was stable, easy to manufacture and, most importantly, included a positive charge at one end. The charge meant that an electric field could be applied to a pixel, pulling on the charged molecule to break up the structure of the liquid crystals and turn the pixel dark. Removing the power allowed the stack to reform and the pixel to flip back to white.

The molecule is known as 4-Cyano-4’-pentylbiphenyl, or 5CB for short. And by 1974 the first devices containing this compound were on sale, such as calculators and digital watches. Even to this day, if you own a watch with a grey and black display you’ve got some 5CB on your wrist.

Colour screens came a bit later. They work on exactly the same principle, except each pixel is made from three tiny sub-pixels, with red, green and blue filters added to the layers, each of which can be controlled individually to generate the millions of hues we expect in our modern high-resolution screens.

The first colour flat-screen TVs hit the market in 1988 when the Sharp Corporation launched its 14-inch LCD TV. Unfortunately Stonehouse missed seeing his vision come to fruition as he had died earlier that year.

Accidental Damage is any damage due to an unintentional act that is not the direct result of a manufacturing defect or failure. Accidental damage is not covered under the standard warranty of the product. Such damage is often the result of a drop or an impact on the LCD screen or any other part of the product which may render the device non-functional. Such types of damage are only covered under an Accidental Damage service offering which is an optional add-on to the basic warranty of the product. Accidental Damage must not be confused with an occasional dead or stuck pixel on the LCD panel. For more information about dead or stuck pixels, see the Dell Display Pixel Guidelines.

No, accidental damage is covered for Dell computers or monitors which are covered under the Accidental Damage Service offering for that specific product.

For more information about Dell Limited Hardware Warranty and Dell"s Accidental Damage service offering, see the Dell Warranty & Support Services page.

NOTE: Other damages may be considered customer induced if determined by Dell Technical Support, an on-site field engineer, or at the mail-in repair center.

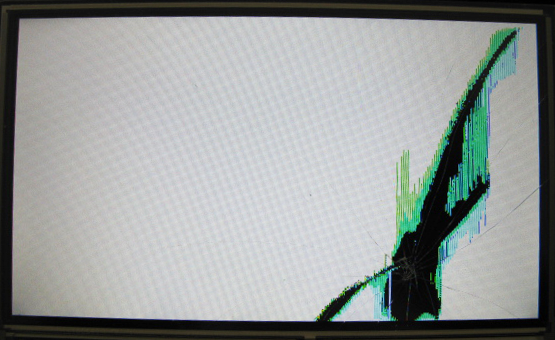

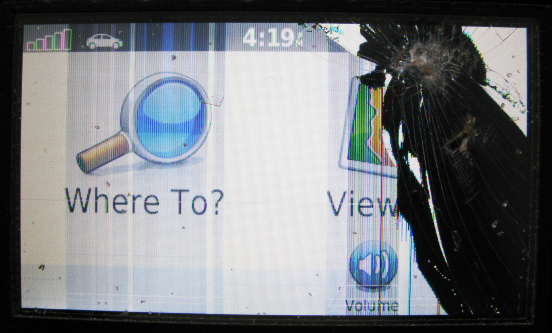

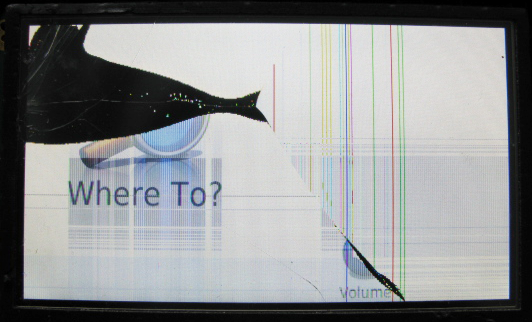

The LCD glass on the display is manufactured to rigorous specifications and standards and will not typically crack or break on its own under normal use. In general, cracked, or broken glass is considered accidental damage and is not covered under the standard warranty.

Internal cracks typically occur due to excessive force on the screen. This can be the result of some object hitting the screen, a drop, attempting to close the lid while an object is on the keypad area, or even holding the laptop by its screen.

Spots typically occur due to an external force hitting the screen causing damage to the LCD panel"s backlight assembly. While the top layer did not crack or break, the underlying area was compressed and damaged causing this effect.

If your Dell laptop LCD panel has any accidental damage but the laptop is not covered by the Accidental Damage service offering, contact Dell Technical Support for repair options.

Dell monitors cannot be repaired by an on-site field engineer or at the mail-in repair center. If you notice any damage to the monitor, you must purchase a new monitor.

Laptop users can strive to make the most of their laptops to maximize stability, longevity, and usability. Understanding and implementing a few best practices for the safe handling of their laptop will enable them to enjoy their laptop for many years to come. For more information, see the Dell knowledge base article Dell Laptop Best Practices for Care, Use, and Handling.

All screens flicker to some degree — be they TV screens, car navigation displays, monitors, tablets, and yes, even smartphone displays. In this article, we will talk a little about what flicker is, what can cause it (on smartphones in particular), and how we at DXOMARK test for it, quantify it, and measure its impact on the end-user experience.

Flicker is a quick oscillation of light output between on and off; it is measured in hertz (Hz) to quantify the frequency at which the oscillation occurs. While we may not be consciously aware of the flicker phenomenon, it’s important to understand that our eyes still physically respond to it — that is, our irises expand and contract in response to these changes in brightness. This involuntary physiological response can certainly explain why we may have a headache and particularly why our eyes can feel tired after looking at a display for an extended period of time — they have been working hard! (This is especially true when looking at a display in dark ambient conditions, such as reading in bed with the lights turned off, for reasons we’ll touch on a bit more below.)

Given the ubiquity of smartphones, it is unfortunate that the flicker on their displays (especially OLED displays) is still an issue for many people. But wait! Why do they flicker? Well, let’s remember that smartphone display hardware is based on either LCD (liquid crystal display) or OLED (organic light-emitting diode) technology. LCDs don’t emit their own light; rather, they are back-illuminated by a strip of LEDs whose light intensity is quite powerful so as to compensate for the brightness drop due to the low transmission rate of the LCD panel (caused mainly by the RGB color filter). By contrast, in an OLED display, every pixel is itself an OLED that produces its own light.

Since both LCDs and OLED smartphone displays are composed of light-emitting diodes, let’s describe how these diodes are driven. Because of a diode’s intrinsic physical properties, it cannot be dimmed by changing the intensity of the current (mA) without impacting the color of the light. So how do phone manufacturers dim displays? They make use of a technique called pulse-width modulation (PWM), which means that they turn the diodes off and on at varying rates. Because we normally should not be able to see this switching between off and on (in other words, the flicker!), our brains are fooled into perceiving the screen as simply dimmer overall (a phenomenon known as the “brain averaging effect”). How dim depends on how long the diodes are off versus how long they are on: the longer they’re off, the dimmer the screen will appear.

So both LCDs and OLED displays power their light sources differently, but both technologies are subject to flicker effect; however, it is usually more noticeable on OLED displays than on LCDs. For one thing, OLED displays and LCDs show PWM at different frequency ranges — the PWM of OLED displays range from ~50 to ~500 Hz, whereas the PWM of LCDs starts at around 1000 Hz or higher. Second, as the human eye may experience flicker sensitivity up to about 250 Hz (at least for most people), it should come as no surprise that OLED displays are more likely to cause eyestrain than LCDs.

An on/off modulation pair is called a period, and the amount of time that the diode is switched on in a period is called a duty cycle. The chart below illustrates how different PWMs affect the perceived brightness of a display:

A significant disadvantage to using PWM technology can be that when a display adjusts to its minimum brightness in very dim or completely dark ambient light conditions, the duty cycle is very short and the interval when the diode is off is proportionately much longer (for example, minimum brightness may translate to a 10% duty cycle, meaning that the diode is off for 90% of the period). At lower PWM frequencies, flicker can become much more noticeable, which helps explain why reading text or watching videos in bed at night is more likely to cause headaches and eyestrain than when viewing screens in brighter conditions.

The video below was shot with a Phantom VEO-E 340L camera at 1500 fps (as were the other videos further below), slowed down to 4 fps to show display pulse-width modulation (PWM) — the white areas separated by black lines that extend across the screen when brightness diminishes at regular intervals. You can see the difference between the Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra 5G on the left, which has a medium duty cycle (around 60%), and the Huawei P40 Pro and the Oppo Find X2 Pro, which have long duty cycles (roughly 90%; the black lines show that the OLEDs are turned off, albeit briefly):

So how does DXOMARK measure flicker? One major way is with a device called, appropriately enough, a flickermeter (specifically, a TRD-200 from Westar Display Technologies), whose sole purpose is to measure quick oscillations in brightness. Our engineers follow a strict protocol for measuring flicker on each smartphone display: all devices are individually tested using their default settings under the exact same dark (< 0.1 lux) ambient lighting conditions, and are placed at the same distance from the flickermeter. We chart the output on this graph (which we use to compare up to four phones in our display reviews; note that you can click on the name of a phone in the legend on the bottom of the graph to remove or redraw its results):

Yes, it’s a cool-looking graph, but what does it mean? How should we read this? Well, first of all, keep in mind that these results correlate with each device’s PWM — the on/off power cycle that helps control screen brightness. The horizontal X axis show the frequency of the oscillations over time measured with the flickermeter in hertz (Hz). The vertical Y axis shows the SPD(dB)— spectral power density in decibels, which is the amount of power associated with one frequency of the signal that the display generates.

The first spike in our flicker graph appears at a phone’s listed refresh rate, but it is the highest spike — that is, the one that comes closest to or surpasses 0 dB — that is of interest to us in terms of flicker, as it indicates the PWM frequency; in this case, 241 Hz for the Samsung (S20), 362 Hz for the Huawei, 481 Hz for the OnePlus, and 240 Hz for the other Samsung (Note20). (Just in passing, you can nearly always ignore values below -40 (dB) on the graph, as they correspond to testing noise.)

The very slow-motion video below imitates the results of a flickermeter test. What is interesting to note is that from left to right, the devices scroll faster, which indicates different PWM frequencies.

In this second very slow-motion video, we included the Samsung Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G that has a refresh rate of 120 Hz; interestingly enough, however, its PWM frequency is 240 Hz (as the flicker graph above also showed). In the video of the Note20 Ultra 5G, you can see that it has one frame on (bright) to five frames off (dark); the P40 Pro ends up with one frame on to three frames off; and the Find X2 Pro varies between one frame on to two or three frames off. All this is to say that where flicker is concerned, even a phone with a fast refresh rate like the Samsung Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G can have a low PWM frequency and thus noticeable flicker under certain conditions. If you are sensitive to flicker, you will likely notice it on the Samsung devices at this brightness level and these PWM frequencies, but not on other devices with higher PWM frequencies.

You will no doubt notice the striking difference between the two Oppo Find X2 Pro devices on the right in the video above. While the Oppo device already benefits from a fast PWM rate, the shot of it on the far right shows the very noticeable effect of the Find X2 Pro’s flicker reduction feature (something we do not test in our current protocol, but that our technical team felt was worth pointing out).

Keep in mind that our engineers base their evaluations and the scores they assign to smartphone displays not only on the objective tests they perform with flickermeters and other instruments, but also on perceptual tests that they conduct after being specially trained to see flicker.

To further illustrate flicker, our engineers used a DSLR mounted on a translation rail and moved it quickly while it took a slow (1/10 second) shot of the three mounted smartphone displays shown below to imitate the effects of PWM. In the image of the Samsung Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G on the left, you can see each individual white dot; on the Huawei P40 Pro in the middle, the individual dots are much closer together, but are still largely discernible; in the image of the OnePlus 8 Pro, however, the dots look more like an almost continuous line. Unsurprisingly, flicker is stronger on the devices where the white dots are further from one another — that is, devices with a lower PWM frequency.

Let’s wrap things up by first repeating that flicker on smartphones is caused by the use of pulse-width modulation that turns light-emitting diodes off and on to control screen brightness levels. As we normally perceive flicker via our peripheral vision rather than via our “attending vision” (that is, what we specifically focus our eyes on), the small size of a smartphone screen makes it less likely that we will see flicker on it (unless we hold the phone very close to our eyes) than we might when viewing content on a laptop screen or monitor. When we do see flicker, however, it’s the PWM that is the culprit; and while flicker can be reduced on a phone with a higher refresh rate, you may sometimes see flicker on it anyway if the phone’s PWM is slow (as we saw with the Samsung Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G).

Finally, it’s also important to remember that some people are more sensitive to noticing flicker than others; in fact, even people who may not consciously perceive flicker may nonetheless be sensitive to it, winding up with headaches or eyestrain after overdoing their screen time. Such people could choose an OLED smartphone with an anti-flicker feature, or one with an LCD. As you can see in the table below, the last entry shows the data for the Xiaomi Mi 10T Pro; since it uses LCD technology, its PWM frequency is so high that it in essence eliminates the flicker issue.

This all said, you can rest assured that if our testers do discover a smartphone that has noticeable problems with flicker at its default settings, we will let you know about it as part of its Display review. (And by the way, we’ll also mention if a smartphone comes with a “flicker-free” feature or setting.)

If you’ve noticed unusual spots on your display, you might be dealing with stuck or dead pixels. Fortunately, these pixels are usually harmless and can be detected using special pixel tests.

Dead and stuck pixels can appear on LCD screens of all kinds. This includes monitors, phones, and camera displays. It’s easier to spot them on larger displays, though.

If you’re using a camera, carefully look at your LCD display as you take photos. Are there any spots that stay in the same place no matter how much you move your camera? Those spots are dead or stuck pixels.

There’s a distinct difference between stuck and dead pixels. If you’re completely sure that the pixels on your screen aren’t dust, you need to identify them.

Stuck pixels are usually red, green, blue, or yellow. Dead pixels are black. No matter how much your screen changes, those pixels will remain fixed in one spot and won’t change their colour.

Keep in mind that stuck pixels can also be black or very dark in colour. You might accidentally mistake them for dead pixels. To make sure that they’re not dead, you need to use a dead pixel test. More on this later.

Stuck pixels are much easier to remove than dead pixels. If you’re sure that there’s a dead pixel on your screen, you’ll probably have to hire a specialist or replace your display.

Here are a few simple websites that let you check for dead pixels using solid colours. They basically do the same thing, but one of them might be more compatible with your device/browser than the other:

You need to be in full-screen mode. Make sure you wipe your screen beforehand so that you don’t accidentally mistake a speck of dust for a dead pixel!

Click on each colour. If you don’t notice any unusual spots (black or any other colour) on your screen, it’s likely that you don’t have an issue with dead or stuck pixels.

Some users recommend rubbing a dead pixel using a cloth to get rid of it. This might work temporarily, but it will damage your display in the long run.

Too much rubbing can damage even more pixels on your screen and lead to serious problems. If none of the solutions work, the best way out is to contact a specialist.

As mentioned previously, dead pixels are usually impossible to remove without professional help. However, you need to make sure that those dead pixels aren’t secretly stuck pixels or simply dust particles.

This is a very simple and seemingly straightforward method, but it might be the best solution to your problem. If your screen appears glitchy, it might simply need to be refreshed.

Use a screen-cleaning spray and a cloth to wipe your display. Make sure you don’t apply too much pressure or else you might damage your screen. A few gentle swipes might get rid of the problem.

If the options above don’t work, JScreenFix might be your best solution. This is a website that anyone can use for free. You don’t need to download any programs or extensions to use it. Best of all, it promises to remove stuck pixels in less than 10 minutes.

What JScreenFix does is fix stuck pixels. If you think you have a dead pixel, you can try this method as well. For this to work effectively, you need to know where exactly your stuck pixels are located.

Your job is to find the stuck pixel and drag the box to it. Leave it there for a few minutes. This should get rid of any unusual pixels on your display.

If you’re sure that the pixel is dead (and not stuck), then you’ll need to see a specialist. There are a few methods for fixing dead pixels, but most of them don’t seem to work effectively.

No. More often than not, stuck pixels are temporary. You might have to try a few methods to remove them. There are a couple of programs that promise to remove stuck pixels quite easily.

Dead pixels usually don’t spread. They’re usually a small fault in a display. If they do spread, you might need to hire a specialist or replace your screen.

Make sure you clean your display, take a dead pixel test, and use JScreenFix to get rid of the pixels. It’s likely that this will fix the problem and prevent you from consulting a specialist.

In the TV world, LG has a page that says "It is rare for an average TV consumer to create an environment that could result in burn-in." Nonetheless, stories of OLED burn-in don"t seem rare online, with owners on YouTube, forums and social media reporting the issue. Reviews site RTings has demonstrated burn-in on LG OLED TVs in long-term tests.

So if the fear of the mere possibility of burn-in is your primary concern, the decision is simple: Buy an LCD-based display instead. But know that you"re sacrificing the best picture quality that money can buy. Here are some points to keep in mind:

All things considered, burn-in shouldn"t be a problem for most people. That"s why we at CNET continue to recommend OLED-based TVs, phones and other devices in our reviews. From all of the evidence we"ve seen, burn-in is typically caused by leaving a single, static image element, like a channel logo, onscreen for a very long time, repeatedly.

If you, like most people, watch a variety of content on your TV, phone, or other device with an OLED screen, you"re not going to need to worry about burn-in.

What can you do to prevent burn-in on that new TV? As we mentioned, vary what you watch a bit. In particular, don"t watch something that has the same static areas displayed onscreen, nonstop for days on end.

The logos and news tickers on cable news channels are examples of those static areas -- they have elements that never move, and they remain on screen the entire time you"re watching. That means if you leave your TV running Fox News, CNN, MSNBC or ESPN all day long and don"t watch enough other programming, you"re more likely to get burn-in. Or at least, image retention, which we"ll discuss in a moment. If you play the same game for 8 hours a day, every day, the onscreen status display or HUD is also a likely culprit for burn-in.

To repeat, you can watch those channels, play games or whatever else to use your TV as a TV, your phone as a phone, etc. You just shouldn"t watch only those channels, all day every day. And if that sounds extreme, know that emails I"ve gotten from readers about burn-in always have some variation on "well I only watched that channel for 5 hours a day." If that sounds like you, get an LCD.

As long as you vary what"s displayed, chances are you"ll never experience burn-in. That varied content will age your screen evenly. So in a 24-hour period you watch a movie, play some games, binge some TV shows, they"re all varied enough that you should be fine.

The RTings torture test we mentioned above lasted the equivalent of 5 years of use and they still say "Our stance remains the same, we don"t expect most people who watch varied content without static areas to experience burn-in issues with an OLED TV."

We"ve designed the OLED screen to aim for longevity as much as possible, but OLED displays can experience image retention if subjected to static visuals over a long period of time. However, users can take preventative measures to preserve the screen [by] utilizing features included in the Nintendo Switch systems by default, such as auto-brightness function to prevent the screen from getting too bright, and the auto-sleep function to go into "auto sleep" mode after short periods of time.

Which is to say, Nintendo is fully aware of this potential and took steps to minimize the risk. Also, despite many games having static HUDs, you"d need to play just that one game, for hours upon hours, every day without ever using the screen for anything else, at the highest brightness settings.

Let"s get the descriptions right. Though often used interchangeably, "image retention" and "burn-in" are not the same thing.Image retention is temporary: It goes away in time.

Image retention occurs when parts of an image temporarily "stick" on the screen after that image is gone. Let"s say for an hour you"re looking at a still picture of a white puppy (hey, you do you, we won"t judge). Then you decide to watch a movie. Let"s say Best in Show because you"re keeping with your theme. But as you"re watching you can still see the white puppy image, as if it"s a ghost on the screen, staring at your soul.

You"re not crazy, probably. That"s just an extreme case of image retention. Chances are it will go away on its own as you watch stuff that isn"t the same still image of the puppy.Here"s a section of a 2018 LG C8 OLED TV screen displaying a gray test pattern after 5 hours watching CNN on the brightest (Vivid) mode. They"re the same image, but we"ve circled the section with the logo on the right to highlight it. To see it better, turn u

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey

Ms.Josey